By George E. Kontis, PE

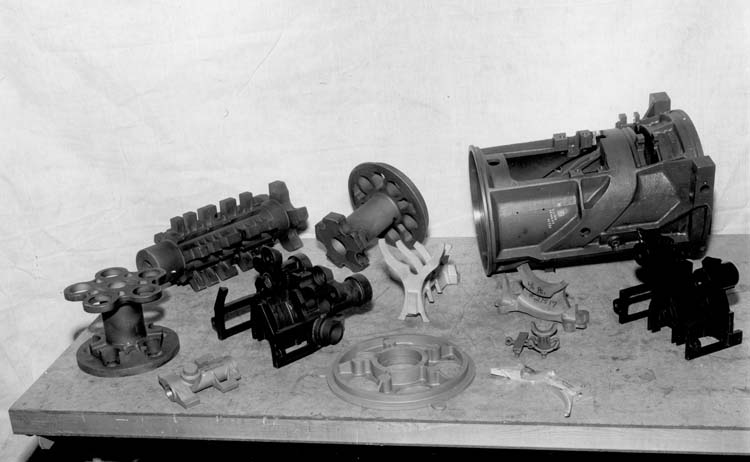

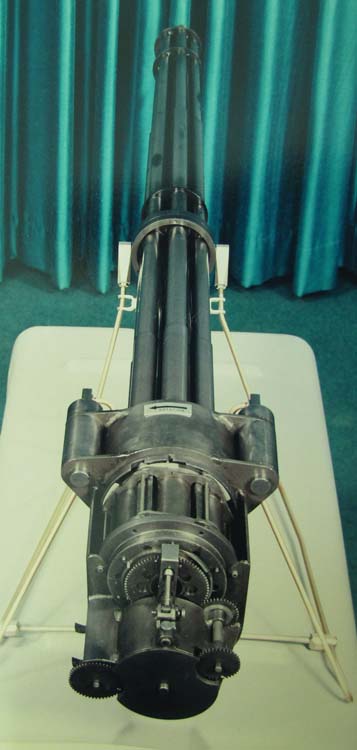

During the last century, John M. Browning gained well deserved prominence in the field of firearm design. None have been able to equal his record for developing a wide variety of novel gun systems. There is one individual who stands out as the developer of not only guns, but some of the most varied and unique ammunition feed systems. That man is Lewis K. (Lew) Wetzel. He began his career at the General Electric Company working on the final development and first production of the M61 20mm Gatling gun. The high rate of fire capability of this new externally powered weapon was unprecedented and would not have been successful without flawless storage and feeding of the ammunition. It required screw conveyors, sprockets, carefully machined guides, and complex geometrical shapes to guarantee perfect round control throughout the cycle. Perfecting the ammunition storage and feed was as important as the development of the weapon itself in the achievement of their legendary high reliability.

GE assigned engineers and mechanical designers for these developments, and these teams usually had one common denominator: Lew Wetzel. From linked feed fed from ammo boxes to complex linkless feeds, Lew Wetzel distinguished himself as the premier designer. What resulted from his efforts and those he directed as a manager was a high level of gun and feed system reliability never before having been achieved.

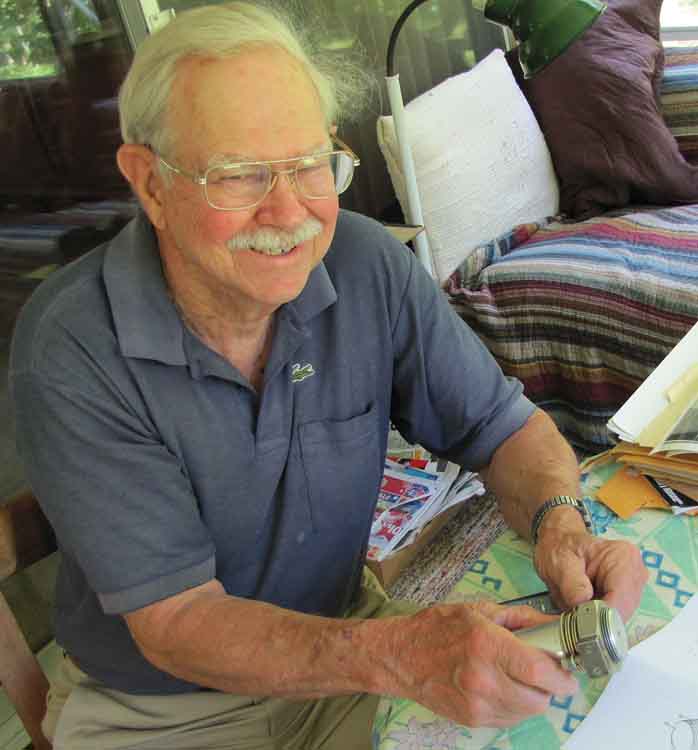

During most of my 15 years at GE Burlington, I worked for or alongside Lew and gained valuable insight into his techniques for design, analysis, and testing. I recently called Lew and asked him if he’d consent to do an interview and was glad he accepted.

When the General Electric Armament Systems Division took over the Bell gun turret factory in Burlington, Vermont, a new era had begun in the design of high speed cannons and machine guns. GE transferred the ongoing development work for the M61 from a New York plant to the Burlington, Vermont facility. This was to be the first production of an externally powered Gatling gun. Success of this cannon was important to arm future fighter aircraft on their way to fight a new war in Vietnam. In this war, 20mm cannons armed jet aircraft, and 7.62mm Gatling guns were invaluable in helicopter and fixed wing applications. GE Burlington could only meet these urgent wartime needs by hiring top engineering and manufacturing personnel. The company quickly rose to significant prominence as a weapon designer, developer, and producer, and Lew Wetzel was one of their most prized secret weapons. We met at Lew’s house in Colchester, Vermont:

George: Tell us, Lew, where are you from and where did you go to college?

Lew: I’m originally from Michigan, but I studied engineering in an Ohio school, Antioch College. I fell in love with the school’s co-op program, where you alternate semesters between work and classes. It’s great because you can work in a field before you spend four years learning it and then decide that’s not what you want to do for the rest of your life. You make contacts and find job leads too. It was an excellent school with a well-rounded curriculum. I had some interesting jobs and classmates including Corretta Scott King and Rod Serling – the guy who created The Twilight Zone. I knew them both very well. Rod had started a campus radio station. I was a nerd then too, and I helped him build some of the equipment. He was the nicest guy you will ever meet. He graduated a year ahead of me.

George: So when did you start a full time engineering job?

Lew: It was right after the Korean War and they were still drafting people. GE and a lot of other companies came in to recruit. They explained their engineering test program and the opportunity to get critical skills draft deferment. I didn’t want to go back to Michigan. The test program involved three month assignments in different GE locations. I figured it would be interesting and I’d get around the country. I went to the Ohio, Evendale plant and worked in jet engines. After three months I put in GE-Burlington as my third choice and was a little disappointed at not being selected for the other two. But, on the way up driving on Route 7, I saw Lake Champlain and the mountains. I figured this would be a place I’d like to spend the rest of my life. So far I have.

George: I recall at that time GE had just taken over the plant from Bell. What did you do there?

Lew: I started in test equipment design, then engineering had problems with certain guns and they wanted somebody to run some tests. One of the problems was the 20mm Hispano Suiza in the turret; it was the electric primed M24. Anyway, that gun would misfire if it got dirty, and particularly at high altitude. Nobody could figure out why. So, I got them to send some guns in after test firing and before cleaning and put them in the environmental chamber. I quickly found out where the electric circuits were shorting out. Just about the time I figured out how to fix it, they stopped using the gun. Years later, after I retired, one of my engineer buddies at GE called me and said the Portuguese Air Force was having misfire problems with their M24’s. We put together a proposal to go to Portugal to investigate the problem. “You pay our way, for us and our wives, and I can solve your problem.” They didn’t go for it and it kind of ticked me off because I figured I was probably the only guy in the world who could solve that problem in a hurry and that would have saved them a lot of time and money. (Lew proceeds to describe the problem and the way he fixed it. He jokingly voices some concern about how he is now releasing details of the fix).

George: That’s OK, Lew. When I write this interview up, I’m going to say that the problem was easily solved by: dot, dot, dot. (laughter-Too bad for you, Portugal!)

Lew: I could have solved it in five minutes. Anyway, that was one of my jobs on the test program. We had taken over the turret business from Bell aircraft. After the turrets were assembled, I had to sell them to the USAF, and I had an Air Force inspector who watched as I put the turret through its drills.

George: Which aircraft would that have been?

Lew: These were for the B29, and B47. The gun was the 20mm Hispano Suiza single barrel cannon. This was before Gatling guns. I managed to wrangle two assignments in Burlington, but still had to do a fourth, so I went down to Lynn, Mass and worked on steam turbines for a few months. Then it was back to Burlington for about a year. Then I got drafted. The armament business was slowing down so the Pentagon decided they would stop sending out deferments and start drafting the engineers that had them. The Army was smart though, they still needed engineers, so they set up the science and professional program in the Army. Instead of putting us in infantry they put us in jobs where we could do engineering.

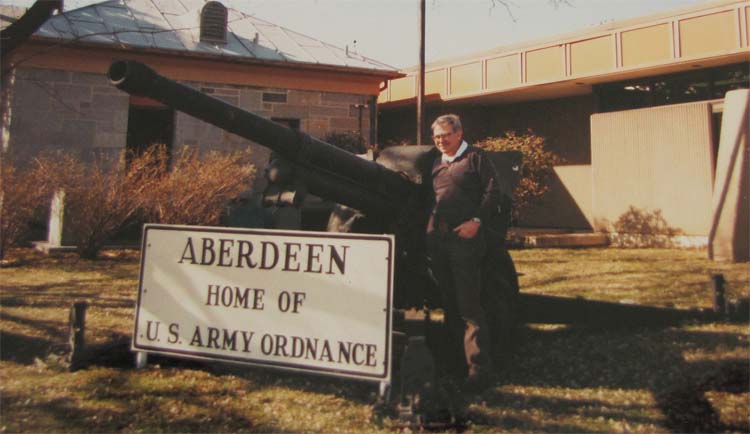

I was sent to Aberdeen Proving Grounds. Two years at Aberdeen as project engineer on the new 110mm howitzer. If you go to downtown Aberdeen, Maryland, in front of the police station is a prototype of the howitzer. The Germans were developing a new artillery piece. The Allies found a prototype in Poland after the war and sent it over to Aberdeen so they could look it over and test it. They decided it was a neat one. I was the project engineer for testing – “Proof Director,” as they called it. I worked on it almost exclusively for the whole two years I was there. It was a nice size – very compact. It had a range of nine miles.

George: Did the howitzer go into production?

Lew: No, Too bad too, because it was a very neat design. It had four trails, so it could fire in 360 degree positions. It had variable recoil. As you elevated the gun the recoil adapter would diminish so it didn’t have to be staked down. I had a gun crew trained to fire 40 seconds after the vehicle stopped. It would also lift the wheels off the ground automatically.

One day on the test range, we were test firing at maximum elevation. I got clearance to fire and they said, “There’s a lot of wind, but we’ll try to track it.” After the first round I got the command, “Hold your fire – that one landed on the eastern shore!” Another time we were putting on a demo at Aberdeen and we had all these weapons lined up to take turns firing. After this one guy fired a bazooka, he laid it on the ground next to us. The next system up was my 110mm howitzer with a muzzle brake on it. The blast from that muzzle brake shattered the bazooka into a million pieces.

We had a 155mm we were developing too. These were both cancelled in 1955 or ‘56. I have a picture of myself in front of the gun. Years after that, one of the GE engineering technicians, Ski Beckwith, and I were in Aberdeen driving down the main drag when I spotted it. I said, “Ski, pull over, I need to take a picture.”

George: Sounds like the Aberdeen experience wasn’t bad at all, why didn’t you stay there?

Lew: They did make me an offer. At the time I was a buck private and I had a second lieutenant working for me. I had become the right hand man of the branch chief. He introduced me to the lieutenant and told the guy, “This is private Wetzel. You work for him. Do whatever he says.” (laughter)

After they offered me a permanent job, they said “We’ll have to put you on a different project until your security clearance comes through.” I said: “What? I already have a security clearance.” “Yeah, but that’s all gone when you leave the service.” I thought to myself: “Do I want to put up with this kind of bullshit?”

It would have been an interesting job, but I was living in the South, in a trailer with no air conditioning. I thought, if I had a civilian job, I could afford air conditioning. Then I decided to go back up to Burlington. I interviewed other places too, though. Raytheon was one. They had a crazy project they were working on to cook food with microwaves! Can you imagine that? They were looking for engineers to develop what they called a “Radar Range.” I could have gotten in on the ground floor. I went to TRW too. Their office was in downtown Cleveland and they said they’d be moving to Port Clinton, but didn’t say when. Did I want to commute down there every day? So I turned it down and went back to GE Burlington.

It was very shortly after that they got the first production contract for the Gatling gun. Up to that time, the engineers and all of the development work had been done in GE-Schenectady. I spent a few days down there and a few days back in Burlington basically moving the whole project. Not all of the engineers moved up, so I took over responsibility for the engineering work of people who stayed back.

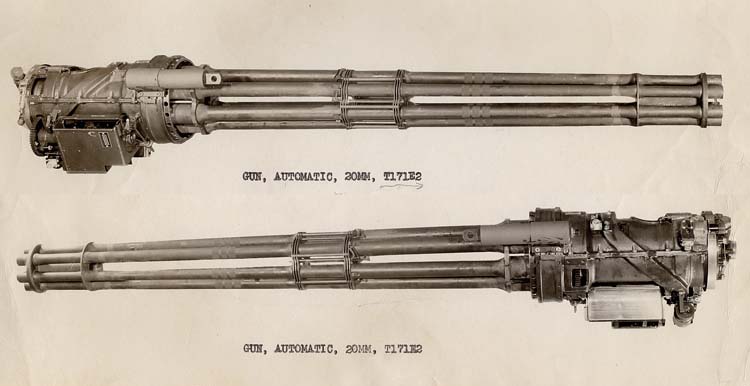

George: How far along was the development of the M61 when it moved up from Schenectady?

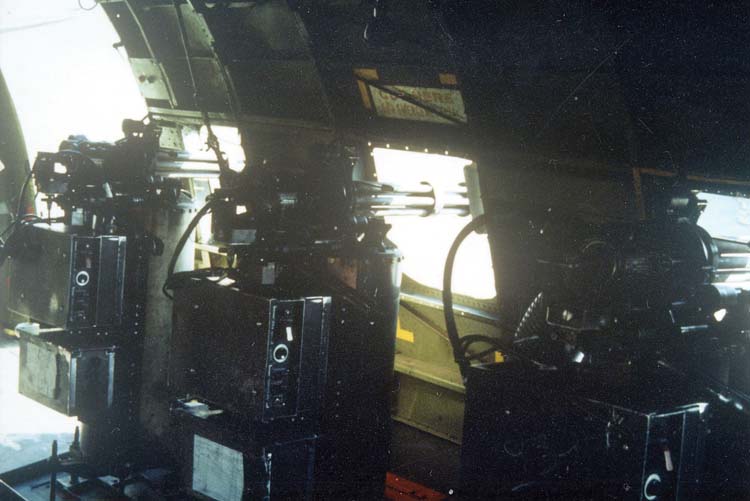

Lew: You know, it was just barely working. They had prototypes but they had a crash at least once a week. We had a production contract for a gun that still wasn’t working. The biggest problem was the feed system. You know the major problems are always there; trying to feed a high rate of fire gun. We really tore into it and tried to figure out what was going wrong while at the same time production people were trying to figure out how to build it. I was responsible for all the feed systems and for the clearing methods for the Vulcan. We used a hold back clearing for the first guns while other guns used diversion clearing or declutching feeders. A cookoff in one of these guns could be disastrous, so they had to be clear at the end of every burst.

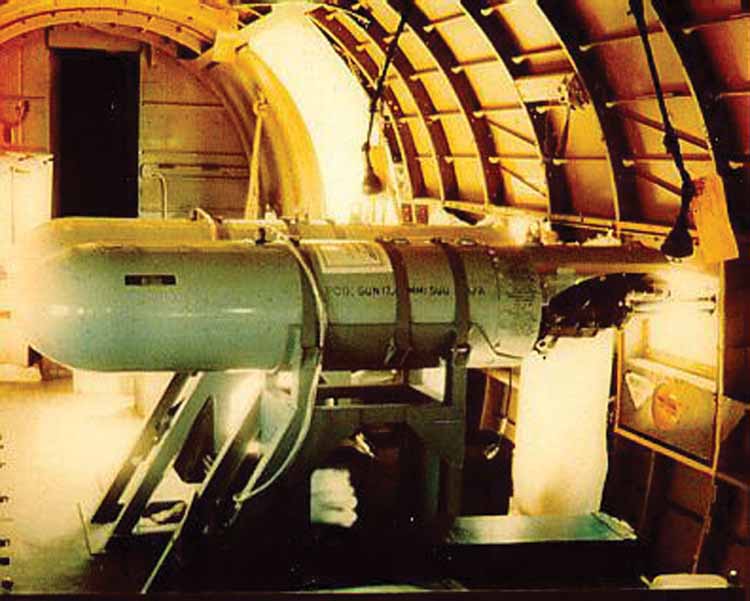

It wasn’t up to the 6,000 shot per minute rate we use today. The linked ammunition caused us to hold the firing rate to 4,000 shots per minute. The F104 aircraft was the first aircraft to use the M61.

George: It takes a lot of power to move all the ammo at full speed.

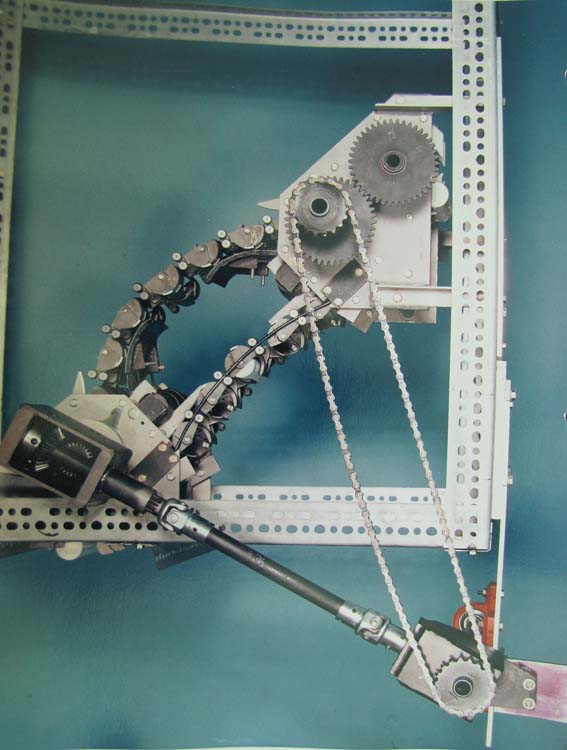

Lew: It’s not just the power; it’s the wear and tear on the parts too. The F104 was the first application and the F105 was coming along. The Roy Sanford company had developed the double lead, helical auger, linkless feed concept and they had a prototype which they could make work – once. They had only one technician, who would tinker the system for a week and only then could they get one burst off. Sanford had convinced the Air Force that the prototype was working, but we had the production contract and we spent a lot of time tearing into it. Here again, we were trying to design the production system and at the same time trying to get the prototype to work.

We did a combination of debugging and production design and built another prototype and it worked out very well. That was the very first linkless feed system for the electric powered Gatling. It did work. This was the first Gatling aircraft system used in Vietnam.

After the Vulcan was in production I went right into the design of the feed system for the M75 40mm grenade launcher. It was a Ford externally powered gun that went into a turret on the front end of a Huey helicopter. It was classified at the time. There was never any publicity on it. I talked to some pilots from Vietnam who told me it was super for hitting sampans. That 40mm grenade is wicked. The guys used it and loved it. I developed the turret too. After we got it into production, I got to fly all over the range at Underhill making helicopter strafing runs. Our favorite target was the abandoned Doyle farm down range. We’d shoot into the roof. That was a lot of fun.

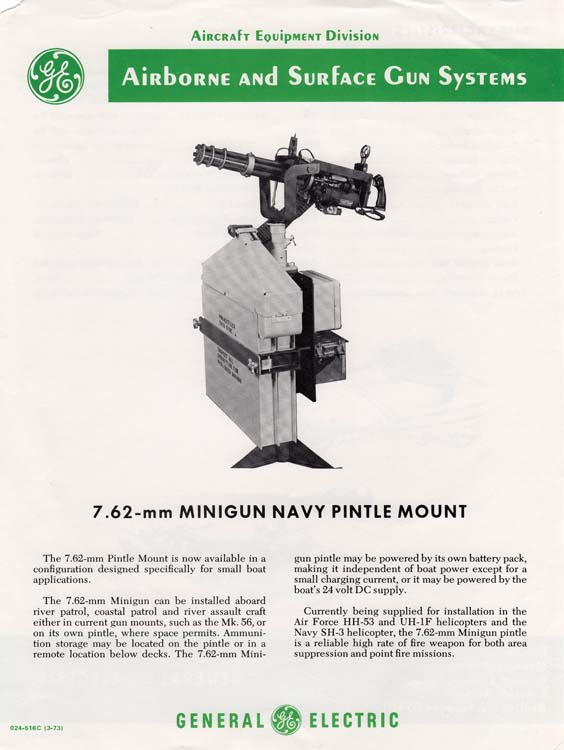

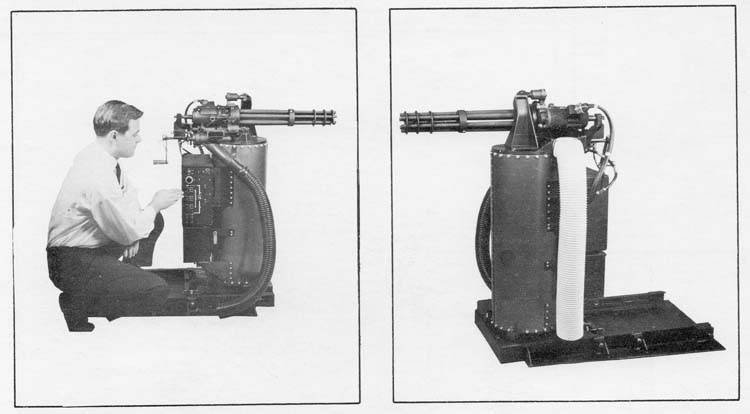

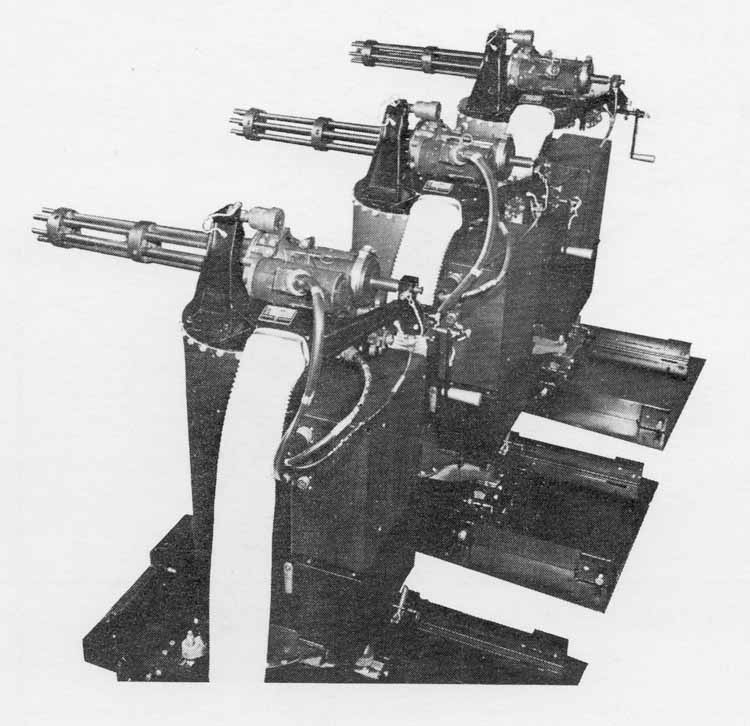

My next project after they designed the 7.62mm Minigun was the Minipod….

George: Hold it, Lew! Tell us who designed the Minigun?

Lew: It was Ray Patenaude, but you know, in the beginning we had two Miniguns. One was designed by Bob Chiabrandy and the other was Patenaude’s. Chiabrandy’s worked all the time and Patenaudes’ only some of the time. There was no question Chiabrandy’s was superior.

But for some reason…. Well, you know Ray intimidated the hell out of people. So anyway, after developing the gun, I got to design the Minipod. We built prototypes. My position was to develop the feed system. I was almost always working on feed systems. I was lead engineer and I had Bert Clark and Bob Kirkpatrick working for me as a designers.

George: Tell me Lew, who came up with the ammunition handoff between the feed drum and the Minigun?

Lew: I can’t remember who it was right now, but I do want to say that it was one of the neat things about the GE system. The engineer and the designer worked together. Nowadays, the engineer works alone on a design project. I think you lose a lot because we used to have two guys tossing ideas back and forth.

George: It’s a mini brainstorming session.

Lew: It really is. I think the GE system was just so super. Bert Clark and I butted heads all the time. I was forever telling Bert: “If you think that will work, then draw it up and we’ll build it.” He was on notice and the pressure was on to get it done. Most of the time he came through. You know, Bert had worked for Werner von Braun on the space program when he was in Huntsville, Alabama. He was really sharp.

George: So we’re at Minipod – you were doing feed systems…

Lew: It was during Vietnam and we had to get that thing going really fast. The stupid thing was that the Minipod and the Minigun were on separate contracts. After we finished acceptance testing the pod, we’d check everything over, take the gun out, and pack up the pod less the gun. The gun went into another box. Each went on its own way, shipped on its own contract. One day we got a call from Vietnam: “We have a bunch of pods but no guns.” And another base called and said they had guns but no pods. We sent George McGarry over there. Do you remember him?

George: Yeah, George was a Marine who worked for Col. George Chinn studying the guns and helping him write the first four volumes of The Machine Gun. He came to GE after he retired from the Corps.

Lew: Well, McGarry commandeered a C47 and got the two back together. George knew how to get people to do things. He put the pods back together. Unfortunately some of the pods got shipped upside down. They had NiCad batteries with phosphoric acid which leaked out and he had to repair a lot of things. Eventually he got them working and on the aircraft. I don’t think it could have happened without McGarry. You know, someone with his experience.

That was right after we tried to side fire. You’re aware of how Puff the Magic Dragon came about?

George: Not exactly

Lew: There was an Army Captain at Wright field – his last name was Terry – I can’t remember his first name. CPT Terry came up with the idea to side fire out of an airplane flying a pylon turn around a target. His thinking was that that was a good way to bring a lot of firepower on a target. At the time, the Vietnamese were having a problem in their walled cities, with the Viet Cong getting on ladders and invading them. These cities were being attacked at night, and CPT Terry believed the side firing technique would work.

Terry asked if we would help mount some Minipods on a C47. We gave them a technician and tried it at Hurlbut Field and at Eglin: it looked pretty promising. They tried 20mm Vulcan pods too, but the Vulcan pod was overkill. For anti-personnel the Minigun was fine. After using it for a while, they decided to make a pedestal mount (Minigun Module) just for that purpose; which they did. That helped in the Vietnam War. When CPT Terry came up with the idea, General Lemay was Chief of Staff and said “That’s the dumbest idea I ever heard.” But CPT Terry was so convinced; he risked his career on the decision to go ahead with it. It’s the kind of thing that it takes some times to move the technology forward – to try things you are convinced will work. Luckily, it really did.

George: Did you work on the Minigun module?

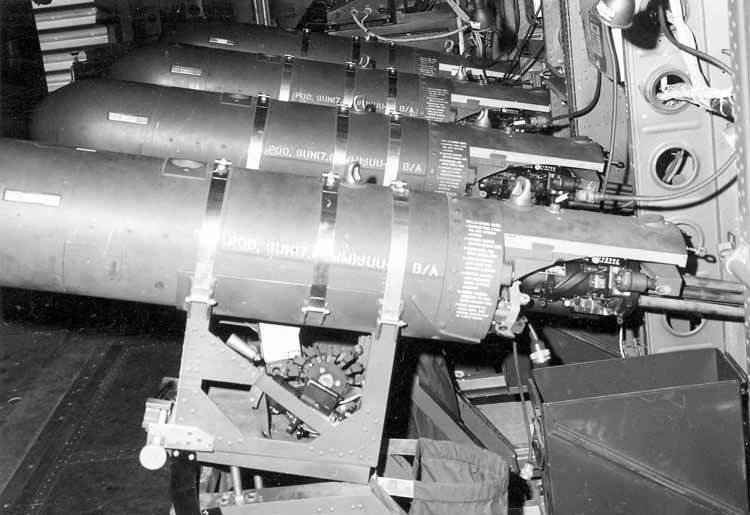

Lew: I did the concept for the module. I basically developed the whole feed system for it. It was a helical feed drum, like a Minipod but turned on end. I developed the whole thing, and then we were starting on the 25mm caseless Gatling cannon and they put Jay Trumper in charge of the Minigun module. The module was designed with the gun at a right angle to the linkless ammunition feed system. It was designed with simplified controls so an operator could reload it easily at night. As soon as they went into production the Module quickly replaced the Minipod on the C47 Dragon ships.

George: So, after you left the Minigun Module project you started working on the 25mm Caseless cannon that was designed to be used in the F15?

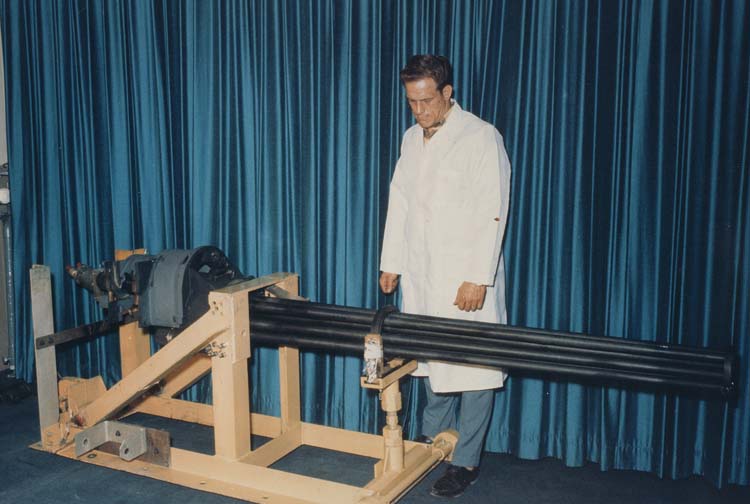

Lew: That’s right. We set up a separate unit that I headed up.

There were two 25mm caseless guns in competition. Ford Aerospace and GE had parallel contracts, and each of us used different ammo contractors. We farmed out the ammo to Hercules and had a shoot off. We both had problems. You know that ammo is uncased and it can just go up in flames. They had a special water deluge system to douse the fires. I know both GE and Ford had fires. We might have had one more than Ford, but in the end, the Air Force decided Ford was the winner.

During final negotiations, the Air Force decided the contractors should respond with a Firm Fixed Price contract with guaranteed performance. You know, this is kind of dumb for a high risk program. Not only was it risky, but they tried to get me to agree to their technical requirements too. I said, “These requirements are mutually exclusive. We can’t meet the recoil requirements and at the same time use the energy to drive the gun. You have to back up the recoil with something!” In the end, I priced it accordingly and Ford won. Ford ended up investing about $20 million of their own money and finally the program was cancelled. You know that’s really sad because it is a good idea.

George: We’re still trying to get into case telescoped and caseless. AAI’s new machine gun works just like our old 25mm case telescoped gun.

Lew: Well of course, how else are you going to do it? You know the real problem was that if you have a misfire you have to eject it. It might just be a hangfire and that gets really hairy. They had some interesting concepts on coating the round – like using intubescent paint as a fire retardant. This gun system was going to be the primary armament of the F15. The whole system could be jettisoned so in case you had a fire you’d push a button and the whole thing would eject. It was part of the original design.

The interview with Lew Wetzel continues with a look at the only medium caliber cannon to be designed for “no-tools” assembly/disassembly. Lew explains how to take one of these cannons along with you for a briefing in the Pentagon. After some design work on single barrel cannons, Lew explains how and why he designed the 30mm GPU 5/A as a companion weapon system to the gun system on the A-10. These and other interesting tales that offer a unique insight into his unique design ability where he makes extensive use of modeling to prove out the most challenging parts of his designs, reducing risk, saving time and minimizing costs.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V16N1 (March 2012) |