By Robert Bruce

“In Vietnam around the end of 1965, US forces first engaged disciplined, regular troops of the North Vietnamese Army in the bloody battles of Ia Drang. The enemy’s ‘arm of choice’ was the AK47. General Wheeler’s ‘worldwide’ trials had shown the AK to be ‘clearly inferior’ to US weapons, and most US soldiers at that time had shown a preference for the M14 over the then-AR-15. But that was 1962 and peacetime, and this was 1965 and counting. America was at war in the jungle, again.” From The Black Rifle.

It should surprise no one who is in any way attuned to the complex relationships of men and their machines that heated controversy remains even today between proponents of the M14 and those of the M16. Both rifles, and the very different cartridges they fire, have admirable characteristics and unfortunate flaws. Both were well suited for the terrain, conditions, tactics and troops they were originally intended for. Neither was the perfect rifle, but which was “Numba One” in Vietnam?

The M14

During the “Cold War” which followed the stalemate in Korea, America stepped up its search for a suitably modernized shoulder weapon to replace the venerable but obsolescent M1. Ideally, the resulting rifle was supposed to be agreed upon and adopted by all sixteen nations forming the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) that sought to prevent the Soviet Union and its allies from further spreading Godless Communism.

For all sorts of reasons that have filled innumerable books and fascinated students of military history and armament, that didn’t happen. A dozen years after the end of WWII, during which most of the rest of NATO had happily chosen the Belgian FAL, America’s soldiers and marines got the home-grown M14, a product of Springfield Armory (the government arsenal, not the current commercial firm). This, after a bait-and-switch trick where our allies had grudgingly adopted the US 7.62 x 51mm T65E3 cartridge, essentially a shortened – thus less powerful – version of the combat classic US .30-06 (7.62 x 63mm) round.

For all intents and purposes, the new M14 was a product-improved M1 rifle characterized by lighter weight, better balance, increased on-board ammunition supply, and selective-fire capability. The rifle also boasted greater controllability and accuracy in semiauto fire than its predecessor; largely due to the reduced recoil of its new cartridge at no significant penalty in range and knockdown power.

Sturdily built using traditional manufacturing methods with machined steel and hardwood, the manly-looking M14 was plenty tough for grenade launching, bayonet fighting and standing up to the routine abuse that soldiers inflict even in peacetime. All in all, it was an effective, serviceable rifle for the kind of warfare that would likely ensue if the Soviet Union and its allies decided to steamroll westward.

Full Auto Follies

Unfortunately, the “Fourteen” was relatively expensive, a bit tricky to manufacture, and had a few problems in the reliability area despite such refinements as a roller cam on the right bolt locking lug and hard-chromed bore. However, this wasn’t nearly as much to be concerned with as the rifle’s near-uncontrollability in full auto fire; arguably the M14’s only significant new feature vs. the old M1. (Magazine capacity notwithstanding).

The Army’s best attempts at curing the problem included addition of a heavy barrel, sturdy folding bipod, sophisticated muzzle brake, and yes, even a nicely sculpted new wooden stock with pistol grips fore and aft. Alas, the resulting M14E2 (later designated M14A1) squad automatic rifle version remained clearly inferior to the BAR, a genuine embarrassment.

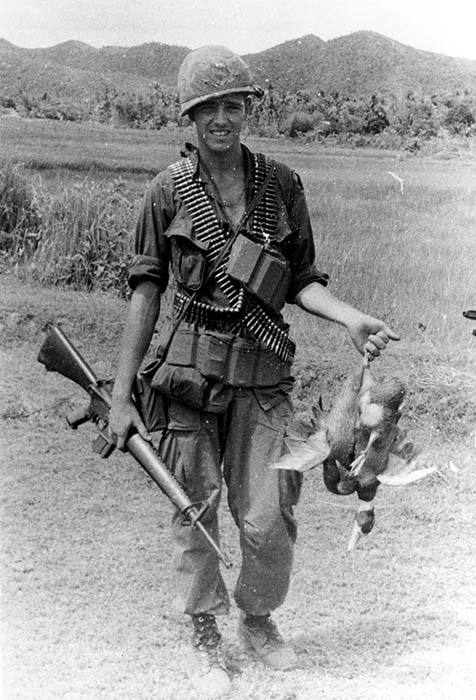

Both the standard M14 and the tricked-up A1 models were in general issue throughout the Army and Marine Corps when the first American ground combat units of both services were sent to Vietnam in 1965. Not to worry, though, as early combat reports rated the hard-hitting, long-ranging Fourteen as acceptably effective and reliable. So far, so good, but it wasn’t long before soldiers and marines were ordered to exchange their big .30 caliber rifles for little .22’s.

SALVO, SPIW, ARPA and AR-15

The story is far too big, juicy and convoluted to recount here, but the whole time the Army was struggling to field and then fix the M14, it was spending obscene amounts of money somewhere way out in left field. Projects known by the evocative acronyms SALVO and SPIW, were decades-long experimentation with all sorts of radical, high-tech rifles and ammo with an eye toward significantly improving the combat effectiveness of its Nuclear Age infantrymen. Didn’t work.

What did work – at least well enough at the time – was handed to the Army on a silver platter by the upstart firm of ArmaLite in partnership with time-honored Colt’s Patent Firearms Company. Making a very long story short, an innovative NATO standard caliber rifle, designed by the gifted Eugene Stoner, had been scaled down at Colt to very effectively shoot a high-velocity varmint cartridge that had become wildly popular with sportsmen and hunters. Stamped on the side of the magazine well of receivers on the first limited production run of the new 5.56 x 45 mm rifles was the designation “ARMALITE AR15, Cal. .223, Model 01.”

Tests in Saigon and stateside by the Army’s own Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) in 1961-62, showed the AR-15 to be outstanding in virtually every comparison to existing US shoulder weapons. In particular, “its semi-automatic firing accuracy is comparable to that of the M1 rifle, while its automatic firing accuracy is considered superior to that of the Browning Automatic Rifle.” Strong stuff.

At about this same time the M14 rifle production and fielding program collapsed from a multitude of problems and the Ordnance establishment could no longer hold back the rising tide of support for the AR-15. The Army reluctantly placed an order for some 85,000 Colt rifles, now officially designated M16, with first deliveries scheduled for early 1964. A modified version designated M16E1, featuring a spring plunger to force the bolt closed if needed, quickly followed.

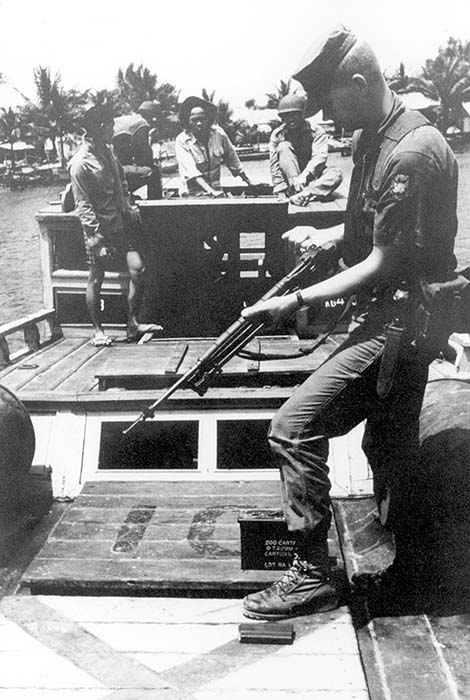

The first units equipped from this and subsequent orders included USAF security police, Army Special Forces and Airborne, Navy Special Operations, and MAAG advisers in Vietnam. Conspicuously absent from this list are the ARVN who had served so conveniently as the reason for considering the AR-15 in the first place.

Dirty Secrets

As fighting in Vietnam heated up in scale and intensity with arrival of more and more American units freshly armed with M16 rifles and mounting aggressive operations against the omnipresent Viet Cong, things began to go terribly wrong. Sporadic reports early on of serious stoppages and gross malfunctions of the M16 rifle began flooding in by the end of ’65. The most common stoppage was failure to extract fired cartridge cases, typically caused by a heavily carbonized and rust-pitted chamber. News reporters picked up the alarm and soon the American public became justifiably outraged over stories of GIs dying face down in the mud because of hopelessly jammed rifles.

Subsequent investigation showed combat failures of the M16E1 were partially the fault of inevitable “bugs” in the design of specific parts, sloppy manufacture, inadequate inspection, hasty fielding without adequate training, and the astonishing lack of specialized cleaning equipment needed for field maintenance! But the single most damning factor in the M16’s sorry combat performance at the time was bad ammo; the result of an unholy alliance of cost-cutting and corner-cutting.

Sadly, not only was the ammo left essentially as it was, but it took many months before sufficient numbers of adequate cleaning tools reached the front line troops. No excuse in the world justifies this outrage that borders on criminal negligence.

Product Improvements

Making the best of a bad situation, Colt’s engineers came up with a number of changes, two of which were most significant; an improved buffer, and hard-chroming the chamber. The first helped to solve problems of parts wear and breakage due to excessive full auto cyclic rate, and the second drastically reduced instances of corroded chambers leading to extraction failures. These modifications, along with regular and thorough cleaning gave newly fielded M16A1’s a quantum leap in reliability and things got decidedly better after 1967.

But, by this time nearly irreparable damage had been done to the reputation of the M16 both among combat troops in Vietnam and the American public. In contrast, the enemy’s AK-47/PRC Type 56 assault rifle had grown in folklore into what many considered the world’s most reliable, accurate and deadly shoulder weapon. Certainly not the most accurate, but that was the reputation it was gaining.

Back from the Dead

On the other hand, for those who properly employed the Sixteen, cleaning it often and lubricating it correctly, the “Black Rifle” proved more than a match for Kalashnikov’s AK. Its 5.56mm 55 grain bullet shot fast and flat, tumbling on entry to cause catastrophic wounds and shock-induced death. Its semiauto accuracy and full auto controllability were decidedly superior to that of the AK. It was nearly 3 lbs. lighter, and considerably more ammo could be carried for the same overall weight.

For many veterans and other RKI’s, there is little doubt that the compact, light, and fast-firing M16 was and is a better weapon for jungle combat than the longer, heavier, and barely controllable in full auto M14. Although its 5.56mm cartridge is certainly not nearly as capable of heavy brush penetration as the big and comparatively slow US 7.62 x 54 mm and the Soviet/VC/NVA 7.62 x 39 mm, it produces far less recoil — a critical factor in full auto accuracy — and its wounding/killing potential is in some ways superior to both rivals.

Standard A

The “experimental” designation was dropped on 26 May 1967 when Colt’s XM16E1 became the “US Rifle, 5.56mm, M16A1,” officially replacing the big M14 as “Standard A” throughout the Army. By the end of 1967 enough rifles had made it to Vietnam to arm all of the Army and Marine Corps’ ground combat units. Finally, by December 1968, 600,000 additional M16’s had been delivered into the hands of our Vietnamese partners.

This soon began to have a noticeable effect on the battlefield. In particular, intelligence analysis after the 1968 Tet Offensive showed the NVA to be particularly shaken by the effective firepower of both US and ARVN units now fully equipped with M16’s. Captured M16’s became coveted items for the VC, who called it the “Black Rifle.” Then, it was no cause for amusement among some US troops who had earlier disparaged the Sixteen as inferior to the enemy AK, to now be on the receiving end of 5.56mm fire.

M14 Rifle Technical Specifications

Caliber: 7.62 x 51 mm NATO Standard (.30 caliber)

Weight: 10.1 lbs. loaded

Overall length: 44.3 in.

Feed: 20 round detachable box magazine

Operation: Gas piston

Cyclic rate: 750 rpm

Muzzle velocity: 2800 fps

Maximum range: 3725 meters

Effective range: 460 meters

M16A1 Rifle Technical Specifications

Caliber: 5.56 x 45mm (.223 caliber)

Weight: 7.6 lbs. loaded

Overall length: 39 in.

Feed: 20 round detachable box magazine

Operation: Direct gas

Cyclic rate: 750 rpm

Muzzle velocity: 3250 fps

Maximum range: 2653 meters

Effective range: 460 meters

Primary Reference Sources

U.S. Rifle M14, Collector Grade Pubs. 1988

The Black Rifle: M16 Retrospective, Collector Grade Pubs., 1987

Personal Firepower (Illustrated History of Vietnam War Series), Bantam Books, 1988

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V5N7 (April 2002) |