By Peter Suciu

Today, even when you can find a “toy” machine gun for sale, it is bound to be bright plastic with an orange plug on the end—but that is when you can actually find such items in the few remaining toy stores. There was a time when an aisle at the toy store or department store toy section resembled a scaled down gun shop.

There were kid-sized muskets, bolt-action rifles, cowboy six shooters and the most prized toy firearm of them all—the machine gun! Chances are if you were a boy (or perhaps a girl) growing up between the 1930s and the 1980s, you remember those toy machine guns, which were arguably the envy of every kid who didn’t have that pretend heavy weapon in their toy arsenal.

History of Toy Guns

The concept of a toy gun is actually a fairly new one, and while there have been toy soldiers in one form or another for eons, it was only in the 19th century that the “toy gun” emerged. Part of the reason is owed to the fact that many children certainly didn’t experience a childhood that included a lot of playtime. This was true for the working classes, where many children began to work at a young age. Those rural children were more likely to handle a real firearm for the purposes of hunting to help put food on the table.

The upper class and even the gentry also likely hunted but more for sport. Finally, there was the fact that the military in many nations was a career—but few boys “played at war.”

This changed as the middle class grew in the 19th century, and one of the earliest mass-marketed toy guns was the “rubber band guns,” which were first introduced in the 1840s. Stephen Perry is credited with patenting the rubber band gun in March 1845, and it began the childhood love affair with pretend guns.

Even in the latter half of the 19th century in the United States youngsters were more likely to have their own actual firearm than a toy. In fact, the original Daisy air rifle was first introduced in 1888, and it was marketed door-to-door to farm families as a “first gun” for young men (and perhaps a few young women).

Post-World War I and the Toy Machine Gun

Machine guns were truly an innovation spawned from the technological leaps of the Industrial Revolution. Invented just 4 years before the Daisy air rifle, the Maxim Gun was the first successful machine gun. According to the legend, its inventor Hiram Stevens Maxim was looking to make his fortune when a fellow American he met in Vienna suggested, “Hang your chemistry and electricity! If you want to make a pile of money, invent something that will enable these Europeans to cut each others’ throats with greater facility.”

In 1884 Maxim patented the machine gun, which was soon adopted in one form or fashion by the major powers of the world. While it would take another 30 years until its potential was truly unleashed—during the First World War (1914-1918) the machine gun quite literally ended the lives of millions of men.

The devastating firepower of the machine gun meant that the armies dug in, and then each side scrambled to find smaller but equally deadly weapons; by 1918, the “submachine gun” was born. One of these inventions was General John Thompson’s “Annihilator”—rebranded the Thompson Submachine Gun after the War. Sales of Thompson’s weapon were slow, but by the end of the 1920s it was soon adopted by criminals—and used by Al Capone’s gangland enforcers in the 1928 St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

By the 1930s, gangsters were popular villains in the movies, and while this was long before the days of officially licensed merchandizing, toy companies such as Marx’s began to market gangland toys to youngsters. The first toy machine gun is believed to be the Marx’s Sparkling “G-Man Tommy Gun,” which featured a tin assembly and real wood stock. It included a drum machine and when “fired” a spark was produced on a flint located under the front sight.

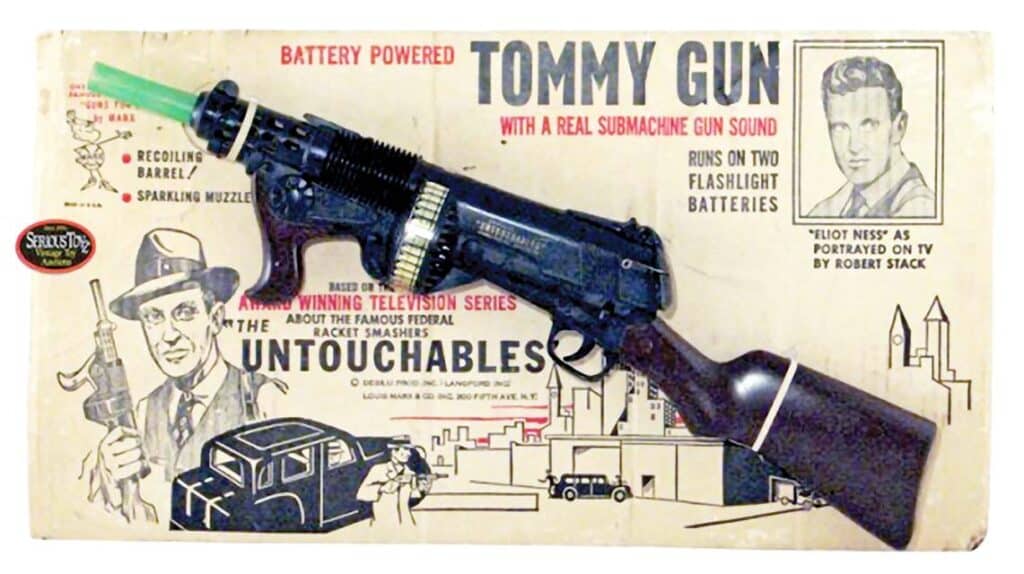

The G-Man/gangster theme continued with Marx after World War II, as the fight to bring down the bad guys moved to the living rooms of America with TV’s The Untouchables. Marx released the hard plastic “Untouchables Tommy Gun”—a 23-inch long toy that was originally only available as a Sears or Montgomery Ward exclusive. It retailed for $2.79 when it was released in 1959, and this may have been the first official toy machine gun tie-in with a TV show. The packaging featured an image of Elliot Ness played by Robert Stack!

These early toy machine guns were loud and colorful with designs that were a bit “art deco,” and it is safe to say that Marx took wide latitude with the designs. While labeled “Tommy Gun,” the generic go-to word for the day (probably like how to anti-gun politicians every black gun is an AR today), these barely resembled an actual Thompson. However, it has been suggested that this was in keeping with the themes from comic strips and comic books of the day where the guns on the printed page also rarely resembled any gun from our reality.

The other factor may have been that Marx as a toy maker didn’t want the toy guns to closely resemble actual firearms—especially after the passage of the National Firearms Act of 1934, which was the first serious legislation of firearms in the United States. The toy maker may have feared there would be a backlash and sought to go with a more “artistic” or “stylized” take on the toy guns.

Cold War Toys

Marx wasn’t the only company to produce little weapons for kids in the post-World War II era; beginning in the 1960s there was some serious competition from Mattel, Inc.—the company that would go on to create Barbie!

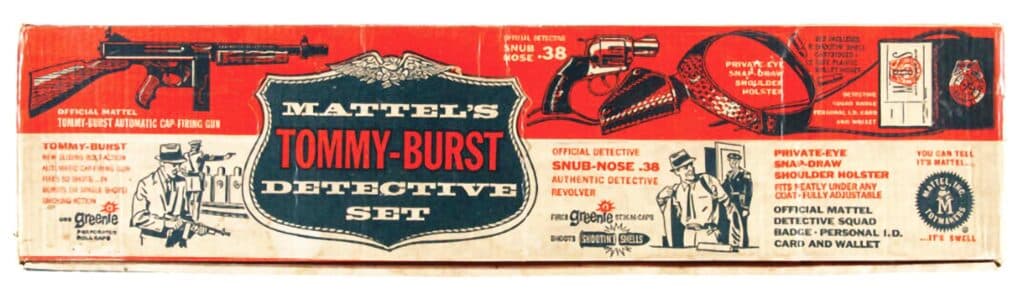

The Mattel “Tommy-Burst” machine gun was introduced in the 1960s, and it far more closely resembled the actual weapon. The stand-alone “Tommy Gun” was marketed for around $3.95, while the Guerilla Model, which featured a camouflaged version complete with soldier strap, was marketed with kiddie binoculars, a case and a toy hand grenade. That deluxe version sold for $7.95.

The toy gun was released to coincide with the popularity of the World War II TV series Combat, starring Vic Marrow as Sgt. “Chip” Saunders, who happened to carry the M1928A1 version. Interestingly, the Mattel version was a mix of the M1928A1 with its Cutts Compensator but featured the Thompson M1A1 side charging handle. The “Tommy-Burst” was designed for use with caps, but most accounts were that it performed middling at best. The visuals were clearly what made this such a desired toy in the mid-1960s.

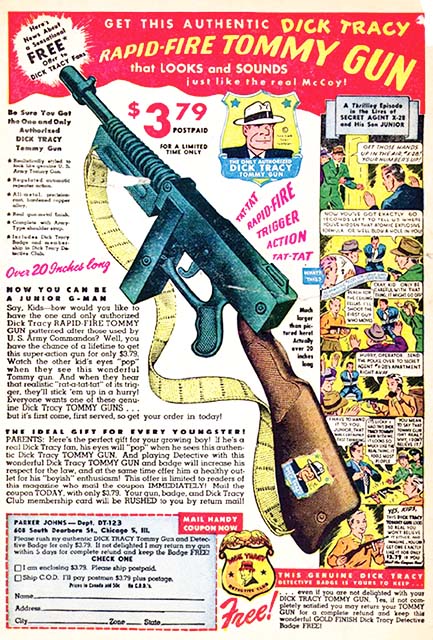

In addition to the Guerilla Model, Mattel also introduced the Tommy-Burst Detective Set in 1961, which featured the 24.5-inch “Official Mattel Tommy-Burst Automatic Cap-Firing Gun,” the 6.5-inch “Official Detective Snub-Nose .38” revolver, a “Private-Eye Snap-Drawn Shoulder Holster,” and a “Detective Squad Badge, Personal I.D. Card and Wallet.” The fictional Dick Tracy™ had been a mainstay in the comics for decades, and Mattel rebranded its Thompson toy accordingly. About the only difference from the other models was the official “Dick Tracy” sticker on the stock. Interestingly Tops Plastic Company also produced a water gun version that was solid red plastic, but for collectors, the Mattel version is the more desirable today.

The detective toys of the 1950s and early 1960s eventually gave way to spy toys, influenced by the arrival of James Bond and similarly themed suave secret agents. While real-world intelligence agencies dealt with issues such as the Berlin Wall and the Cuban Missile Crisis, kids were able to play with Bond-styled gizmos and gadgets.

Multiple Toymakers/Multiple Plastics Corporation (MPC) started this trend in 1962 with a James Bond attaché case based on the one that 007 carried in “From Russia with Love,” while Topper Toys responded with “Secret Sam,” an attaché case that fired plastic bullets and had a working camera. MPC then upped the spy-vs.-spy ante with “B.A.R.K.,”—the “Bond Assault and Raider Kit,” which featured a mortar and rocket pistol.

Topper Toys came out with a real topper in the form of 1964’s Johnny Seven OMA (One Man Army), which became the best-selling boys’ toy of 1964. Marketed heavily on TV, it was unique in that it would transform into seven different modes including grenade launcher, anti-tank rocket, anti-bunker missile, repeating rifle, Tommy Gun and automatic pistol. As many of these “rounds” fired from the gun, Topper marketed additional spare ammunition and also introduced “accessories” that included a Johnny Seven helmet and walkie-talkies!

While Johnny Seven OMA was a huge hit with kids, and has been a staple in popular culture over the past 5 decades, it is notable that Bob Keeshan of Captain Kangaroo refused to allow the TV ads to appear on the show. Apparently the Captain wasn’t of the military-themed variety in the least. However, the toy was actually satirized in an episode of the spy farce Get Smart.

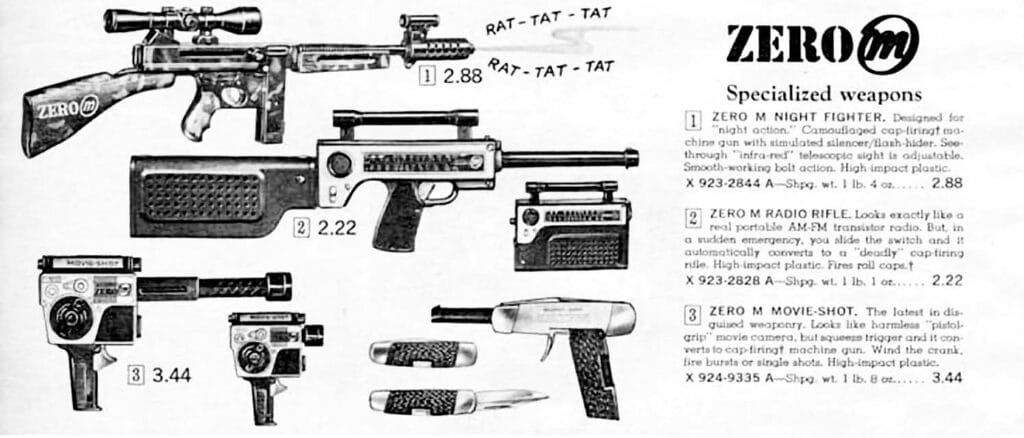

Mattel also joined the Cold War fray with Agent Zero—a character not quite as iconic as Bond but still notable for the fact that he was played in a series of commercials by a young Kurt Russell. The product line included the “Zero M Radio Rifle,” which was a working AM-FM radio, because apparently spies wanted to catch some tunes while on a mission; but the “must-have toy” was the “Zero M Night Fighter”. Essentially another Thompson, it was marketed as being designed for “night action” and featured a camouflaged design and scope.

By the end of the 1960s, Mattel had marketed its scaled down Thompson submachine guns under a number of monikers, and the “Zero M Night Fighter” was marketed as the Mattel Marauder Division Tommy-Burst Automatic Cap Rifle, which was the same as the above model but with a faux wood stock and a special division insignia! Another standout from Mattel was the strangely named “Tommy Burp Mattel-o-Matic Cap Gun,” which was similar to the early “Burst” model but in new packaging.

Marx also introduced its own version of the Tommy Gun, which was released in the U.K. and later the United States. Unlike its early models, the “Trigger Action Tommy Gun” actually did resemble the actual Thompson—and the designers likely copied the Mattel version as it is a similar hybrid of the Thompson M1928A1 and M1A1 models.

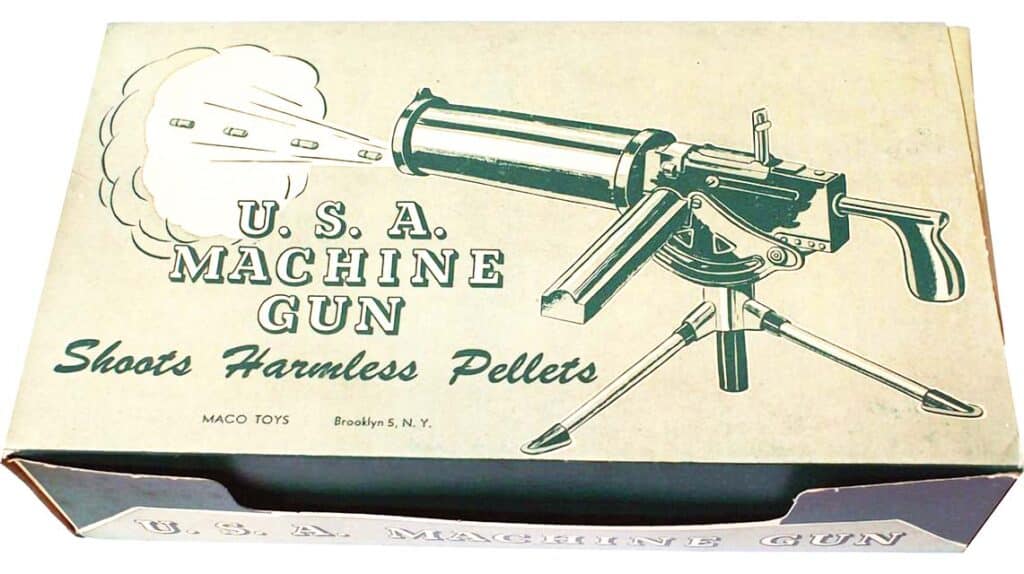

Most of the toy guns of the era were certainly in the submachine gun category—but a few companies did produce some “heavy” weapons. One rare example was Maco Toys’ “U.S.A. Machine Gun,” a fairly accurate version of the M1917A1 water-cooled machine gun complete with tripod. It even shot “harmless pellets!”

The Toy AR

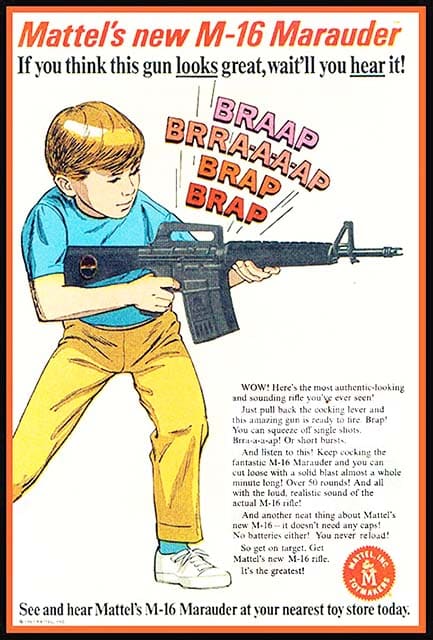

Mattel would use the Marauder name on another toy—its 1966 Mattel “M-16 Marauder”, a pint-size assault rifle that was marketed for not needing caps, never needing to be reloaded and didn’t need batteries. Instead, it featured an internal mechanism that created the sound of automatic fire, no doubt annoying parents nationwide.

The “M-16 Marauder” is somewhat infamous today among the less informed who insist Mattel manufactured parts for the actual Eugene Stoner-designed Armalite AR-15/M16. According to some sources dating back to the 1980s, “the handgrip of the M16 rifle was made by Mattel.” This is a complete myth, but apparently some soldiers joked about the synthetic parts on the real M16; a running joke was, “You can tell it’s Mattel.” The fact that the M16 arrived in Vietnam as the toy “M-16 Marauder” hit the market likely only confused the issue.

Mattel wasn’t the only company either to market a toy version of the battlefield weapon, and in 1967 Marx introduced its own “Sound-O-Power” line that included its M16 Military Rifle, a battery powered toy that featured a speaker in the stock to project the sound of gun fire.

A 1960s-era Maco Toys’ version of a Browning M1919 machine gun, which fired plastic pellets decades before “airsoft” became a thing.

Toy Gun Control

The Vietnam War was not surprisingly hard to market, and by the 1970s, war toys weren’t exactly in vogue as much as they had been. The 12-inch G.I. Joe figure transformed from soldier to adventurer, and due to the energy crisis and oil embargo of the late 1970s, he was retired. When Joe returned in the 1980s he was reduced in size—but that just presented an opportunity for vehicles and other playsets!

Toy guns faced other issues, including calls for bans. In fact, New York City had banned black, blue and silver toy guns since the 1950s—but for the record, pinball and early video games were also banned. By the 1980s—due in part to a few tragic cases of mistaken identity where children and teens were shot by police—toy guns were the subject of federal legislation.

U.S. Code §5001, included in 1986, states that “each toy, look-alike, or imitation firearms shall have as an integral part, permanently affixed, a blaze orange plug inserted in the barrel of such toy, look-alike, or imitation firearm. Such plug shall be recessed no more than 6 millimeters from the muzzle end of the barrel of such firearm.”

Today, all toy guns transported or imported in the country must have this blaze orange tip, or the whole toy must be of transparent construction.

Remembering the Toys

While many of the animated TV series of the 1980s—from G.I. Joe to The Transformers—were little more than half hour commercials designed to sell action figures, in the 1960s the toy commercials were like short movies designed to build interest in the toys. As noted, a young Kurt Russell hawked products, and selling toy guns to kids wasn’t seen as wrong in the least.

“These toy guns were marketed on TV and in catalogs, as well as the daily newspapers,” said Jeff Owenby, who collected the toys as a child and has documented the toys online. “The toys were marketed as singles and in sets, with the sets being very popular around Christmas time.”

While many of these toys retailed for just a few dollars in the 1960s and early 1970s, today collectors have to shell out big dollars—a Mattel “M-16 Marauder” in good condition can sell for more than $500 on eBay, while the really early toys from the 1930s can exceed $1,000 with original packaging.

One irony is that back in the day, even if the toy versions weren’t quite accurate, most kids didn’t know the difference—but thanks to movies and video games what kid doesn’t know an AR from AK. However, Owenby said he has fond memories of the “Tommy-Burst” and added, “It was a close replica down to the smallest detail.”

In the 1960s when Owenby was growing up he said the sight of a kid with a Tommy Gun wouldn’t even turn heads. “Back then, these had red tips but all the kids took them out of them. But you could walk down the street with a toy gun, and the neighbors wouldn’t think anything about it!”

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V24N4 (April 2020) |