By Al Paulson and N.R. Parker

The growing involvement of U.S. armed forces in Vietnam stimulated the deployment of the new rifle developed by the late Gene Stoner and his colleagues at ArmaLite as the AR-15, and produced under license at Colt as the M16 once adopted by the U.S. military. SpecOps personnel soon recognized the value of suppressed weapons in general, and suppressors for the little black rifle in particular. The U.S. Army’s Human Engineering Laboratory (HEL) at Aberdeen Proving Ground developed a number of suppressors for the M16 rifle from the early 1960s onward.

Al Paulson photo.

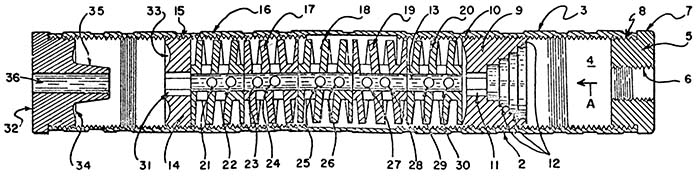

The HEL M2 was an experimental M16 suppressor that used a series of baffles coupled with an expansion chamber extending back over the barrel to the front sight. The M2 model for the M16 rifle was 14 inches long and used 24 baffles forward of the muzzle. Following an ENSURE (Expediting Non-Standard Urgent Requirement for Equipment) request (DA ENSURE Index No. 77) from the USARV (United States Army, Vietnam) for silencers for the M16A1 rifle in May 1966, HEL designed and tested a noise suppressor designated the HEL M4, which was a variant of the M2.

To reduce the bulk and weight of the M2 5.56mm suppressor, HEL shortened the length to 12 inches, reduced the number of baffles, and changed the internal arrangement of components. The number of baffles was reduced from 24 to 11, with the first baffle being positioned backwards (i.e., so that its apex was toward the front of the suppressor). Directly in front of this baffle was a short expansion chamber followed by a baffle positioned normally (i.e., with its apex toward the muzzle of the rifle). This baffle had a very large bullet passage, presumably to reduce back pressure. The next 9 baffles were the same design as the first baffle, but were oriented normally.

The new can eliminated enough of the muzzle blast so that the location of the shooter was undetectable to hostiles downrange, which greatly improved a shooter’s tactical advantage and survivability. Given ideal vegetation and terrain, the muzzle blast from an M16A1 was completely indistinguishable beyond 50 yards. Only the sonic boom created by the 5.56mm projectile remained, which sounds something like the report of a short-barreled .22 rifle. In the absence of a muzzle blast, the mammalian brain interprets the origin of the gunshot as perpendicular to the pressure wave of the ballistic crack striking the body. Combined with the sound of bullet impact, this phenomenon causes individuals to turn their attention 90 to 180 degrees away from the shooter. This is a very good thing during an ambush or when a small force equipped with silencers must cope with a larger force.

To meet the ENSURE #77 requirement, the USARV submitted an acquisition requirement for 1,080 HEL M4 noise suppressors. By December 1967, the first 120 suppressors had been produced, but further production was suspended pending a field evaluation by USARV. Twenty suppressors were sent to USARV for testing.

In March and April 1968, the USAIB (United States Army Infantry Board) tested the M4. The USAIB test found that the M4 had three shortcomings. (1) The gas deflector failed to deflect all of the escaping gases from the firer’s eyes. (2) The ejection pattern of the rifle with noise suppressor attached caused the spent cartridge case to strike the cheek of left-handed shooters. And (3) the malfunction rate of the test rifle was significantly higher than the control rifle during automatic fire. The USAB concluded that the HEL M4 sound suppressor had military potential but it was not the perfect tool for the job, so the Board returned the M4 to HEL for correction of these shortcomings.

Early development at Aberdeen also demonstrated that the M4 generated a number of problems with the M16A1 rifle: (1) increased back pressure; (2) increased cyclic rate; (3) increased rearward bolt velocity, and (4) excessive gas discharge from the ejection port into the shooter’s face. The major problem was the increased back pressure, which actually produced the other problems, such as shearing off the bolt carrier key. HEL solved the bolt velocity and cyclic rate problems by adding an additional gas pressure relief port to the bolt carrier, which enabled reliable functioning of the rifle whether the selector was set to SEMI or AUTO.

The only glitch with this solution was that the rifle would not cycle reliably with the modified bolt carrier unless the suppressor was installed. This meant that a rifle fitted with the modified bolt carrier had to be dedicated for suppressed use only.

Once installed, the suppressor became an integral part of the rifle that could not be removed without swapping the bolt carrier as well. This was not an ideal situation for special operators. Furthermore, the suppressed rifle with modified bolt carrier still dumped a lot of hot combustion gas into the shooter’s face, so HEL added a special gas deflector to the charging handle of the M16A1 rifle. This deflector was not entirely successful, however. In April and May 1968, HEL developed a new, shorter suppressor that eliminated the need for a specially modified bolt carrier. Apart from the removal of 5 baffles from the baffle stack, the new suppressor used the same arrangement forward of the muzzle of the rifle. This new 9.5 inch model was known variously as the HEL M4A, or H4A, or E4A which was its final designation. The gas deflector was also intended to be used with the new suppressor, but there is little evidence to suggest that it was actually used with the E4A suppressors in the field.

Other developers of noise suppressors tried to meet the ENSURE #77 requirement, including SIONICS (a commercial company that eventually merged with the Military Armament Corporation) and Frankford Arsenal (FA; which was a government facility). In May 1968, HEL, SIONICS and FA submitted a total of seven different noise suppressors for testing to meet the ENSURE #77 requirement. The Frankford Arsenal silencers were 1.25 inches in diameter and utilized porous aluminum rather than baffle technology. These very early SIONICS silencers used WerBell’s spiral diffusers, but did not incorporate baffles that would later be seen in his patents and production units. They also featured a flash hider that screwed onto the front end cap of the SIONICS silencer. The HEL M4 and M4A suppressors were tested at Ft. Benning, Georgia, by the USAIB in a Military Potential Test (MPT) against the FA (Frankford Arsenal) FA XM and CM noise suppressors and three different versions of the SIONICS 5.56mm suppressor (the MAW-A1, A2, and A3 models). The test recommendation was that the HEL E4A noise suppressor was suitable for a field evaluation in Vietnam.

The HEL E4A was win-win technology. While it was not as quiet as the M4, it solved all of the reliability and durability issues plaguing the M4 suppressor. Furthermore, it was more compact than the HEL M4. While the E4A did not require a modified bolt carrier (unlike its M4 predecessor), we find it quite interesting that the E4A was considered to be a permanent fixture once it was fitted to a rifle.

The E4A produced a net sound reduction of 26 dB (at 12.5 feet down range and 2 feet to the right of bullet trajectory). That was significantly better than the SIONICS suppressors (by about 10-11 dB), but not as good as the HEL M4 (which produced 35-36 dB reduction) or the FA XM (which produced 32-36 dB reduction). See the accompanying sidebar to learn more about the sound level measurement procedures used for these HEL tests. All of the other five suppressors tested by the USAIB had shortcomings. The performance of the E4A out-shone the other suppressors, especially with regard to the number of malfunctions that occurred during cyclic tests. The malfunction rate of the E4A was significantly lower than all other suppressors tested; during a 1,000-round cyclic rate test, only 3 malfunctions occurred with the E4A.

While some shortcomings were noted with the SIONICS suppressors, SIONICS was well advanced in the use of high-tech materials compared to the other suppressor manufacturers of the time. SIONICS used a plastic bushing under the rear retaining collar. Unfortunately, this bushing melted during a full-auto testing. A redesigned bushing made from Teflon was then submitted during the MPT to rectify this problem. Unfortunately, Teflon melted when temperatures reached about 1,000 degrees F, so SIONICS finally settled upon making the bushings from naval bronze.

Another problem was the gas pressure relief valve. The springs used in the relief valve failed during the cyclic rate testing, so a redesigned spring made from Inconel was submitted in an attempt to rectify this problem. Even resorting to using a high-temperature resistant alloy like Inconel proved unsuccessful, so SIONICS developed its third and final design: a passive gas pressure relief valve with no moving parts. Significantly, the MPT found that the pressure relief valve had no effect on the operation of the test items, and concluded that it was an unnecessary part of the suppressor. It is also interesting to note that use of a gas pressure relief valve with center-fire rifle suppressors has not been seen since its use in the SIONICS suppressors, with one exception. Recently deployed Israeli-made centerfire rifle suppressors for the M16A1 and M14 rifles have featured the use of gas pressure relief valves, despite the fact that advances in internal design have clearly eliminated any need for pressure relief valves.

Two of the SIONICS suppressors used titanium spiral suppressor rings, while the third used aluminum spiral suppressor rings. Following further destruct tests at Ft. Benning, SIONICS made significant changes to the construction and materials used in the 5.56mm suppressors. No internal parts were subsequently made from aluminum, and stainless steel became the material of choice. While the use of titanium has become more widespread in recent years, it is a little-known fact that SIONICS pioneered the usage of titanium in firearms sound suppressors, though undoubtedly the cost factor prevented its widespread use during the Vietnam years. Despite the advances in material use, the SIONICS/MilitaryArmament Corporation’s suppressors were not as widely used as the HEL E4A in Vietnam.

After the MPT report was published in September 1968, final production of the outstanding 960 HEL E4A suppressors was completed, and these were shipped to Vietnam in late 1968 and early 1969 at a cost of $42,000. That works out to less than $46 per unit. According to several sources, the HEL E4A suppressor was used in greater numbers during the Vietnam War than SIONICS/Military Armament Corporation’s suppressors designed for the M16A1 and CAR-15. Rangers, SEALs and Army Special Forces began using HEL M4 silencers in the summer of 1968 and then upgraded to the HEL E4A suppressors, which were employed throughout the remainder of the Vietnam War. The SEALs, however, eventually used a U.S. Navy-developed 5.56mm suppressor rather than the E4A suppressor.

Surprisingly, both the HEL M4 and E4A suppressors were considered to be expendable items. If they were damaged, they were to be destroyed by the company armorer rather than repaired. This may explain why the HEL M4 and E4A suppressors are rarely seen today in collectors’ hands. It is known that during the early 1980s, at least one mail-order company was selling parts kits for the M4, although this practice ceased when ATF changed the definition of a silencer to include silencer parts. If you ever find a transferable M4 silencer, it’s a rare and important historical artifact from the Vietnam War.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V5N8 (May 2002) |