The U.S. Army Ordnance Museum Established at Aberdeen Proving Ground

An article in the November/December, 1971 issue of Ordnance, published by the American Ordnance Association, records prophetically that the Ordnance Museum at Aberdeen Proving Ground, established in 1919 [and] raided for scrap metal in World War II and again during the Korean conflict has a history of struggle.

1927: Jarrett Joins the Reserve Army – the Aberdeen Museum Opens

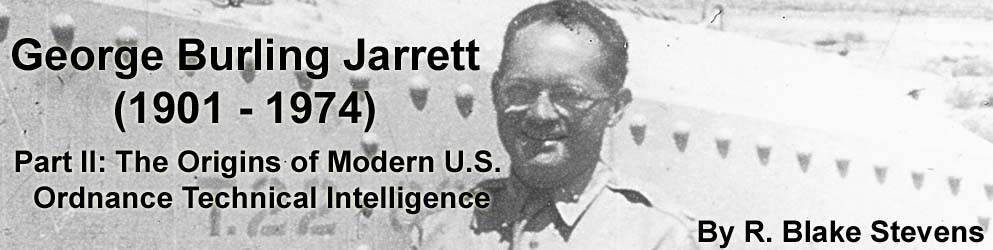

An article published in the Harford Democrat on April 14, 1966, to commemorate then-Colonel George Burling Jarrett’s retirement as Curator of the Ordnance Museum at Aberdeen Proving Ground, records that Jarrett was commissioned in the U.S. Army Reserve in 1927.

A later article in the same newspaper, published on April 4, 1973, titled A New Museum to Open, records that the original Ordnance Museum at Aberdeen was officially opened in that same year, 1927: Although it had been in existence for seven years prior to that time, the museum was housed in a rectangular metal building which had been manufactured in France. This structure was utilized by the Army for a time following World War I. It was then dismantled and shipped to the Proving Ground for reconstruction and use as the post museum.

WWII Breaks Out in Europe – Jarrett Ordered to Active Duty

The draft of Jarrett’s own May, 1970 article continues to chronicle his first visit to “the real” Aberdeen, and then, as the new war became a reality, his growing involvement with the Ordnance Department:

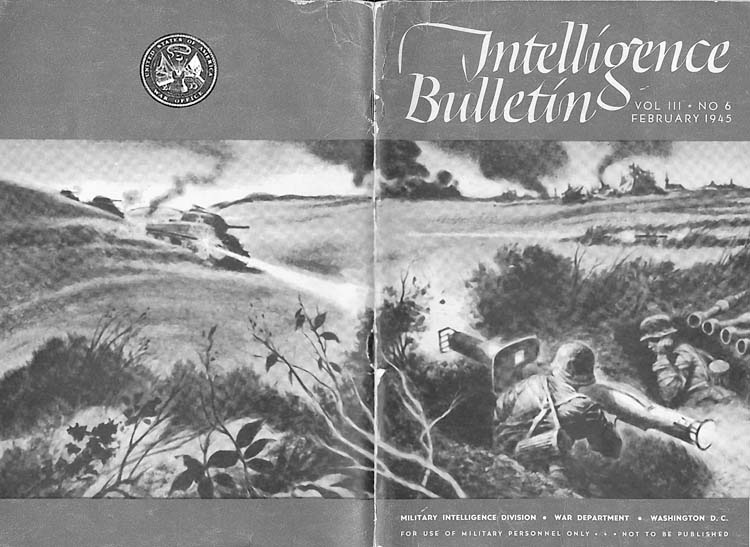

I had gone to Aberdeen Proving Ground as early as 1924 to see the famous Ordnance Museum which was a display made from World War I captured materiel. They had a fine collection of tanks, artillery, various artillery ammunition and bombs, and some of the more important small arms.

The 1938-39 period was full of a new war threat, as Hitler did as he pleased in Europe. Then, in the late summer of 1939, war did burst on Europe. This caused an alert in the U.S. and, having been a reserve officer since 1927, I was invited by Colonel Hatcher (later Maj. Gen.) to join his staff at the Ordnance School then being expanded at Aberdeen Proving Ground, long a Mecca of Ordnance as far as I was concerned. I closed up all my display activities, built a series of sheds at the farm, and stored all my collections. Then in November of 1939, I went to Aberdeen and joined Colonel Hatcher.

In 1939 when I joined the Staff and Faculty of the school, I was also given the added duty of Curator of the Museum.

Since teaching about small arms, artillery and or munitions was very much the same as I had been doing with my own museum displays, the teaching-lecture job as a staff and faculty member at the Ordnance School was just a continuation of my former work. There was one important difference, however: this time, this knowledge could be of use to our Ordnance Program in the mobilization of the Army.

Col. Icks’ 1974 article in the Ordnance Journal continues the story by describing some of Lieutenant Jarrett’s early accomplishments after joining the Ordnance Department in 1939:

[Jarrett] was among the first few reserve officers in the United States to be ordered to active duty early in the period preceding Pearl Harbor, and the first reserve officer to become a member of the staff and faculty of the Ordnance School at Aberdeen Proving Ground. In 1939, the late Major General Julian S. Hatcher (then a colonel in command of the school) requested that Lieutenant Jarrett be ordered to duty at the school… Lieutenant Jarrett’s background and interest caused him to be made Museum Officer. He also helped… establish a Bomb Disposal School.

Jarrett Sent to Egypt to Assist the British

Col. Icks continues:

Under Lend-Lease, the first shipload of American light tanks went to Egypt for the British in May, 1941… Since the British also were receiving other American weapons, they were in need of an ammunition expert. Jarrett, by now a captain, was ordered to Egypt as a one-man technical section to act as ammunition advisor to British GHQ.

Jarrett’s own May, 1970 draft article fleshes out the beginning of this crucial phase of his career as follows:

I was sent from the Ordnance School to General Maxwell’s Ordnance Staff in Cairo in November of 1941, which had the responsibility of helping the British 8th Army to understand and use the American Lend-Lease equipment then being furnished them… Soon I was to see all sorts of Allied and enemy materiel in daily use as the British fought the Axis armies.

I also became the Director of the USA Ordnance School, Middle East, and our job was to teach the British troops how to use the Lend-Lease equipment. These were the U.S. M3 Light Tank, called the Stuart, the M3 Medium called the Grant, the M4 Medium called the Sherman and the M7 Gun Motor Carriage, called the Priest… Up to that date I had known many of the designers in the Office, Chief of Ordnance and the proof engineers at Aberdeen who tested their designs. So I was well aware of the ordnance thinking of that august body at the time, and then being in the Middle East I was soon to examine and test many of the captured items.

With the advent of Rommel the desert warfare took on a new aspect as he certainly had fine operational plans, excellent designs in their ordnance (some of which proved sensational as the war progressed), and certainly very courageous and brave soldiers. The world was treated to a new concept of warfare and equipment as the war in the desert opened up.

To me it was apparent in 1942 that a lot of American design thinking of that period had not enjoyed that which the Germans had given to their ordnance. During WWII we learned quickly and made many vast improvements, but in some areas such as tank guns and armor we lagged behind, with badly-needed new designs not being available until the close of the war.

The Origins of U.S. Ordnance Technical Intelligence

An excerpt from the book Planning Munitions for War continues with an overview of U.S. Ordnance Technical Intelligence – or the lack thereof – as World War II began in earnest for American forces:

The U.S. Army’s disregard of developments in foreign munitions before 1940 is a perpetual source of astonishment to the European… the extent of what the Ordnance Department did not know about German, French and British ordnance is plainly revealed in a list of questions prepared by the Office, Chief of Ordnance in June, 1940.

At the end of August, 1940 the General Staff inaugurated an Army-wide intelligence system. The Ordnance Military Intelligence Section was established in September… From the data supplied by the special bulletins of G-2, the small staff of the Ordnance section periodically prepared detailed analyses of information bearing on ordnance. The Ordnance Intelligence Bulletins, averaging monthly nearly fifty pages, circulated among interested agencies… As early as March, 1942 the communications of the Acting Ordnance officer in the Middle East [Jarrett] described features of German weapons encountered by the British in the recent battles for North Africa, and a series of photographs of captured equipment arrived at Aberdeen soon after.

Some actual specimens of German materiel also were shipped to the States, although in 1942 they formed a thin trickle compared to the flood that was to reach Aberdeen in the summer of 1943.

Early in 1942 General Barnes was convinced that research and development would benefit by a more direct flow of technical information [and] that summer, as soon as he became head of the separate division for research and development, he persuaded G-2 and the rest of the War Department that… specially briefed Ordnance teams should be sent to the active theatres. The first Ordnance intelligence mission accordingly went to North Africa soon afterward.

The New York Times Confirms “New U.S. School in Africa”

Under the heading “Aberdeen Men Busy in Africa”, a New York Times story by-lined Cairo, May 9, 1942, reads in part:

Major General Russell L. Maxwell, head of the United States Military Mission in Africa, announced today that his organization has opened an ordnance training school for the Eastern Mediterranean area… The school is intended to train non-commissioned officers of the British armored corps in the maintenance of United States equipment, particularly tanks… Commandant of the school is Major G. B. Jarrett, formerly of the U.S. Ordnance School in Aberdeen, Maryland.

Establishing the Foreign Materiel Section at Aberdeen

A further excerpt from the book Planning Munitions for War continues as follows:

Meanwhile, Jarrett’s Finest Hour

As noted above, Jarrett went to Egypt as a captain in May, 1941, assigned as an ammunition advisor to the British Army in North Africa, where his vast knowledge of U.S. and European ordnance was to be used to its fullest value. For his outstanding achievements during this mission, chronicled in detail below, Jarrett was awarded the Order of the British Empire (O.B.E.), and the Legion of Merit.

The following long excerpts from the excellent article in the December, 1957 issue of Cavalier magazine, rather irreverently titled “The Junkman Who Stopped Rommel”, indicates that author Arch Whitehouse spent a great deal of time and care researching this crucially important period in Jarrett’s career:

Hitler’s Afrika Korps had swept across North Africa in one victory after another, and was now threatening Cairo itself. The only entrance to the city was through the back door, which the British had managed to keep open by defeating the Italians earlier in Eritrea.

That is one terrible region. The world has some bad deserts, like the Sahara, the Arabian, the Sind, and Australia’s Great Sandy, but that lifeless stretch of dead volcanoes, volcanic glass, and drifting sand between Khartoum and the Red Sea can make them all look like a fruitful paradise. To make matters worse for… Jarrett, the only desert transportation available was an aged Grumman flying boat that was definitely not made for emergency landings on sand… By the time he landed in Khartoum he had referred so frequently to his new, pocket-sized edition of the New Testament that most of his suffering fellow-passengers thought he was a chaplain.

But once he was in the land of the Nile, Jarrett felt as much at home as in his own museum. Egypt was the end of the line, but so desperate had grown the battle for North Africa that every weapon, new, old, or obsolete, was being pressed into service. Worst in the lot, according to the complaints of the British, was a lot of Lend-Lease “junk” sent over by the United States, and it was with the correction of this rather unflattering impression that Jarrett was primarily concerned.

Brigadier General R. E. Maxwell, in command of the United States North African mission, made it bluntly plain that the trouble Jarrett faced was not trivial. “I sent for you” he explained, “because I need a specialist in everything. I’m appointing you Ammunition Advisor to the British, and I must say they have a real problem. Frankly, unless something is done immediately to ‘surround’ this problem, they can lose this war right here in Africa. They are having trouble with our tanks, with our anti-tank guns, and with our ammunition. Now you know this lend-lease stuff is not the most modern equipment in the world, but when the British say they can do more damage throwing kippers at the Nazis than they can with stuff marked ‘Made in U.S.A.’ well, that’s not good, you know. Get up there to Heliopolis and find out what’s wrong.”

Jarrett’s acquisitive heart pounded when he saw the foul-up at Heliopolis. Spread out for acres were such an array of English, French, German, Italian, Russian, and American weapons, only a few alike and most of them of World War I vintage, that his collector’s soul ached to think of their being destroyed in combat. At the same time his long-subdued gadgeteer’s instinct wanted to see everything belching smoke, and with that his dander rose. If there was something pathetic about trying to pit these aging relics against Rommel’s modern, fast, heavily-armed tanks plated with shell-deflecting Krupp steel, Jarrett did not think so. These were his pets, and he knew what they could do.

Fortune favored Jarrett on his first contact with the British. Ordnance officers were puzzling over the fact that some of their men had apparently been machine-gunned with their own bullets. “The only difference,” said a major, “is that these are stamped ‘7.7’. Otherwise they are identical to our .303 ammunition.”

Jarrett hefted the [cartridge case] and peered owlishly at its [headstamp]. “Easy”, he said. “In World War I you British supplied the Italians with Vickers and Lewis guns, and .303 ammunition to match. They ran out of ammunition long ago, but with the guns being as good as ever, Mussolini just ordered more of the same ammunition from his own munitions factories. Everyone knows that in the metric system, 7.7 is the same as .303 in British inches.”

“They do?” Somewhat dazed, the British major looked at Jarrett with new respect.

“Of course, these did not come from your guns,” continued Jarrett as though he were lecturing in his museum. “These came from an Italian Fiat machine gun. Every weapon leaves its own particular identification on…”

“We know that, but in this man’s war there are hundreds of different kinds of weapons. We’d have to set up a Scotland Yard here to identify them all.”

“Not at all,” said Jarrett modestly. “I know every single one.”

“… Now what’s your biggest problem?” asked Jarrett.

“Those lend-lease 75mm shells of yours” said the colonel in command. “At long range, with a high trajectory, they work fine on a stationary target. When they come bang-on down on the nose, they are quite satisfactory, but it so happens we did not order them for that. We need them against tanks, and I must say I take a dim view of their performance there.”

“Tell me exactly what happens.”

“Nothing, dammitall. Not a dashed thing. You must know these tanks are fast. You shoot ’em like you shoot rabbits with a shotgun. Figure out the range, lead ’em a few feet, and blaze away. Hardly proper for artillery, shooting from the hip, as it were, but this war is hardly proper from the beginning. Now here’s the thing in a nutshell – at a flat trajectory, your shells bounce off those tanks like peas, and when they explode, if they explode at all, it’s when they ricochet into the ground a mile or so beyond. I will say this for the Heinies – they hang their armor plate on their tanks at so many angles that it is almost impossible to score a direct hit.”

The two months Jarrett had spent exploring the secrets of the French “75” fuse raced through his mind. The word was “creep”. Those World War I fuses were so sensitive that the mere brushing of a shell through the treetops was enough to jar the “creep” into sliding up to detonate the charge. The Americans, vexed at so many premature bursts, had taken the creep out of their fuses, and were gratified thereafter when the shells exploded only upon making direct, nose-on contact with the target. That was fine when all artillery targets were stationary, but for World War II, against racing tanks, that old creep or “graze” fuse could be mighty handy. Even though a shell only kissed an angled plate of armor, it would explode fast enough to rattle a few teeth.

“The last of the creep fuses were made in 1918,” announced Jarrett from his stockpile of obsolete knowledge, “but if I know the French, they did not throw away the surplus of old fuses when the new models came in. Aren’t there a lot of French Foreign Legion outposts around the Sahara somewhere?”

The British colonel had not achieved his rank through being dim-witted. “Better yet, old chap”, he announced. “A lot of the French forces from Syria have joined us, bringing in their old French “75s” with them. Seemed a little hopeless at the time, but now that you mention it, our RAF blokes can fly you up to their encampment in a couple of hours.

Within 24 hours of his arrival, Jarrett had master-minded his first triumph. At the French encampment he located a store of 90,000 “creep” fuses, No. 1898/09, and had them airlifted back to Cairo. It marked the turning point. With Rommel within 90 miles of Alexandria on his “unstoppable” drive, the Tommies went into action with the Jarrett-improved shells. It was a slaughter. On modern shells the old museum-piece fuses, some of them dating back to 1915, acted with uncanny assertiveness, needing, as one Tommy said, “only a whiff of sauerkraut to go boom.” The supply lasted all through the Libyan battles the following May, and Egypt was saved.

Meeting Major Northy

At length [Jarrett] came to an ammunition dump, and there, leaning disconsolately against a mound of captured shells, he met a Major Northy, ammunitions expert with the Australian forces. Instinctively Jarrett looked first at the shells.

“High explosive ammunition used in the 7.5cm tank cannon of the Panzer IV,” he catalogued aloud.

“Righto,” agreed Major Northy. “And what bloody chance do we have with our pea shooters when the Jerries have got ammo like this?”

“But they haven’t got this pile,” observed Jarrett, blinking. “We have. Let’s toss it back at them.”

“Wrong size. I suggested once that wars be fought with interchangeable ammunition, but nothing ever came of it.”

Jarrett measured the shells with nothing more scientific than his eye. Except that the rotating band looked a little thick and wide, he had just the gun to fire it. “The old M2 tank gun,” he mused. “Frankly, I’ve always said the tank and the gun were better than their ammunition. If you don’t mind, this is my chance to prove something.”

Major Northy could see no reason why he should mind. An hour later they were in Cairo requisitioning an old engine lathe from a British-owned machine shop. It was not self-powered, but that little detail meant nothing to Jarrett. Back in his junkyard he had enough old trucks, belts, gears, and other incidentals to power a dozen machine shops. By mid-afternoon of the next day his borrowed lathe was hooked up to the drive wheel of an old truck, and a crew of mechanics who knew better but didn’t give a damn were busy trimming the rotating bands of the captured shells to fit the M2 tank gun. Among the minor miracles of the war is that not a single shell exploded while being spun furiously on the lathe.

Out on the Suez Road Test Range, even Jarrett was surprised at the results. In its native German gun, the captured ammunition had a muzzle velocity of 1,650 feet per second: in the M2 gun it blasted out at 1,950 feet per second, with an increase in its power to penetrate that was truly fantastic. When tested on a captured Panzer tank, it not only pierced the armor plate, but with its high explosive burst it scattered the tank over the desert.

“Wow, that’s better than our best ammunition,” exclaimed Jarrett, picking up a twisted chunk of “invulnerable” armor plate. “Back in Aberdeen there’s a big argument about armor-piercing shells. One group claims the shells have to be high-explosive to do any real damage, and the other says a standard charge is plenty. We can settle that little debate right now.”

Another Panzer IV was rolled out onto the range, and this time Jarrett let the tank have it with the latest M61 shells. The penetration effect about equalled the German ammunition, and while there was little doubt that the shell would knock out the tank crew, the tank would be in fine shape again after a few repairs, this was the proof Jarrett wanted. The shells had to be high-explosive to decisively knock out a tank.

“That does it. I’m sending a cable to Aberdeen tonight, and we’d better get a photographer out here so the boys can see for themselves the difference in the damage. This is going to change a lot of thinking back home.” said Jarrett.

“Back home?” exclaimed Major Northy. “It’s changed a lot of thinking right here. Let’s get those 15,000 captured shells processed!”

Within another 24 hours the British Royal Armored Ordnance Corps had a score of lathes in operation, all patterned after Jarrett’s original model and powered by old trucks.

With that operation in high gear, Jarrett started one of the weirdest and potentially the most dangerous munitions operation in the world. Calling upon his wide knowledge of explosives, fuses, and shell cases, he began turning out a hybrid ammunition made up of a little bit of everything. With the Ordnance Corps improvising shell pullers and crimpers, and with Arabs for labor, he began taking shells apart for their assorted parts. American M72 and Mk I high explosive shells provided the primed cartridge cases and charges. German shells were pulled and their cases disposed of. And then, to get the desired velocity of 1,950 feet per second, all sorts of recovered gunpowders were carefully weighed, dumped into cleaned oil drums, and there blended under the hot desert sun with wooden paddles. At one point in this safety-last operation, with Jarrett himself stirring up a barrel of powder with an oar, it is estimated enough propellant was being mixed to blow the whole junkyard into bits should so much as a small spark be struck on one of the steel drums. And there was no shortage of flint-like rocks being kicked around. But the inevitable never happened, and when the hybrid shells went into action they performed so far beyond anything yet on the field that Jarrett was awarded the Legion of Merit medal.

Augmenting British Weaponry

By that time he was deep in his next task. Rifles and all sorts of small arms, plus ammunition, were in desperately short supply. In his dash across North Africa, Rommel had made a point of striking first at supply depots, and by the time he had the Tommies backed up against the Pyramids, most of them were reduced to the few weapons they had been able to carry with them, and the few rounds of ammunition that remained in their belts. What was more; the wily Desert Fox had done an excellent job of severing all their supply lines. Rising to this crisis, Jarrett recalled the stacks and stacks of Italian materiel he had seen during his brief stopover in Eritrea. Included had been thousands of rifles piled up in the open, and slowly being covered with drifting sand.

The admiring British at this stage were willing to grant Jarrett anything he asked for; knowing in advance few of his requests would be either sane or reasonable. They were not surprised then when Jarrett called from the Eritrean Service Command, requesting an Alfa Romeo automobile assembly plant and a score of machine shops left over from Mussolini’s Ethiopia campaign. Nor were they surprised a few days later to learn that Jarrett had cut across national lines, and that British and American armament men were working side by side in a fast-operating weapons reconditioning factory. Sand-choked weapons were being fed into one end of the converted automobile plant, dismantled, cleaned, inspected for worn parts, and reassembled at the rate of several hundred a day.

Factory organization was but a small part of Jarrett’s job. The captured Italian weapons were of all shapes and sizes, and in all states of disrepair. Until he got his machine shops going making spare parts, as many as three rifles might have to be dismantled to get enough parts to make one good one. All told, he found 53 types of rifles requiring 13 different kinds of ammunition, and he could only wonder how Mussolini had ever managed to defeat Emperor Haile Selassie’s spear-carrying warriors. He produced order out of this chaos by combining the useful parts of a dozen obsolete weapons to make a half-dozen efficient hybrids. For example, he found several hundred old Vickers and Lewis machine guns that had been stripped from old aircraft. The guns were useless as ground weapons, the whole firing mechanism of each weapon being dependent upon power supplied by the aircraft engine in synchronization with the propeller. But Jarrett had made them work in his museum, and now, by taking parts from other, less efficient machine guns, he was able to put them back in action, complete with a new spade-grip hand-trigger component and tripod mount.

His biggest triumph came when he reconditioned thousands of Mauser rifles and assured the British their own 7.92mm cartridge would fit perfectly. “It has to,” he informed a skeptical British ordnance man. “You might not know it, but your British Besa gun is an adaptation of the old Czech Brno, and the Czech gun was originally designed to use Mauser 7.92mm ammunition. So you see, Major, in copying the Czech gun you copied the German ammunition, and I happen to know we have plenty of 7.92mm ammunition in Cairo.”

Now for the astonishing part of Jarrett’s foray into the Eritrean junkyards. To classify all the Italian weapons and ammunition, sort them out according to usefulness, cross-breed those necessary to produce his hybrids, organize his reconditioning factory and machine shops, and start the flow of desperately needed weapons to the front, had taken just two weeks. He was back in Cairo just sixteen days after his departure, and spent the night writing a handbook translating American technical terms into British nomenclature.

Jarrett Draws Some Crucial Conclusions

As a captain and then as a major, Jarrett continued to follow Rommel’s retreat across North Africa. When he discovered German shell cases made of blued steel instead of brass, he was the first to announce that Hitler’s copper supply was nearing exhaustion. By taste and smell he was the first to discover Hitler’s motor fuel was ersatz, a synthetic substitute that would break down on a long haul. Both of these discoveries enabled the Allies to increase the pressure on the Germans at a time when such pressure would have been suicidal had Jarrett been wrong.

Jarrett Returns to APG a Light Colonel; Proceeds to “Raise Hell”

Col. Icks’ Ordnance Journal article describes Jarrett’s return to Aberdeen as a Lieutenant Colonel in charge of the Foreign Materiel Branch, where he was to remain until the end of the war:

A promotion to Lieutenant Colonel took place prior to his return to the United States to head up a Foreign Materiel Branch for testing and evaluating captured weapons. Finding no action had been taken on producing a delayed action fuse and finding that the 100 rounds of German ammunition he had shipped from Cairo had never been tested, it was characteristic of him to raise hell from top to bottom over the matter. Rank for its own sake meant nothing to him and sacred cows to him were for slaying… A few heads were weary when he had finished, but American tankers quickly were on the way of receiving something badly needed, although an entire year had been wasted through negligence.

Jarrett on the Foreign Materiel Branch (FMB)

In a document titled Ordnance Research Center General Story for Press and Newsreels dated November 26, 1943, Col. Jarrett spelled out the important mission of the center which he headed as follows:

The Foreign Materiel Branch was established in the latter part of 1942 to receive and store enemy weapons sent to the United States by groups of Ordnance Intelligence officers and enlisted men from the various theaters of operation. Directly responsible to the Office, Chief of Ordnance in Washington, the Branch’s mission includes the analysis of all materiel for evaluation and for possible adaptation of noteworthy designs into our own equipment, to maintain a collection of the available weapons and to conduct training programs to disseminate information on this captured enemy equipment.

The flow of German, Japanese and Italian weapons into Aberdeen Proving Ground has been continuous, and at the present time there are approximately 4,000 tons of enemy pieces, comprising 1,300 principal items. Results of the detailed analyses of the materiel tested here and at other stations are maintained in the files of the library together with intelligence received from Military Attachés and other overseas observers.

The Importance of Ordnance Technical Intelligence

Lt. Col. William L. Howard, the compiler of the informal book titled Technological Support of the Air-Land Battle, penned the following under the heading “Introduction and Purpose”:

My purpose in preparing this booklet was to record in picture and letter format the evolution of the U.S. Army’s Technical Intelligence Operations from about 1918 until the present. It is primarily the story of a select group of men in the Army who have defied the traditional career patterns and forged ahead into the future…

Certainly Col. Jarrett qualifies as perhaps the most important of this select group of men.

Jarrett in Europe, Leading a Technical Intelligence Team

Col. Icks’ Ordnance Journal article continues:

Before World War II was over, he was ordered overseas again, this time to Europe. There he participated in the industrial and military interrogation team efforts in evaluating German experimental material found in various plants and proving grounds. Again much of the material which had value to us was shipped to APG for further study and comparison…

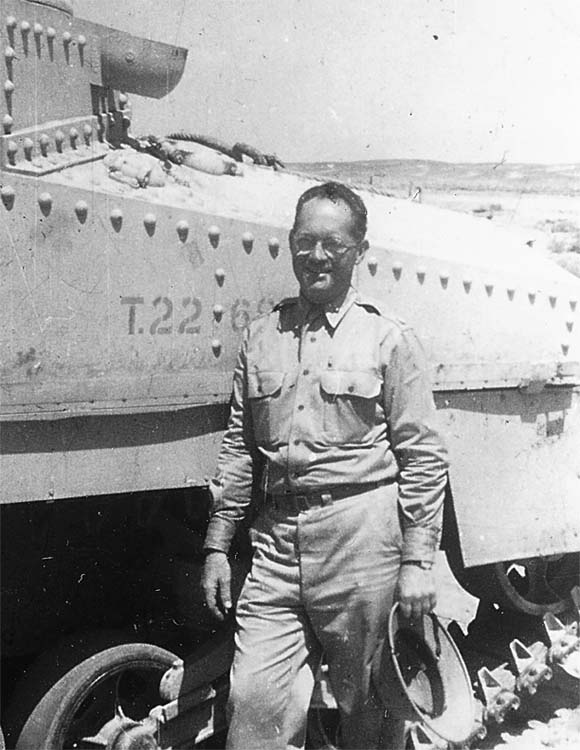

An Excerpt from Intelligence Bulletin Vol. III, No. 6, February, 1945

Tom Nelson recalls that Col. Jarrett, along with Phil Sharpe and other noted U.S. ordnance experts, gathered and edited the material which appeared in the Technical Intelligence Bulletins, published by the Military Intelligence Division of the War Department, which proved of great value to the Allied cause.

In a related article about captured WWII Japanese aircraft being tested by U.S. Technical Air Intelligence, reprinted in Lt. Col. Howard’s book titled Technological Support of the Air-Land Battle, author Robert Mikesh leads off with these sardonic words:

“The Germans fought for Hitler, the Japanese fought for their Emperor, and the Americans fought for souvenirs.” This was the comment most often repeated by members of the Technical Air Intelligence Units, whose first responsibility was to keep G.I.s away from captured enemy equipment.

This sentiment was echoed in an article titled “Ordnance Intelligence Teams Uncover Technical Secrets”, published in February, 1945 in Vol. III, No. 6 of the Intelligence Bulletin, excerpted as follows:

“One of the biggest difficulties that Ordnance Intelligence Teams face is the continued refusal of combat units to recognize the importance of technical information gained from a study of enemy ordnance.”

… This report [from a lieutenant in charge of an Ordnance Technical Intelligence Team now operating in the Pacific] emphasized an unfortunate condition which has existed for a long time. Combat troops, preoccupied with fighting or souvenir hunting, are unaware of the part captured enemy equipment plays in the progressive development of our own weapons, and of its usefulness in enabling intelligence officers to predict the probable widespread use of new weapons by enemy troops.

This difficult master-minding is a job of the Army Service Forces Equipment Intelligence Service Teams. These teams include trained personnel from each technical service. Specifically, where weapons are concerned, it is a job for Ordnance Technical Intelligence, which must keep the army up to date in this highly technical aspect of warfare.

Early in the war, the U.S. Army saw the necessity for immediate first-hand technical observation, and in December 1942 the first Ordnance Intelligence Team, a handful of specially-trained officers and enlisted men, was dispatched to a combat zone. Its mission was to procure enemy weapons and ship them to the United States to be used in a continuous study of the latest developments and trends in the enemy armament industry and to rapidly develop counter weapons. Today teams of trained technical observers work in every theater of operations.

Col. Jarrett’s Team at the Walther Factory

An interesting anecdote from Chapter One of author Fred A. Datig’s book on postwar Russian small arms, titled Soviet Russian Postwar Military Pistols and Cartridges, 1945 – 1986, discussed further in Part III of this series, concerns an important and timely visit by a U.S. Technical Intelligence team, led by Col. Jarrett, to the Waffenfabrik Walther plant shortly after the end of WWII in 1945:

… The United States Army’s Technical Intelligence team, headed by the late Colonel G. B. Jarrett, was able to enter Walther’s factory only 2 hours before the Soviets (thanks to Yalta and Potsdam) were to take charge officially. Jarrett’s group was able to cleanse the premises of the entire collection of some hundreds of prototypes of pistols, rifles and machine guns, plus much pertinent documentation, and to whisk everything, including Fritz Walther himself, away to the West.

A Typical Jarrett `Take’ on a Pentagon Briefing

Tom Nelson, who will also be mentioned in greater detail in Part III of this series, recalls a briefing which Col. Jarrett was invited to give to an assembly of general officers at the Pentagon in 1946. Casting his eye about the thousands of exhibits and artifacts at his disposal in the Museum, and concerned about just what he would be able to cover in the limited time available to him, in the end Jarrett selected and took with him five items, each of which he felt represented an outstanding advance made by the Germans in WWII.

The first items he put on the table were a captured MP44 (Sturmgewehr) and an example of its 7.92x33mm intermediate cartridge. The advantages of this new weapon system were many fold, he explained: constructed very largely of plain carbon steel stampings requiring no scarce, exotic alloying elements, production of this weapon was cheap and fast, compared with a U.S. product like the M1 rifle. Even more importantly, he said, it represented the dawn of a new tactical era, one for which the U.S. had no comparable weapon or cartridge, other than the M1 carbine and its comparably weak cartridge. (History has shown that while the U.S. was to flounder along with the underfunded M14 program until 1957, the Soviets took these advances very much to heart and were soon to emulate both the German StG concept and its intermediate cartridge with the adoption of the 7.62x39mm AK47.)

The second example he laid on the table was an MG42. This fast-firing weapon incorporated the improved cartridge belt and direct feeding system, the quick-change barrel, and the recoiling “softmount” of the Einheitsmaschinengewehr (all-purpose machine gun), all features which had been introduced in the earlier MG34, which in its day was by far the most advanced machine gun in the world. The MG42 went one step further, and like the MP44 it was also made very largely of plain steel stampings, which meant that it could be manufactured five times as quickly as a comparable U.S. Browning machine gun.

The third was, ironically, a German copy of the American “Rocket Launcher, A.T., M1″, commonly known as the Bazooka, which fired a larger (3.5″) and more powerful shell than its U.S. 2.36” counterpart. The shaped charge of the larger German projectile was capable of defeating the armor on virtually all existing tanks and self-propelled guns. Jarrett urged that the then-U.S. bazooka round be increased in size and power. (Here again his remarks soon proved to be prophetic, as U.S. soldiers rushed from Japan to Korea in 1950 were to discover that their bazooka rounds bounced off the armor of the latest Russian T-34/85 tanks.)

The fourth item was a large German artillery shell, which had been made of cheap cast steel rather than as an expensive machining as were U.S. projectiles. Jarrett pointed out that the German round was thus much quicker and cheaper to make, although it produced the same degree of devastation on impact as did the machined projectile. The advantages were obvious.

The fifth and final example Jarrett piled on the table was a late-war German Panzerfaust (literally, the “tank fist”). This he regarded as being capable of improvement (as indeed it was during the final stages of the war), because the German design was a dedicated single-shot launcher which, once fired, could only be discarded. Jarrett recommended that development be undertaken to produce a similar device, but one that could be reloaded multiple times with separate grenades – exactly like the highly successful and ubiquitous East Bloc RPG, which still accounts for a high percentage of Coalition casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan to this day.

As an extremely dedicated and knowledgeable man but one with few social graces, Jarrett harangued the assembled officers with the dire prediction that if the U.S. did not recognize and copy the advances that these examples represented, the looming threat of Soviet aggression would be difficult if not impossible to overcome in the future. The days of NMA (not made in America) were over, he concluded.

Unfortunately, his forceful demeanor and the brusqueness of his presentation rubbed his august audience the wrong way, with the upshot that rather than inspiring improvements, his urgings were ignored.

Jarrett Released from Active Duty – Becomes Civilian Curator

The Harford Democrat article recording Jarrett’s retirement in 1966 contained the following brief comments regarding his release from active duty:

… Following his release from active duty in 1947, [Jarrett] continued the study of foreign materiel until the Korean War as civilian museum curator.

Jarrett on WWII Russian Ordnance

A further excerpt from the draft of his May, 1970 article contains Col. Jarrett’s typically pragmatic overview on the state of Russian ordnance during WWII and later:

Throughout the war we, along with the British, supported the Russian effort and sent Ivan boatload after boatload of equipment, fuel, various other supplies and food, and never even got thanks. But the Germans who first faced the Russian materiel and at the time easily forced the Soviets to retreat deep into the interior, later got up against some very remarkable Russian-designed ordnance. This material, in the final analysis of combat, surprised the Germans; and let us not forget that the Russian T-34 tank provided enormous support for the great Soviet offensives which eventually drove the Germans out of Russia. The Russian engineer was no fool, was brutally realistic and [was] eventually capable of producing such vast quantities of materiel, plus training of personnel, that one day Ivan drove the German armies out of Russia.

Many Russian pieces of ordnance were reliable and capable enough of excellent field performance that they were utilized by the Germans for combat replacement in the German Army. The Russian 7.62cm field gun, model of 1936, as one example, was used by the Germans in great numbers and eventually modified to improve its performance. It turned up in Libya in 1942. When I saw this piece I was deeply impressed, and from that time on I was anxious to examine any Russian piece of ordnance we could find. I was to see many of them prior to the war’s end, and again from Korea.

By the time we were involved in the follow-through for the D-Day venture in France, use of countless Russian pieces of ordnance by the Germans was found to be commonplace, and eventually we shipped a large collection of it as captured enemy materiel to Aberdeen. After the war we conducted a considerable examination of all these pieces and coupled it with reports made by the Germans (which we had captured), who had of course captured it first. Thus we managed to become well informed on all of it and its performance. When the Korean War broke out, we possessed priceless data and an understanding of the Russian equipment which we discovered was then in use by the North Koreans, including the Russian T-34 tanks equipped with the highly satisfactory Russian 85mm tank guns.

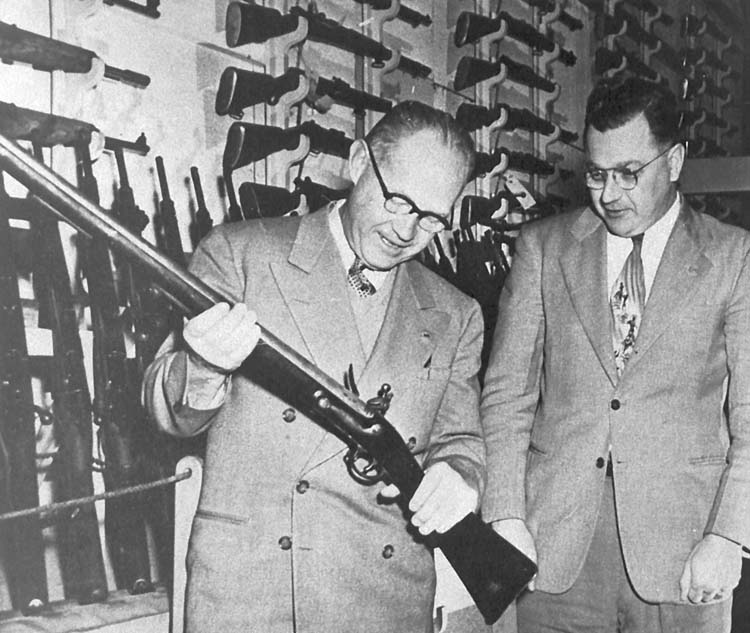

Jarrett Appointed Honorary Curator of the West Point Museum

Col. Jarrett’s friend and admirer Charles Yust, at the time the editor of the now long-defunct periodical Gun & Cartridge Record, who as discussed in Part III served under Jarrett at the Aberdeen Museum, recorded the following concerning a new accolade bestowed upon Col. Jarrett in 1952:

In the “Who’s Who” Department of our July [1952] issue, we ran the biography of Colonel G. B. Jarrett, and feel that it is in order to add a bit of new information which has recently come into our possession…

This was followed by an extract from an official letter dated November 16, 1952, signed by Superintendent of the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York, appointing Jarrett an Honorary Curator of West Point Museum:

y Dear Colonel Jarrett:

In recognition of your standing as an authority in the field of Modern Ordnance and in acknowledgement of your generous activities in an advisory and consultive capacity… it gives me great pleasure to appoint you an Honorary Curator of the West Point Museum…

It is a distinction for the Museum that it may welcome you as an “ex officio” member of its staff, and I trust you will have no objections to the recording of your name as an Honorary Curator in appropriate future publications of the Military Academy and the Museum…

A Jarrett Retrospective on the Acid Test: Combat Performance

Jarrett’s draft article of May, 1970 contains the following retrospective thoughts:

In more than 50 years of curio collecting, I have owned or cared for and tested at Aberdeen well nigh countless pieces of ordnance. Many were extraordinary, and yet many many items were well nigh worthless. Some enjoyed amazing physics lab performance and fooled people into thinking them capable of great military potential, but on the battlefield they fell far short of such performance…

It has been my privilege to observe a lot of armored force equipment in action, made movies or stills of these tests, fired their guns and shot at them to observe their armor qualities, and long ago came to the conclusion that most tanks over the years had more penalizing points than good ones. In our Ordnance Museum at Aberdeen we have had a remarkable collection of wheeled or half- and full-tracked vehicles, headed under the general title of Armor. These have come from World Wars I and II and since. Of all the collection only maybe 4 or 5 were outstanding fighting vehicles, by which one might expect to affect the outcome of WWII or of modern warfare. I’d list them as far as WWII is concerned as the German Panzer IV, with long-barrel 7.5cm gun, the Panther with its super-long 7.5cm gun, the U.S. Shermans with the British 17 pdr. A.T. gun (which the British put on the Sherman tank), the U.S. Sherman M4A3E8 (better known as the “Easy 8″on which we had put the then-new 76mm gun, and lastly the famed Russian T-34/85. All these tanks were capable of good movement and their gun performance did great hurt to the enemy, and did affect combat operations favorably for the side in question.

Jarrett Retires as Curator of the Aberdeen Ordnance Museum

Col. Icks’ Ordnance Journal article frankly sums up some of the accomplishments, setbacks and tribulations of Col. Jarrett’s remarkable career on the occasion of his retirement as Curator of the Ordnance Museum:

Before his demobilization from active duty [in 1947], Colonel Jarrett was offered a permanent commission in the Regular Army, but he decided to remain at APG as a Civil Service employee and did so until his retirement in 1966. He built up the Foreign Material Branch and the Ordnance Museum and during the Korean War played an important part in evaluating Chinese and Russian weapons and equipment in comparison with our own. A short-sighted Chief of Ordnance permitted another scrap drive, duplicating one which took place… during World War II. On both occasions, priceless museum pieces were lost forever. His own collection also suffered from lack of care while he was away. Most of the planes were in bad shape. He planned to move them to his new home on an estate near Aberdeen, but shipping costs precluded it. Eventually he sold two of the planes and most of the other weapons and moved the rest to Aberdeen.

He trained the first Ordnance Technical Intelligence team which went to Korea, but the job was then given to the Ordnance School in 1951. With fine disregard for their own part in the matter, higher authority criticized him for not having had such teams ready when they were needed. He found shortcomings in our equipment and was not reticent about letting it be known, in spite of incurring the wrath of higher-ups who preferred not to rock the boat.

He frequently got along on only a few hours of sleep a night, his usual working day being about 18 hours. His energy was boundless, and yet he was and is no recluse. With all this, he lived a normal social life with his wife and one daughter who now is married to a young Regular Army officer.

Jarrett Makes Aberdeen’s Collection “The Largest in the World”

The April 14, 1966 Harford Democrat article marking Col. Jarrett’s retirement as Curator of the Aberdeen Ordnance Museum records that “He added, from his personal collection, 9,000 items to the museum, making it one of the largest and finest collections in the U.S. Army.”

The April 4, 1973 article in the same newspaper goes further, calling the Aberdeen Ordnance Museum “the largest consolidated collection of such material in the world.”

The Ordnance Museum is Closed: Collection Moved to a Small Barracks

The Harford Democrat article dated April 4, 1973, titled “New Museum to Open”, records that the old pre-WWI French steel “Truscon” building, which had long served as the Ordnance Museum, was closed indefinitely in 1968 and the building slated for conversion into the new, modern home for the Headquarters of the U.S. Army Test and Evaluation Command.

The real reason behind this move was related to the author by long-time Ordnance expert Harold Johnson, who explained that there was a total freeze on the construction of new buildings at Aberdeen at the time, but that existing structures could be “improved”. Col. Jarrett had antagonized a number of highly-placed officers in the military by this time, and when all the possible locations for the new headquarters were surveyed, the building housing his Museum was selected. In the end the only feature that was saved was the concrete pad – the building itself was completely demolished and a totally new structure was erected on the original floor.

According to the article in the November/December, 1971 issue of Ordnance, the Ordnance Museum was thenceforth housed ignominiously “in a small, wooden barracks-type building and reduced (in terms of materiel actually on display) to a few carefully selected items and files of photographs.”

The 1973 Harford Democrat article concurs, stating that:

Despite many attempts to find a new home at the Proving Ground for the Ordnance artifacts, none were successful. It was decided to mothball the thousands of items rather than permit them to either deteriorate, be destroyed, or transferred to other installations and thereby losing the largest consolidated collection of such material in the world.

Consequently the job of labeling, recording, protecting and packing these items was begun. The larger items were moved to an outdoor area to augment an existing display of tanks, self-propelled weapons and the large field and railroad artillery weapons systems.

In 1968 the Ordnance Historical Exhibit was opened in a one-floor wooden barracks type structure. It contained a few hundred selected items, models and photographs.

Col. Icks pulls no punches in describing how Jarrett’s outspoken attitude had contributed to this public humbling of the importance of his work, and thus of himself:

It was a hard blow for this sincere and earnest man to reach the age of retirement, but an even harder blow was to have higher authority decide that his Museum Building was needed for other purposes and that all the contents should be placed in mothballs indefinitely.

This was the last job that he supervised, almost like a man attending his own funeral. After the Army reorganization which did away with the Ordnance Corps as such, APG became just one of many testing facilities now controlled by the Army Materiel Command. All the Defense experts seemed to be looking ahead and apparently saw no need to look back or even to look around to see what the competition is doing.

Colonel Jarrett fought that kind of smugness and is still fighting it. He believes with all his heart in the United States and cannot understand anyone putting personal prestige ahead of his country’s interests. Stuffed shirts are his favorite target and, as can be imagined, he has intensely loyal friends and intensely bitter enemies.

The Ordnance Technology Foundation and the New Museum Building

Characteristically, however, Jarrett bounced back. As recorded in the final excerpt from Col. Icks’ Ordnance Journal article,

… [Jarrett] did not take the placing of his beloved Museum on the shelf as final, but is working hard toward the building of an Ordnance Center of Technology at APG supported by private subscription…

The article in the November/December, 1971 issue of Ordnance continues, recording that:

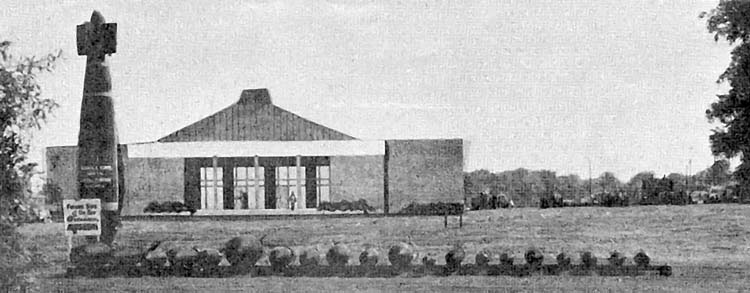

… ground was broken on August 27, 1971 [and] the new building will dominate the center of the APG’s Foreign Tank and Artillery Park… Arranged around the building will be the entire collection of foreign tanks and artillery while, inside, small ordnance items will be displayed.

The value of the present collection has been appraised at $24 million – and this tremendous treasure of armament artifacts and information has been guarded and kept together almost single-handedly by Col. G. Burling Jarrett, U.S.A. (Ret.), who, however, is the first to call attention to the help that has been received over the years from individuals and groups who have the Nation’s defense interests close at heart.

The April 4, 1973 Harford Democrat article further records that:

… six years of dedicated labor by local citizens, businessmen and both retired and active U.S. Army officers will be culminated when the Ordnance Center of Technology Foundation, Inc. donates the new structure to the Army.

The museum construction was undertaken by the foundation, a private corporation.

Museum Size, and Jarrett’s Role, Severely Curtailed

Despite his Herculean efforts, described above, which “single-handedly” guarded and conserved “this tremendous treasure of armament artifacts and information”, and then his dedication in organizing the non-profit Foundation which raised the money for the new museum structure, Col. Jarrett had meanwhile seen his future role reduced to that of a mere “adviser” to the museum.

In addition, despite the best efforts of the Foundation, which had envisaged a building of some 300,000 square feet capacity, the money raised proved sufficient only to underwrite a much more modest structure, which measures some 10,000 square feet.

A Typical Jarrett Broadside Greets Plans to Curtail Exhibits

In an article published in the April 26, 1973 edition of the Baltimore Sun, the new curator described in detail how he planned to arrange only a comparatively few exhibits in the new museum, in effect utilizing only 15 percent of the available material.

Typically, Jarrett objected strenuously to these plans in a letter to the Sun Editor, which is reprinted as follows:

Sir: I have read your article (The [Baltimore] Sun, April 1) on the Ordnance Museum with considerable amazement. You were duped into the background, for the article is not only misleading but parts are downright incorrect and could only be the work of misrepresentation on the part of the person interviewed. The picture is very distorted.

The Ordnance Center of Technology Foundation has had a difficult time over the past seven – eight years to realize this goal, and quite frankly your article at this critical time comes as a shock. That the story could be so diverted from the facts is a dreadful sham – and by one who has only personal aggrandizement as a basis for it.

[Gordon W. Chaplin] may be a good history teacher but is no ordnance expert. To condemn 85 per cent of this famous collection to stay in the warehouse by his display arrangement certainly is a dreadful shame. The current design of the display media while exquisite is exceptionally wasteful of space.

It is a great shame that your article had to appear at this time, less than two months prior to dedication… I have spent more than 30 years of effort on making that collection and creating a building and I must repeat: to condemn 85 per cent of it to the warehouse is inexcusable.

G. Burling Jarrett, Colonel U.S.A. (Ret.),

President of the Board,

Ordnance Technology Foundation.

Aberdeen.

An excerpt from a one-page In Memoriam to G. Burling Jarrett, Colonel, United States Army Reserve, Retired, records that the new museum did open as scheduled, with Jarrett himself serving as master of ceremonies:

On May 18, 1973, the completed structure was dedicated and accepted by the Army in an impressive program. Colonel Jarrett served as master of ceremonies. Until his final illness, he continued to serve as an adviser to the museum.

A final excerpt from the May 19, 1973 article in the Harford Democrat states as follows:

Thousands of historical ordnance items presently in storage will see the light of day on May 19, 1973 when the new Ordnance Museum is… turned over to the U.S. Army and opened to the public.

Priceless and historically irreplaceable, this collection represents more than a century of [U.S. and foreign] ordnance development.

A Final Tribute, to an “Outstanding American”

A letter to the editor published in the March/April, 1972 issue of Ordnance, the journal of the American Ordnance Association, titled “Outstanding Americans”, by Hanson W. Baldwin, contained the following tribute to Col. Jarrett:

I am delighted that Col. G. Burling Jarrett’s single-minded devotion over many years has at last paid off in a new building for the Ordnance Museum at Aberdeen… I well remember the days when Col. Jarrett, a born collector of ordnance of any kind, was fighting a lonely struggle for recognition of the importance of such a museum. For years the “museum” was his own back yard: only Col. Jarrett’s perseverance over the years overcame official indifference – and even opposition – lack of funds, and apathy.

The End of the Road

A final excerpt from the Harford Democrat of July 3, 1974 reads as follows:

Colonel George Burling Jarrett USAR (retired) died at his home in Churchville on Monday evening [July 1, 1974].

Col. Jarrett was Curator Emeritus of the Ordnance Museum at Aberdeen Proving Ground and his leadership within the Ordnance Center of Technology, Inc., a non-profit organization, resulted in the building of a new U.S. Army Museum at the Proving Ground. The structure was dedicated on May 18, and Col. Jarrett served as Master of Ceremonies.

He is survived by his wife, the former Marguerite Workman, a daughter, Mrs. Nancy Jarrett Travis of Oak Ridge, Tenn., and three grandsons, Michael, Richard and William Travis II.

Interment will be in Arlington National Cemetery at 1:30 p.m. [on July 5, 1974].

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V14N12 (September 2011) |