By Michael Heidler, All Photos: Springfield Armory NHS

As the fronts hardened in World War I and little progress was made in trench warfare, the heroic bayonet charges showed less and less success and led to high losses. All sides were looking for new solutions to regain momentum.

The United States had long hesitated to intervene actively in the hostilities of World War I. As the conflict continued to escalate, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) were formed in France on 5 July 1917, under the command of then Major General John J. Pershing. The first of the so-called Doughboys landed on the European mainland in June 1917. But Pershing insisted that his soldiers be well trained before they boarded ships. As a result, few troops arrived in France before January 1918.

Initially, four combat-ready U.S. divisions under French and British command were deployed to gain initial front-line experience by defending relatively quiet sections of the front. Initially, the equipment used also came from French and British stocks. Meanwhile, in the United States, resourceful tinkerers and engineers were searching for new and better weapons to give their soldiers an advantage in battle.

The Gas Service Section of the U.S. Armed Forces had a curious idea for increasing combat effectiveness: a kind of miniature flamethrower on the rifle was intended to cause the enemy to take flight in fear when attacking their positions. The development went under the name “Flaming Bayonet.” While work was still in progress, the Gas Service and Chemical Service departments were merged to form the Chemical Warfare Service (CWS).

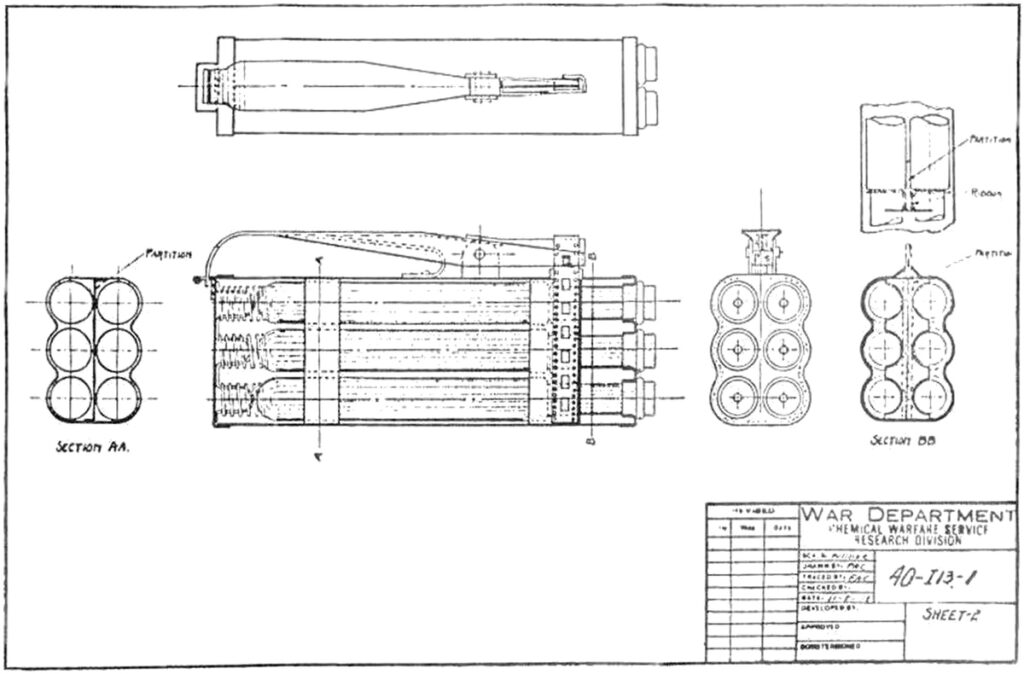

The Flaming Bayonet was a square sheet metal container with six flame cartridges, three in each of two rows. Initial tests with liquid fuel had to be abandoned because of the danger to the shooter from leaks and difficulties with firing or spraying. Therefore, they switched to cartridges filled with powder. In front-line operations, these would have been much safer to handle and easier to transport.

The container was attached to the bayonet lug from below with a connecting piece when the bayonet was mounted. On both sides of the connector were two spring-loaded pushers that clamped the container in place. It could thus be easily removed and replaced. On its upper side was a metal bracket as a trigger, which was secured by a cotter pin with a ring.

After pulling the cotter pin, the shooter could operate the trigger. To do this, he gripped the rifle with his second hand at the front of the stock above the receiver, as in bayonet fighting. This allowed him to aim the weapon at the target. With the edge of his hand, he then pressed down the trigger and the fireworks went off.

Unfortunately, it is not known exactly how the system worked. It is not clear from the few surviving documents whether all six flame cartridges were activated simultaneously or somewhat delayed one after the other. The former would give a greater fire spell, the latter a longer lasting fire. According to the drawing, individual activation of each cartridge as needed does not seem to have been possible. It is also not known whether the device could be refilled on site or whether this had to be done at the factory.

The official designation was “Flaming Bayonet, Cartridge Type, Mark I”. The weight is given as 285 grams (5/8-pound). Depending on humidity and wind direction, the flame length was between 5 and 15 feet. That is about 1.5 to 4.5 meters. The few available photos of tests show the device mounted only on a rifle U.S. Model 1917. However, it could easily have been adapted to other rifles by altering the connecting piece.

Old but undated notes state that a consignment was shipped to France. However, there is no evidence of this, and no surviving specimen is known to date. Why the development finally came to nothing can probably no longer be explained.

However, the head of the overseas division of the Chemical Warfare Service, General Amos A. Fries, was an avowed opponent of incendiary weapons of all kinds. He saw them as completely useless. Even of flamethrowers, he wrote after the war that they were, “one of the greatest failures among the many promising devices tried out on a large scale in the war,” and one could simply duck under the flames. Fries relied entirely on poison gas and pushed developments in this direction.

Under a leader with this attitude, it is not surprising that the flame bayonet was not given a future. Whereby – based on the photos, the whole thing looks impressive. But would an opponent who had already survived weeks or months of barrage and all kinds of horrors really have been impressed by it?