Hiram Percy Maxim firing a.30 caliber French Benet Mercie machine gun fitted with a Maxim silencer.

By Frank Iannamico

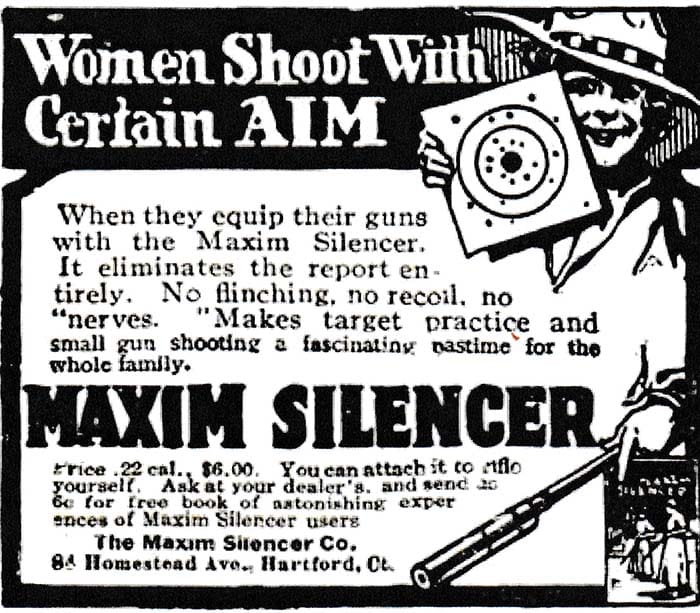

Although sound suppressors, also known as silencers, have recently hit an all-time high in popularity, they have been available for over 100 years. Suppressors have slowly begun to shed the stigma of being a tool for criminal use, largely a myth unjustly perpetuated by Hollywood.

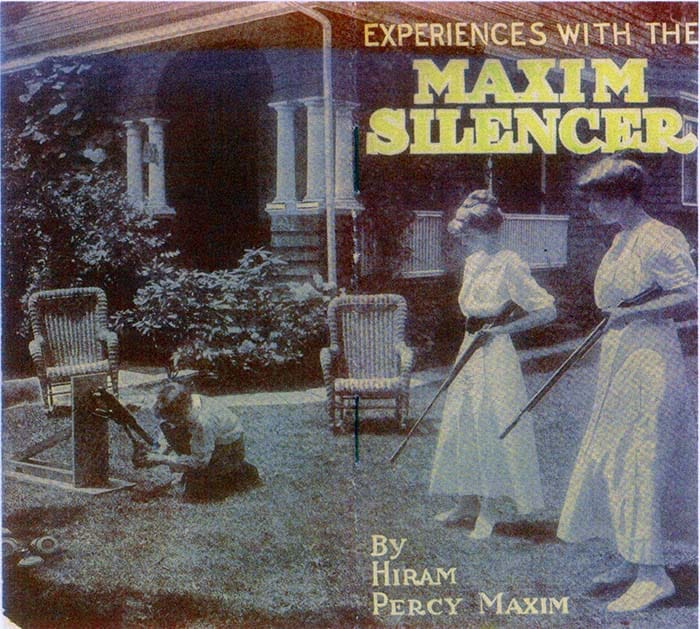

During the early 1900s a significant number of people in America lived in or close to cities. Firearms were common place, and the police were usually not alerted if someone was seen walking down the street with one. Although the carry of a firearm was accepted, the noise of firing one in populated areas was considered somewhat annoying to many residents.

Hiram Percy Maxim, son of the famous Maxim machine gun inventor Hiram Stevens Maxim, theorized that the report from a firearm could be reduced by slowing down the gases leaving the muzzle of a firearm. Suppressing the report of a gunshot would have many advantages: it would not disturb the neighbors, and would allow the shooter to practice without the noise, hearing discomfort and subsequent hearing loss. During the 1900s hearing protection, if used at all, consisted of placing wads of cotton in one’s ears.

One of Maxim’s first concepts was to use a design that would swirl and momentarily trap the high pressure gases in a transversely mounted chamber and slowly vent them through a series of spring-actuated valves and ports. The design was complex and its performance in reducing a firearm’s report marginal. The idea for using a series of valves and springs to slow the escaping gases, and reduce the report of a firearm, was a common concept during Maxim’s day. There were a number of U.S. and foreign patents issued for firearm silencers prior to Maxim’s but most were based on theory, there were few known working models.

Undeterred by the marginal performance of his first silencer, Maxim embarked on an entirely new idea using a series of baffles to slow the escape of the gases. The baffle system proved to be simpler in design and far more effective. After a number of experimental “silencer” designs in different configurations, Maxim produced his first sound suppressor offered for sale to the general public.

The Maxim Silencer Company

Hiram Percy Maxim’s first successful commercial suppressor was the .22 caliber Model 1909. The unit was made of relatively soft steel, having an overall length of 4.88 inches, with an outside diameter of 1.35 inches, and a weight of 6.8 ounces. The most common right-hand threads used for attaching the Maxim .22 caliber suppressors to their host firearms were 1/2-inch diameter, 20 threads per inch. The Maxim 1909 used stamped steel baffles to slow down the escaping gases. Maxim’s silencer was sealed and not designed to be disassembled, the outside surface of tubes had a bright blue finish applied. The suppressor tube was a concentric shape that obstructed the shooter’s view of the front sights on most firearms of the day. The top surface of the endcap was stamped “22 CALIBRE” the face of the end cap marked:

MAXIM SILENT FIREARMS CO.

NEW YORK

PATENT MARCH 30, 1909

The original retail price of the Model 1909 silencer with coupling and barrel sleeve was $5.00. Also shipped with the silencer were instructions for threading a barrel. There were no federal restrictions on the purchase of a silencer, they were sold at hardware stores, sporting goods retailers and factory direct through mail order, they were available to anyone. Factory orders were shipped through the U.S. post office directly to the customer in a cardboard tube. Maxim’s Model 1909 was superseded by the new Model 1910 introduced in an undated letter printed by the Maxim Silent Firearms Company, main office and factory, Hartford, Connecticut. Two of the advantages of the 1910 Model were it was smaller and lighter than the Model 1909. The flyer announced that the price for the 1909 Model was reduced to $3.00 “while supplies last”. The eccentric shaped 1910 suppressor has an overall length of 4.5-inches and a diameter of 1-inch. There are 13 baffles inside the tube. Maxim’s new eccentric tube was designed so that it would not obscure the shooter’s view of the host firearm’s sights. The retail price was $5.00 for the .22 caliber model and $7.00 for the centerfire version.

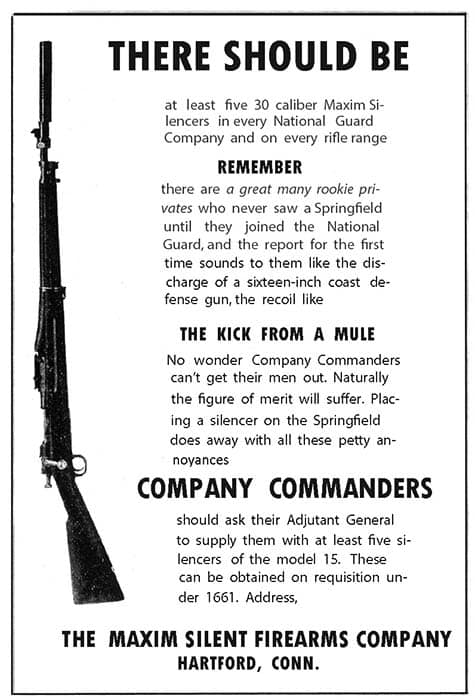

In addition to .22 caliber silencers, other larger caliber units were available, including a Model 15 called the “Official U.S. Government silencer for the .30 caliber M1903 Springfield rifle.” The use of the Maxim silencer was considered by the U.S. Army for training new recruits, who were often intimidated by the report of the 30’06 service rifle, causing them to flinch and experience temporary hearing loss. Reportedly, a small number of the Model 15s were purchased by National Guard Units. The silencer was tested by the Army at the Frankford Arsenal. According to the Frankford report; “The unit was 9-inches long and 1-inch in diameter. The silencer attaches to the Springfield rifle by an adapter with two half sleeves and a nut. The inside of the Maxim silencer is composed of an initial expansion chamber, followed by nineteen equally spaced baffles. The baffles are indented rearward and off-center from the silencer and rifle bore axis.” The Maxim Silencer Company often boasted of the government’s use of their silencer in their advertising, as a testimonial to promote sales. Cost of the “Government Model” silencer was $8.50.

The Maxim Company offered many different couplings designed for attaching silencers to the muzzles of firearms that did not have threaded barrels. For .22 up to .32 caliber there was a coupling designed to be driven (with a mallet) onto the muzzle end of the barrel. For rifle calibers there were clamp-type and sight-type couplings. The clamp type simply clamped around the barrel and was secured by a screw. The sight-type required the front sight to be removed and the coupling driven onto the barrel until the muzzle was firmly seated on the shoulder of the coupling, then the sight was to be reinstalled. Shims were provided to insure the couplings were a tight fit. The end of the couplings were threaded for attaching the silencer. The Maxim catalog included a list of couplings available for a number of manufacturer’s .22 caliber firearms. The drive-on couplings were $1.00, the clamp and sight type couplings were $2.50 each. Extra shims were 25-cents per set, thread protecting caps 25-cents each. The Company recommended that on hi-power rifles and those with octagon shaped barrels that the muzzles be threaded. The Company offered the threading service for $3.00.

After the 1910 Model, the Model 1912 silencers were introduced. The Maxim Silencer Company introduced many new silencers through the years, but it appears that subsequent models were all based on the eccentrically shaped Model 1910. Maxim’s silencers were effective in reducing the sound signature of firearms even by today’s standards.

During World War I, the Maxim Silencer Company produced silencers for the United States Armed Forces snipers and sharpshooters. In 1912 Maxim incorporated his business as the Maxim Silencer Company. During World War II, the company produced engine-exhaust silencers (mufflers) for tanks, submarines and other vessels. After the war, the company focused on manufacturing seawater-distillation units for ships. The company also produced snow blowers and automobile mounted snow plows.

Hiram Percy Maxim is credited with fifty-nine patents. Maxim was also passionate about aviation, sailing and radio. He served as chairman of the Hartford Aviation Commission and aided in the construction of Brainard Field, a municipal aviation port in Hartford. He developed the first practical seawater evaporator for providing ships with fresh water. He operated an amateur radio station out of his home and co-founded the American Radio League.

Maxim was not the only inventor in the family; his father Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim (1840-1916) invented the Maxim Machine Gun and his uncle Hudson Maxim (1853-1927) was the inventor of smokeless gunpowder. Maxim married Josephine Hamilton, in 1898. The couple had two children, a son Hiram Hamilton Maxim (1900-1992) and a daughter, Percy Maxim Lee (1906-2002). His son was also an inventor and his daughter was an active civic and political leader. Both Maxim and his son worked on improving the portable Ham radio. Like his father, Hiram Hamilton Maxim attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Upon graduation in 1921 he returned to Connecticut to work at the Maxim Silencer Company. When Hiram Percy Maxim died in 1936, his son, H. Hamilton Maxim took over as President until his retirement.

In 1934, the National Firearms Act was passed, the new law did not ban machine guns or silencers outright, but imposed a hefty $200.00 tax on the transfer of them. The tax took a large toll on machine gun sales and killed the market for silencers. Sound suppressing devices are required by law on vehicles, lawn mowers, and other devices to keep them from annoying the public, and to protect the hearing of the operators, but to reduce the sound signature of a firearm you have to pay a special tax that often exceeds the price of the silencer itself.

In 1956, the Maxim Silencer Company was sold to the Emhart Manufacturing Company. Today the company operates as Maxim Silencers Inc. out of Houston, Texas as part of IAC Acoustics. The company manufactures a complete line of noise control, waste recovery and emission control equipment under the Maxim trade name, though they do not manufacture firearm suppressors.

While a few major firearms manufacturers offered factory threaded barrels for Maxim’s suppressors, most firearms of the day with threaded barrels were rare.

The rifle featured in this article is a Winchester Model 1890, chambered for the .22 Long cartridge, was special ordered in 1913 with a factory installed Maxim Model 1912, .22 caliber suppressor. The buttstock tang of this rifle was stamped with the word “Special”, a marking normally found on high-end Winchesters. At some point in this rifles past the cartridge lifter was altered by the addition of a roll-pin to convert it from .22 long to .22 short cartridges. Both rounds use a 29-grain bullet, thus accuracy was not affected. Available .22 Short and .22 Long ammunition of the period remained at subsonic velocity in rifle length barrels. The rifling in older rifles designed for .22 Short and .22 Long ammunition is 1 turn in 18-3/4 inches. Rifles chambered for .22 Long Rifle cartridges have a 1 in 16-inch twist to stabilize their heavier 40-grain bullets. Modern high-speed .22 cartridges were not developed until 1930. Much of the .22 caliber ammunition available during the period was corrosive, the first non-corrosive .22 Shorts were developed by Remington in 1927. The silencer cleaning procedure recommended by the Maxim Company was to “Use a good nitro-solvent oil or soak overnight in warm water, rinse and dry quickly on a hot surface to evaporate the water inside. Then oil thoroughly with a good gun oil”. Failure to follow the cleaning instructions resulted in the premature demise of many Maxim silencers that were made of mild steel, and is part of the reason they are rarely encountered today.

The standard barrel length of a Winchester 1890 rifle is 24-inches. An original factory threaded barrel on an 1890 Winchester had the threads cut prior to machining the dovetail for the front sight. If the barrel was threaded after it left the factory, front sight would have to be moved rearward, and a new dovetail cut made, and a dovetail blank would need to be installed to fill the void in the original dovetail, assuming that the barrel was still 24-inches long. During production custom barrels were available in even numbered lengths from 14 (pre-National Firearms Act) to 30 inches, at a cost of fifty cents per each 2-inches.

Times have changed, and more people have moved from the congestion of the cities to the suburbs. To remain accessible to their customers many businesses have also relocated to suburban malls and strip malls. This phenomenon is commonly known as urban sprawl and it is occurring all over the U.S. As urban sprawl continues there are less and less place to shoot without disturbing someone. In a few cases, sportsman’s clubs have been forced to close their shooting ranges after housing developments have sprung up nearby. Despite the fact that the range existed long before the housing, it isn’t long before the home owners start complaining about the noise. In modern times gun owners are facing the same situation their city dwelling counterparts had many years before.

The current popularity of suppressors today is perhaps related to Maxim’s original idea, to enjoy shooting discreetly and without disturbing the neighbors.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V20N3 (April 2016) |