The Military Historical Institute of Prague in Czech Republic has got a great many unique and experimental firearms, both of indigenous and foreign origin. But even amongst these unique guns one can sometimes find a gem – such as this gas-operated, belt-fed general purpose machine gun (GPMG) neatly marked “MG 39 Rh” on the side.

For years it was listed as lost forever during the war, and known only to a handful of experts from mere footnotes in the 1937 machine gun contest files. But even though Nazi German weapons, especially the automatic weaponry, are still amongst the world’s hottest and favorite topics for researchers and collectors alike, this machine gun, even though as of 1962 no longer confined to the classified military small-arms research institute, still had no fitting description in books or otherwise outside Bohemia. This is not to mean that it was thoroughly researched in Bohemia, either: but at least there was an article describing it, published in the sadly late Strelecki Magazin shooting monthly in the year 2002.

Pride and Prejudice

The German military of the 1920s and 1930s was irrationally prejudiced against drilling bores – gas-operated automatic firearms were a major no-no. Up until the time of introduction of the G.43 rifle, German military scientists and technicians held that drilling the bore would obligatory and unfavorably influence the internal ballistics of the gun, ruining accuracy and service life.

It took a major generation change in Germany’s firearm’s industry’s main client, the re-born German Wehrmacht, to tumble down the walls of prejudice. The older generals, dyed-in-the-wool theoreticians, were now phased out by young practitioners, who all-too-well remembered from the first-hand experience in the fields of Champagne and Verdun, that French gas-operated air-cooled Hotchkiss machine guns were every bit as deadly, accurate and dependable as the German recoil-operated water-cooled Maxims.

It was not earlier that Hitler gained power and renounced the Versailles Treaty in 1935 that the Wehrmacht was re-born and these young lions could seize power in the rapidly growing organization. It was only then, and still with great deal of trouble, that the gas-operated automatics started to compete for the major military contracts. There still was a long and convoluted way ahead of them – as attested by the ordeal of the G.41. It was the first ever gas-operated gun to enter Wehrmacht armament – but alas the military forced upon the Mauser company that even though it was gas-operated, there dared not to be any openings drilled in the bore, and the gases were vented from the muzzle, using the Bang principle, which unreasonably complicated the already not entirely straight forward mechanism.

That the military went against bore-drilling doesn’t necessarily mean that all of the German gun industry was equally prejudiced and obsolete. Quite to the contrary – for each Wehrmacht contest gas-operated guns were proposed, but lack of financing, combined with subsequent lack of experience with such designs and the proverbial German prowess at inventing problems meant that none of these were granted a fighting chance of getting through the obstacles cast in their way by the military. Walther got nearest to designing a practicable gas-operated semiautomatic rifle in A.115 – but their gas-openings were not only twin (the gas was bled to a sleeve around barrel with a donut-shaped piston) but way too large (in excess of 3 mm), as if to make a point that bore drilling would do no good. Then Vollmer designed the A.35, world’s first gas-operated intermediate-cartridge assault rifle – but then put that much a complicated clockwork inside, that it would have been unreasonable of the military board of review to green-light it into mass-production. Against that background, the Rheinmetall gas-operated machine gun seemed to be a much more mature and sounder design.

The Rejected Prototype

The history of the MG 39 Rh began in 1937. In that year the Heereswaffenamt (HWA, Land Forces’ Ordnance Office) having solved the GPMG issue with a temporary fix of the MG 34, set about to designing a machine gun of the future German Army, an “Objective GPMG,” as it would be probably called today. In comparison with the MG 34, the future GPMG was to put up a higher rate of fire, be less complicated, more reliable, better suited to mass-production through the use of modern technology (e.g. sheet-metal stamping and spot-welding) to cut down machine time and skilled labor requirements. In February, 1937 a tentative green light was given to the idea of a sheet-metal stamped machine gun, and the HWA sent requests for offer to three companies: Rheinmetall-Borsig’s filial in Sömmerda, Johanness Grossfuss in Döbeln, and Stübgen of Erfurt. Of these, the Sömmerda’s Rheimetall (part of the Borsig railway stock and machinery giant as of January 1936) was Germany’s prime machine gun clandestine designing center since 1918, doing most of the prohibited machine gun development by lieu of its Swiss filial – the Solothurn company, set up especially for that purpose. Its residing designing genius was no less than Louis Stange – the guy, who gave the Nazis the MG 15, MG 17, MG 34, MG 81, FG 42 and many other famous German automatic small arms.

The companies were asked to design a machine gun based on sheet-metal stamping technology, with tolerances looser than the MG 34, with receiver roomy enough to accommodate debris and dust – but using as much MG 34 accessories as possible, including the Gurt 33 or 34 non-disintegrating ammunition belts. Other than that, especially as to the future machine gun’s method of operation, the designers were given a free hand, providing their gun would work reliably with the standard German ammunition, the 7.9mm x 57. The whole project was then still mostly an experiment, and the central funding available was a token one at best, therefore no finished weapons were required, just mock-ups. On October 26, 1937, Rheinmetall and Stübgen both submitted gas-operated guns, while the Grossfuss gun was a short recoil-operated one. The Stübgen gun was canceled even at that early stage, while functional models were ordered of the Rheinmetall and Grossfuss entries, the latter openly favored by the military as the short-recoil design. In April 1938, Stange’s gas-gun shot the living daylights out of the Grossfuss’s recoil-operated model, but once again the old ways spelled the doom for the Rheinmetall. Despite the disastrous results at the shooting range, the military chose the yet-imperfect recoil-operated gun. With lots of TLC from the HWA officials, the lame duck was soon rectified enough into World War II’s most feared machine gun and still, after 70 years, a mainstay of many armies all over the world, including prime NATO countries like Germany, Turkey, Italy, Denmark or Norway – the MG 42.

Rejected – But Not Abandoned

Despite the thumbs-down from the machine gun contest board, the company decided to go along with the design, which they deemed still promising – and so much at that, as to fund the development from their own pocket. Rheinmetall, cooperating with Germany’s armies since 1899 had much experience in dealing with the military. They knew that while in a pinch, the HWA would buy their gun, drilled bore or no drilled bore. Should the Grossfuss prototype fail, they would be waiting in the wings with a perfected model, ready to be introduced overnight. And should the Grossfuss prototype eventually win… well, at least they would die trying.

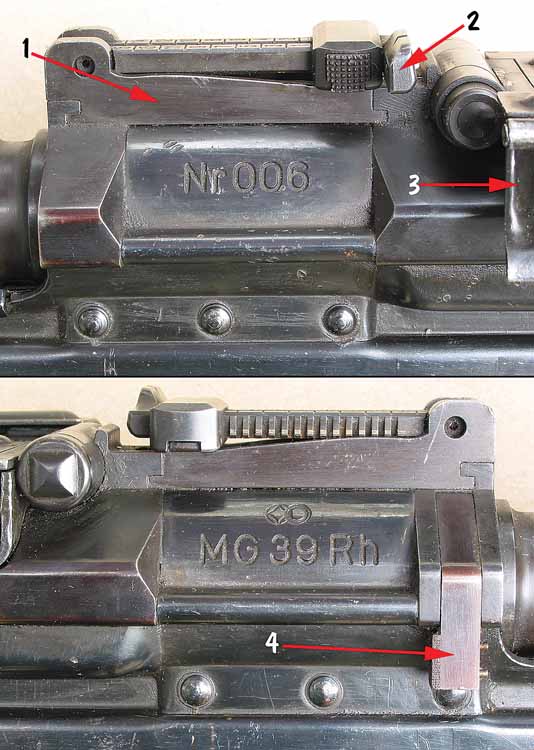

We lack the records to confirm or deny that perfected Rheinmetall gun was ordered for the 1939 Döberitz trials that resulted in accepting the recoil-operated MG 39 from Grossfuss. The MG 39 Rh from Prague is serial numbered 006, which tends to prove only that at least five others were made. Or some more, as there are also other serials on this gun. The bolt is electro-etched 09, while the buttplate has 29 struck to it – both could indicate that more MG 39 Rhs were made: at least 3, but possibly as many as 23. The company took two patents for the gun, and both (DE 712 136 and DE 724 418) were signed on by Louis Stange. The quality of manufacture is very high: this is certainly not some workshop model, but a machine-manufactured, at least semi-serial produced weapon. Interestingly enough for every Nazi gun buff, there is not a single Waffenamt mark, anywhere, which clearly denotes that the MG 39 Rh has never been a military small arm.

Czech Connection

That the MG 39 Rh was preserved in Prague may be just a coincidence, but it has got very much in common with the Czech machine gun designing “school,” especially with Vaclav Holek’s masterpiece, the ZB-26, eventually developed into the magnificent Bren LMG. No doubt that the ZB-26 must have impressed Stange – but of course he was not a copyist but a great designer in his own right, so the influences are to be derived, not just pointed to.

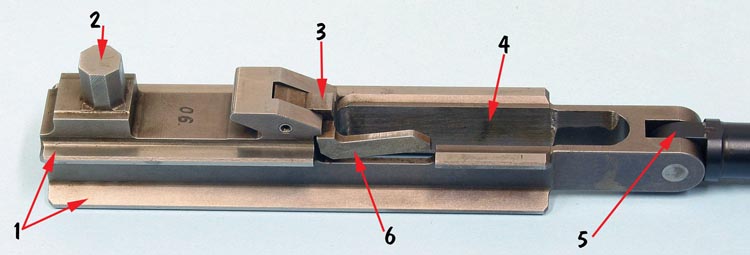

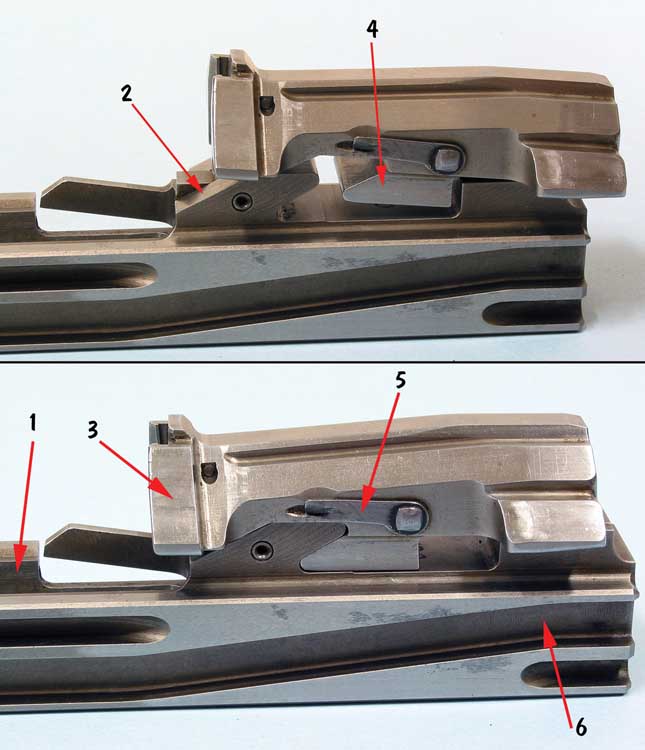

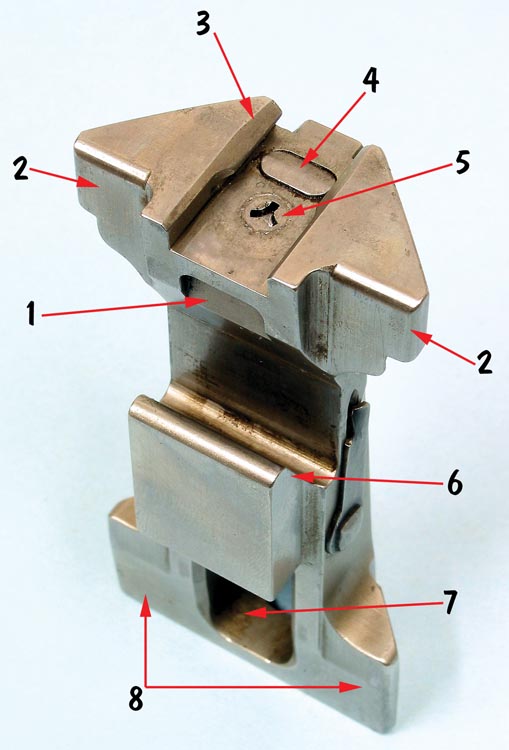

All modern German small arms were locked by rotating bolt – but all of a sudden this gun has a tilting bolt locking, like the ZB-26. The bolt carrier has bolt unlocking ramps, the firing pin is contained within the bolt and struck by a separate projection on the bolt carrier – again, like in ZB-26. The bolt is locked by tilting within the receiver, but the locking abutment is not located in the upper rear part of the receiver, where the locking shoulder of the bolt is forced into by the ridge on top of the ZB-26 bolt carrier. Instead, in the MG 39 Rh, it is the front part of the bolt that tilts up for locking. In the last phase of the forward stroke by the bolt carrier, the bolt meets the barrel mounting block and stops there, but bolt carrier still moves forth, forcing the front part of the bolt to tilt up and locks it. This change was forced by the changes in receiver design. In the ZB-26 the receiver was machined, having plenty of strength to support locking. In the MG 39 Rh, the receiver is made out of spot-welded and riveted stampings, and the only element stout enough to withstand the forces involved is the barrel mounting block, a machined core of the riveted and spot welded receiver. This is where the block is mounted, this is where the sight is mounted, and this is also a point, where locking abutments were placed within a small extension projecting rearwards. The locking lugs are lower points of (almost) triangular-sectioned bolt head, rising there while the bolt tilts, actuated by the bolt-carrier. Most of such designs are turn-bolt locked – why would Mr. Stange choose to involve that unnecessary complication of tilt-locking in a stamped receiver would forever remain a well-guarded secret.

The firing is accomplished in a manner very close to the ZB-26 – but not that of a Bren, where the front portion of the central unlocking post serves as a “hammer” to administer a blow on the firing pin. In the MG 39 Rh, as in ZB-26, there is a separate firing projection at the rear of the bolt carrier – octagonal in section of all available shapes.

After the shot is fired, expanding gases pushing the bullet down the bore reach the gas-opening and some of it is vented to the gas-chamber where it pushes the gas piston (and with it – the bolt carrier) back. The bolt carrier slips from under the locked bolt and the rear ramp of the unlocking projection mates with the unlocking ramp cut into the bolt and starts to tilt it down, to unlock. When the unlocked recoiling parts start their rearward stroke, the transport lock lever on the right side of the bolt carrier mates with a channel in the receiver wall and rotates, latching the bolt with the other arm. From that point on the bolt is rigidly locked with the bolt carrier and remains so for the duration of the recoiling parts reciprocation. It is not until another shooting cycle is started (this is an open-bolt design) and the bolt strips another cartridge from the belt that the bolt is again free to tilt after the locking lever exits the receiver channel again.

Chambering and Extraction

The belt is fed from the left side of the feed tray, exactly like in all other German machine guns. The belt itself was also a standard wire-bound, open bottom, non-disintegrating links “direct-feed” Gurt 33 or 34. The bolt, however, had not the common spring-loaded extractor, but a Browning-style rigid gutter cut into the bolt face. What’s even more surprising, given the shape of the claws and the tilting motion of the bolt, it is obvious that the cartridge rim is NOT held in it during the firing. It is only at the beginning of the unlocking, when the bolt dips from the locked position, when the claws enter the groove. And the grip was not a very tight one, necessitating addition of the special spring-loaded rim stabilizer, supporting the upper part of the case head during extraction in order not to allow the case to slip out too early. Again – why such an experienced designer went to such frivolity will probably never be known. It is possible though, that the normal spring-loaded extractor would not fare better, giving the magnitude of the front-oscillating movement of the tilting bolt design – after all the ZB-26 was a rear-tilter and breech face made only minimal movement.

If the extractor seems unusually complicated, the ejector was as far from mundane. It was an oscillating or “see-saw” type, shaped like a cavalry spur. It has two arced members straddling the bolt, with an ejector plunger projecting downward from the junction of the said members. It was suspended with two separate pivot-pins, one each side of the receiver cover, supported by its own operating springs and operated by the reciprocating bolt. Close to the point of rearmost recoil, the bolt hits the sloping rear ends of the ejector, violently dipping the front end, with ejector plunger striking the case body like a guillotine and throwing it out of extractor claws through the bolt carrier ejection port into the bottom ejection opening of the receiver. Today, lever-type ejectors are quite common in retarded blowback guns, like Swiss StG57 (SIG510) or the HK series – but way simpler in manufacture.

The recoiling unit’s weight was a mere 790 grams – which is really not much: some of the blowback submachine guns had bolts weighing in at similar level. It consisted of a bolt carrier with a long-stroke articulated gas piston and tilting bolt. The bolt carrier governs the functioning of all other machine gun mechanisms. There is a locking/unlocking projection there, as well as the bolt transport lock, the belt-feed lever cam path, sear notch and safety sear notch (tripping the sear in case of insufficient recoil), as well as a firing post (striking firing pin in battery) and ejection window.

Unfortunately, the surviving specimen is incomplete, so one can’t tell how the bolt cocking lever was shaped (and even positioned). The only thing that is left is a long bottom slot, a rear portion of which serves as an ejection opening, closed by a sliding cover with a spring-loaded retainer, released by the recoiling bolt-carrier, exactly in the manner of the ZB-26, ensuring automatic opening at the latest by the first shot fired.

Weird and Weirder Still

By far the most untypical part of the MG 39 Rh is the firing pin, the cross-section of which resembles the three-pronged Mercedes star, covered by patent DE 724 418. This was surely done in order to strengthen the firing pin – but was it worth the complication of cutting a Y-shaped firing pin opening in the breech-face? The patent description clearly states the reason for that complication: if the conventional round-sectioned firing pin stuck in the breech-face, violent movements of the front-tilting bolt – combined with guillotine action of the ejector – usually snapped it off like a matchstick. The most common cause of the stuck firing pin was primer perforation. By changing the shape of the firing pin, it was possible to increase the area of the firing pin indentation, which had a two-fold advantage: first, the increased area of the blow reduced the chance of perforation and sticking the pin. Even if the primer was pierced, the hole was too small to enter a portion of the pin significant enough to stick. Secondly, the larger the area of the blow, the better the chance to ignite the primer, should for some reason the firing pin strike off-center. The third advantage was the large diameter of the firing pin, increasing the service life and breaking resistance.

Another unusual (for that era, at least) mechanism was the belt-feed. In stark contrast with his own previous MG 34 where everything connected with the belt transfer was placed under the feed cover, the belt-feed mechanism of the MG 39 Rh is contained entirely in the receiver. With an ejector like the one he already planted up there, he had no other choice, anyway.

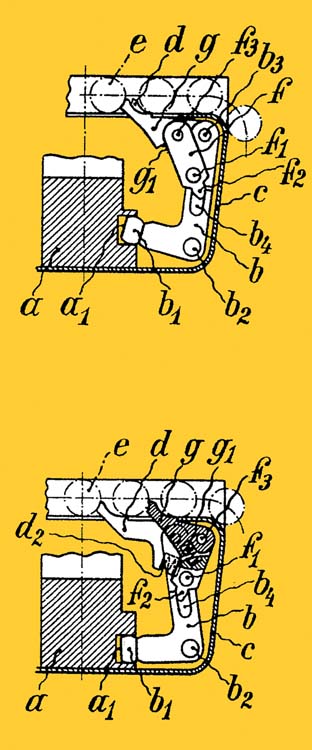

The belt-feed lever is an L-shaped one, pivoted at the junction of the prongs. The lower prong culminates in a roller, travelling within the cam path along the left side of the bolt-carrier. As the receiver reciprocates, the flattened ‘S’ shaped cam makes the upper arm of the lever oscillate back and forth in a plane perpendicular to the bore axis. On top of that lever a spring-loaded pivoting feed-pawl is placed. As the bolt-carrier recoils, the cam paths forces the lower arm down, causing the upper arm to move right (inwards) and the feed pawl drags the belt by one link, centering the fresh cartridge on the feed path. As the cartridge transfer is complete, the belt retainer pawls forced down by the sliding case snap up again to keep it from falling back, and a two-pronged cartridge pressure plate placed inside the feed cover forces it down the feed slot, into the bolt path. The cartridge pressure plate is not spring-loaded – it is stamped out of a leaf-spring steel and riveted into the feed cover.

As the bolt-carrier counter-recoils, or is released from the sear by the trigger, the cam-path along the carrier forces the upper lever outwards. The feed pawl on top of it is pivoted and spring-loaded, so on the outward stroke it folds out of the way while pressed against the fresh cartridge in the feed way, and snaps back behind the next cartridge. The whole of the belt feed mechanism is encased inside the receiver projection on the left side of the gun.

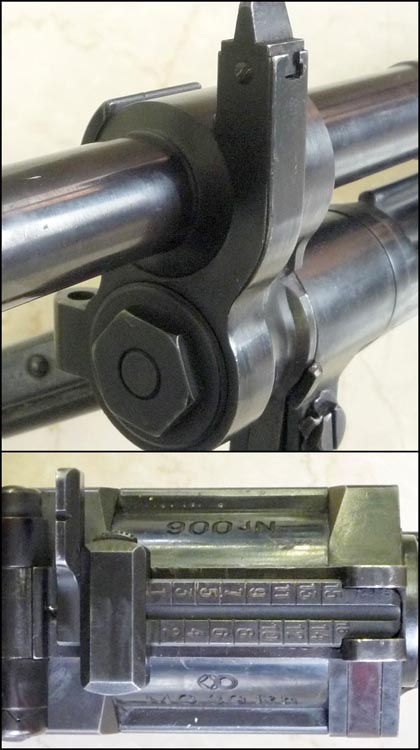

Barrel Change

The MG 39 Rh has a quick-change barrel, enabling rapid exchange when heated. The barrel latch, as in most other QCB designs of the era – again including the ZB-26 – was using the interrupted thread principle. The difference is, that in the German machine gun one has to insert and rotate the entire barrel, while in the Czech design it’s only the barrel retaining nut that the gunner had to rotate upon insertion of the spare. This overly and unnecessarily complicated the design, forcing to thread the barrel socket in the barrel mounting block. It also tends to complicate the gas chamber design a great deal. In the ZB-26 and all other gas-operated machine guns, the gas chamber is pinned to the barrel and impaled on top or inserted into the gas-tube. It is a simple, time-honored solution, though unfortunately the barrel has to be fastened by some kind of a bayonet joint to remain strictly in-line at all times during the change. In the MG 39 Rh, the price of originality was the “insert-then-turn” barrel change, resulting in an inherently leaky gas chamber. Of course, the machine gun gas chamber is not a bathroom heater and would never be gas-tight – the entire purpose is to bleed the gas off after it is used to propel the piston, but the key phrase there is “after.” In the MG 39 Rh, much of the gas is leaked out serving no purpose whatsoever.

The changing of the red-hot and swollen barrel that has to be twisted-off (if only by several dozen degrees) spawns more troubles still. The weapon has to have a change handle stout enough to withstand repeated banging on it in order to rotate the swollen barrel – and at the same time temperature insulated to save the gunner’s hand from blistering heat. In the MG 39 Rh, the barrel handle is a C-shaped affair, very stout, made of two stamped steel halves riveted, and fitted with a wooden handle.

The whole affair looks almost like the AR-10 transfer handle, and would it be placed closer to the point of balance, it could serve as a transfer handle for the whole machine gun, as the barrel itself wouldn’t rotate out of engagement, being held by a spring-loaded latch on the right.

The rotating barrel and lack of gas-chamber rigidly placed on it, although can be now held as a predecessor of the “free-floating” barrels we do worship now, had another drawback – the sights placement was unusual to say the least. Although there was no magazine well on top of the gun, it still had the sights offset to the left. The leaf rear sight was centered on top of the barrel mounting block and quite conventional except that the actual sighting notch was placed in a long holder offset to the left. The front sight was also quite conventional in appearance but placed on the left side of the wide U-shaped barrel opening of the gas chamber, permanently fixed to the gas tube.

Stange’s Lost Gun Legacy

Stange’s MG 39 Rh might have been lost for decades, but that doesn’t mean its design features were left to rot on the vine. The pivoted joint of the gas piston with the bolt carrier at once resembles that of the PK/PKM series, an impression further strengthened by the comparison of their belt feed mechanisms. But the PK/PKM belt-feed, although showing a surprising number of common points, is somewhat changed: the belt stops were replaced to the feed cover and the L-shaped feed lever is governed by the bumps along the bottom of the bolt carrier, and not the cam-path in its side. Looking for a complete copy of the Stange’s belt feed, one should compare it with another Warsaw Pact GPMG, the Czech UK vz.59.

Designers from behind the Iron Curtain usually had good taste in choosing features to copy – and so it was in this case as well: the belt-feed and piston pivot were really the most promising (one could even say: ‘the only useful’ or even ‘the only redeeming’) features of this long-forgotten, but nevertheless interesting gun. Perhaps the most fitting commentary by Louis Stange himself was his next gas-operated automatic weapon, the FG-42, which he chose to base on the 30 year old Lewis gun rather than his own design, just two years old at that time…

Caliber: 7.92mm x 57 Mauser

O/A length: 1,185 mm

Sighting radius: 407 mm

Sight: Leaf, 100-1,600 m in 100 m increments

Barrel length: 599 mm (660 mm with flash hider)

Barrel weight: 2.29 kg

Empty weight: 9.58 kg (incl. bbl)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V14N2 (November 2010) |