By David Pazdera

In August 1948, the Czechoslovak Army introduced a brand new submachine gun, which at the time was at the absolute top of the world with its technical solution and performance. This success of Czechoslovak designers was all the more remarkable because it was achieved after only 2 years of intensive development without much previous experience with this type of firearm. The fate of this winning model, however, was soon affected by the political situation of that time period.

In the period between the World Wars, many high-quality automatic firearms were created in Czechoslovakia. In the case of submachine guns (at that time commonly called machine gun pistols), however, Czechoslovak designers kind of missed the proverbial boat. This was due to the lack of interest of the domestic Armed Forces, whose restrained approach towards an automatic firearm using pistol ammunition only began to change in the second half of the 1930s. Around that time, demand from abroad also started to grow.

The result was the first generation of Czechoslovak submachine guns:

- the model (“vzor” in Czech) 38 machine gun pistol using Czechoslovak 9mm model 22 ammunition designed by František Myška from Česká zbrojovka in Strakonice; although this type was officially introduced into the armament of the Czechoslovak Army in September 1938, Česká zbrojovka only managed to produce 15 samples before the occupation of Bohemia and Moravia; and the ZK-383 in the 9mm Parabellum calibre produced by Československá zbrojovka in Brno (main designer Josef Koucký) which, during World War II and shortly after, made it to series production in a limited number for export.

- In both cases, they were of conventional design with only some partial original touches. In the 1930s, however, Czechoslovak designers showed that even in this field they could come up with something original. In 1937, Václav Holek (1886–1954), a renowned creator of ZB machine guns, patented a feeding mechanism for submachine guns, where a ratchet wheel transferred cartridges in front of the cartridge chamber from the magazine parallel to the barrel. It is not yet known to what extent this idea was worked with before the German occupation, but it was the first promise of new directions of the Czechoslovak submachine gun design soon after the liberation of Czechoslovakia in 1945.

Calibre Plot

During World War II, the submachine gun changed from Cinderella to the queen of the ball. This radical change of the core of infantry armament affected the restored Czechoslovak Army as well, but only a relatively small portion of its members had combat experience. Although many weapons of German and other origins remained in the territory of Czechoslovakia after the War, the military administration soon sought to introduce modern models of domestic origin; one of the first models was supposed to be a submachine gun.

Its development was assigned to Czechoslovak firearm producers immediately in 1946. It was a competition of two traditional players: Česká zbrojovka in Strakonice and Zbrojovka Brno. Even though both companies were nationalized right after the liberation, the sharpness of the competition was in no way dulled. Both companies were very interested in the submachine gun contract for the domestic Armed Forces; they assigned their best people to the development, both closely followed each step of their competitor, and they did not hesitate to pull the strings behind the scenes.

One of the many development forms of the prototype ČZ 447—here with a two-arm folding metal stock.

One interesting moment was the choice of calibre. Before the end of the War, representatives of Czechoslovakia, under the so-called Košice Programme approved on April 5, 1945, committed themselves to the following:

In order to allow the closest combat cooperation with the Red Army, necessary in the interest of victory and our future, the organization, armament and training of the new Czechoslovak military forces will be the same as the organization, armament and training of the Red Army. At the same time, this will allow effective assistance of the Red Army and achieve the perfect use of its invaluable combat experience.

In the first post-war years, however, Czechoslovak experts saw this commitment as a general definition of the overall orientation of the restored Czechoslovak Army. It was quite rightly assumed that the Red Army, renamed to the Soviet Army in 1946, would use war experience to develop and introduce modern firearms and ammunition. In particular, the Soviet 7.62x25mm (Tokarev) cartridge, despite its impressive performance, certainly did not represent the ideal submachine gun ammunition.

Therefore, when ordering the development of submachine guns, the first calibre choice was 7.62mm or 9mm. In the second case, it was, of course, the 9mm Parabellum cartridge, which at that time was a proven western European standard and with which mass production Czechoslovak ammunition manufacturers had rich recent experience. Vědecký technický ústav (VTÚ, Science Technical Institute), renamed in 1947 to Vojenský technický ústav (Military Technical Institute), which ordered and managed development work for the Army, immediately recommended that the submachine gun design should use the 9mm calibre. Reasons: better “physiological” effect and simpler design of the cartridge case, which was expected to facilitate the development and production of prototypes. Even though selected prototypes were also modified to the 7.62x25mm calibre during the development, the results were not satisfactory.

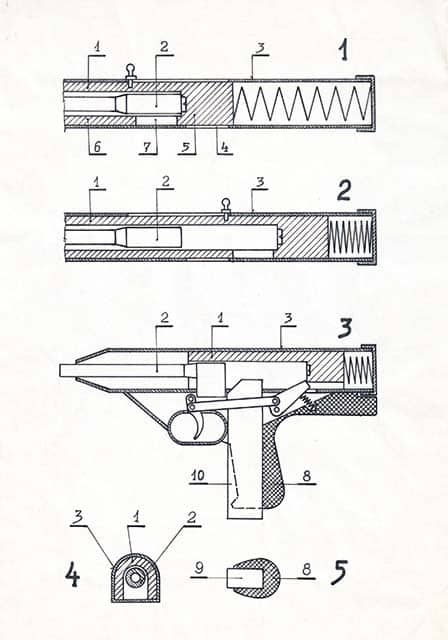

The function of the integrated magazine filler presented on the final development phase of the SMG “samopal vz. 48a.”

Wild Card

The wild card of this big game was the young designer Jaroslav Holeček (1923–1977), who during his compulsory military service caught the attention of his superiors with an unconventional submachine gun design. It first got him transferred to VTÚ and finally to Česká zbrojovka in Strakonice, where he worked even after being discharged from the Army in 1947.

Holeček was in many ways a controversial person who was not remembered in good light by his contemporaries, but many of his ideas had a healthy core and greatly affected the development of submachine guns. For the Czechoslovak military administration, it was a brilliant move to place this ambitious lance corporal in Strakonice. The Strakonice firearm design department excelled in effective teamwork regardless of personal relationships, and Holeček was forgiven for things that, in Zbrojovka Brno, would most likely get him dismissed very quickly. After all, the young designer shut this door himself with his very first prototype H/47, which was clearly inspired by the Brno development model ZB 1946 and subsequently evolved into the ZB-47 version, which furthered the aforementioned pre-War concept of V. Holek with a horizontal magazine.

The H/47 non-functioning prototype with a rotating segmented breech block was followed by the revolutionary H/para concept (abbreviated H/p), a special short submachine gun for airborne units. It is not yet known whether Holeček was acquainted with the experimental British World War II MCEM submachine guns, or if this solution was “floating in the air” as is the case with some ground-breaking ideas. The new Holeček gun stood out due to the use of a dynamic hollow slide that partially surrounded the barrel and a magazine placed in a pistol grip, so the gun’s centre of gravity was conveniently located above the shooter’s hand and did not change based on the number of cartridges in the magazine. In addition, the ejection port opened only at the moment suitable for ejection of the spent cartridge case and otherwise remained covered by the slide body.

This solution was patented by Česká zbrojovka (ČZ) and Jaroslav Holeček in 1947 and became the starting point for further development in Strakonice. The young designer also worked on the so-called rotary submachine gun ČZ 247 with an adjustable magazine well, which in 1948–1949 went into limited series production for the ultimately unrealized export to Egypt, but that was technically the last remnant of the interwar era. The future lay elsewhere.

Deserved Victory

The submachine gun competition was suspenseful until the last moment. Česká zbrojovka quickly developed the H/p concept into the successful prototypes ČZ 447 (with a folding stock) and ČZ 148 (with a fixed wooden stock). Since autumn 1947, Zbrojovka Brno countered with the similarly designed ZK 476 of Koucký brothers.

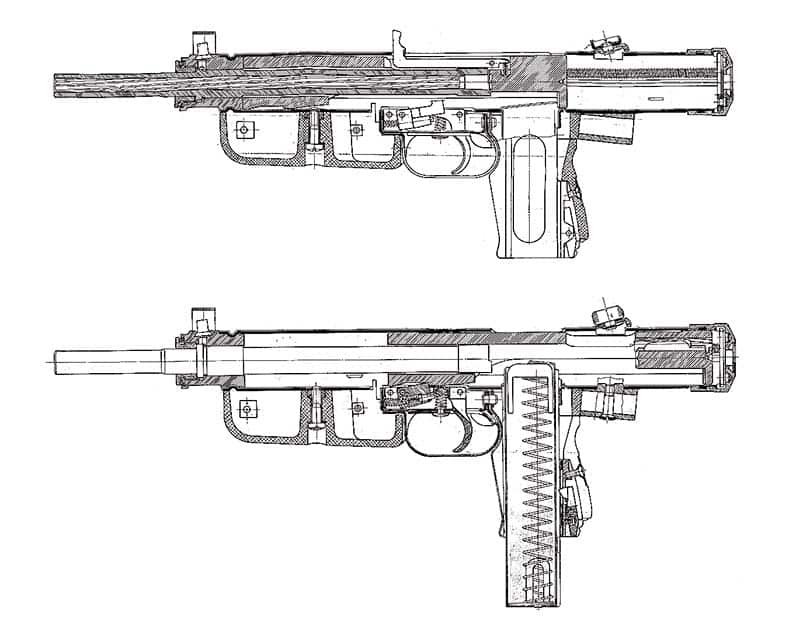

Holeček’s design was being evolved by many other designers, mainly František Myška, Jiří Čermák, J. Keliš, Václav Zíbar, Jan Kratochvíl and František Brejcha. It should be added that the development involved many more workers of the Strakonice and Uherský Brod plants of Česká zbrojovka and that the resulting submachine gun should therefore be considered a truly collective work. Jiří Čermák (1926–2006), the future author of the excellent Model 58 submachine gun, soon came up with a crucial idea to change the transition from the angular profile of the slide (and hence the slide itself) to a circular profile. This shape modification not only brought several design advantages but also greatly simplified production. This proved decisive.

The model 48a (23) SMG after basic disassembly. This is one of the few pieces brought back to the Czech Republic by the company Zelený sport.

After fine-tuning countless details, in summer 1948, there were two similar finalists to choose from, with no comparable competition in the world. VTÚ ultimately opted for the manufacturing simplicity of the Strakonice prototype. Other advantages of this firearm, compared to the Brno model, were lower weight, simpler design, easier handling, simple integrated filler and closing of the ejection port outside ejection, protecting the mechanism from dirt.

It was a well-deserved victory, because, despite the similar parameters of the final prototypes, the Strakonice type maintained the lead over the Brno model. In spring 1948, when VTÚ came up with the requirement for versatility (i.e., the possibility for easy replacement of a fixed stock with a folding stock), Česká zbrojovka engineers reacted quickly. Their solution was perfected by the director of the Uherský Brod plant, František Brejcha. J. Čermák, who managed to quickly resolve the additional requirement for barrel replacement for blank cartridge shooting; the barrel was attached in the receiver using a nut with front protrusions and could be released by the front end of the slide. Thanks to the barrel attachment method, the submachine gun also achieved higher accuracy than other weapons of that time and category. The integrated ammo clip magazine filler on the right side of the forend, which was designed by Václav Zíbar and first appeared on the ČZ 247 model, was greatly praised as well.

Other notable design elements of the Strakonice model include:

- oblique square bowl-shaped rear sight adjustable from 100m to 400m, on which the notches were laterally offset to always eliminate projectile drift; i.e., its lateral deviation in the rotation direction, at the appropriate distance (design of V. Zíbar);

- F. Myška’s anti-rebound safety of a design similar to that of the ČZ 247 submachine gun perfected by J. Kratochvíl, so that the groove for the cocking arm did not have to stretch to the end of the receiver;

- Holeček’s trigger mechanism that allowed switching between single-fire and burst fire by naturally increasing the finger pressure on the trigger (again a variation of the solution used in the ČZ 247); and

- J. Holeček’s successful one-arm stock, which could be folded in a horizontal plane and fixed in the folded position by means of a rotating butt, which in this case could be used as a grip or folded to a horizontal position for easier transport.

Two Names

On August 10, 1948, the armament committee decided to introduce the ČZ 447 submachine gun into the armament of the Czechoslovak Army, where the new firearm was designated “9mm samopal vz. 48a (pěchotní),” meaning “9mm model 48a submachine gun (infantry version),” and “9mm samopal vz. 48b (výsadkový),” meaning “9mm model 48b submachine gun (paratrooper version).” At the same time, the corresponding ammunition was officially standardized as well, first under the designation “9mm ostrý náboj,” meaning “9mm live cartridge” (steel-core bullet, weight 6.42g) and “9mm ostrý náboj T” meaning “9mm live cartridge T” (lead-core bullet, 8g). The Army preferred the version with the lighter bullet, later named “9mm náboj do samopalu se střelou vz. 48” (“9mm submachine gun cartridge with model 48 bullet”). There was also training ammunition.

The only difference between the infantry and the paratrooper design of the submachine gun was that the former had a fixed beech stock and the latter had a folding stock, but both parts could easily be replaced after loosening a single screw. The version with a folding stock and short magazines was primarily designed for airborne and communications units and for operators of artillery weapons. The infantry model was used by motorized infantry and other units.

Czechoslovakia thus became the first country that equipped its Army with a submachine gun with a slide around the barrel and a magazine in a pistol grip. This remains the case even though the slightly younger Israeli UZI, allegedly inspired by the Czech model, gained more popularity. Here it should be noted that if the Israelis really borrowed some ideas from Czechoslovaks, they were based on the ZK 476 model from Brno, which they were able to study quite thoroughly.

Changing of the guard in 1953. Since 1951, the Czechoslovak Army started to use the new models 24/26 in the 7.62x25mm calibre, while the 9mm SMGs were gradually handed over to the Czechoslovak security bodies and later exported in great numbers.

The Final Form

The model 48 submachine gun took its final form in the first months of 1949. Until then, modifications were carried out according to the requirements of the armament committee of August 1948. One of the most noticeable changes was the transition to a trapezoidal magazine. In Czechoslovakia, this innovative, originally Swedish design element improving the guidance of cartridges into the chamber, was first applied to the ZK 476 submachine gun in connection with the demand of the Swedish Army and later requested by VTÚ for the competitor’s ČZ 447 in autumn 1948. The transition to the trapezoidal profile of the magazine was the last major change in the design of the new submachine gun. Although some changes in the firearm and its accessories were made during mass production, they were only minor modifications of a technological nature.

The official name was unusually changed in the spring of 1950 as part of the transition to a new system of code names of Czechoslovak military material. The gun was renamed to “samopal 23” (with a fixed stock) and “samopal 25” (with a folding stock). The number in the name did not mean the traditional model number with reference to the model year, so writing submachine gun “vzor 25” (“model year 25”) is wrong. This error, however, was frequently made by the Army itself as well as the production plant. It was no coincidence that this unusual nomenclature was soon abandoned. In any case, the new submachine gun became popular among Czechoslovak soldiers under the nickname “pumpička” (pump), which is still used today.

Production in Uherský Brod

During development, it was clear that the production of the new submachine gun would be assigned to the Česká zbrojovka branch plant in Uherský Brod (today’s Česká zbrojovka a.s.). The deciding factors were a strategic location far from the western border of Czechoslovakia, good machinery and solid experience—most recently with the production of ČZ 247 for export. The parent plant in Strakonice accepted the role of a subcontractor of some small parts, whose production could be transferred to another metalworking plant without any problems.

The Uherský Brod plant received permission to start mass production of model 48 submachine guns in February 1949. The first 200 firearms were made in June of the same year, and the production involving nearly 800 workers (including a large number of women) quickly gained momentum. By the end of 1949, the plant produced a total of 26,770 infantry and 10,000 paratrooper submachine guns. In 1950, when the production of the 9mm submachine guns culminated (and when the production plant become an independent, state-owned enterprise under the name “Závody přesného strojírenství Uherský Brod” or “Precision Engineering Plants Uherský Brod”), 60,458 infantry and 70,820 paratrooper submachine guns were produced.

In 1951, the production ran down. It definitely ended in mid-March (only manual adjustment and assembly remained) after producing a total of 6,346 model 23 submachine guns and 25,611 model 25 submachine guns and was followed by the production of new 24/26 models in the 7.62x25mm calibre.

Between 1949 and 1951, according to factory reports, a total of 200,005 model 48 (23/25) submachine guns were produced. The version with a folding stock was in a slight majority. These firearms had to be accompanied by many hundreds of thousands of magazines (the vast majority of which was 40-round; the amount of shortened 24-round magazines was significantly lower), nearly 80,000 training barrels, a large number of cleaning rods and, of course, spare parts.

As for the training barrels, they were originally designed for cartridges with bullets made of roasted alder wood, which was a continuation of the traditional design used in the interwar and post-war Czechoslovak Army. Due to unsatisfactory function, however, a training barrel for blanks with a constricted case mouth was soon developed.

To the World

Model 48 (23/25) submachine guns were primarily designed for the Czechoslovak Army, but right from the start of the production, they were also supplied to the National Security Corps–the Czechoslovak uniformed police of that time. Two hundred thousand guns that were produced were far from enough for these purposes.

The new submachine gun was introduced into the armament almost half a year after the Communists gained control over Czechoslovakia and pushed for orientation towards the Soviet Union in all spheres. However, changes were rarely immediate and, specifically in the area of armament, on-going projects were still calmly running down. The radical turn came with the advent of a new Army class in April 1950, which began to abide by a strict interpretation of the Košice Programme.

In the case of submachine guns, this resulted in the immediate termination of the production of the 9mm model and its rapid adjustment to the Soviet 7.62x25mm cartridge. The officials did not address the increased costs and noticeable deterioration of some parameters of the weapon; instead they were driven by “unification” of the Czechoslovak armament with that of the Soviet Army’s. The biggest irony in all of this was that, due to the concealment tendencies, Czechoslovakia was not informed that the Soviets had already switched from the 7.62mm cartridge to the new 9mm Makarov cartridge.

The 9mm 23/25 submachine guns, the best weapons of their category in the world at that time, thus became unwelcome guests in the Czechoslovak Army. From 1951, they were being moved to security bodies (including the Border Guard), where they formed the backbone of personal armament until the 1960s.

However, the discarded 23/25 submachine guns became a successful export article, by means of which Communist Czechoslovakia, in accordance with the current politics of the Soviet Union, supported friendly countries of the Third World. Refurbishment of the firearms for this purpose was carried out since the second half of the 1950s once again by the Uherský Brod plant. Export of 23/25 submachine guns would be a topic for a separate article, but we should at least mention that the largest customer was Castro’s Cuba, which received a total of 100,000 guns.

Because the 9mm 23/25 submachine guns scattered around the world, most often to truly “hot” locations, today’s shooters and collectors in western countries do not come across them very often. If you ever have the opportunity to try this ground-breaking firearm, do not hesitate. Ammunition should not be a problem; you can use today’s versions of 9x19mm. If you are spoiled by systems with front firing, you have to get used to the noticeable movement of the heavy dynamic slide before the actual shot. But once you learn the right grip and proper triggering—you choose the firing mode by the amount of finger pressure on the trigger—you will find that 23/25 submachine guns had and still have a lot of upside, especially when you also get familiar with the sophisticated folding stock or very simple disassembly.

QUICK COMPARISON

| Submachine Gun | Model 48a/23 | Model 48b/25 |

|---|---|---|

| Total length (mm) | 680 | 444 (with folded stock) |

| Barrel length (mm) | 285 | 285 |

| Sight radius (mm) | 270 | 270 |

| Weight (kg) | 3.13 (with fixed stock) | 2.96 (with folding stock |

| Magazine capacity (rounds) | 40 | 40/24 |

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V24N3 (March 2020) |