By Anthony G. Williams

Throughout the first half of the last century, the great majority of sniper rifles were more or less modified versions of the standard military rifles, chambered for the standard rifle/MG cartridge. The growth of self-loading rifles during and after World War 2 saw sniper rifles departing from this tradition as the bolt-action type was generally retained for its greater accuracy. A further difference came when the standard rifles adopted lower-powered intermediate cartridges, much less suited to the business of long-range sniping. During the second half of the century, the military sniper rifle became a purpose-designed specialist instrument, capable of the highest practicable accuracy. This was usually complemented by precision-made ammunition, often loaded with heavier low-drag bullets, such as the 7.62×51 M118LR.

These developments have resulted in some superb equipment, but trends in accurate aimed fire can now be detected in two different directions: one is for the shorter ranges to be addressed by accurised self-loading guns providing faster repeat shots; the other is for guns firing more powerful cartridges being selected to increase the effective range. This article is concerned with the cartridges developed for meeting the second of these needs: long-range sniping.

To achieve a significantly longer range than the usual 7.62×51 requires at least a larger cartridge case to generate a much higher muzzle energy, and preferably a larger caliber as well; other things being equal, heavy large-caliber bullets retain their velocity better and are less affected by cross-winds. This was recognised by the first attempts to fire accurately at very long range; which often used anti-tank rifles of 13-14.5mm caliber. In fact, as early as the Great War, the 13mm Mauser M1918 anti-tank rifle was used in the counter-sniping role, although in this case the motivation was not so much to achieve long range as to punch through the armour plates being used to protect Allied snipers. The Korean War saw Soviet 14.5mm PTRD rifles being used for long-range fire, as well as and, on the US side, some experiments with .50 BMG guns. However, the guns were usually not that accurate and, even if they were, the standard production MG ammunition certainly wasn’t.

A change came in the 1980s from two different sources in the USA. One was the adoption of long-range anti-materiel rifles in .50 BMG caliber, not primarily for sniping but for attacking vehicles and other inanimate objects, normally using standard API or (later) Multipurpose MG ammunition. The other was the establishment of the .50 Caliber Shooters Association, promoting the use of this caliber for long-range civilian shooting, which inspired much more accurate rifles and ammunition. In combination, these two developments led to the use of .50 BMG rifles for long-range sniping as well as anti-materiel use.

There is a problem, however: the .50 BMG rifles and their ammunition are necessarily very big and heavy, not ideal for the sniping role. Many believed that a smaller, but still powerful, caliber would do that job more efficiently. As a result, specialised long-range sniping rifles are now available in several competing calibers. The ones described in this article are those offered in military sniper rifles; though there are a host of wildcats in addition. Furthermore, some anti-materiel rifles are also offered in the Russian calibers of 12.7×108 and 14.5×114, but these will not be considered here.

A high muzzle velocity is an advantage in long-range sniping, but that alone is not enough. As ranges extend, it is the ability of the bullet to retain its velocity which becomes increasingly important; bullets that slow down gradually are far more useful than those which rapidly shed velocity. To achieve this, the bullet needs a high ballistic coefficient (BC). This is achieved partly by using a bullet of exceptionally streamlined shape, and partly by making it heavy. It is worthwhile sacrificing some muzzle velocity in order to use a bullet with a higher BC.

The key yardstick for long-range sniper ammunition is the range at which the bullet drops below the speed of sound. This is important for two reasons. The first is because that provides a quick proxy for the trajectory and time of flight of the bullet; and the flatter the trajectory and the shorter the flight time, the greater the hit probability, other things being equal. The second is that dropping back through the transonic zone usually disturbs the flight of the bullet, adversely affecting accuracy, although this effect is minimised with the very low drag bullets developed for the more specialised calibers. To give an example, the 7.62×51 147-grain M80 standard NATO ball bullet is fired at a muzzle velocity 200 fps higher than the 175-grain M118LR, but drops to subsonic velocity at around 875 meters compared with 950 meters for the heavier and initially slower bullet.

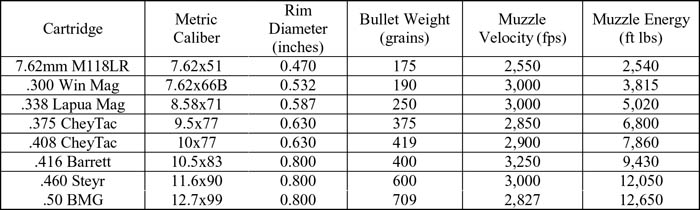

The table gives basic measurements and typical performances for the cartridges being discussed. The muzzle velocities and energies will of course be affected by the barrel length selected: figures quoted here are at the high end of the range. It is also worth remembering that some of the more specialised cartridges may develop higher chamber pressures than would be acceptable for a standard MG round, pushing their performance up quite significantly.

.300 Winchester Magnum

This was first developed as a commercial hunting round in the early 1960s. Work on adapting this cartridge for the long-range sniping role was undertaken by the USN in the 1980s to meet a special operations requirement for a rifle which would extend the 800 meter effective range of the 7.62×51 out to 1,200 meters. The standard loading uses a Sierra Match King bullet, which retains minute of angle accuracy out to at least 1,000 meters. This is in US service for special purposes.

.338 Lapua Magnum

Originally developed in the mid 1980s by the Research Armament Company as a long-range sniper round to meet the same USN requirement as led to the use of the .300 Win Mag described above, this was subsequently adopted by Lapua and is now made for both military and civilian requirements. The normal maximum range is regarded as 1,200 meters, but in ideal conditions it can reach out to 1,600 meters, the distance at which the bullet becomes subsonic. Many feel that this is a very practical round for sniping since the rifles are not much bigger or heavier than the .30 caliber weapons, and its use is spreading. The British Army adopted some Accuracy International rifles in this caliber some years ago, and recently announced its intention of replacing many of its 7.62mm sniper rifles by acquiring more of the .338 guns.

.375 CheyTac

The most recent addition to this field, this is simply the .408 CheyTac (see below) necked-down to the smaller caliber. It has been calculated that for the most potent loading, shooting 375-grain Lost River Ballistic Technologies solid copper-nickel alloy bullets at 3,050 fps muzzle velocity, the supersonic range would be around 2,230 meters. Wildcat versions of this cartridge, using very long 408-grain Viking bullets developed by Lutz Möller and fired at 2,854 fps, are claimed to achieve astonishing performances, with the supersonic range in excess of 3,000 meters.

.408 CheyTac

This round was developed by Cheyenne Tactical, LLC and introduced in 2001 in conjunction with its own range of sniping rifles. The original basis for the cartridge was the old .505 Gibbs big-game hunting round, but it has been much modified as well as necked down. The standard 419-grain Lost River Ballistic Technologies bullet remains supersonic and effective to 1,900-2,000 meters. A different loading, firing a lighter (305-grain) bullet at a velocity of 3,250-3,500 fps, has been developed to provide a flatter trajectory and shorter flight time out to 1,000 meters. The CheyTac rifle has reportedly been tested by the USMC, and sold abroad for Special Forces use.

.416 Barrett

This was developed recently by the famous maker of .50 caliber rifles, reportedly in irritation at a California decision to ban .50 cal. weapons. The basis of this round is the .50 BMG case, which is shortened and necked down. The performance is highly impressive, the standard bullet remaining supersonic to more than 2,250 meters. This bullet takes 2.5-2.6 seconds to reach 2,000 yards (1,830 meters) compared with 3.0 seconds for the .408 CheyTac. No service use is known at present.

.460 Steyr

This round pre-dates the .416 Barrett, being developed in the early 2000s by the Austrian Horst Grillmeyer, but adopts the same principle of shortening and necking down the .50 BMG case, this time to .458 caliber. Little information about the performance of this round has so far emerged, but very specialised long-range bullets have been developed for it, so it is reasonable to assume a supersonic range in the region of 2,000-2,500 meters. As with Barrett and their .416, Steyr Mannlicher can easily make weapons in this caliber by fitting new barrels to the .50 BMG rifles which they already offer. This also means, of course, that the guns are as big and heavy as .50 BMG rifles, so the customer will need to decide whether the ballistic advantages of these cartridges are sufficient to outweigh the loss of the wide range of ammunition types available in .50 caliber.

.50 BMG

The history of this old warhorse is too well known to repeat here. Apart from its usual MG loadings, specially accurate bullets and loadings have been developed for use in rifles, for example the Sniper Elite listed in the table above. Most military sniper loadings are limited in their performance by being restricted to matching the trajectory of standard .50 MG rounds, which means that they only remain supersonic out to 1,500-1,600 meters. More specialised loadings reveal a lot more potential. For example, the Hornady A-MAX 750-grain bullet, shown in the photograph, remains supersonic out to 2,250-2,300 meters despite having a muzzle velocity of only 2,700 fps.

In conclusion, the long range sniper is spoiled for choice to a degree never seen before, and the drive to achieve the best possible performance and accuracy out to astonishing distances is pushing forward the boundaries of bullet design and ballistics.

Anthony G Williams is an author and military technology consultant, specialising in small and medium calibre ammunition. He maintains a website at http://www.quarry.nildram.co.uk

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V12N1 (October 2008) |