By Frank Iannamico

Above: An early Patchett machine carbine, with its stock in a folded position. The first Patchetts were designed during World War II.

Classic Submachine Guns, Carbines and Pistols Refined

The Patchett Submachine Gun

The Sten machine carbine (the term “submachine gun” was not used by the British until 1954) was hurriedly conceived during the early stages of World War II, as Great Britain, seriously short of weapons for defense, was facing an invasion by the German Army. The Sten was a rather crude, but reliable and deadly weapon. After the threat of invasion subsided, work began on developing a more refined submachine gun.

George Patchett was an experienced gun designer who went to work for the Sterling Armament Company during World War II. Mr. Patchett designed a fair number of prototype weapons based on his ideas. By 1943, George Patchett’s submachine gun was developed enough to be tested by the military. Designated as the Patchett Mark I machine carbine, the weapon used a number of parts from the Lanchester machine carbine. The Mark I’s magazine housing was attached at a 90-degree angle to the receiver and fed from Sten or Lanchester magazines. After testing, the Patchett Mark I was considered suitable for service, but with plenty of Sten Mk II and Mk IV submachine guns still in service, there were no large orders for the Patchett forthcoming. Undeterred, development of the Patchett continued with the introduction of the Mk II model in 1946. One of the primary features of the Mark II was its magazine housing oriented at an 82-degree forward angle, to accept Patchett’s new double-feed, curved magazine—a vast improvement over the Sten magazine. Finally, during 1953, the Patchett Mark II was adopted as the Gun, Sub-machine, 9mm L2A1. During 1955, the Mark III model was introduced. The Patchett name was dropped and replaced with the name Sterling. The official designation was the Sterling Submachine Gun Mk III, L2A2. The Sterling company continued further development of the weapon resulting in a final version designated as the Sterling Mk IV L2A3.

The Sterling Mark IV L2A3 submachine gun was produced in Great Britain by Sterling and the Royal Ordnance Factory at Fazakerly. Submachine guns produced at Sterling had serial number prefixes using the letters “KR,” “S” and “US.” Fazakerley weapons used the prefix “UF.” Production began during 1955-1956 and ceased at Fazakerly in 1959, Sterling in 1988. The Sterling Mark IV L2A3 remained in British service until 1994.

Sterlings destined for British military service had a Sunkorite 259 satin black painted finish. Commercial Sterlings had the black crinkle finish. The British use of the term “commercial” is a bit misleading. Sales to Commonwealth and governments, other than the British military, were considered “commercial” sales. The Sterling was also licensed for manufacture in Canada as the C1 submachine gun and India as the SAF Machine Carbine A1.

For the police market, Sterling introduced a semi-automatic-only version of the Mk IV L2A3 submachine gun called the “Police Carbine.” The Police Carbine was also available to civilians in countries such as South Africa. Sterling ads boasted, “The Sterling submachine gun has been modified for use by police and civilians in troubled parts of the world,” and the “Perfect weapon of self-defense for those obliged to take such precautions.” The Police Carbine operated the same as the submachine gun, firing from an open bolt. The semi-automatic-only function was made possible by adding a block to the selector lever, preventing it from being rotated to the A (automatic) position. It was soon discovered that the Police Carbine could easily be converted to select-fire by removal of the block or installing a submachine gun selector lever. Police Carbines can easily be identified by their serial numbers that began with a letter “P.”

The U.S. Market

During the 1980s, a new breed of firearm was introduced to the U.S. civilian market; copies of military submachine guns and rifles. The big difference was the clones were semi-automatic-only and had to adhere to strict provisions set by the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms to make them difficult to convert to full-automatic.

Rifle Caliber

Popular U.S. offerings for the market were Colt’s AR-15 rifle, a civilian version of the U.S. military M16, and the Springfield Armory, Inc. M1A copy of the M14. However, both the aforementioned rifles were available before the 1980s. The M1A rifles went into production in 1971; the Colt AR-15 in 1964. Both became popular when many enthusiasts discovered them in the monthly periodicals of the day, followed by special editions of 1980s magazines focusing entirely on the new breed of semi-automatic firearms and the quickly growing accessory market that soon followed.

Many of the semi-automatic firearms were imported. Companies like Heckler and Koch (HK) offered copies of their .223 caliber HK33 as the HK93 and the .308 G3 as the .308 HK91. Other popular firearms were FN’s Belgian-made SAR (FN FAL), China’s AKS rifles and Austria’s Steyr AUGs. Some of the imports were quite expensive, a few costing twice as much as a Colt AR-15.

Pistol Caliber

U.S.-manufactured pistol caliber semi-automatics included the West Hurley Auto-Ordnance M1927A1 Thompsons, MAC-10s, SWD’s M11/Nine, Nighthawk carbine and Wilkinson Arms Linda pistol and Terry carbines.

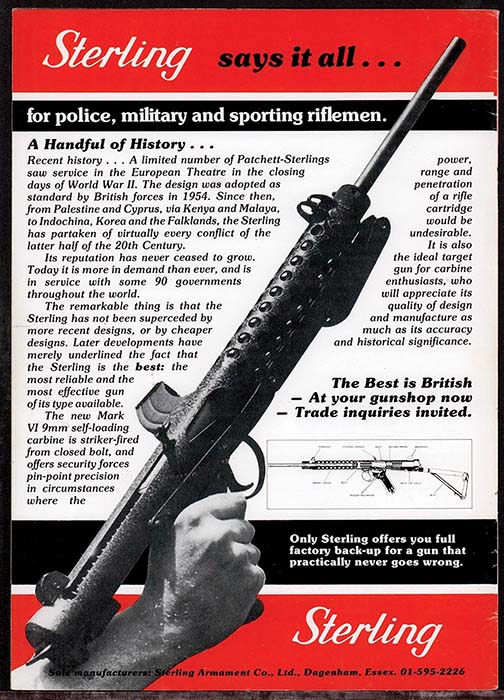

Foreign submachine gun copies included the Heckler and Koch MP5 designated in semi-automatic-only guise as the HK94; Action Arms imported semi-automatic models of the famous UZI submachine gun. Some of the lesser known imports of the 1980s were the British Sterling Mark 6 carbine and Mark 7 pistol, semi-automatic copies of the British Mk IV L2A3 submachine gun.

As per the ATF requirements after 1982, the semi-automatics had to operate from a closed-bolt position.

The introduction of the semi-automatic clones occurred prior to May 19, 1986. This allowed the legal registration and conversion of the firearms into machine guns. After May 19, 1986, the laws were changed making full-auto conversions illegal except for what would be known as restricted post-May dealer samples. Many AR-15s, UZIs, AKs and HK94 carbines were converted prior to the cut-off date. One select-fire conversion that was seldom seen was the desirable British Sterling Mk IV L2A3.

Sterling Mark 6 Carbines

The British-made Sterling Mark 6 carbines were imported by Parker Arms and Armscorp of America. However, the majority of the carbines were imported by Lanchester USA of Dallas, Texas. The suggested retail price of a Sterling Mark 6 was nearly double that of the popular UZI carbine in 1983. Due to their high price, limited advertising and availability, only a small number of the Mark 6 carbines were sold in the U.S.

Selector markings on an Mk 6 semi-automatic carbine imported by Lanchester USA.

Markings on the magazine housing of the semi-automatic Mk 6 carbine.

The primary differences between the Sterling Mark 6 carbine and the Mark IV L2A3 submachine gun were the carbine’s 16-inch barrel and its closed-bolt operation. The receiver itself was similar to its submachine gun counterpart. The overall length of the Mark 6 Sterling is 35-inches with the stock extended and 27-inches with the stock folded. The carbine uses the same 34-round magazines as the submachine gun.

Sterling Mark 7 Pistol

The Sterling Mark 7 was a pistol variation of the Mark 6 carbine without a buttstock. The Mark 7 featured a 4-inch barrel extending through an 8-inch long barrel shroud. The pistol came with a 10-round magazine.

An import ban enacted in 1989 ended most of the importation of foreign semi-automatic rifles and carbines.

Police Automatic Weapons Services (PAWS)

Oregon Class II manufacturer, Bob Imel, had an interest in the British Sterling Mk IV L2A3 submachine gun design. To produce a U.S.-made copy of the Sterling, he formed the Police Automatic Weapons Service better known by the initials “PAWS.” During the 1970s Imel began to manufacture parts and receivers many years before the original surplus British Sterling part sets became available. The results of his efforts were the PAWS ZX-5 submachine gun in 9mm and the ZX-7 in .45ACP. The PAWS guns were only slightly different cosmetically than the Sterling Mk IV L2A3 submachine guns. The 9mm ZX-5 was designed to accept unmodified Sten magazines, in place of original Sterling magazines, due to cost and limited availability at the time. Because of the magazine-well configuration that was oriented 90-degrees to the receiver, the PAWS ZX-5 cannot accept original Sterling curved magazines. The .45 caliber ZX-7 model uses modified M-3 Grease Gun magazines. There were only a few hundred transferable ZX submachine guns made and registered, in .45 and 9mm, before production ceased with the enactment of the May 1986 McClure-Volkmer Amendments to the Gun Control Act, banning the manufacture and registration of transferable machine guns.

After the 1986 ban, Mr. Imel decided to create a semi-automatic carbine version of the PAWS submachine gun, in both 9mm, the ZX 6 and .45 ACP the ZX 8, with the parts left over from his machine gun production line. At that time the market for semi-auto submachine gun clones was flourishing. He started with an ATF-approved receiver design that was similar to and built to the same standards as his submachine guns but that used a closed-bolt design. The carbines came fitted with a 16.5-inch barrel and an UZI-type barrel nut. The blow back carbines weighed 7.5-pounds unloaded and were approximately 35-inches long with the stock in an extended position.

Prior to the 1986 machine gun ban, a number of submachine guns were constructed from part sets. Although the receivers could not be imported, it was legal (AFTER ATF approval) to assemble and register a machine gun with a new U.S.-made receiver. Many World War II submachine gun receivers were made of tubing for ease of wartime manufacturing. One of the most popular was the British Sten Mk II, primarily due to a large number of inexpensive parts. Another popular “tube gun” was the German MP40. Made in smaller numbers were the subguns like the Swedish K due to a limited number of spare part sets.

Submachine gun part sets from the Mk IV L2A3 Sterling were conspicuously absent only because the weapon was still in service with the British and many other countries. Although there were a very small number of original Sterlings in the U.S., most were dealer samples. The desirable Sterling submachine gun was seldom encountered in collections or on the firing line. It wasn’t until around 1994 that Sterling part sets began to be imported. However, eight years after the machine gun ban, there were relatively few registered receiver tubes available that had not been assembled into guns.

Stan Andrewski, a Class II manufacturer from New Hampshire, discovered that Sten Mk II receiver tubes shared many of the same dimensions as the Sterling Mk IV L2A3 submachine gun, except for the position and width of the cocking handle slot. The Sten’s slot is located at 50 degrees on its receiver, while the Sterling’s slot is located at a 60-degree position and is narrower than the Sten’s. Mr. Andrewski believed that the Sten-to-Sterling conversion had merit and sought permission from the Firearms Technology Branch of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms for the conversion. Although ATF eventually granted permission for the Sten-to-Sterling conversion, narrowing of the cocking handle slot was not permitted. This hurdle was overcome by modifying the cocking handle, so the interior portion engages the bolt while the exterior handle travels in the 10-degree offset slot. This is achieved by cutting off the handle section itself and then MIG welding it back at a slightly lower position. The cocking handle has flange added to it, so it fits properly in the wider slot and retains the bolt at the correct angle. The cocking handle and cocking handle block are modified by drilling a hole in each, so the plunger protrudes through them to secure the cocking handle. This makes it a little harder to remove the cocking handle because the plunger must be depressed with a small diameter pin punch, while at the same time pulling outward on the cocking handle sometimes requiring a third hand to accomplish. Due to Mr. Andrewski’s efforts, a number of transferable Sten guns were reconfigured into Sterling submachine guns. Florida Class II manufacturer Don Quinnell also began performing the conversions. Finally, after many years, a transferable “Sterling” submachine gun was available!

Since the initial conversions were approved in 1997, a small number of virgin pre-1986 registered DLO, and a few Wilson-made receiver tubes have surfaced with a Sterling-spec narrow cocking handle slot, allowing an unaltered cocking handle to be used. This quickly resulted in the Sten-tube conversions with the wider cocking handle slot to be snubbed by some and bestowed with the rather condescending nickname “Stenlings.” However, in reality, both are still just “tube guns,” in turn probably slighted by the handful of fortunate owners of “real” British-made Sterling Mk IV L2A3 submachine guns.

With a large number of Sterling parts kits (less receivers) being imported, it was only a matter of time before someone would begin assembling the parts into a semi-automatic carbine. To comply with U.S. laws, the carbines had to have a barrel with a minimum length of 16 inches. Wise Lite Arms of Boyd, Texas, produced a semi-auto carbine and pistol version of the classic Sterling. The carbines were assembled using a mix of newly made U.S. parts (bolt and barrel) and parts from demilitarized Sterling Mark IV parts kits. The Wise Lite carbines operate from a closed bolt to comply with U.S. laws. The pistol version lacking a butt stock has a 4.5-inch barrel.

There aren’t a lot of original accessories available for Sterlings, other than slings, magazine pouches and bayonets. Spare parts kits can still be found; however, many of the kits were bought by fans of the “Star Wars” films. The weapons carried by the Storm Troopers in the films were Sterlings modified for a futuristic look.

(Dan’s note: most of the original “Star Wars” used Sterlings were deactivated to UK standard and sold on the market in the UK.)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V23N1 (January 2019) |