Story & Photography by Dudley Biddison

This author remembers in the late 1990s devouring a fledgling publication that was discovered in the guns section at Borders: Small Arms Review. Twenty years later he’s convinced Small Arms Review is the perfect vehicle in which to “educate” gun lovers everywhere.

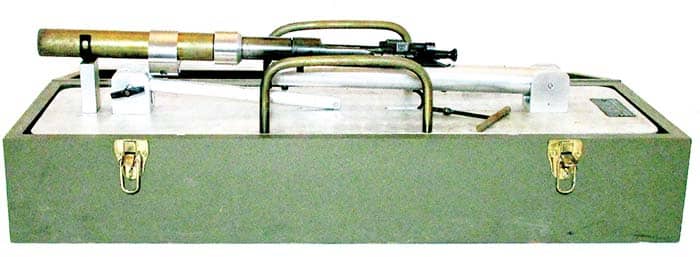

Having acquired more than a passing knowledge of firearms and weapons in general, the author had never heard of Robert Kent or his Battery. The writer’s “education” commenced after purchasing Item #117–Tools & Hardware CMPTS: at a government auction located at DRMO, Fort Belvoir, VA, in August 1992. This lot of “tools & hardware” was jammed into a 4x4x3-foot wooden crate. Back in his warehouse (used machinery dealer) over the next couple of weeks he emptied the crate and discovered a variety of fasteners, hardware and a hodge-podge of related stuff. But lying at the bottom of the crate was a 55-pound 3ftx1ftx 7in object wrapped in five or six layers of banded cardboard. How often does a 46-year-old man experience the thrill of unwrapping that special present on Christmas morning? Ta-Da! Robert Kent’s Kent Battery. The “genius” that he is, the writer knew it was a Kent Battery because screwed to the lid of an olive, drably painted wooden box was an engraved tag: “KENT BATTERY Ballistics Research Laboratories Aberdeen Proving Ground Maryland!”

Contents of the Find

Kneeling in the cast-off cardboard in front of the box, unlatching and opening the lid and peering in prompted a dumbstruck look to gradually appear on this writer’s face, and, yes, while scratching his head, he muttered, “What in the Hell’s this?” The case contained the strangest looking 03 Springfield rifle he’d ever seen. The rifle buttstock (a machined piece of 1 ½-inch round aluminum bar stock) was hinged to one end of an engine-turned-aluminum-plate with the barrel supported by a spring-type clamp at the other end. The same “KENT BATTERY” tag was riveted to the buttstock end. Two fabricated brass lift handles were attached to this base plate, facilitating removal from the box. The firearm could then be raised and supported at an approximate 30-degree angle with an aluminum rod. This rod was also hinged to the plate and fastened (3/8-inch diameter x 4-inch long brass rod brazed to a section of an Allen wrench brazed to a ¼-inch Allen head bolt) to a stainless steel compression clamp surrounding the barrel. There was no trigger guard, and the bolt handle had been modified. Threaded into the receiver was a 2 ½-inch long piece of solid stock, replacing the original Springfield barrel. Then appeared a 1½-inch long, stainless adaptor that married a 9½-inch long section of 1½-inch diameter brass tube to the dewatted barrel. The tube displayed a strange looking 2 groove rifled 1-inch bore. The crown was stamped, “1 in 10” and “1 in 15.” The Springfield’s serial #3275540 suggested, and later verified, that the Battery was assembled in 1942.

Nestled around the Springfield he found five projectiles: 1) 43/8-inch long aluminum body with a steel point; 2) 3½-inch long projectile with an initial ¾-inch steel base and the remaining aluminum; 3) 6-inch long projectile with an initial 15/8-inch Plexiglas base, then 2½-inches of aluminum and finally a 1¾-inch steel point; 4) 9¼-inch long Plexiglas body with a 3½-foot steel point; 5) The coolest of all—a 10¼-inch long aluminum rocket “look-a-like” with shaped fins that would induce spin. The “rocket” would be slipped over the barrel instead of inserted. The first 4 rounds presented lugs or tabs, engaging the riffling and inducing spin.

The wooden case had a hinged top and pair of lift handles. Two stainless steel rods, found with the projectiles, would be placed into pockets routed in the sides of the case allowing the Battery to rest flush with the top of the case when open. The Kent Battery rested on the rods in firing position.

An “Ah-Ha” Moment

When the Kent Battery was removed from the case for the first time the “Ah-Ha” moment arrived. Laying underneath the base plate was the paperwork:

1) A mimeographed copy of a letter from Lt. Col. Donovan F. Burton to Col. Charles Ostrom. The letter was dated December 9, 1965. Col. Donovan, an Associate Professor at the Department of Ordnance United States Military Academy West Point, New York, requested information. Twice a year the Col. operated “an in-flight ballistics demonstrator called the Kent Battery to illustrate projectile stability” for the cadets. He sought “design parameters of the gun tubes to insure that we do not exceed the design stresses.” Col. Ostrom was assigned to the Ballistic Research Laboratories Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland.

2) A seven-page mimeographed copy of a letter from the Ballistic Research Laboratories to Col. Burton. The letter is dated December 20, 1965. It contained a wealth of information regarding the history of the Battery, its practical application and a lesson plan titled, “Exterior Ballistics Kent Battery Demonstration Dept. of Ordnance Lesson No. 34.”

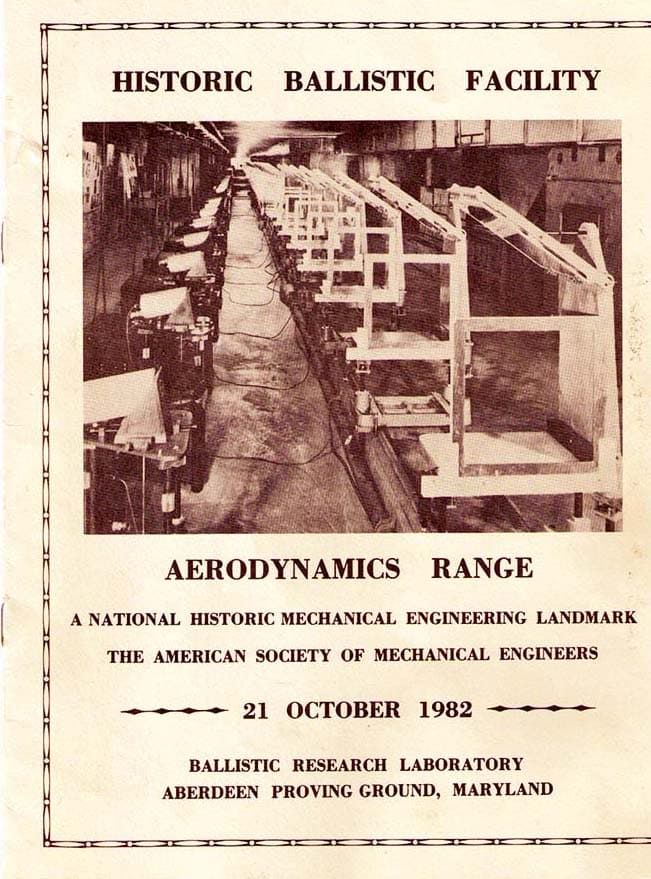

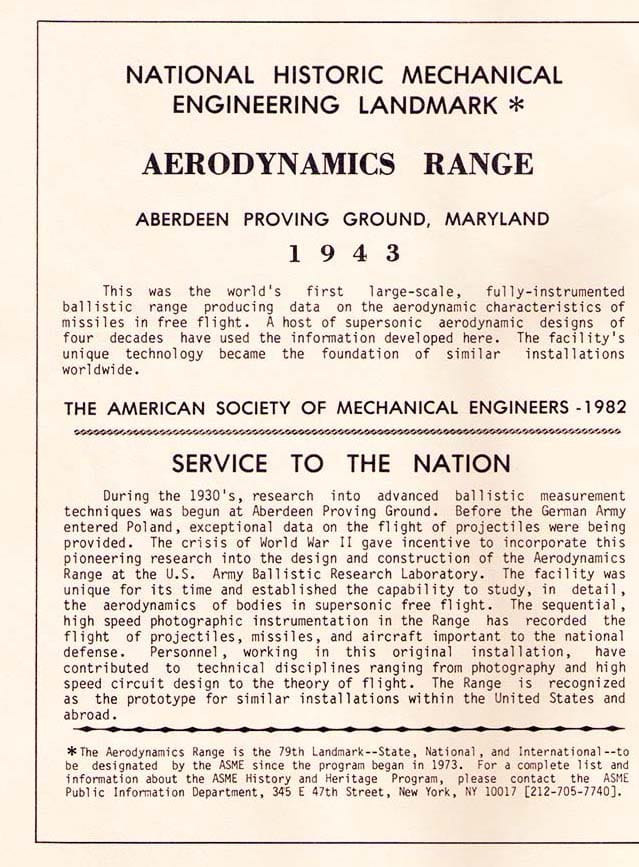

3) An October 21, 1982, eight-page pamphlet designating the Aerodynamics Range at Aberdeen a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark. Robert Kent and Dr. Alexander C. Charters “developed the technology which laid the groundwork for the design of the Aerodynamics Range.” “The Range is recognized as the prototype for similar installations within the United States and abroad.”

The writer considered this “find” moderately interesting, but since Google didn’t exist in 1992, and since he was no machinist and couldn’t fire the Battery due to the lack of a functioning barrel, his interest waned and ultimately ceased. The case was unceremoniously shoved under a section of pallet racking in the shipping area of his shop. Over the next 10 years or so it languished there; although more than once pulled out, serving as a stepping stool.

Eureka!

Somewhere in the late 90s the writer was on the phone with Mike (who manufactured custom barrels). Mike was discussing the purchase of a Gorton milling machine. The conversation drifted to a cannon barrel bore scope that Mike had bought and then on to the great stuff at the Aberdeen Proving Ground Museum. The writer began describing the odd looking rifle in the box with the neat projectiles, when Mike blurted out, “You have a Kent Battery?” “Yep. How did you know?” Mike had studied Robert Kent and the Kent Battery in a ballistics course at school.

Time passed. The writer moved to an adjoining state. Google was invented. He discovered information on Robert Kent, but the Kent Battery? Forget about it. “Robert Kent developed the Kent Battery.” No description, no history, no photo or even a drawing. He begins to realize that this box that had resided under the pallet rack probably contained something of importance.

In 2010 the writer contacted Ron, a friend of a friend. Ron worked at Aberdeen from the late 60s to his retirement in the early 2000s (“The best job a guy could ever have”). Ron was familiar with the Kent Batteries. Aberdeen owned about a half dozen, each displaying a different rate of twist. A couple sported the original wooden buttstocks, and others were mounted on aluminum plates (not engine-turned), but all were “crude” compared to the West Point Battery. Ron assumed that he was aware of all that existed but admitted that he had never seen the West Point Battery. He asked the writer if the bore looked strange, and he received an, “It sure does.” “Each barrel was machined with two different rates of twist—the West Point: 1 in 10 and 1 in 15.” Ron reminisced about firing various banks of batteries in projectile flight demonstrations up until the mid-1970s … about blanks misfiring causing the projectile to “plop out” and travel 10 feet … about using a cartridge containing the incorrect charge causing the projectile to travel twice as far as it should … about filing nicks and removing dents when a projectile landed where it shouldn’t. “It was great fun,” Ron said. The demonstrations ceased, and the batteries disappeared. Only a couple of people had ever seen the Kent Battery in person.

A Trip to the Gun Store In 2016, this writer met Bud, a gun collector in his late 70s who ran a great gun store nearby. Having never met Bud beforehand, the writer walked in cold off the street and asked him if he would like to see something really neat. Bud thought at first, because of size of the case, that it contained some type of LAW launcher. The case was opened, the Battery was lifted out and placed in the firing position. The projectiles were arranged in front, and the documents produced. You’ve all seen it, and we’ve all done it. Bud examined Kent’s creation, cycled the action and held and admired each projectile. He scanned the documentation in order to understand what was before him. His son was then called and told to “get over here now!” The same procedure repeated. With a gleam in his eye, Bud then telephoned a good friend and began the conversation with, “I’m looking at the most beautiful firearm that I’ve ever seen.” Later during the visit Bud murmured, “What in the world could this be worth? $3000, $30,000, $300,000, $3,000,000. Who knows?”

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V23N5 (May 2019) |