By Scott Stoppelman

History seems to indicate that the years between wars or major conflicts are often periods of relative inactivity in the development of small arms. In the years immediately prior to what would become known as the Great War (World War I), the British armed forces were using the Short Magazine Lee-Enfield (SMLE) rifle whose basic design predated the 20th century. The SMLE (known affectionately as “smelly”) fired the equally ancient (1888) .303 British round that was originally loaded with black powder, then cordite and eventually modern smokeless powders.

Using an earlier version of the Lee-Enfield against the Boers in South Africa during that conflict (1899-1902), some of the short comings of the system were realized. Some were corrected, others not, but eventually the Small Arms Commission began the search for a different design that would if not totally replace the SMLE, might at least augment the supplies of useable service rifles. Of the changes desired, one was a more powerful, flatter shooting round. Other desires were an action design more like the German Mauser with the magazine cut-off omitted and a one piece wood stock.

Early experimentation resulted in the 1913 Enfield rifle with tests being made using smaller caliber cartridges. Those early tests were conducted using both .25 and .27 caliber rounds. The quarter bore was dropped early on in favor of a .276 caliber cartridge with ballistics somewhat more impressive than the old .303 could muster. It did, however, along with more power, operate at higher pressures than some were comfortable with; and that, along with not wanting to introduce a different cartridge into the system, the decision was made to drop the .276 caliber idea in favor of the .303. This resulted in the final design and adoption of the Pattern 1914 Enfield (P14), also known as the No. 3 Enfield.

With war close at hand across the Channel, the British found themselves unable to tool up quickly enough to get the new rifle off the ground in a timely manner so turned to its ally the United States to get the rifle going for them.

Contracts were placed with Winchester and Remington Arms Co. of Ilion, New York and also Remington’s Eddystone, Pennsylvania plant to produce the P14 for the British. Later in the war when America was being inevitably drawn into the conflict, it too felt the need for another rifle to augment its own supplies of service rifles, the then current 1903 Springfield being in relative short supply with only about 60,000 rifles on hand. By 1917, the British had cancelled their contracts after some 1.2 million P14’s had been delivered. Thus, the same three manufacturing facilities that had been making the P14 for the British began in 1917 to make what amounted to the same rifle except for its caliber, the US .30-06, and designated as the Model of 1917.

Empire Influence

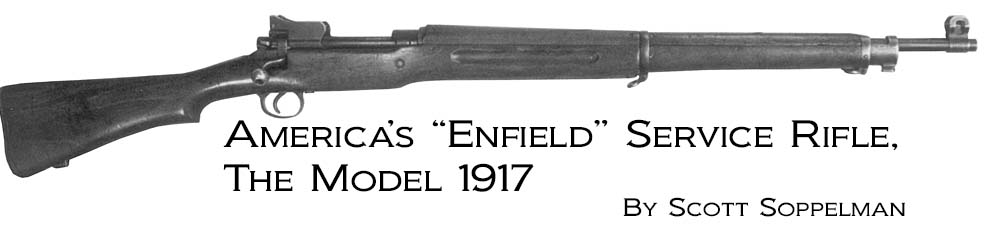

The Enfield rifle, whether in .303 or .30-06, looks like something dreamed up by the British. With the odd looking pistol grip and rear sight set-up, it sort of resembles an elongated SMLE No. 4 rifle. Its action was also of cock-on-closing design as is the SMLE. The one piece stock, one of the things the Small Arms Commission had wanted, became a reality as did the dual-opposed forward locking lugs on a solid bolt head. These can be viewed as improvements over the SMLE design. Its rear sight, similar to the SMLE was elevation adjustable for 200 to 1,650 yards on the P14 and 200 to 1,600 yards on the M1917. This may seem a little odd as the ’06 is a flatter shooting round than the .303. Both setups are meant for long range “volley” fire at massed troops, as accurate aimed fire at individual troops at ranges much further than 300-400 yards is problematic. Neither model’s rear sight is windage adjustable though the front sight can be drifted left or right. On the sample rifle used here, it is staked in place. The protective ears on the sights, front and rear, are certainly adequate for the job but give it an ungainly appearance.

The action itself, besides the cock-on-closing feature, is essentially a Mauser design. It is a controlled round feed design and utilizes a fixed ejector for which the left locking lug is slotted, and a full length non-rotating extractor. One area that differs markedly from the SMLE is its magazine. The SMLE uses a ten-round detachable box magazine while the P14/M1917 uses the more familiar fixed box, follower on spring set-up with a floor plate that can be removed with the use of a cartridge’s bullet tip or any pointed implement. The P14/M1917 system and the SMLE both use stripper clips to load their respective magazines. With either, loosing the box or floor plate would render the rifle to single-shot status but the loss of the floor plate would seem less likely than the SMLE’s box in the heat of battle. The stock of the P14/M1917 is supplied with three swivels, two for the sling and the forward being the stacking swivel common on many service rifles.

This series of rifles are large, heavy (9.3 pounds), and long. Its 26-inch barrel is a little longer than many service rifles of that era. Compared to the 1898 Mauser or 1903 Springfield with their 24 inch barrels and trimmer lines, the M1917 is something of a club. However, club or not, the P14/M1917 rifles were carried and used by the British and American troops “over there” in limited issue by the British and as a primary arm by the U.S. forces. More M1917 rifles were actually carried by our troops on the battlefield of Europe than were 1903 Springfields. Though officially designated as the U.S. Model of 1917, it is sometimes affectionately called the “U.S. Enfield” as a nod to its British origin.

Deficiencies

There has been some mention over the years in various sources about the receivers of some M1917 rifles, particularly those made at the Eddystone plant, that have developed cracks to one degree or another. Some attribute this to a problem of the heat treating process. In Frank DeHass’ Bolt Action Rifles, he suggests that because the barrels were screwed on to the receivers so tightly that perhaps the problem began there and was aggravated later when many rifles were rebarreled at arsenals or for sporterizing purposes. He suggests brushing a little gasoline on the receiver which, as it dries on the surface, is supposed to show any cracks as the gas will remain in them. It should be noted that any rifle of similar vintage should be fired only with mil-spec ammunition of modest pressure and not with hot handloads. Nevertheless, M1917 rifles have not had catastrophic receiver failure’s such as those that plagued low number 1903 Springfield rifles of Springfield Armory and Rock Island Armory manufacture. The only other problem of note as regards the P14/M1917 was early, fairly frequent ejector spring breakage for which a replacement part was made and retrofitted.

World War II

When the Second World War began, surplus U.S. stocks of M1917 rifles were shipped to England as part of the Lend Lease program. Most of these were relegated to training rifle status and/or issued to the Home Guard consisting mostly of farmers and men too old for active service. Some were put back into service on our shores as well; though with a pretty good supply of Springfields, both ’03 and 03A3 versions, plus the newer M1 Garand, then the current issue service rifle, the M1917 wasn’t really needed as a front line battle rifle. The M1917 was declared obsolete by the U.S. in October of 1945 just a couple of months after the end of the war. The P14/M1917 acquitted itself well during both World Wars serving in one capacity or another for the British and U.S. forces. While the British did not actually adopt it over the SMLE, it did at least perform well as a stop-gap and filled many needs often in a sniping role. For our forces it served as primary arm in World War I and as a standby in World War II.

Remington 1917

The sample rifle used here is a 1918 barrel-dated Remington built rifle. As is the case with most rifles of this vintage, the stock shows a fair amount of storage and handling dings and the metal shows some wear to its parkerized finish. Nonetheless, this particular test rifle is in very good condition with sharp rifling and very little throat or muzzle wear. Along with the barrel stamped date of 1918 is a large R denoting Remington manufacture. Winchester barrels were marked predictably with a W and Eddystone with an E. Later during World War II, some M1917s were rebarreled with barrels supplied by High Standard and Johnson Automatics. Other small parts were subject to replacement at this time as well so it is not uncommon to see a mix of R, W, and E stamped parts: this rifle being no exception. Also stamped on the barrel is the ordnance “flaming bomb” seen on most U.S. service rifles of that era. The only stock cartouche still visible is the P in a circle on the forward portion of the pistol grip.

Shooting the Enfield

Equipped with some varieties of .30-06 ammunition, the rifle was tested to see how it would perform using modern factory loads. Shooting was done from the bench on sand bags at 100 yards using the issue sights.

Starting with some mil-spec PMC 150-grain ball rounds, shooting began from a clean barrel. This particular load shot very high but was the only load tried that did so. It otherwise shot pretty well once putting 5 or 6 shots into about 2 inches. Other loads, including some from Hornady and Black Hills, performed in a similar manner depending on good sight picture which, on a cold, bright sunny day, was at times difficult. The load that offered the best placement on target was the 150-grain AccuTip loading from Remington. It grouped OK putting 5 of 6 in around 3 inches but was perfect for windage and elevation using the 200 yard setting with the “ladder” rear sight in the up position. The best single group was provided by Federal’s new Fushion 150 bullet offering. This load put 5 rounds in one and one half inches with four of those in one inch. Not bad for an 87 year old barrel with metallic sights.

Feeding of cartridges was not as smooth as with a Springfield or Mauser in part because of the cock-on-closing design. Ejection of empty cases was adequate though not spectacular and required a healthy bolt retraction to get them to fly well clear. This is typical of controlled round feed rifles however, and the rifle does have a long bolt throw. The trigger is the normal two-stage affair common to most service rifles; though it is not a hindrance. Handling and shooting of the big rifle is about what one expects of a well built service rifle and is quite satisfactory.

In comparing the M1917 service rifle to other service rifles of the time such as the Springfield or the Mauser, while an excellent rifle, the M1917 comes up short for several reasons. The M1917 is not as handy as the others, certainly it is heavier and longer and the action is not quite as slick handling as either of the aforementioned. Its sight set up is, however, superior to the early ’03 and any of the Mausers, which used an open barrel sight arrangement as opposed to a peep like the M1917. The later Remington and Smith-Corona model 03A3 rifles used a peep that was superior to any of these.

All of this aside, a soldier armed with an M1917 was well armed indeed, as the design is a solid one and well proven. In recognition of the M1917’s qualities, Remington used the basic action design to build its Model 30 sporting rifle line for hunters in several calibers besides .30-06. Remington knew a good thing when it had it.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V10N1 (October 2006) |