By Charles Q. Cutshaw

Heckler & Koch has gained a well-deserved reputation as an innovative small arms manufacturer that is highly responsive to the requirements of the users of its products. H&K also is very sensitive to trends in the small arms market and is often ahead of its competitors in introducing state of the art small arms for military and police use. In the present case, H&K has introduced two new small arms, one completely new and another an innovative derivative of an existing product.

H&K PDW

Personal defense weapons (PDWs) are a current small arms “hot button.” The United States led the way with a PDW requirement some five years ago, but never brought the requirement to a solicitation and the American PDW requirement is essentially dormant. Britain’s Ministry of Defence, however, issued a solicitation for a PDW in late January of this year, with the declared intent to purchase some 15,000 examples of the weapons between 2003 and 2005. H&K’s development of their latest product line was clearly in anticipation of the current UK requirement and others to follow. PDWs are intended to arm soldiers whose duties are not near the forward combat area, soldiers whose duties require their hands to be free, and soldiers whose duties do not normally require an infantry rifle. They essentially bridge the gap between pistols and rifles, being chambered for a cartridge whose ballistics exceed those of the former, but are less than those of the latter. In that context, H&K’s new PDW is the quintessence of a PDW.

Whether or not PDWs as a class of small arm will establish itself is not within the purview of this brief article, but we believe that any new weapon such as the PDW entails a degree of risk. IDR recently had the opportunity to fire H&K’s PDW and examine it in detail.

From a technical standpoint, H&K’s PDW is a state of the art weapon. The receiver and external components are virtually all of polymer construction, in keeping with other recent H&K designs, such as the G36 rifle and UMP submachine gun. The PDW is chambered for a new cartridge, the 4.6x30mm, developed as a joint venture between H&K and Royal Ordnance Radway Green. We will discuss the new cartridge in some detail below. H&K’s PDW is a locked breech, select fire, gas operated small arm. The gas system utilizes a short-stroke piston to drive the bolt carrier assembly to the rear. The PDW has a cold hammer forged chrome plated barrel with six lands and grooves of a right hand twist. The bolt mechanism uses the tried and true Stoner principle with a multiple lugged bolt in a bolt carrier that uses a cam and pin mechanism to lock and unlock the breech. The reflex sighting system is made for H&K by Hensoldt and is mounted on a MIL-STD-1913 rail. The optical sight has relatively long eye-relief so it can be used either close to the eye when the PDW is fired as a carbine or at arm’s length when the PDW is fired as a pistol. The optical sight works either by using ambient light or under low light conditions from a battery or tritium insert. There are backup open sights in case the optical sight becomes damaged or is removed. The PDW feeds from a detachable staggered row box magazine. Two magazine capacities are available – 20 and 40 rounds. The magazine well is in the weapon’s pistol grip. The PDW has a folding foregrip and collapsible buttstock. Cyclic rate is approximately 700 rounds per minute.

We found the H&K PDW to be very pleasant to shoot, despite the fact that the pistol grip is nearly vertical, which we thought would make the weapon awkward to handle, but this was not the case. The controls are well-placed, fully ambidextrous and intuitive to use. The sliding buttstock retracts easily into its fully extended position and the foregrip aids in maintaining control in fully automatic fire. Our only possible complaint about this little weapon is the fact that its barrel is so short that the potential exists for a user to place his or her hand over the muzzle under stress. We should note, however, that H&K has placed a “hook” at the forearm tip to prevent one’s hand from overriding it and inadvertently covering the muzzle with the hand. New prototypes will have threaded barrels to extend the muzzle by adding quick detachable flash suppressors, compensators, blank firing adaptors, or sound suppressors. That said, we preferred to shoot the little PDW using the folding foregrip. The PDW was easy to control both in rapid-fire semiautomatic and full automatic. Felt recoil was negligible and muzzle rise virtually nonexistent. We fired the weapon at ranges of 25 and 50 meters, the latter distance representing about the limit of the realistic effective range of such a weapon and found that we were able to place a high percentage of bullets in the center of mass of our silhouette target. The reader will note from our discussion of the 4.6x30mm cartridge below that the PDW can be used effectively to a range of at least 100 meters. Shooting H&K’s PDW can best be described as pleasant and uneventful, which is a tribute to the overall excellent design of the little weapon and its diminutive 4.6x30mm cartridge.

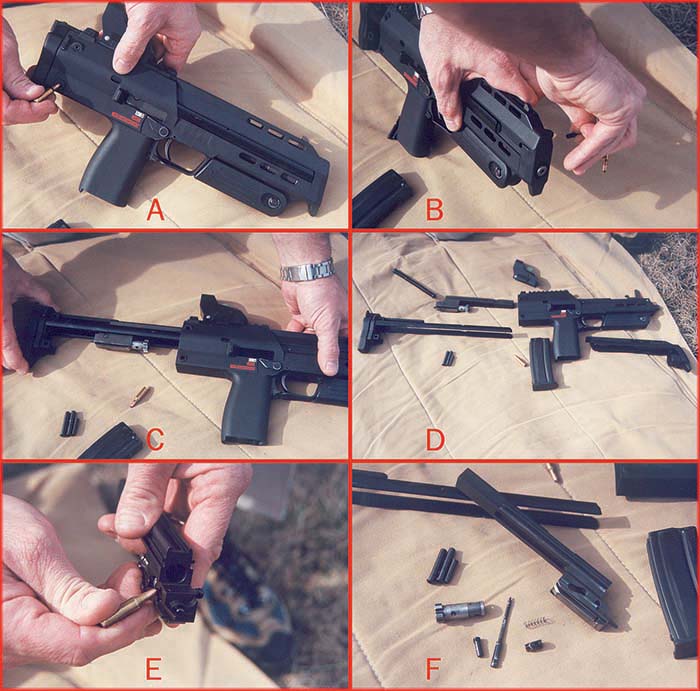

Field stripping the little PDW for cleaning and maintenance is simple and can be accomplished without tools, unless one counts a cartridge as a “tool.” The cartridge is used to press out pins that retain the upper and lower receiver sections and the buttstock assembly, which retains the recoil mechanism and bolt carrier assembly. The cartridge is also used to disassemble the bolt carrier assembly when required. The photo of the stripped PDW shows the simplicity of the little weapon.

A key element of H&K’s PDW design is the 4.6x30mm nontoxic cartridge, which has not been standardized by any NATO country as of the time of this writing. The cartridge fires a solid steel copper plated 24.7gr bullet at a muzzle velocity of 2379 fps, resulting in a muzzle energy of 312 ft-lb. For comparison, the standard British military 9x19mm cartridge has a muzzle velocity of 1299fps and a muzzle energy of 430 ft-lb. These simple numbers, however, are somewhat misleading and do not fully explain why a smaller, lighter projectile may prove superior to a larger, heavier one. The 4.6mm bullet has a high ballistic coefficient and is fired at a higher velocity than the 9mm, which gives it a flatter trajectory and greater range. The 9mm bullet, for example, will not defeat the standard NATO CRISAT target (1.6mm of titanium and 20 layers of Kevlar(r) at 50 meters. The 4.6mm bullet, on the other hand, will defeat it at over 100 meters, with sufficient velocity to transfer 85 ft-lb. of energy into and completely perforate a 150mm thick block of ordnance gelatine behind the armor barrier. This greater terminal performance also has to do with the fact that the 4.6mm bullet is copper plated solid steel while the 9mm bullet is copper with a lead core. We should note that H&K states that the PDW’s 4.6mm bullet will also penetrate NATO’s CRISAT armoured personnel target at 200 meters. Although we cannot dispute the claim, the ability of so light a bullet to inflict an incapacitating wound after having passed through 1.6mm of titanium and 20 layers of Kevlar(r) at 200 meters range is questionable. H&K and Radway Green are also developing tracer, frangible, JHP, training (Solid copper bullet), blank and plastic training ammunition for the PDW.

In sum, H&K’s new PDW is an excellent overall design. It is handy, lightweight and can be fired either as a carbine or a pistol. Despite the fact that the 4.6x30mm cartridge offers improved penetration in comparison to standard NATO 9mm pistol ammunition, some may object to the cartridge on the basis that adopting H&K’s PDW will force adoption of an additional small arms caliber into an already complex ammunition logistics system. Only time and the acceptance of PDWs as a class of weapons will tell whether H&K’s latest product will be a success.

G36C

H&K’s recently announced miniature assault rifle, the G36C (Commando) is based on the G36 assault rifle which IDR test-fired in late 1998, so we will not go into any great detail on the description and functioning of the rifle, as the principal features of the parent rifle are well-known. The basic G36 is a gas-operated select fire assault rifle for general issue to infantry soldiers. It is noted for its reliability under adverse conditions and its simplicity of operation. The G36C is intended primarily for special operations units that require an extremely compact carbine for close range engagement (CRE) ranges to 50 meters. (The G36C is truly a carbine in the classic sense because it is a short barreled version of a full-sized rifle.) Whatever it is termed, the G36C carries all of the best features of the G36 into an extremely compact package. Simply stated, we liked the original G36 and we like the G36C. It is comparable in size to a 9x19mm MP5A3 submachine gun (See accompanying photo.), yet fires a 5.56x45mm cartridge which totally outclasses any pistol caliber round (9x19mm, 10mm or .40 S&W) fired by the MP5. It is compact carbines like the G36C that are spelling the demise of the submachine gun in many military special operations units. Pistol-caliber submachine guns simply do not have the effective range, terminal ballistics, or versatility of compact carbines and so are beginning to be phased out of many major military special operations forces. The G36C is one of the best compact carbines we have encountered. It is lightweight, versatile, and easy to operate and like most H&K firearms that we have encountered, pleasant to shoot. If its parent G36 is any indication, the G36C will also prove to be extremely reliable.

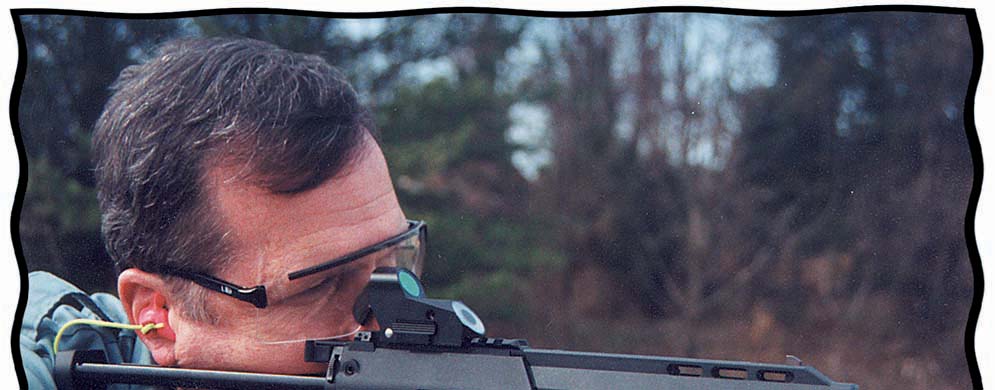

The G36C incorporates MIL-STD-1913 rails on the upper carrying handle and lower forearm to mount optics and other accessories. The example we test fired was equipped with a Knight’s Armament foregrip that clamps to the adapter rail. This foregrip makes the weapon easier to control on full-automatic fire. The G36C is also equipped with an advanced design Vortex-type flash suppressor that virtually eliminates muzzle flash, which is always a problem with short-barreled carbines due to incomplete combustion of powder in the shortened barrel. Although the G36 has a short sight radius, we did not find that to be a problem in our shooting. Whether we fired semi- or full automatic, the little G36C was easy to control and keep on target. There was slight muzzle rise, but it was easily controllable.

Although it is commonly accepted that velocity loss in compact carbines such as the G36C reduces the muzzle velocity to approximately 1800 fps, we wish to emphasize that this is most definitely not the case either with the G36C or with any other compact carbine. Standard SS109 (M855) ammunition has a muzzle velocity of 3051 fps when fired from a 20 inch barrel. The same cartridge fired from the 8.9 inch barrel of the G36C has a muzzle velocity of 2369 fps – a loss of some 656 fps velocity. At close range engagement (CRE) ranges at which carbines such as these are intended to be used, there is more than sufficient velocity and energy to maintain desired levels of lethality.

In the final analysis, we found the G36C is a very satisfactory weapon, based on our brief experience with it. The reliability and ruggedness of the parent G36 rifle is well established. If this new addition to the G36 family approaches its parent rifle in these areas, it will appeal to any organization seeking a compact carbine for close range engagements. The G36C will enter full production and will be available in September 2000.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V4N1 (October 2000) |