By Dean Roxby

Despite the similar name and subject matter, this new title is completely separate from the 1994 book Misfire: The Story of How America’s Small Arms Have Failed Our Military, by William Hallahan.

With that noted and out of the way, let’s look at the 2019 title by authors Bob Orkand and Lyman Duryea. Col. Duryea and Lt. Col. Orkand are both retired U.S. Army Infantry members, and both served in Vietnam during the early years.

Initially, I found this book somewhat difficult to read due to it jumping around in time too much. The first chapter begins by describing a January 1961 snowstorm in Washington, D.C. This leads into the inaugural ceremonies for President John F. Kennedy. In fact, I actually started reading it and then put it aside for later. Once I got past the first chapter, it generally went better.

Duryea and Orkand describe the trial by fire of the M16 rifle in the early days of the Vietnam War. It may be difficult to imagine now, nearly 60 years later and in service with over 80 nations, but the early versions of the rifle had serious issues.

As the book explains, there was a chain of events that led to many lives lost. This perfect storm of failures could have been avoided if the proper choices had been made.

To sum up, the ArmaLite firm had developed their AR-15 rifle using a specific load that used IMR-4475 (Improved Military Rifle) extruded smokeless powder made by DuPont™. This particular load gave an average velocity of roughly 3,150 fps, enough to penetrate a steel helmet at 300 yards. The Army insisted on a muzzle velocity of 3,250 fps in order to pierce a helmet at 500 yards. (The authors note that the NVA soldiers wore a soft pith helmet, while the Viet Cong seldom wore any headgear at all.) In order to achieve the higher velocity without exceeding the allowable maximum chamber pressure (52,000 psi), the IMR-4475 powder was replaced with a spherical “ball” type powder, WC846. However, while the chamber pressure was not exceeded, the port pressure was. As the bullet moves down the barrel, the pressure behind it begins to decrease as the powder is consumed. This pressure curve is different for each powder. Ball powder WC846 retains more pressure closer to the muzzle, so as the soldier’s bullet passed the gas port (a small hole in the barrel), the gas system was exposed to noticeably greater pressure.

This increase in port pressure caused a dramatic increase in the rate of fire, which in turn led to more parts breakage. Much more importantly, the jump in port pressure led to a surge in Failure to Extract (FTE) malfunctions. With the pressure in the barrel still high, the brass cartridge case was still expanded tightly against the chamber wall. This greatly increased the resistance of the empty case to slide out of the chamber as the extractor claw pulled on the case rim. In addition to the propellant issue, the chambers and barrels were not chrome-plated on the early rifles. In the very humid climate of Vietnam, corrosion soon set in, causing the chamber to become pitted. Perhaps the troops could have prevented such corrosion if they had been made aware of the issue and kept their guns well cleaned. This is the next great failure. The rifles often did not come with a cleaning kit. And, to make matters worse, the soldiers were often told the new wonder-gun did not need cleaning!

The result was huge number of FTEs during firefights, caused by a combination of excess port pressure and pitted and corroded chamber walls, brought on by a lack of training and cleaning kits. Once the rim had torn off the brass case, the only way to get the case out was to push it out with a cleaning rod. And, as noted, there were too few issued. The book refers to documented cases of troops under fire searching for a cleaning rod.

Unfortunately, the powers that be did not wise up to this problem nearly fast enough. The natural tendency of the upper military is to blame the troops on the ground. Duryea and Orkand state: “The first military reaction to poorly functioning weapons is to blame it on inadequate maintenance by the troops. A little bit of professional communication would have revealed that the problem wasn’t with the men. Many commanders looked no further.” And also: “This is a perfect example of senior officers out of touch with the men doing the fighting. The greater the distance from the action, the greater the tendency to discount reports from the field.” This is noted in chapter 5, called, appropriately enough, “CYA—The Name of the Game.”

As I mentioned above, chapter 1 is somewhat tedious to read. Chapter 2 gets into the technical aspects, including a brief mention of studies done in 1929 by the Ballistics Research Laboratory that recommended a smaller diameter round like .25 or .276. Naturally, the Army stayed with a .30-caliber round.

Chapter 3 looks at the early years at ArmaLite and of Eugene Stoner’s work there. It also looks at the Ordnance Department’s stubbornness to consider any outside designs (NIH, or Not Invented Here), and the .223/5.56x45mm round. This aversion to anything new also included the general concept of an assault rifle. The Ordnance Department loved their heavy, semiauto M14, not the light, selective-fire AR-15. Also discussed are Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and his team of “whiz kids,” young and bright, but with little military experience who tended not to listen to experienced military advisors.

Chapter 4, titled, “The Small Arms Systems Test,” looks at the SAWS test that took place between July and November 1965. Included in the test were the M14, M14E2, XM16E1 and the belt-fed M60 MG. The guns were put through a series of trials, with all potential issues noted. There was a list of 29 possible malfunctions! (Not every gun faced all issues. Number 29 is a partial misfeed from a linked belt and only applies to the M60.) This is where the problems faced by the XM16E2 should have been noted and corrected, if not already dealt with.

Chapter 6, “The Troops Deploy,” starts out a bit dry with a long detailed summary of which units went where in Vietnam. If you were there, you will probably enjoy seeing your unit listed. After several pages, it changes direction to discuss propellant characteristics, specifically IMR-4475 and WC846. Both powders were used in the M193 cartridge. Also mentioned is that the brass used in the cartridge case was not sufficiently hard. This caused the soft brass to flow into the tiny pits in the chambers, further adding to the resistance noted in the explanation above. I was not aware of this prior to reading this book.

Chapter 7 is written by Col. Duryea and describes the death of PFC Joseph Reid. Private Reid was the first soldier to die under Duryea’s command, and his death was directly due to an FTE. This is followed by a series of quotes from various sources, giving opposing opinions on the XM16E1. Several quotes are from the Ichord Subcommittee Report that examined the M16’s problems. In response to growing complaints about the rifle’s reliability, the House Armed Services Committee formed a subcommittee headed by Congressman Richard Ichord (D-MO). This report can be found on the web, if interested.

Chapter 8, “Someone Had Blundered,” continues with the Ichord Report and its findings. Some highlights include noting that the decision to use WC846 powder may have been influenced by the manufacturer Olin Mathieson’s “close relationship” with three Army commands involved with ammunition purchase. The report also states that it was “at least unethical” for Maj. Gen. Nelson Lynde, Jr., the commanding general of the Army Weapons Command, to jump straight to Colt immediately after retiring from the Army.

The book quotes a Small Arms Review article, “The M16 in Vietnam.

Just The Facts!” in Vol. 9, No. 5, February 2006 where Christopher Bartocci states: “The principal and most serious cause of the malfunctions of the AR-15/M16 rifle in Vietnam was the failure to chrome-plate the chamber.” However, Duryea and Orkand note elsewhere that clean new rifles would often have FTE issues with WC846 ammo and not with IMR-4475 ammo. Most likely, it was a perfect storm of pitted, non-chromed chambers firing soft brass ammo loaded with WC846.

Chapter 9 is written by Lt. Col. Orkand. It begins with the touchy subject of the role of media in the war. Orkand says: “It wasn’t the press that ‘lost the war’ in Vietnam for the U.S. The war’s outcome, to the contrary, was a self-inflicted wound resulting from decisions made by our nation’s totally befuddled military and civilian leadership.” The several pages of media issues also include President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America” comment, after watching CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite’s report in February 1968. The chapter then reverts back to further discussion of the Ichord Report. Orkand notes the tone of the report, with the words “unethical,” “unbelievable” and “borders on criminal negligence” quoted.

Chapter 10 takes a look at the TFX/F-111 aircraft project, of all things. The authors compare the TFX program to the M16 mess to point out McNamara’s faults. The Tactical Fighter Experimental eventually grew into the USAF F-111 Aardvark swing-wing jet. But it started out as a joint Navy and USAF fighter-bomber program. Both services were looking for new aircraft in the early ‘60s. McNamara ordered both services to work together on a joint design. He also felt the Marines and even the Army could make use of a jack-of-all-trades aircraft. In spite of the official selection board recommending the proposal by Boeing, McNamara ignored their choice and chose the General Dynamics design. The USAF also favoured the Boeing design. The Navy didn’t like either design but tried to develop a suitable variant. In 1968, after years of trying, the Navy cancelled its version.

Chapter 11 is a history lesson that deals with “Vietnamization,” the training of the South Vietnamese to fight on their own. It also looks at Code of Conduct issues and discusses corrupt Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) leadership and its effect on morale. A relevant point the authors make is: “No amount of training and equipment can offset corruption, lack of motivation and self-interest.”

Chapter 12, “Author’s Commentary,” Duryea comments on Colt continuing to test its guns with IMR-4475 ammo, while being well aware that the ammo used in Vietnam was WC846. Worse, the Army was also aware of this. For this, Duryea writes: “Colt and Army decision-makers were thus directly complicit in an unknown number of Americans killed in close combat, one of whom was my first KIA as a company commander.”

In summary, this book covers a lot of ground, not just the M16 woes. It looks at corruption in the ARVN, the role of media, the poor decisions made by LBJ, McNamara and Gen. Westmoreland. At times, I found it changing direction within chapters and to be rather repetitive on the propellant issue. It does cover an important period in U.S. military history through the eyes of two men who were there.

Early-Version M16s—A Perfect Storm of Failures

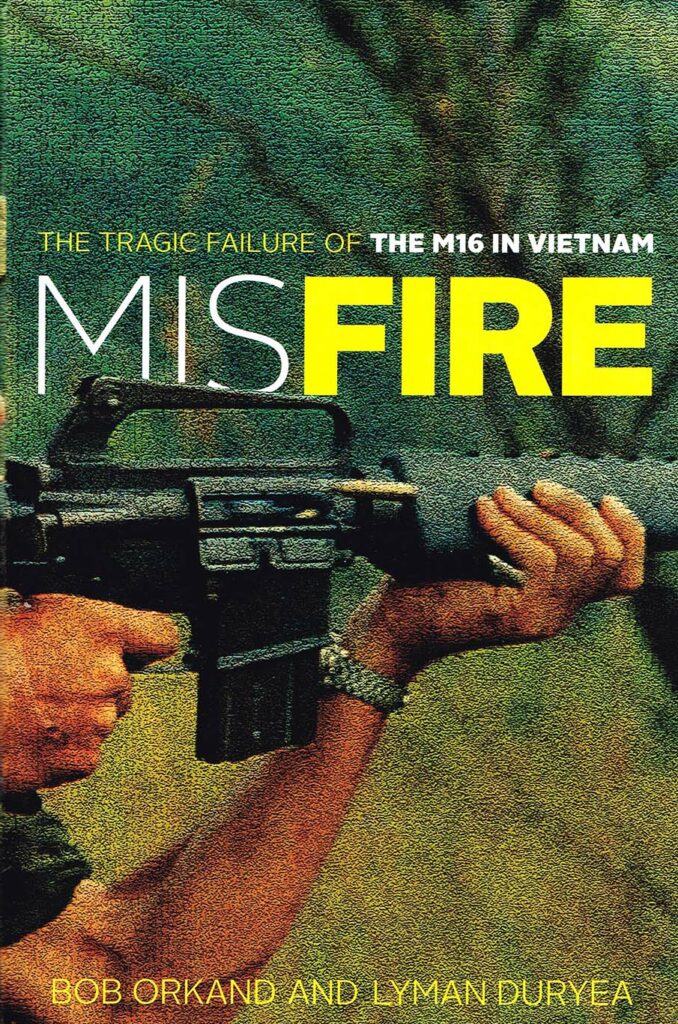

MISFIRE: The Tragic Failure of the M16 in Vietnam

Author: Bob Orkand and Lyman Duryea

Publisher: Stackpole Books

ISBN: 978-0-8117-3796-8

Copyright: 2019

Hardcover: 6.24”x0.87”x9.33”, 251 pages, with Color/B&W photos

MSRP: $29.95 (USD)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V25N1 (January 2021) |

![[Book Review] Misfire: The Story of How America’s Small Arms Have Failed Our Military](https://smallarmsreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/book-review-750x352.jpg)