As the warm Spring of 1910 melted away the cold winter in the Mid-Atlantic states, the Pittsburgh Pirates were preparing to defend their position as the World Champions of professional baseball, President William Howard Taft was vigorously continuing the legislative reforms begun by his predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt, while from Mexico, a Hearst journalist named J. F. Albert was sending back reports of revolution from that wild land: “Díaz government officials are denying reports of a popular uprising being led by a rebel named Zapata in support of Francisco Madero, the reform candidate for the presidency. The revolt is said to be in the state of Morelos, to the south of Mexico City.”

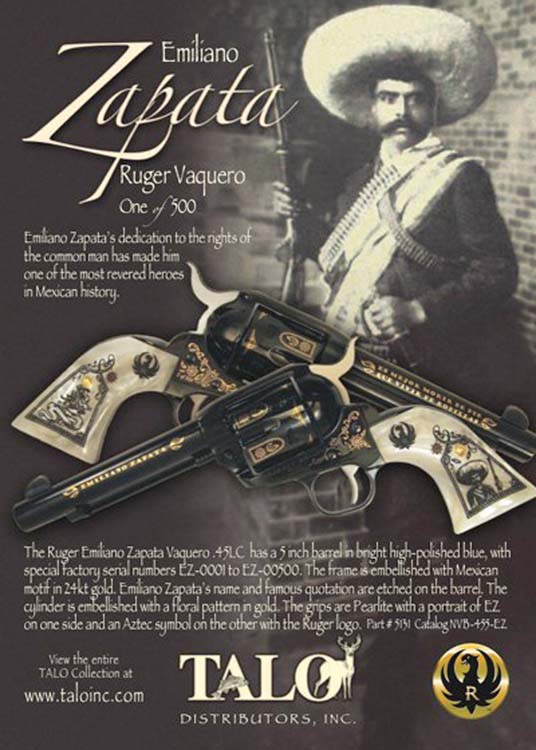

Zapata never formally ruled Mexico and his army never outnumbered that of his ally, the bandit Pancho Villa. Unlike other greedy and ambitious revolutionaries, Zapata had a single goal: land reform for the common citizen.

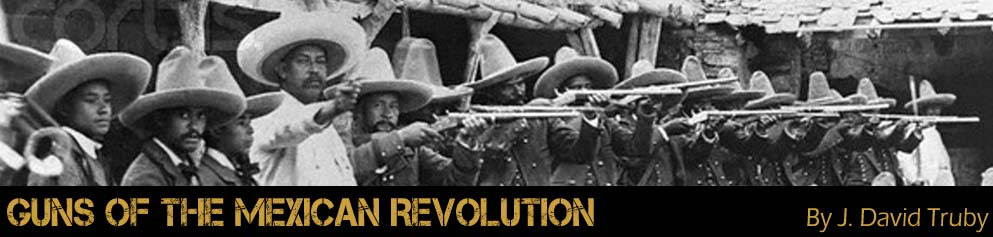

While Mexico’s national forces and police had arsenals of modern firearms and open channels of mass supply, revolutionaries did not. Their arms suppliers, financing and methods were as blurry as the borders they illegally crossed to supply the freedom fighters.

For example, late in 1910, an innocent looking wagon entered Zapata’s small village in Southern Mexico, loaded with hay. Beneath the hay rested 60 Winchester Model 1886 and 1894 rifles, 30 Colt revolvers, and 2,800 rounds of ammunition. The Zapata peasants had their start-up arsenal of vintage American frontier weapons to fight the federal troops armed mostly with new model Mauser bolt action rifles.

History placed Emiliano Zapata into the eye of this revolutionary storm, curling its deadly cyclones around the corrupt establishment. Indeed, today there are more statues of, and other tributes to, Emiliano Zapata throughout Mexico than of any other revolutionary figure.

President Diaz’s top general, Victoriano Huerta and his troops chased the small band of loyal Zapatistas across the mountains of Morelos. Yet, the rebel army grew in size through autumn of 1911, fed by the people’s hatred for the murderous Huerta. One Mexican leader said of Zapata, “Emiliano Zapata is no longer just a man; he is a symbol for other men.”

With success, more arms and material came his way. As the Hearst journalist William Jenkins wrote: “Instead of the battered, old handed down guns and captured rifles, crates of new Winchesters and even some Mausers were showing up in Morelos. We are told they have been bought by friends to help Zapata’s armies in their battle in the South. Clearly, they come from the North. How far north is anyone’s guess to make…. Ammunition, too, as I saw crates of it. Before, these soldiers had to beg for even a few cartridges. Some loaded their own powder and ball. Today, they have modern factory ammunition and a good supply of it… it keeps coming here in the same type of plain wagons… sometimes by train.”

“Matters will change when we get some artillery and some more of these modern Mauser rifles,” Zapata informed one of his agents who was dealing with Texas gunrunners. “We need Mausers and the automatic machine guns… Can we obtain the American Springfield and ammunition for all the guns?”

Zapata didn’t place firearms in the planned obsolescence category that industrialized military societies do to market new technology even before their old creations are worn out. As long as a gun fired, Zapatistas used it. Firearms authority E. Dixon Larson writes, “There is no question that those (old firearms) that have seen service in Mexico will easily outrank all others in a use and abuse exhibit of grueling wear and unorthodox modification.”

According to most historical accounts, the majority of weapons used came from the United States, with Europe a distant second. Colt and Winchester models outpaced all of the others by 30 to 1. But, getting modern military guns in the United States proved impossible as the American government gave military equipment to the “rightful and orderly” Mexican government, but denied weapons to “any rebel group.”

Obviously, blockades, like prohibitions of any sort, are made to be broken. Lives and fortunes were both won and lost on the Texas and Arizona border with Mexico and along both the Gulf and Pacific coasts, as dozens of gunrunners sought to sell modern weapons. The U.S. and Mexican governments attempted to stop weapons coming in for rebel forces. But, when smugglers are into serious profit, a few dollars or a few pesos change hands, heads are turned and the goods go through.

According to contemporary reports, observers saw some machine guns with the Zapata forces, usually old Colt potato diggers, a few Gatling guns, but at least ten newer Maxim guns. By 1916, Zapata had a dozen or so Lewis guns, some stolen from U.S. units, others “donated” by friends of the Revolution.

Naturally, a helter-skelter ordnance system created logistical supply headaches, e.g. matching ammunition caliber with differing rifle calibers, obtaining a machine gun without vital parts, etc. In addition to the smuggled weapons, Zapata’s forces had homemade guns, plus weapons stolen from the established military and police. Sometimes, new weapons would come in with the wrong caliber ammunition, or no ammunition would show up for any weapon. Many of the peasants brought their own rifles from home, for which no modern ammunition existed.

The basic rifle of the federal soldier during the Zapata period was the Mexican Mauser Model of 1902 in 7mm; an excellent, hard-hitting, accurate rifle. Zapata told a reporter from Literary Digest, “The old Winchester saddle rifles our boys have are no distance match against the army’s new Mausers.”

The Mexican government also purchased numbers of the Mauser Model 1912, a rifle very much like the German Model 98 rifles. The only major difference is that the Mexican model has a tangent-type rear sight and a longer hand guard than the German rifle.

The Mexican military also bought quantities of the 7mm Arisaka rifle from Japan. This five-shot weapon is very much like the standard Japanese model of 1899, and was used through the 1920s.

A very unusual weapon that found some common favor among the rurales of Porfirio Diáz was the Pieper-Nagant, a nine-shot, 8mm rifle with a revolving cylinder. Made in Belgium, the weapon’s barrel is completely enclosed in the wooden fore end. The cylinder closes with the barrel to make a gas-tight, leak-proof seal.

The Mondragón rifle, known officially in Mexico as the Fusil Porfirio Diáz Systema Mondragón, Modelo 1908, was conceived by General Manuel Mondragón in the late 1890s, but he did not perfect and patent his design until 1907. He was forced to have his semiautomatic rifle manufactured by SIG in Switzerland, as there were no suitable production facilities in Mexico. Although the Mondragón is best known for its use by several European countries, the Mexican Federal Army imported a number of them in 7mm, adopting the weapon in 1911. The Mexican models were fitted with a box magazine into which an 8-round clip was loaded. In addition, a few of these pioneer auto-loading rifles were produced in 5mm.

In those days, Mexico was often called a machine gun seller’s paradise, and the Revolutionary era government used a variety of the automatic weapons, mostly the 1896 Hotchkiss gun in 7mm, later, the 7mm Browning model 1919, the 7mm Colt Automatic Gun “Potato Digger” of 1895, plus the Model 1911 Madsen machine gun.

Anyone who has examined the thousands of pages of text, reports, interviews, as well as several thousand period photos, can safely conclude that just about every type of period firearm from homemade hand cannon to machine gun was used in the Mexican revolutionary decade.

“If it shoots, it’s welcome in the Revolution,” Emiliano Zapata told an old man who offered a crude, homemade shotgun to the Chief in 1913. As reported by Literary Digest in 1912, “Zapata creates a faithful follower by handing him a rifle and shells. And to the average Mexican, a rifle means everything.”

A Zapata aide, General de la O, recalled, “We were always happy to see deserters from the federal troops bring along their Mauser rifles. Emiliano wanted very much for his boys to have the best. We were a very raggedly armed bunch, some men had muzzle loaders nearly 100 years old. There are never enough brave men who risk death to bring us modern weapons.”

In August of 1914, knowing that a majority of his men were armed with antiquated Winchesters that had already seen rough service on the North American frontier, handed down family antiques and 40 year old French rifles, Zapata decided he would have to raid more federal arsenals and trains. It worked.

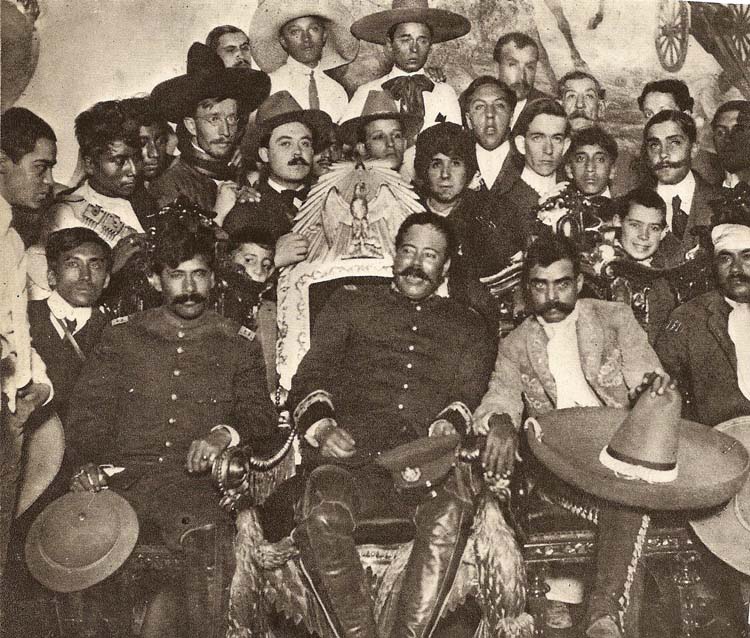

Zapata’s men came into Mexico City on November 24, 1914, acting more like peasants lost in a big city than conquering soldiers. Pancho Villa’s Villistas joined the Zapatistas in the capital on November 28. The historic personal meeting between Villa and Zapata took place December 4, 1914, in Xochimilco, a small town outside of the city. Villa offered Zapata modern arms and ammunition, while Zapata offered men and silver. On December 6, 1914, the two chiefs led their armies into the capital in a peaceful joint occupation.

The peace soon ended in the South. By July 30, 1915, the army of General Pablo González was pushing through Mexico City toward Cuernavaca. Aroused, the Zapatistas took to war again. Zapata celebrated his 36th birthday by driving González and his soldiers back to Mexico City, telling him to stay out of Morelos; then he tried to retire to peace once more.

“Instead of fighting all the time, why can’t we simple people be left alone in peace to enjoy what we fought for?” he asked his friend and advisor Antonio Diáz Soto y Gama. He probably never learned the answer to that question, even though the next three years were somewhat less warlike.

Money and politics had largely replaced bullets as the major weapon. Indeed, in the spring of 1919, the increasingly repressive government, now headed by President Venustiano Carranza, invited Zapata to a luncheon to discus land reform.

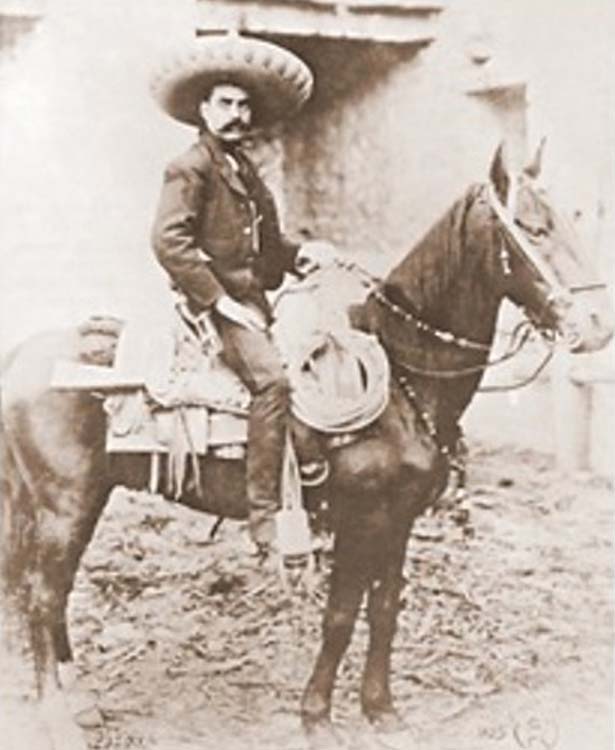

As April 10, 1919 dawned, Zapata and nearly 150 of his men rode into a hacienda, about 35 miles south of Villa de Ayala, without suspicion. Shortly after 2 p.m., he rode his horse back inside the hacienda walls for a luncheon of beer and tacos, as a guest of Col. Jesus Gujardo, an aide to Pres Carranza, who had made the invitation to this peaceful sit-down for both sides. Privately, Guajardo had hinted he was ready to defect to Zapata’s side of the political revolution, which was what drew Zapata out of his home district that day.

Guajardo had a small honor guard lined up inside, supposedly to receive Zapata. Three times the bugle sounded the honor call, then as the last note died, the honor guard, made up entirely of government officers dressed as enlisted men, suddenly raised their Mausers and fired point-blank at Zapata and the handful of men who rode behind their chief. Two volleys were fired. Zapata was killed instantly, assassinated at age 39 by a turncoat. A young Zapata aide who survived, Reyes Avilés, wrote of the murder: The surprise was terrible.

The soldiers of the traitor Guajardo were firing on us… resistance was useless. On one side, we were a fistful of men thrown into consternation by the loss of our loved Chief; and on the other side a thousand of the enemy… This is how the tragedy was.

On orders, Guajardo’s troops grabbed the dead rebel leader as his body fell from the horse. A dead Zapata would be powerful propaganda, so immediately, the body was taken to Gen. González’s headquarters and placed on public display in the city of Cuautla. His supporters all over Mexico brought back his famous quote, “We die again. But, this time, to truly live.”

One old veteran of the Revolution said, “Emiliano now rides with the wind. But he is here and he will always ride with us. You can see him too if you look on the right hill at the right time. Zapata is forever.”

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V14N11 (August 2011) |