By Will Dabbs, MD

The M1 Garand is an iconic American firearm. Little exemplifies the fighting men of the Greatest Generation like the classic M1. At a time when the U.S. military was almost criminally unprepared for war, the semiautomatic M1 Garand was a shining exception of a state-of-the-art Infantry weapon in widespread military use.

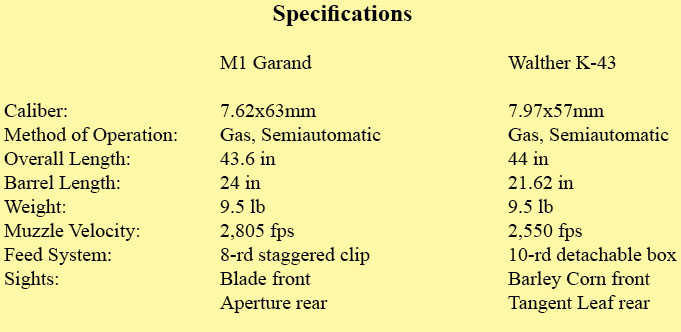

Designed by Canadian John Cantius Garand and accepted for general issue by the U.S. Army in 1936, the M1 became the archetypal rifleman’s rifle. Firing a full power 7.62x63mm (.30-06) cartridge, the M1 and its robust gas-operated action provided reliable fire out to the reasonable limits of the typical soldier’s skill. For all its legendary attributes and near-religious adherents, however, the Garand had a few shortcomings.

Principal among them was the method of feeding. The M1 feeds from the top via a spring steel en bloc 8-round clip that remains within the rifle as an integral part of the action until it is ejected after the last round is fired. The argument could be made that the perennial and eternal misuse of the term “clip” in place of magazine even in contemporary gun culture stems from the pervasive influence of the M1 upon the American lexicon.

While the clip feed on the Garand mated to a reliable semiautomatic action was an enormous improvement over the bolt action designs of most other contemporary nations, it was still slow and inefficient to service. The weapon had to be dismounted from the shoulder for reloading and it was remarkably difficult to execute this maneuver from the prone position or under cover.

Additionally, the Garand is long and heavy. This is not an issue when the weapon is only used on the local range. When you have to hump the rifle for twelve miles on a forced march or maneuver inside a building, these limitations are made painfully manifest. Lastly, the sling swivels on the Garand are mounted on the bottom of the rifle and are configured for drill use rather than tactical employment. On a long tactical march or in a CQB environment the Garand sling is fairly useless.

Generations

The M1 Garand is a product of a different time. Soldiers who trained with and employed the Garand in WWII had endured the deprivations of the Great Depression and looked at life in a way that we contemporary Americans cannot even imagine. A friend of mine, who hit the Normandy beaches around 1400 on 6 June 1944, carried a Garand for nearly a year in combat. He used his M1 to shoot an SS soldier through the head at long range on the grounds of Orly airport outside Paris. The perforated black German helmet with its SS runes attesting to the feat hung forgotten from a nail in the barn behind his house for decades – mute testimony to this humble soldier and the wartime exploits he would discuss only when pressed.

During the early days of the Battle of the Bulge my friend and his rifle squad were cut off from the rest of his unit. When trying to cross back into American lines, GIs made trigger happy by stories of Otto Skorzeny’s commandos operating in U.S. uniforms challenged his disheveled mob. Dissatisfied with the fact that my friend knew the current challenge and password the picket asked him who won the World Series in a given year. My buddy responded with some juicy profanity and the observation that he had no idea. He pointed out that when this man was comfortably watching baseball in New York he was hunting opossum in southern Mississippi forests to feed his family. The picket let them pass.

The point is simply that soldiers of this generation had to make do with less than is the case today. The M1 Garand used in this article exemplifies that axiom perfectly.

Touching the Past

This M1 is a rack grade Springfield Armory example purchased years ago through the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP). The CMP is itself a throwback to a better time in America when the government trusted civilians enough to sell them surplus military small arms. Suffice it to say that such a program would never survive the legislative process today. The finish on this rifle is about gone but it is mechanically serviceable. What is remarkable about the weapon is the condition of the forward hand guard.

At some point in the past the walnut hand guard split under hard use. Had this happened today the broken component would have been discarded and a new one installed. However, as previously mentioned, this was a different time. The hand guard on this rifle has been meticulously repaired by ripping slots cross-wise across the crack and filling the slots with wooden blocks before sanding the whole affair back to its original geometry and refinishing. The resulting component is still serviceable but now has character.

Meanwhile, in the Land of Darkness, Slavery, and Oppression…

The Nazis launched the Blitzkrieg that overran Europe in the opening weeks of World War II armed with what was essentially a WWI-era rifle. The KAR-98K employed the classic Mauser action that was arguably the finest manually-driven firearm design ever fielded. The KAR-98K fired a 7.92x57mm cartridge as fed via 5-round stripper clips. Despite the remarkable success of the German military juggernaut it soon became apparent that the KAR-98K bolt action infantry rifle was badly outclassed.

Design work began on a semiautomatic replacement for the KAR-98K in 1940 and eventually birthed the G-41. As was typical of wartime German design dogma, two companies produced competing designs that were tested in limited combat troop trials on the Eastern front. Walther and Mauser produced their own versions denoted G-41W and G-41M respectively.

The G-41 employed a novel gas trap design that was fairly effective but involved a great many precision machine parts and was only marginally reliable in the face of battlefield mud. It was also fairly nose-heavy in action. When confronted by the more utilitarian Soviet SVT Tokarev autoloading rifle the Germans were duly impressed and redesigned the basic G-41 action to make it more reliable and more easily manufactured.

The resulting G-43 employed a conventional top-mounted gas piston design copied directly from the Soviet SVT. The locking system incorporated into the bolt involved steel wings that were cammed into recesses milled in the receiver in the manner of the Degtyaryov DP-28 machine gun. A similar locking system lives on in the Combloc RPD light machine gun.

The G-43 was produced under unimaginably arduous conditions. Adolph Hitler’s megalomaniacal leadership had stretched German manufacturing and raw material reserves to the limit. In contrast to the objects d’art that the Germans produced in the 1930s, weapons and equipment produced in the final years of the war were roughly machined and in many cases shoddily produced.

One entire production facility used to produce this line of weapons was purportedly serendipitously destroyed during a strategic bombing raid intended for a V-1 rocket production plant. The plant in question was never rebuilt and that production variant ceased to be as a result.

Making Sense Out of Chaos

In the case of the G-43, the design was tweaked and adjusted throughout its production life in an effort to simplify manufacture and conserve strategic materials. The final iteration was termed the Karabiner or K-43. The transition in nomenclature from G-43 to K-43 was a change in name only purported to be at the direct command of Hitler himself. The G-43 was slightly shorter than the previous KAR-98K rifle and was deemed deserving of the Karabiner or Carbine title as a result. All G-43 and K-43 rifles incorporated a scope rail on the receiver though some were not finish machined. While there is a great deal of overlap in technical features among variants, the K-43 does typically have a larger stamped steel trigger guard than corresponding G-43 versions. This feature was incorporated to facilitate gloved use in the harsh winter conditions typical of the Eastern front.

By the end of the war the K-43 incorporated laminated Beechwood or even occasionally synthetic Bakelite stocks and maximum use was made of high-volume stamping and casting processes to minimize machine time. Markings were austere compared to earlier German designs and niceties such as threaded muzzles and detents on the sight adjustment ramp were gradually phased out in favor of volume production.

The K-43 series rifles employed a detachable 10-round box magazine and could also be loaded from the top via standard stripper clips. Troops were only issued with three magazines to go with these weapons as most loading was expected to be undertaken via strippers. Current estimates are that about a quarter million G/K-43 rifles were produced by the end of the war.

Boys and Their Toys

The weapon used in this article has itself a fascinating history. Picked up on the battlefield in 1945 by an American GI back when the country was sane enough to allow this practice, this particular K-43 was brought back home as a war trophy. In its original condition the rifle included a 4-power Zf4 scope. Finding that German 8mm ammunition was too scarce to allow the rifle to be used for deer hunting, the vet in question gave the gun to his young son. For years this fully operational German sniper rifle resided in the young man’s toy box and was regularly used in neighborhood mock combats with other young friends. Apparently none of the parents involved gave the practice a second thought. As there was no available ammunition the rifle was deemed safe enough to be used as a toy. Suffice it to say such behavior would likely raise a few eyebrows today.

During the course of countless neighborhood battles the front sight hood, magazine, and Zf4 scope were irrevocably lost. The hood and magazine have been replaced with late production versions. Combat abuse notwithstanding, it is a tribute to the German design that this rifle could endure nearly two decades of mileage on the imaginary battlefront while being stored in a toy box and remain in such good serviceable condition. Even the original leather sling is still in good shape.

Practical Tactical

On the range comparisons between these two well-used and high-mileage military weapons resulted in some interesting conclusions. For starters both old rifles were still completely reliable despite the fact that the K-43 was firing fairly vintage ammunition. This in and of itself was rather remarkable considering both these rifles rolled off of wartime production lines some 68 years ago. Both rifles weigh about the same and occupy a comparable geometric envelope so maneuvering indoors is a comparable chore with both rifles.

The K-43 is the more advanced design and tactical drills including reloads and immediate action were simpler and faster than those same exercises executed with the Garand. In both designs the bolt locks to the rear after the last round is fired but the removable magazine of the K-43 makes it easier to top off from under cover. The side mounted sling on the K-43 more readily lends itself to tactical use than the bottom-mounted version of the Garand. Additionally, the charging handle on the K-43 is on the left so the bolt may be dropped on a fresh magazine without taking the firing hand off the stock or rotating the action. Recoil is comparable with both weapons but they are heavy beasts so the experience is not unpleasant.

The sights on the Garand are the American military standard wide peep rear and winged blade front. Windage and elevation adjustments are embodied within the rear sight and are undertaken via large thumb wheels with positive detents.

By contrast, the sights on the K-43 have a more European flavor and consist of a hooded front blade and a ramp adjustable rear V. The K-43 sights are more difficult to adjust for elevation and there is no windage adjustment provision. In practical use the sights on the Garand are much quicker on target and easier to acquire.

The Garand is an overtly more solid design that feels more robust in actual use. The K-43 has a much sloppier feel. However, in this regard the comparison has a more apples-to-oranges flavor. The Garand was produced under secure conditions thousands of miles from the battlefront by a nation blessed with near-limitless natural resources. By contrast, the K-43 was produced in a nation bereft of young, skilled male workers under daily threat of aerial bombardment. Additionally, the inexorable allied advances had cut off the Third Reich from much of its natural resource base. Had the K-43 been produced under 1939 conditions it might feel yet tighter.

The trigger on the Garand is crisp and tight and readily lends itself to precision riflery. The same design has been used in both the Garand and its offspring, the M14, for match shooting since its inception. By contrast the trigger on the K-43 is sloppy, creepy, and long, no doubt the result of harried production and strategic materials shortages.

Despite the trigger disparity, bench accuracy was comparable between the two rifles and was still adequate for combat usage even after more than six decades of hard use. The two cartridges these rifles fire are ballistically comparable and are quite devastating out to the limits of the rifles’ accuracy capabilities.

Philosophical Musings

There are several conclusions that can be drawn from these two rifles, their backgrounds, and a practical comparison on the range. First, they really built quality firearms back in the day. The Garand in particular began life as an enormous block of ordnance steel and the action is nigh indestructible as a result. M1 Garands were still used in U.S. Army National Guard units well into the 1960s.

Additionally, for all their incontrovertible moral depravity, the Nazis made superb weapons. It has been said that wartime German engineers made the best weapons for the worst users and there is great truth to that axiom. Surplus G-43s were actually used as service weapons for years by the Czech Army long after World War II ended. Considering the circumstances under which they were produced the longevity of the G-43 design is remarkable.

The resulting cultural and societal commentary is all the more remarkable. Our nation is unrecognizable from what it once was and the transition has been so gradual that many who lived through it have been oblivious to the change. Like the classic boiled frog, the transformation has been so incremental that the enormity of it is not apparent unless observed from a detached point of view.

In World War II, young men, who in many cases were more familiar with horses than cars, or out houses and well pumps rather than indoor plumbing, donned uniforms and sacrificed to rid the world of a tyrannical dictator preaching a diabolical diatribe of hate. When they came home they brought with them the weapons of a vanquished army just as have warriors in every other culture since the beginning of time. These trophies, all operational and many of them full auto, hung above mantles, adorned veteran’s halls, and, in some cases, resided in toy boxes all across the country.

Members of the Greatest Generation darned socks, patched holes, and repaired equipment as needed to keep things going and useful in a time when dropping by Wal-Mart to pick up a replacement on the drive home from work was not an option.

Today’s warriors can be prosecuted for bringing so much as an enemy bayonet home as a memento of their combat tours overseas and American youngsters are suspended from school for chewing stylized handguns out of their Pop Tarts in the lunch room. In such a draconian, politically correct America, crime and general societal deterioration are made manifest on a scale literally unimaginable sixty-five years ago.

Six and one half decades ago the entire planet was locked in the most stark and overt battle between the forces of good and evil that the world has ever seen. As a result of the incalculable sacrifice of millions of American, British, Australian, and Canadian soldiers as well as those from dozens of other participant nations, evil was thrown back and crushed to allow the unquenchable spark of freedom to take light in areas previously smothered in darkness. As an ultimate result my son now drives a car produced by the same Japanese company that built A6M Zero fighters in World War II and the Germans remain some of our staunchest European allies today.

There is a great deal we can learn from the tools our forefathers used to determine the fate of the world. If we took the time to repair more and discard less the world might be a slightly better place. It strikes me as a healthy exercise to disassemble, assess, and compare these weapons to glean their cultural secrets. At the very least, it gives us cause to pause and ruminate on the sacrifices and triumphs of those who left their homes to go off to a foreign land and fight for freedom. We are the daily beneficiaries of their sacrifices today.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V17N4 (December 2013) |