By Michael Heidler

“Spring 1941… operation makes sense only if we defeat the state in one go. Gaining of certain space is not sufficient. A stop in the winter is precarious.” General chief of staff Franz Halder noted these words after a discussion with Hitler on 31, July 1940 into his diary. When they let three million German soldiers march eastward in daybreak of 22 June 1941, Hitler and his generals believed that they could wrestle down the colossus Russia within a few months. And the first successes seemed to give them right. After the first victorious battles, Halder wrote into his diary on 3 July 1941: “It is probably not too much said, if I state that the campaign was won within 14 days.” Fears were struck into the wind. Even General Paulus found no hearing with his warnings and suffered a rebuff from Hitler: “I do no longer want to hear this prattle over troops in the winter. Feeling concerned about it is absolutely unnecessary. It will give no winter campaign.”

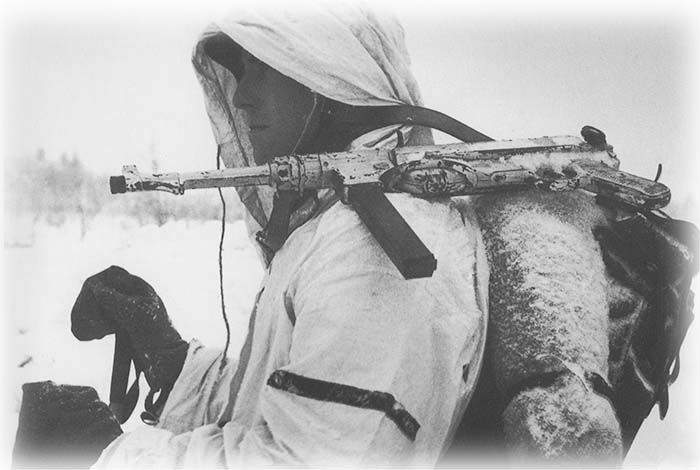

All of this had the consequence that the German troops trekked towards the east without the least preparations for a winter war. And so it came as it had to come: At the end of October the mud period began, followed by the onset of winter. Without winter clothing for the troop and without antifreeze for the engines, the dash of advance diminished. The victory, believed within one’s grasp, slipped into far distance. The homeland began to collect winter clothes, in great haste the technical designers tried to hold the war machine on running by technical improvements and the magazine “Of the front for the Front” got filled with words of advice and construction manuals for all kinds of aids for weapons and equipment. That way a lot interesting and little known accessories for hand-held weapons and machine guns were created.

A serious problem for shooters was carrying thick gloves. Often they couldn’t grasp and pull the trigger of their weapons without yanking the gloves off. As a remedy, the Bayerische Berg-, Hütten und Salzwerke-AG in Sonthofen had developed a winter trigger for the MG 34 early in 1941. It was a lever-construction that could simply be attached to the sling hole of the grip without changes in the weapon. Despite its usefulness, no standard manufacturing took place. Early in January 1943 a construction design of an only easily simplified version of this device appeared in an information magazine for weapon masters: They should build the necessary triggers themselves.

Early in November 1943, an industrially manufactured winter trigger of simplest design was officially introduced. This was formed out of a piece of sheet metal and could be attached to both the MG 34 and the MG 42. Only the two retaining split pins had to be put in slightly different holes. On 7 October, 1943, the instruction D.1868 was issued: “Instructions for the winter trigger machine gun 34 and 42.” The only known manufacturer is the George Sindermann works in Mallmitz/Schlesien (secret letter code “chs”).

Although the device proved well, there was still a lack of means to turn it off: It often jammed in the pressed position when shooting and the MG continued firing after releasing the trigger (a runaway gun). The firing of short bursts was hardly possible and the endangerment of their own troops not insignificant. It was therefore recommended to the weapon masters to rivet a leaf spring inside the winter trigger, which forced it away from the grip when released. Production numbers are unknown, but they were probably very low. In November 1944, the magazine “Of the front for the Front” showed guidance for building a completely simple winter trigger; consisting only of a small piece of wood and a little wire.

Other weapons were not better off. Even for the standard rifle of the German soldier, the carbine 98k, a winter-trigger wasn’t introduced until 10 October, 1944. It was a simple sheet metal product, which was put laterally into the trigger guard and secured with a counter plate. Small differences of the trigger guard dimensions rendered a use to the MP 40 submachine gun and the MP 44 assault rifle impossible. For these two weapons a slightly deviating variant had to be manufactured. In order to avoid mistakes with the similar looking devices, they were marked with respectively with “Mod 98”or “MP.”

If the soldier now had a winter trigger on his MG, he still had to ensure that his weapon was always operational even with the snow and great cold. A cover of canvas (called “Systemschützer” / system-protector), which was industrially manufactured both for the MG 34 and for the MG 42, provided a certain protection against penetrating snow. It was wound around the receiver and fastened with leather straps. In addition there was a muzzle cap from plastic, which could be shot through in case of emergency. While there was an officially introduced canvas cover for the K.98k likewise, the owner of MP 40 had to make their covers themselves following guidance in “Of the front for the Front.”

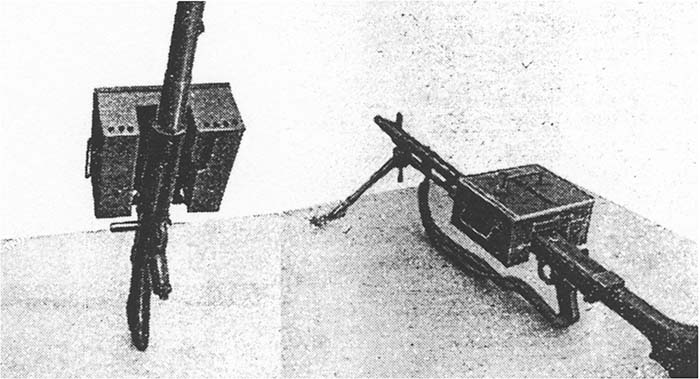

A remedy for problems caused by the great cold was more difficult. Despite advancement of the lubrication oils, weapons often froze at temperatures of -30 to -40 °C (-22 to -40 °F) and were not operational at the crucial moment. Adding gasoline or kerosene did not always help and often the soldiers had to urinate on their weapon in order to loosen the frozen parts and to prevent breakage of now brittle system parts. This problem brought an ingenious weapon technical sergeant named Karl-Heinz Raschke on the scene: He designed a preheater for the MG 34 and the invention was published in the magazine “Of the front for the Front” in May 1944. The preheater was a sheet metal box to put on the MG housing from above. Heat was generated by a small quantity of charcoal. Holes in the preheater let warm air waft to the MG housing, which was warmed up in this way. The heat was barely sufficient in order to ensure a perfect function on the one hand and to avoid an annealing of the system’s springs on the other hand. An advantage was that the MG could remain completely oiled in the emplacement. With suddenly approaching enemy the preheater could be removed quickly and only the ammunition belt had to be inserted into the weapon. When not in use, the preheater could provide good services as a shelter stove.

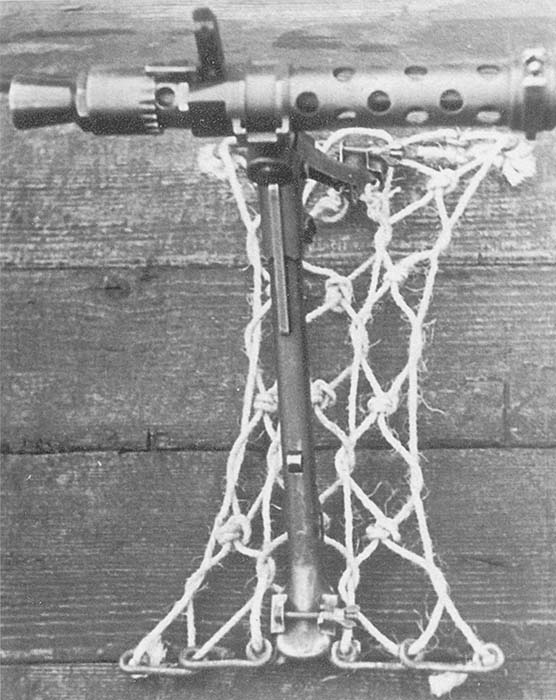

A further problem in winter fighting with machine guns is the sinking of the bipod in the snow. No precautions had been met before the Russian campaign. Not until October 1944, the winter combat training and experimental group of the troops made first attempts for solving the problem with bipods in the snow. A number of different constructions were tested extensively and nearly three months later, on 15 January, 1945, a solution was found: Width of materials (tents, burlap bags, etc.) proved better than an under-layer made of netting, because the latter sunk into the snow when the weapon vibrated during shooting. It was suggested to communicate this solution to the weapon masters in the field. But those had already gained their own experiences after so many years of war. Already in June 1944, a building guidance for a carrying frame that could also be used as a simple gun carriage was published in “Of the front for the Front.” The Norwegian army backpack formed the basis, which was supplemented by an MG mounting plate and two foldout snow plates. Finds in Norway and Finland prove that this construction was actually copied and used. In some cases even with some modifications of mountings for reserve belt drums.

Still in February 1945, the infantry school at Döberitz got an invention proposal for sledge skids for the heavy MG tripod. Despite the simple building method, the trials resulted in a full field serviceability without impairment of the stability. And both in the snow, and on sand or grass ground, the skids eased getting in position substantially, because the soldier could push the tripod from behind. So far by the weight of the weapon and the spikes under the tripod-legs the necessary jerky “forward-throwing” of the tripod could be avoided in such a way.

Once again it proves to be true that emergency makes for inventive action.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V16N4 (December 2012) |