By Jean Huon

The author recently made a trip to Vietnam and selected a tour which led to the main battlefields, where the Communists fought the French and later the South Vietnamese and the American troops, and several military museums.

History of the Country

In the past, the Indochinese Peninsula was a meeting point for itinerant people from China and India and South seas mariners. After 1801, the Nguyen Dynasty became the leader of a large state called Vietnam, ranging from the Chinese border to the Ca Mau Peninsula at the southern tip of the country. The border was pushed to the west after annexation of the Cambodia and Laos districts. The Dynasty remained in control of the country until 1945, and the last emperor was Bao Dai.

French Colony

Portuguese and French missionaries settled in Vietnam around the 16th century and established a religious, commercial and strategic organization in Indochina. Protectorates were established with Annam and Tonkin in 1883, confirmed by the Tianjin Treaty in 1858 after a conflict with China. The Indochina Union, including Tonkin, Annam, Cochinchina and Cambodia, was established in 1887; later in 1898, Laos and Kouang Tcheou Wan area (formerly Chinese) joined the Union.

An assembly of representatives for Annam and Tonkin was organized in 1928. An ambitious program permitted installations of infrastructure, industrial development and many other activities. The country was one of the most prosperous in Southeast Asia.

Vietnamese Communists

During the 19th century, mandarins (seigniorial) were the main assailants against the French. After WWI, the opposition was taken up by the bourgeoisie, enriched by the economic growth and by some intellectuals educated in French universities. But the most virulent opponent was a young revolutionary Vietnamese, educated by the Komintern in Moscow and the Red Chinese. His name was Nguyen Ai Quoc, but he took the pseudonym of “Ho Chi Minh” after he created the Vietnamese Communist Party in February 1930. During WWII, he established a structured organization in many places of the country and founded the Front for Independence of Vietnam in 1941.

Japanese Occupation

In August 1940, 30,000 Japanese soldiers invaded Indochina, but the French administration remained in place.

War with Thailand

On September 25, 1940, on the pretense of territorial claims in Laos and Cambodia, Thailand invaded Indochina. After some air raids, a Thai land offensive was launched, during which the French troops resisted with difficulties.

France replied with a naval assault against the Siamese Navy at Koh Chang, where in less than 2 hours, three torpedo boats and two battleships were sunk. Japan, which was part of the conflict, proposed a mediation. It resulted in an increase of its influence in Indochina. France had to give away some districts in the west of the Indochinese confederation. These territories were returned to France only in 1947.

Act of Aggression March 9, 1945

On March 9, 1945, the Japanese tried to destabilize the French administration and its small colonial army and then give its armament to the Vietnamese nationalists. But when Japan surrendered, neither the United States, Great Britain or China wished to see the comeback of France in Indochina.

France Comes Back

France returned with Admiral d’Argenlieu as governor and General Leclerc as chief of the military headquarters. On September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed independence of the country and created the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

Jean Sainteny, a diplomat, was tasked to discuss relations with Ho Chi Minh. They reached an agreement preliminary to a conference meant to resolve the relationship between the French and Vietnamese, but Admiral d’Argenlieu denounced the agreement, and General Leclerc, who disagreed with him, asked to be relieved of his command.

A peace conference was organized in Fontainebleau on September 10, 1946, but it failed. It was the result of the admiral’s stubbornness, the intransigence of French politics and the xenophobia of the Vietnamese.

War in Indochina

General Giap, the commander of the Vietnamese People’s Army, began the First Indochina War in December 1946. Gradually, the entire country became involved. The French troops, 70,000 strong, were systematically attacked. Against guerilla warfare, tanks, aircraft and artillery were powerless. France reinforced the Southeast Asia Expeditionary Force with volunteers, but the troops were poorly equipped with old vehicles and obsolete equipment or armament.

The French Army was constrained to defensive action. In December 1950, General de Lattre de Tassigny was appointed chief commander. He tried to improve the situation, but his poor health did not permit him to succeed. He won an increase of the American supply effort and the creation of a Vietnamese Army. His successor, General Salan, followed a similar strategy. But back in France, the war was unpopular, the government was unsteady, and trade unions close to the Communist Party provoked sabotage and betrayed their country.

Dien Bien Phu

The French headquarters tried to remove resistance in the North by installing a large military base from where operation against the Viet Minh could be organized to prevent infiltrations into Tonkin. During the build-up of the French installation in the Dien Bien Phu basin, the Viet Minh built bunkers hollowed out of the limestone cliffs overhanging the base. More than 260,000 coolies were commandeered to ferry equipment, big bore guns and ammunition with their bicycles.

The offensive began on March 13, 1954, with an artillery bombardment followed by attacks of the strongholds built by the French on the hills bearing Christian code names: Anne-Marie, Gabrielle, Beatrice, Huguette, Françoise, Dominque, Claudine, Eliane and Isabelle.

Despite troops being air-dropped for reinforcement, the base surrendered on May 7, 1954. After the battle, 2,293 French soldiers were killed, 5,195 were wounded and 11,721 were taken prisoners. They walked more than 400 miles to reach internment camps where their “political reeducation” was organized. Only 3,290 returned to France.

Victory of the Viet Minh; the men have Berthier M1902 rifles.

Geneva Conference

After the disaster in Dien Bien Phu, the French government disengaged quickly. The Geneva Accords in July 1954 stopped the war. Laos and Cambodia became independent. Tonkin, Annam and Cochinchina were separated in two states: The Democratic Republic of Vietnam, north of the 17th parallel, and the Republic of Vietnam to the south. The French Army left Southeast Asia in 1955.

American Intervention

After the French departure, the U.S. supported the South Vietnamese government. In May 1959, 15 task forces, 46 air bases and 11 Navy bases were set up with 685 military advisors. After President Johnson arrived at the White House, the American expeditionary force increased to 543,482 men on April 30, 1969.

The Communists built up their offensive and systematically attacked American and South Vietnamese troops. In January 1969, peace negotiations were opened in Paris.

President Nixon announced a progressive retreat of the American forces. A peace agreement was reached on January 27, 1973, by Henri Kissinger and Le Duc Tho. On March 29, the last American Combat troops left the country.

Dien Bien Phu French memorial.

The Fall of Saigon

The American pullout did not stop the war. Launched in March 1975, the North Vietnamese People’s Army’s offensive pushed across South Vietnam, and districts fell despite the resistance of the Vietnamese Army. Hue surrendered on March 25 and Da Nang on April 2.

The offensive on Saigon began on April 27 and was achieved 3 days later. The following year, the country was unified and became the Vietnamese Socialist Republic. Thirty years of war considerably upset Southeast Asia and caused 2 million victims.

My Trip to Vietnam

After a first tour, I wished to come back for a better knowledge of the country, discover new landscapes, meet local people and visit historical museums.

The trip began in Hanoi. The city now has a new international airport, highways, bridges and high tower buildings, all generally built by Chinese, Japanese and/or Korean investors. The population is now 7.6 million people with about 3 million bicycles, auto cycles and scooters. We visited several museums: Vietnam Museum of Ethnology, Temple of Literature to learn about Confucius and finally the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum where we saw the guard change.

One day later we went to Dien Bien Phu (DBP). Before boarding, I imagined all the boys who at the same place 60 years ago traveled by other planes and jumped—often for the first time—for a hopeless fight.

After a 1-hour flight we arrived at DBP. The village which existed in 1954 is now a 50,000-person city. It is long and narrow, built next to the airport railway which is the site of the former runway created before the battle. The Eliane 2 entrenchment is faithfully regenerated but with concrete sand bags. Crossing through there is particularly touching, and I take to heart the glory and sacrifice here.

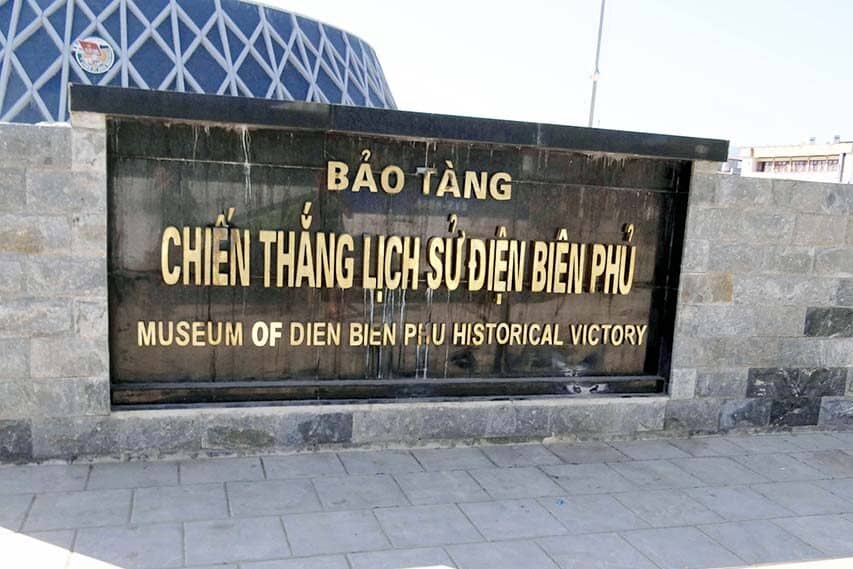

Military Museums

The Dien Bien Phu Museum presents several scenes of the battle, small arms and equipment. Small arms exhibited in the museum are the glint of military material used by the French Army or Viet Minh troops. A wide variety of French and other small arms from WWII include:

- Approximately 10 variations of pistols and revolvers (the MAS 35 S, SACM 35A, P38, Colt M1911, Browning, MAB or other .32 pistol, M1892 revolver, Smith & Wesson, Enfield, Webley and more);

- MAS-38, MAT-49, Thompson, STEN, MP40 submachine guns;

- Berthier rifles, MAS-36 and MAS-36 CR39, U.S. M1 carbine, Garand M1, U.S. Enfield M1917, Mauser K98k and Lee–Enfield;

- M1924/M29, Bren, BAR, MG34 and MG42 light machine guns; and

- MAC 31, Hotchkiss, Browning M1919A4 or A6, Vickers, M2HB machine guns.

Viet Minh had approximately the same small arms, with a large quantity of M1902 “Indochinese” rifles and also Mosin-Nagants, a Chinese copy of the PPSh 41, ZB vz. 26 and various Russian machine guns, including the DShK-1938/46.

Beyond the military hospital is a necropolis where several thousand soldiers from France and former colonies are buried. This cemetery and the monument were not established by the French government, but by a lone man, Rolf Rodel, a French Foreign Legion veteran.

One day after this visit, we left on a bus headed to the North. We visited several villages and schools where Thaï and Red H’Mong people live and learn the Vietnamese language and the history and culture of living in a communist country.

Then we traveled again by a mountain road. The Black H’Mong (Meos) people who came from China in the 18th century and never joined the Vietnamese live here. Many of them joined the French and are Catholic. Some Meos resistance organizations against Communism remained after 1954. After the departure of the French, they helped the Americans, so Vietnamese do not like them very much. They lived in isolation and were particularly hermetic to Marxist culture. The Vietnamese government consolidated them in villages near roads for easier control.

After traveling through several other towns, including Sapa, Lai Chau and Lao Cai, we returned to Hanoi where there are several military museums, such as:

- B52 Victory Museum, with a lot of information about Hanoi’s anti-aircraft defense. Outside, there are various rockets, anti-aircraft cannons and a MiG-21.

- Vietnam Military History Museum, near the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum, covers approximately 130,000 square feet and testimonies of their fight against the French, Americans and their allies, with many pictures and documents.

On the way back to Hanoi, we visited the small city of Dong Trieu. Between 1885 and 1889, my grandfather’s uncle served here as a Foreign Legion Lieutenant. He fought “Chinese pirates” (rebels) and was wounded. His received the Legion d’honneur medal for his bravery.

From Hanoi, we flew to Hue, the “Forbidden City,” which is the former emperor’s palace. Just beside it is a military museum where there are many American vehicles, tanks and helicopters exhibited.

Heading west en route to Saigon, we followed the Ho Chi Minh Trail and crossed through the small cities of Tan An, Kham Duc, Dak Glei, Dak Sut, Plei Can, Dak To and Dak Ha and on through Dalat. In the past, it was a resort city with many old houses and monuments, miraculously saved from American bombing. We visited the summer residence of Bao Dai, the last Vietnam emperor.

War Remnants Museum in Saigon (now known as Ho Chi Minh City).

Ho Chi Minh City/Saigon

Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) is very crowded with 7 million bicycles or scooters; what will happen when they can buy cars? Our visit included a stop at the War Remnants Museum, which describes the history of the country from 1945, with a large place for the atrocities of the French or American imperialists and south puppet allies! The museum also shows the devastating results of the use of napalm or Agent Orange. But there was nothing about the reeducation camps, inhuman incarceration conditions of the French prisoners after Dien Bien Phu or captured American pilots. The museum has an interesting collection of small arms and on the outside, various materials with wheels, tracks or propellers. There is also a shop with interesting English-language books on the war and nearby an authentic guillotine!

We also toured the Reunification/Independence Palace. Originally built in the late 1870s, the imperial palace was destroyed by an assassination attempt via a bombing in February 1962. At the same site, a presidential palace was built. It was both the residence of the president and the government office. After the fall of Saigon in 1975, it became a museum but sometimes official meetings are organized there. The museum covers the main events of the Republic of Vietnam and capture of the palace by North Vietnamese forces.

The museum and palace permitted us to see firearms and material used by the Viet Cong, South Vietnamese and American forces, which are different from those used during the Indochina War.

At the beginning of the War, Americans used the M2 carbine, Garand, M14, Thompson, Browning M1919A4 and later the M16A1, M79, M60 and a wide variety of mortars or anti-tank guns. Various armored vehicles and tanks such as M50 Ontos with six 106mm guns; helicopters used were the CH-47 Chinook, Bell UH-1 Iroquois and many others. The North Vietnamese used the Russian AK-47 or Chinese Type 56 rifles, machine guns or tanks.

End of the Tour

Our trip concluded with a walk on the historic Catinat Street, now Dong Khoi (“Total Revolution Street”), in Ho Chi Minh City. It is now a very luxurious area with nice hotels, restaurants and stores. The tour finished with a cruise on the Mekong River and a flight back to Paris after a fantastic 16-day trip in Vietnam. I highly recommend visiting Vietnam for all of its military history.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V24N5 (May 2020) |