By Seth R. Nadel

In the late 1800s, the manually operated “automatic gun” was the state of the art. The Gatlings, Nordenfelts and Gardners were adopted in very limited numbers by the major armies, with the U.S. choosing the homegrown Gatling.

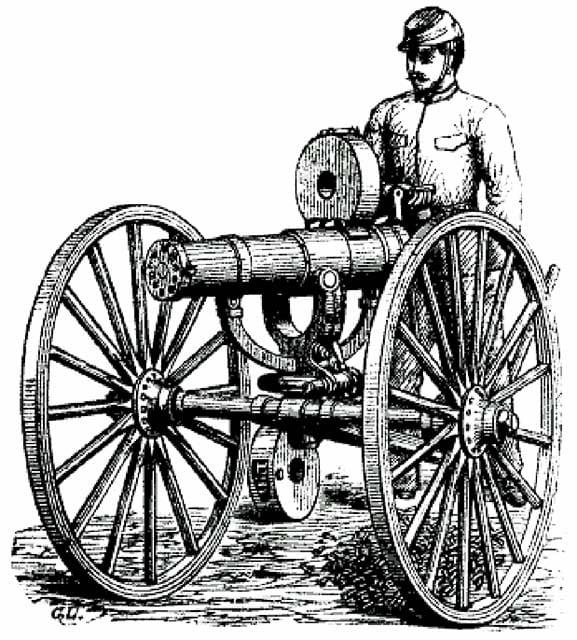

All of these guns were large, very heavy and mounted on either pedestals for naval use or large wheeled carriages like the artillery of the Civil War. Since they looked like artillery, they were grouped with the artillery and used like artillery, fired well back from the front line of the infantry.

Then, at the start of the Spanish–American War in 1898, a chance meeting and a bowl of ice cream changed the employment, the look and the design of all fast-firing guns—manually-operated and true automatics.

The principal player was John Parker, a recent West Point graduate, a lowly 2nd Lieutenant. There was at the time no retirement system, so officers stayed until they died, stifling promotion for the lower ranks. Parker was introduced to the manually-operated, multibarreled Gatling gun and quickly became an enthusiast, even though he was an infantryman.

Our War with Spain

When the Spanish–American War started, we were, as usual, woefully unprepared. Our Army was way too small, and no one had commanded a Naval invasion since the war with Mexico, 50 years prior. Our Navy had little in the way of troop transportation and no real landing craft; just ships, boats (mostly powered by oars) and rafts. Troops were enlisted for the duration, most famously the 1st Volunteer Cavalry known as the “Rough Riders,” lead by Lt. Col. Teddy Roosevelt. They play a part in this story as well. For all the troops, there was stiff competition to get space on the few transports going to Cuba.

Lt. Parker got permission to take four Gatling guns—IF he could get onto the transports. Lieutenants did not usually speak to Generals, and General Shafter was really busy with trying to organize our first large invasion. Parker wanted to get into the fight—and so did everyone else. Tampa was jammed with far more troops than there was room on the transports. He contacted various senior officers, without progress.

He ran into a young 2nd Lieutenant who happened to be the Ordnance Officer for the invasion and thus could speak directly to the General. They retired to a local ice cream parlor, where Parker made his case. The Ordnance Officer decided to help and talked to General Shafter. Parker was temporarily assigned as the “Deputy Ordnance Officer,” and his guns and men were put on the transports.

General Shafter gave some very general orders to Parker, who “took wide latitude” in interpreting them. Rather than placing his Gatlings in line with the artillery, to be used for indirect fire (where the gunners could not see their targets), he took them up close behind the troops about 20 yards behind the firing line of infantry and dismounted cavalry, which included the Rough Riders. He did not expose them until the Spanish refused to surrender, and the charge was ordered. By this time, he had been joined by Sergeant Tiffany of the Rough Riders, who had two Browning M1898 machine guns and 14,000 rounds of ammunition. They supported the charge by pinning down the Spanish troops. They also shot many as they left their trenches to avoid the steady hail of bullets. The attack by the Rough Riders and the 10th Cavalry (all dismounted, as there was no room on the ships for horses) was successful. After taking the heights, he had his troops remove the wheels from the Gatlings to lower their silhouette so they could be emplaced in the trenches.

Thus the Beginning

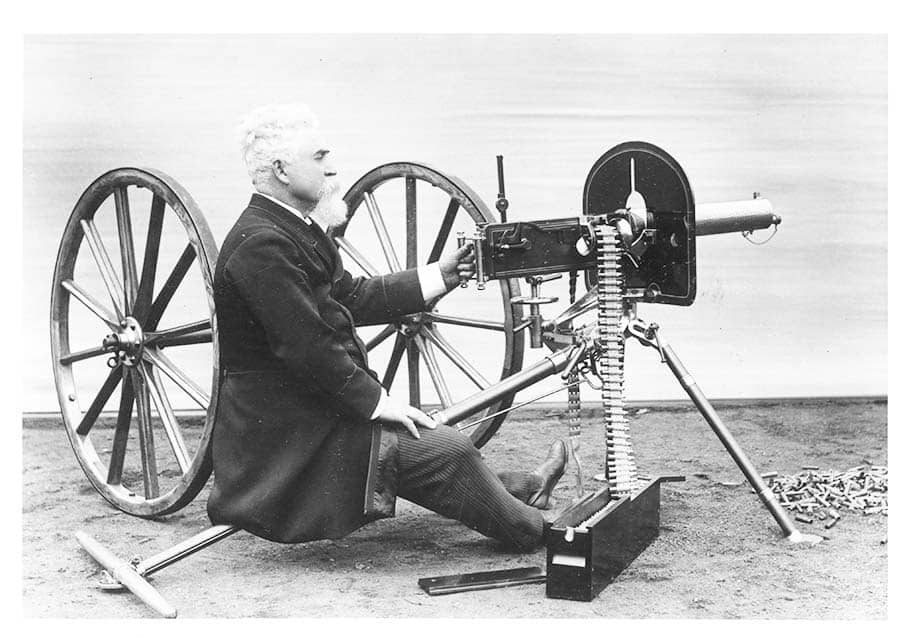

We see here the start of the trend that still continues. Early pictures of Gatling guns on their wheeled mounts show the crew members standing to serve the gun. The pictures of Hiram Maxim, with his automatic (not manual) gun number 1, show him seated and sitting upright on the tripod. All the belt-fed guns used in WWI similar to our Browning M1917 had tall tripods about 24 inches high to the bottom of the receiver. In WWII, our basic belt-fed Browning M1919A4 had much lower tripods, lowering the height to 10 inches to the bottom of the gun, so the gunner could be prone while firing. Crews became smaller: from 10 for the Gatling to five for a 1917 water-cooled and then the WWII 1919A4 (air-cooled), which still required a team of three (the gunner, who carried the tripod; the assistant gunner, who carried the gun; and ammo bearer(s), with 250-round cans). Today, one or two soldiers serve the gun.

The Germans in WWII had adopted a machine gun that looked more like a rifle, so the gunner could get even lower and fire off of a bipod—or off of a very sophisticated tripod that still sat up high.

The weight also dropped, from 170 pounds of a Gatling (gun without mount), to 41 pounds of the Browning M1917, to the 31 pounds of the WWII 1919A4. Today, our troops carry belt-fed machine guns that weigh less than 30 pounds (23 pounds for the obsolete M60) and can be handled by one soldier.

Machine guns were assigned to machine gun Battalions in WWI and were parceled out to lower units. By WWII, machine guns were placed in platoons, and by Viet Nam they were used in squads. Today, they can be found in even smaller units, another trend started in Cuba by Parker.

And the Gatling still serves in the guise of the Vulcan 30mm cannon, the gun chosen for the Air Force’s A-10 Warthog close air support aircraft, the “mini-guns” (in 7.62 NATO) on AC-130s and various helicopters and ground mobility vehicles.

Parker (known ever after as either “Machine Gun Parker” or “Gatling Parker”) was still serving in 1917, when Colonel Parker was made the head of all Machine Gun Schools for the American Expeditionary Force in France. He must have been a “hard charger” to rise from 2nd Lt. to Colonel—5 grades (1st Lt., Captain, Major, Lt. Colonel, Colonel) in 19 years, when some officers were Captains for decades.

Parker was well aware of the potential impact of what he had done. In his book, History of the Gatling Gun Detachment at Santiago, he notes that machine guns could, and should, be used in the offense. In fact, he states that the infantry and artillery had been “pounding away” at the Spanish for 2 hours, yet 8 1/2 minutes after the Gatlings opened fire, the enemy trenches were captured. He even submitted a proposal for the Gatlings to be considered a “new arm” of the service, separate from the artillery.

And to think this all started over a bowl of ice cream—the flavor and toppings of which are lost to history.

Oh, yes, that young Ordnance Officer whom Parker convinced over ice cream? You may know his name, as he rose to the rank of General and then after WWI promoted a handheld machine gun, which he coined a “submachine gun.” That was John Taliaferro Thompson, the promoter of the Thompson submachine gun.

SOURCE: The Gatlings at Santiago: History of the Gatling Gun Detachment at Santiago, U. S. Fifth Army Corps, During the Spanish-American War, Cuba, 1898. John H. Parker.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V23N8 (Oct 2019) |