Last week on SAR.com, we had the first part of the Interview with Henk Visser. We broke off the conversation with Henk as he started the discussion about the Stoner 63 system and his involvement with the rifle grenade projects.

SAR: You were now out of the picture with CETME as well as the new Heckler & Koch…..

Visser: Out of the business picture yes, but I still had many contacts. I had contacted Gene Stoner in America, and we became good friends. This was in 1962 I believe. I told him everything that happened in Europe. There was a sales director named Paul Van Hee from Cadillac Gage; the company that had paid for the development of the Stoner Rifle in Newport Beach, California. Nothing could be done without Cadillac Gage over in Detroit being involved. I went there, and in the end I managed to make the right contacts. Around that time, I sold NWM in Holland to a German group, the Quandt Group, that was Mauser, BMW, Mercedes, Nico Pyrotechnik, etc.; the whole thing. I became the director for their military business. They also had a product that was barbed wire with razor wire on it and the wire is steel based. If a tank runs into this concertina, it wraps around the tracks. The Americans were very interested in it because this razor wire – you really don’t want to touch it. Cadillac Gage got the contract to make that wire in the States, and we got the rights for the Stoner rifle system in the whole world outside of America and Canada. Gene was a genius in designing these guns; a brilliant technician. There were things we wanted to change; you had the gun, and you’d shoot it, and your fingers would hurt afterwards. It was somewhat complicated to change parts and the cocking handle on the MG could only be used from the right side.

SAR: When you say the cocking handle is wrong, what do you mean?

Visser: In the end we made it underneath, so that the left or right handed person could use it easily. Anyway, Gene got interested in other things, and I hired Hans Sturtz, a German who worked for Gene Stoner. He was fantastic at making things….he worked for us in Holland, and we changed the Stoner rifle in various ways, small things, but important, like a good folding stock – one that locks. We made a good bipod too, a sturdy bipod, one that locks on the gun. I kept all of the documentation about what we did. We made a barrel with flutes, a thicker barrel, and we arranged for the sling swivels on the right place.

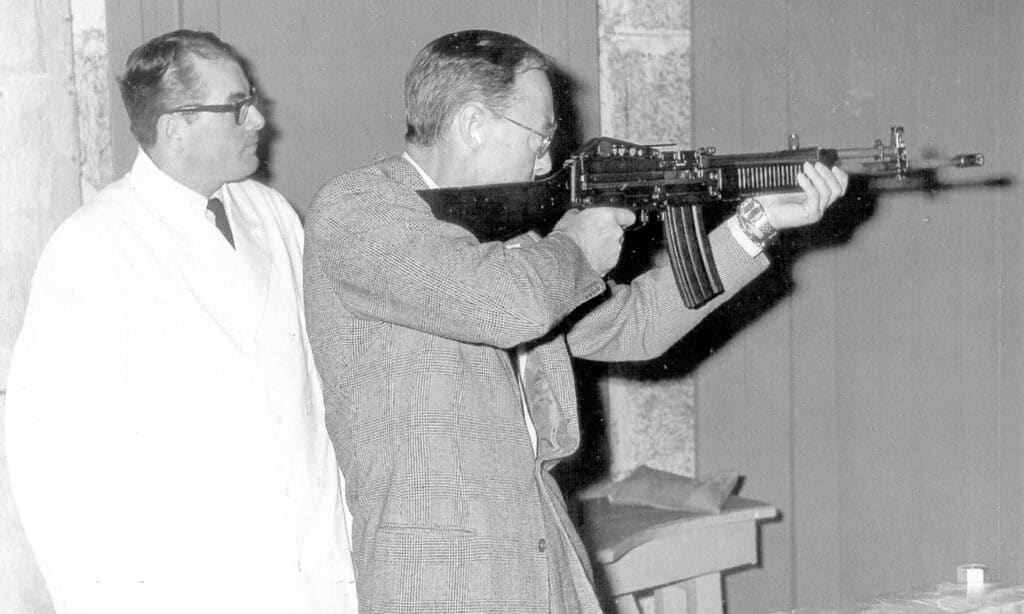

SAR: This is the Stoner 63 we are discussing? Let me go get some examples from the vault. (Dan gets some Stoner 63 and 63As to put on the table for Henk to point out things.)

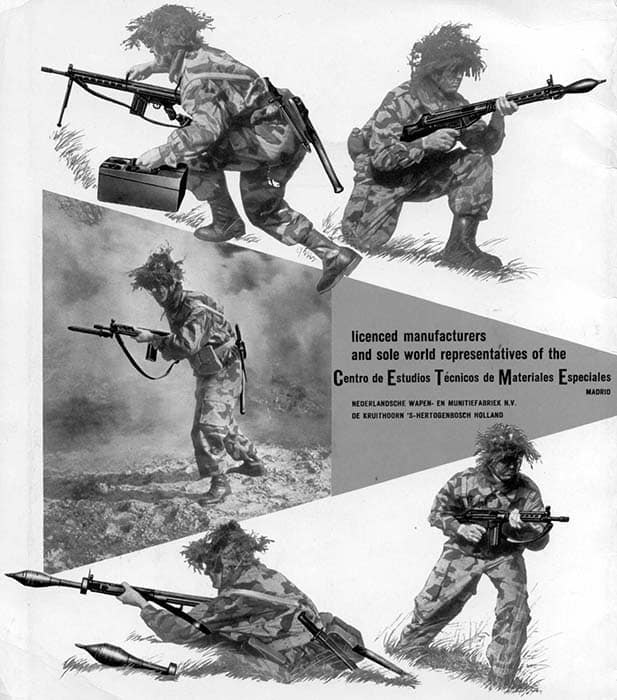

Visser: Actually the 63A but improved. We did several things for the 63A. This was now the 63A1 when we were done with it. As I said, we improved the bipod and made it mount on the rifle, which was my idea. In the beginning, Gene Stoner didn’t have a flash hider with the right dimensions for the international rifle grenade launching requirements. The original CETME was even missing that by design. They just had a barrel sticking out making a hell of a flash, and noise. I designed the flashhider for the CETME (G3). We changed the Stoner 63A to be able to fire Rifle Launched Grenades (RLG), a very important feature even today in many armies. We changed location of the charging handle, the bipod, the stock, and many other minor changes.

SAR (Dolf): Henk, I thought that originally you were involved with the AR-10, with the 7.62 Stoner rifle?

Visser: No, Dolf, I have heard this before but I had nothing to do with that. The AR-10 was our competitor, the government plant Artillerie Inrichtingen (AI) at Hembrug, in Holland. They got so upset that we had the Stoner 63A license – first we had the CETME rifle then the Stoner – that when the Director of AI read in TIME Magazine about this lightweight rifle from ArmaLite, he and his secretary got on a plane and flew to Costa Mesa to make a deal on the AR-10. He was not liked by the Dutch generals because of the way he treated them. In reality, the AR-10 was a fantastic rifle for 7.62 NATO. Director Jungeling invited all the top generals to his plant and they were getting coffee and cake, and while they were eating he reached next to his chair and holds up an AR-10 and announces, “Gentlemen, this is your new rifle! This will be the future!” Those generals decided at that moment in their minds that nobody was going to adopt the AR-10. They didn’t want to be told by a civilian what would be the new Army rifle. He killed it with that. It’s a very sad story because it was a good rifle. They wanted to do their own testing and make their own decision and like most generals, they do not like anyone telling them what they will have for weapons.

SAR: You had the rights to the Stoner 63 outside of the United States?

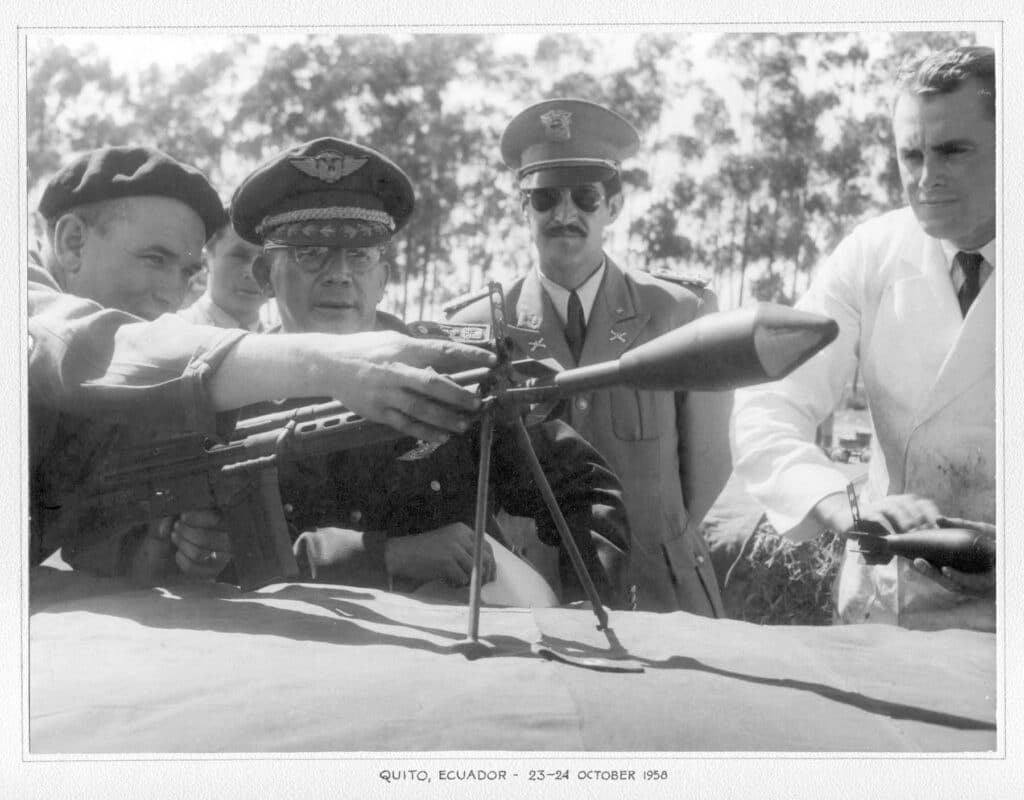

Visser: Outside of United States and Canada. We had a very optimistic view of our opportunities because we and Cadillac Gage thought that the US Marines would adopt the system. We took the Stoner Rifle to Ecuador, Chile, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Germany and, Israel. I went everywhere. We spent millions, and I told the top people in my company, “This is it. This is what the soldiers want.” I never told the customers that – I simply showed them the quality and let them test the rifle. Standardization, a cheap machine gun…the main parts are all the same. Maybe I overdid it a little bit at times. We had the Inspector General of all of the forces in Holland and his Royal Highness Prince Bernard; he had seen it and liked it, and he tried to push it in NATO. Again, I think maybe there was too much support in this way, these guys all wanted to do it themselves and make their own decisions. I was instrumental in the standardization of the rifle grenades as well. Because of me, all of the rifles have the flash hider with the 22mm diameter. I was close with MECAR in Belgium, and we developed a whole series of rifle grenades, including a new small hollow charge which would puncture a 5cm hole in a steel plate at 160 meters.

SAR: So this was a shaped charge system. What was the launching platform – bullet trap, bullet through or launching blank?

Visser: It was a special blank cartridge at the beginning. We had, even for the Stoner, a short magazine that was colored green that could be loaded with this gas cartridge, so that there would be no mistake of putting a live cartridge in the gun.

SAR: Did you get any sales of the Stoner 63A1 in the countries you just mentioned?

Visser: The biggest thing was that the United States Marines were going to adopt it. I was at Quantico almost weekly, and they wanted these, so after the first lots of prototypes they ordered 3,000 or so from Cadillac Gage and shipped the Stoners to Vietnam. They wanted a live combat environment to test them. The Stoner was very successful and the Marines liked it. Then the U.S. Army stepped in and said, “No. We will all have the same weapons. You take the M16.” The Marines got mad, and talked about bent barrels and this and that, and the cocking handle they did not like and the rifles needed a heavier barrel, etc. We were offering this gun that we demonstrated as the future U.S. Marine weapon. We really pushed that, you know? Because who was this tiny little company in Holland, and Cadillac Gage was not known either: they made a few armored cars. Nothing to show manufacturing ability with small arms, but the Marines with Stoners, that was another story and it was our sales pitch to our customers.

Gene Stoner was very bitter about many of the issues that occurred then. In the Stoner 63 rifle he had tried to fix what he saw as the problems in the M16, which was also his design originally.

The big blow was when the decision came that the U.S. Marines were not going to take the Stoner system. This made it difficult for us, because the people we were trying to sell it to thought something must be defective with the guns since the U.S. was not adopting it. I had sold 12 to Singapore after a demonstration and sold some to Thailand, Japan and South Korea. We were a nice company, we didn’t bribe anybody. The same in the Philippines. I still remember the offer for the Philippines. We had trained them so that they could work on the guns themselves. It was a $35 million deal. Then Colt got in and they got the order instead for $58 million. Their agent had better “contacts” – almost $20 million extra above what our program was. I was with the top man there, the commissioner, and if I had said that we could raise it to $55 million or whatever, we would have had that deal. But that would have never occurred to me. The same thing happened on the deal in South Korea.

The Stoner is an excellent weapon, and the only complaint I ever had was that if the soldiers have the rifle, and then they give the company armorer some cigarettes or something, they’ll quickly have a belt-fed and a heavier barrel, and before you know it everyone in the whole group has a machine gun. (Visser laughs.)

SAR: That’s a complaint? If they trained a platoon with all belt fed Stoners, it would have been pretty formidable.

Visser: Yes, but these armies aren’t trained that way. Riflemen should be riflemen, and the machine gun is restricted to certain personnel with specific machine gun jobs. It would have been very simple to make things so that you couldn’t make a machine gun out of a rifle, but that would get rid of one of the beautiful things about the Stoner – the adaptability. The only complaint I ever received was that it was too easy to make a machine gun out of it.

SAR: Henk, you were involved in many of the post World War II arms deals. What about the surplus deals?

Visser: I got some surplus 20mm ammo from our Air Force and I sold it to Israel. I worked with Tom Nelson’s company and went on some trips with him, but we were not very successful in obtaining surplus guns.

SAR: Was there any surplus in your time in Vietnam?

Visser: Only the RPGs and other items we discussed earlier. Of course there were much more US military leftovers from Vietnam that were surplused out, but not through our company. I should tell you that I was given the rank of Colonel in the US Army so that I had an ID card. If you got captured by the North Vietnamese, the US Army figured that an officer would be treated better. I still have the ID today. (Henk shows us a Vietnam era US Military ID card with his picture and the rank of Colonel.) We wanted to know how the testing went with the 3,000 guns for Vietnam, but secondly we had to be involved in the MECAR rifle grenades. The Marines were very interested in these rifle grenades, the shaped charges that punched 5cm holes. There was one demonstration where the armored plate was at 160 meters, and as I was a good shot, I could stand there and whop it, and they could see the hole was there. I came upon the idea of mini hand grenades then. In Vietnam, I saw the soldiers go out with only two hand grenades, and if the grenades got wet then they had to be destroyed. With the help of MECAR, we made very small hand grenades and the inside was ribbed in little squares. We used RDX instead of the normal high-explosive. I designed a special short ring that you couldn’t pull, you had to twist it, and then you could get it out. This prevented a lot of accidents. I had a special detonator made by Dynamit Nobel and we sealed the grenades in plastic so you’d have a bandolier with ten mini hand grenades. This weighed as much as two standard hand grenades giving the soldiers a lot of waterproof hand grenades for their missions. I also had them make an aluminum tail with an old-type beer bottle closer; you could stick the hand grenade on there and close that. There was a thin wire, so when you fired it from the rifle, the wire would break and the lever would jump off and at 200 meters you had an explosion.

Then MECAR said, “Nice, but let’s make a rifle grenade that’s just the same in arming, but the standard size.” We also had parachute flares. Then there was a request from the Americans and they said, “Listen, we have had cases where we bombed our own people in the deep jungle cover. We want a flare that goes through the canopy and explodes at 100 meters with a big flash and a brown cloud.” They wanted a test quantity of 200 or so, and three weeks later they were on a plane from Germany to Vietnam for testing. It was really successful; there was a big flash and a bang after it exited the jungle canopy. We were working to design a bullet trap in the grenade tail so you could fire with live rounds. Around that time the owners of MECAR decided to sell the whole shebang to an American company. I had a contract with them that said I received a commission on everything that was sold, regarding the rifle grenades and such. They tried to talk me out of it, and I said, “Gentlemen. You’ve just told me that I am going to make millions from these mini-grenades, but give me one hundred thousand dollars and it’s yours.” I wanted out of the company and the new owners. A lot of yak-yak and I got my hundred thousand dollars.

SAR: But not the millions in the future…

Visser: No, I would get none of that. The Marines bought a lot of those rifle grenades, and they tested them and decided to adopt them. Again the same thing happened. The U.S. Army was working on the 40mm launchers and they didn’t want the Marines to have something else. The Marines adopted the 40mm, not our multi-purpose hand and rifle grenades.

SAR: That sounds like the end of the Stoner 63 and MECAR projects. Where did you go from there?

Visser: We were into developing a “breakup” training round. It was an idea that I had in Germany after seeing how they had to have tremendous ranges when they were shooting at air targets. We had a plastic bullet with compressed iron powder parts in it that gave the same recoil – everything the same as a ball round, but it caught the rifling and because of the plastic jacket, after 50 meters or so, it would burst and there was just a cloud of powder. What they also wanted to test was putting a round that wouldn’t function in the magazines; something which would cause a stoppage. It was for the soldiers learning to fix the stoppage. We sold millions to the Germans. Really, many millions in numerous calibers as it turned out. This ammo functioned perfectly in the German 20mm gun and the twin 20mm AA guns.

They had thousands of these twin-barreled 20mm guns used for AA defense and the troops had to train with them. For training purposes, a plane came flying past with the target sack. They had to aim and they fired like mad and it was really something exciting to see: a whole row of twenty twin 20mm guns. From there we went to the 40mm Bofors round 40 l 60 and 70, also with the break up projectile.

One problem occurred when the Dutch Navy wanted the 40mm Bofors too. They went out and shot it at sea, but there was so much wind out there that the powder would blow back and immediately started rusting the ship. “Oh my God, our beautiful ship! You are ruining our beautiful ships” they cried. (Laughter.) For land based use, though, we sold a lot of these.

Around that time the Swiss company Oerlikon asked me to come and work for them. Singapore asked me to get them 120 20mm cannons for the armored cars they bought from Cadillac Gage. I just walked in to Oerlikon and said, “They want an order from you for 120 cannons.” Oerlikon couldn’t believe it. They had never done much business in the Far East, only Japan. I got the offer and flew out to Singapore. They looked at the prices and thought it was ok, and they went up to the boss, who had a Dutch name, and he signed the contract. I was amazed. I came back and walked into Oerlikon and said, “Here’s your contract.” They almost fell over. After the war they hadn’t had any big contracts like that, 120 20mm guns. The big boss said to me, “What do you want as a commission?” I hadn’t even thought about it. I thought, “Maybe one percent? Do I have the guts to ask for two percent?” Then the boss says, “Is six percent enough?” I got a million Swiss francs commission, and that was the first time I’d ever done anything like that. I started working for them and became the boss for the whole Far East. I sold the South Koreans all of their 35mm AA guns, and also sold to Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand. That made me a rich man, you know, because besides the big salary they paid me a two percent commission as well. When you get a $900 million order, that’s really something. (Laughter). I was with Oerlikon for about fifteen years, from 1975 until around 1990.

SAR: Not bad for a little Dutch kid who started his cannon ammunition career making 20mm detonators while a slave laborer in a German prison.

Visser: Yes, a very, very, long way from that.

SAR: What are you working on today?

Visser: I spend most of my time working on restoration of historical firearms, major projects to save many of these works of art. There was a big restoration project in Russia. I came to Russian in 1988 with Dr. Arne Hoff, the director of the Tojhuseet museum in Copenhagen. Even before the war, it was known there were many historical Dutch guns in the Kremlin Armory. We went there, and we were received well but they didn’t even want to give us their last names. It was forbidden to give your last name to a foreigner. I liked them, and they liked me, and we got off on good footing. Each time I came there, I brought them suitcases full of Dutch specialties of coffee, “cup-a-soup” packets, an electric water heater, and 200w light bulbs. They had 40w light bulbs in the depot and you couldn’t see anything. I brought them nice mugs to drink from, and we had a very good relationship.

I knew all the guns they had, and they had about 350 beautiful guns, of which 120 needed serious care. Pieces were broken off, pieces to be repaired, and I asked, “Why don’t you restore them? You have a lot of wonderful pieces here.” They said, “We have no money to do this, Russian things must come first.” I said I would do it and would pay for it. It took two years of negotiation, and I became friends with the Minister of Culture, who must have studied at an American university because he spoke fluent English. They eventually let 120 guns go to Holland where I could have them restored. We had the best restorer in the world for antique arms, Herman Prummel, he can do anything. I thought it would be half-year project, but it took two and a half years to finish. In the meantime, a good friend of mine, Helena Yablonskaya, wrote up all the Dutch guns in Russia; about 120 at the Kremlin Armory, some at the Historical Museum, some at St. Petersburg’s Hermitage, 350 in all. In the series of my books, there is one book about all of those.

SAR: It sounds like you are very dedicated now to restoring these historical Dutch firearms.

Visser: Yes, very much so. I am full of crazy stories on this. When I was younger, before the war, our high school made day trips to different places. One of the trips was to Emden in North Germany and there was an armory in the Rathouse with lots of suits of armor and guns and pistols. The first battle with the Spaniards in our Eighty Years War was in 1568 in ‘t Heiligerlee, a village near Groningen. There was a wooden case closed with mesh steel wire, and inside it were musket balls from the first battle to get rid of the Spaniards. We had a Nazi guard with us in a black uniform, and when he wasn’t looking I took my pocketknife and lifted up the steel wire and stole one musket ball. I still have it today. (Laughter.)

Emden was flattened during the war and I always wanted to go back. I went to the Meppen Army testing grounds nearby, but I never got to go back to Emden. Finally, about a year and a half ago I go with Herman Prummel who told me that a lot of pistols were rotting away in the depot. I went over there….and it was horrible. There were the most beautiful Dutch wheellock pistols full of wormholes, half the stock gone, and the metal cleaned with emery paper. My big mistake was not to take the whole pile for an offer of 50,000 euros because they’re never going to show this stuff, but I said, “Why don’t you restore them?” They said they had no money, so I said I’d do it. They said, “Why don’t you take them? We’ll talk to the director, and come back in two weeks.” So I came back in two weeks and instead of having 10 ready, they had 50. We took all 50, and it took more than a year for Herman Prummel to restore them. They are in fantastic condition now. Fortunately, they had saved all the metal parts that had fallen off. If the buttstock had been eaten, they still had the metal ring. Those Dutch wheellock pistols were very light and elegant. These are at my house right now, waiting for the museum to open. We are now working on a catalogue with pictures of them.

I guess that my passion today is the works of art that are in these old firearms. I have spent a lot of time making them whole again.

SAR: Henk, I want to thank you for sharing these stories with SAR’s readers.

Visser: Yes, I have enjoyed this, and I hope to come to the SHOT show and see old friends.

We discussed many more stories of the old days and the arms trade, as well as current restoration projects that Henk Visser is involved in, but those must wait for another day. – Dan

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V9N7 (April 2006) |