By Douglas Olson

In the few years of its existence, Qual-A-Tec developed a reputation as one of the most innovative developers of suppressors. Very little was written about their products since they were almost exclusively sold to the U.S. Military and the majority of those went to the Navy. The shield of secrecy was tightly held between the media and the user. I will not violate that shield and will instead try to describe the technologies that were developed.

Let me digress for a few moments to relate how I became involved in the Qual-A-Tec saga. Unlike many silencer designers, my involvement in suppressors came as a result of my job and not from some personal desire to build suppressors for myself. As a mechanical engineer working for the Naval Weapons Support Center, Crane, Indiana, I was assigned to work with the Joint Service Small Arms Program (JSSAP). Major David Baskett has to take the blame (or credit) for getting me involved in suppressors. He worked for JSSAP at Picatinny Arsenal and had become involved with trying to support the Special Operations Forces with special small arms developments. We worked together to establish a group within JSSAP whose job it would be to perform special developments for low demand weapon systems (including, of course, suppressors). We traveled the country searching out suppressors that could be useful for these special military operators. This effort started in the late 1970’s and to those who remember, there was not a lot of suppressor development going on in this country at that time. I recall that the 22 caliber Suppressors that we looked at were all 1.38 to 1.75 inch diameter cans with flat washer baffles. While they were relatively quiet, they were large, heavy and bulky. Looking back, there has been a tremendous amount of improvement made in suppressor technology in the last 20 years. I will try to relate my experiences throughout this “golden age” of suppressor development. I am not a historian, and did not do a good job of documenting the suppressors I evaluated so my look at this history is from the technological developments.

The suppressors of the 1970’s were primarily of two styles. The Navy was using the S&W pistols with the “Hush Puppy” wipe style of suppressors. This System had been developed by the Navy at White Oak and had inserts made with polyurethane wipes and special subsonic ammunition. The problem with the system was that the chamber pressure of the cartridges was quite high (loaded by Super-El) and that led to problems with ejecting the round after unlocking the slide. The other problem was that the terminal effects were poor. I recall a report from a SEAL who had the task to take out the “guard goose” at a Village in Vietnam. He shot the goose twice with the Hush Puppy and only succeeded in making the goose mad and very noisy. Obviously, this lack of lethality led to the guns being left behind during “real” missions. The other suppressors were a mixture of rather simplistic flat washer type baffles in rather large diameter tubes. Many were made from aluminum to keep the weight down and almost universally were not well suited to the real life missions of the military user. What was clearly needed was a real system. Unfortunately that approach was not to become a reality for quite a few years.

The advent of limited partnerships and capital write-offs for R&D expenses lead to some creative funding for a serious development of suppressors. Charles A. (Mickey) Finn met tax attorney Frederick R. Schumacher who set up these limited partnerships to fund development of suppressors specifically for military customers. Qual-A-Tec was the corporation formed to perform this effort. As one of the military customers, Crane took advantage of the offers from Mickey Finn to try and develop new technologies. This happened simultaneously with Richard Marcinko forming up his “Mob Six.” So here was a user in need of new good hardware and a developer in need of a project. Each needed and used the other. This was far from a marriage. It was more a case of consensual intercourse. When Maj. Baskett and I first tested Mickey Finn’s suppressors they were quieter than anything else we had found. At that time he was using simple flat washer baffles spaced at approximately .25 inches. The rear baffles usually had four holes near the outer edge that helped keep the decibel reading lower, but the real key to the suppressor’s performance was keeping the bore though the suppressor to an absolute minimum in relation to the projectile diameter. The 20 or more baffles of course added a lot of weight to the system. While I was still at Crane, Maj. Baskett arranged for me to take one of these to Washington for a demonstration to some clandestine operators. Being young and naive I put through the travel orders and carried the suppressed .22 Ruger pistol to Washington National. I met Dave at the entrance to the Pentagon and we proceeded to go inside to conduct a demo in one of the vaulted rooms. Phone books were gathered and used as the target. I remember everyone present was duly impressed. After the test I packed the gun and ammo into a tote bag and out the door we went. Dave and I repeated the tests later that night at the hotel room and the next day I was back in Indiana. Looking back, I see how utterly stupid one young engineer can be. I guess that by that time I was hooked. Not so much on the desire to develop suppressors but to try and help the Special Operations users. There was so much clandestine paranoia that the user simply would not go out and find the best suppressors available. That has changed a lot in the last 15 years due to the formation of USSOCOM. Back in the 70’s and early 80’s each Special Operations Group choose its own sources for specialized hardware and these sources were closely guarded secrets. Each group wanted the ability to claim that they were better equipped to handle a specific task than another group. This rivalry really held the total development process back. Things have greatly improved. Today there is open competition and users writing well thought out requirement documents. Today’s Special Forces operators are getting much better equipment than those in years past and more will come home from their missions because of it.

Mickey was able to get a few small contracts with Crane. One of the first involved was a .50 caliber Suppressor for a SS41 German rifle that came from the Aberdeen Museum. Crane took an accuracy barrel and sent it to Mickey along with a drawing. Mickey had located a lathe that could form the dual start course pitched metric thread. This weapon was used to establish the base line characteristics for a .50 cal. sniper rifle. Mickey built a suppressor that was used for the proof of concept. This suppressor was a large aluminum affair with titanium flat washer baffles. The first time we tried to mount this suppressor to the rifle happened at the SEAL’S Desert facility. The threads for the suppressor had not been machined properly, but because it was hard to tell whether it was fully seated on the weapon or not we decided to test it. The first shot was fired by myself and it launched the suppressor 20 to 30 feet down range. Needless to say the recoil was quite severe. The suppressor was only a little worse for the error and by the next day was properly mounted and successfully tested. This was probably the first successful .50 cal suppressor ever built.

Mickey also got another contract to improve suppressors for Ingram MAC 10s and the Hush Puppy’s that Mob Six needed. The Ingram suppressors were taken apart and the aluminum spiral cut baffles were replaced with flat washers and spacers. Testing showed that the sound pressure level reduction was improved by six to eight decibels. For the Hush Puppies a baffle was added behind the wipe unit and that improved its reduction by three decibels. The problems happened when the users started using the guns hard and didn’t keep the suppressors locked on the guns tight enough. To anyone who has handled an Ingram much it is easily seen that the alignment goes to heck very rapidly when the suppressor gets loose. The original spiral baffles had a tubular bore from one end of the suppressor to the other. This guided the bullet out of the suppressor whether the suppressor was tight to the weapon or not. The washer type baffles did not do this and eventually a round exited the side of one of the cans. The first of many lessons I learned about the SEALS is that they do not take particularly good care of their weapons. To many who look at their machine guns as investments or objects to study, realizing that the SEALS look at them as disposable tools, made to be used and abused as necessary is a revelation. To SEALS, there are two types of tools, shit and good shit. Shit tools have to be carried, cleaned, maintained and still don’t work right. Good shit needs minimal cleaning and maintenance and does its job, as advertised, every time. Good shit doesn’t get in the way of “Miller Time”. Once this got properly engraved into my mind I started looking at suppressors (and other weapons) from a different light. What must this tool become to be truly useful to these users? That became the driving force behind all of my future suppressor designs.

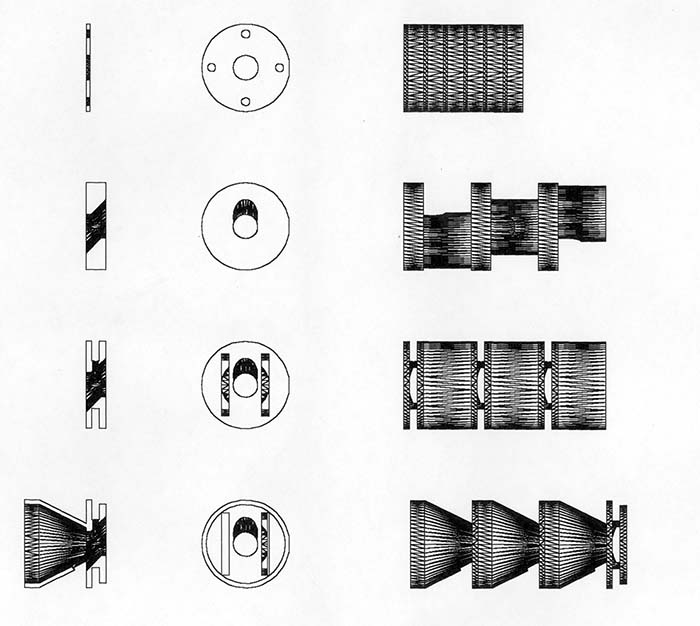

I had my mid-life crisis, resigned from Crane and went to work for Mickey Finn at Qual-A-Tec. This was not a financially advantageous move on my part and I owe a lot to my family for supporting this choice. I have to look at this as another educational experience on my part. Because Qual-A-Tec didn’t have to show a profit, we were able to devote a lot of time and money to improving suppressor design. Mickey is a very talented man and had a good analytical mind that understood the goals of improving the workings of suppressors. We were able to build and test two or three different designs a day for a couple of years. All of this resulted in a very good suppressor education for me. I mostly documented what was accomplished and had input into the development experiments. I also helped prepare and proofread all of the patent applications. Bob McDonald came to the company a little earlier than I did. Bob ran the shop and built most of the experimental hardware. He also provided input into the design but primarily brought forth new manufacturing techniques. Other people were involved but this was the core of the design effort. The first big breakthrough was the thicker flat baffle with the angled hole through the center. This baffle proved so effective that the diameter of the suppressor tubes were able to be dramatically reduced. I think that each baffle design has an optimum diameter associated with it for each caliber. It became apparent to us that this new baffle had to have higher gas pressure behind it to optimize its performance.

Let me digress a bit here to discuss some of the physics that makes a suppressor work. The measure of the sound from a suppressor is a measure of peak pressure at the muzzle exit caused by the escaping gas and projectile. A suppressor’s job, then, is to keep the pressure at the muzzle at a minimum. The first applicable physics equation is: pv=RT ; also known as the ideal gas law. In that equation p is pressure, v is volume per unit weight of the gas, R is a gas constant, and T is temperature in Degrees Rankin (degrees Fahrenheit plus 459.69). We are obviously not dealing with an ideal gas but some generalities can be made from this equation. First is that if you lower the temperature of the gas you lower the pressure. Likewise if you increase the volume in which the gas resides you also lower the pressure. The next thing that physics will show you is that turbulence causes flow to be reduced. Thus two things that a suppressor must do well are to take the temperature out of the gas and to restrict gas flow by causing turbulence. More efficient suppressors (in terms of decibel reduction) will get hotter in fewer shots than inefficient suppressors. This of course can lead to problems in suppressors for full automatic firearms. That is why material choices for suppressors are so important. They must absorb the heat from intimate contact with the gas as it travels through the suppressor yet conduct that heat rapidly to the outside of the suppressor. There are a few suppressor designers who think and even have patented suppressors based upon other concepts such as noise cancellation. I believe that the performance of their suppressors can be better explained with the physics of temperature reduction and turbulence creation. By the way, this education took several years to sink into this thick skull of mine. Of course knowing this will not make you a good suppressor designer. Applying these physical principals to hardware is still difficult. Looking at suppressors from this aspect will, however, lead the designer to better suppression concepts.

The suppressors which were developed at Qual-A-Tec began to shrink in total volume as the slant face baffles were improved. The spacers between the baffles also have a direct bearing on the efficiency of the suppressor. Like everyone else we started with simple tubular spacers of various lengths. The next generation we fondly called the “crank shaft” because the spacers were welded to the baffles and were undersize tubes with a single port that aligned with the output flow from the slanted baffle. The baffles were sometimes rotated 90 degrees at each baffle thus the crank shaft shape. These suppressors worked well in rifle calibers and some were built in 9mm as well. The next big step forward was the addition of a deep cut into the thickness of the baffle. This cut was joined with cuts from the back along the sides of the angled central bore. Three holes were then drilled to allow the gas which got compressed into this chamber to flow downward along the angled central bore. These baffles had some structural problems, which were eventually cured by adding strips of tubing between the two walls. We again went to the spacer design to gain some more sound pressure reduction. The final choice was a cone that was machined directly on the end of the baffle. This proved to be very quiet but lacked the structural strength to prevent the baffle from collapsing on itself when the pressures or temperatures of the suppressor got too high. This baffle was licensed to H&K and people familiar with their products from the mid to late 1980’s will recognize this baffle.

Qual-A-Tec made some significant advances in the state of the art of suppressors in the few years it was in existence. It probably built less than 500 suppressors and most of those went to military customers. Very few of these suppressors ever made it into private hands except as products built under license by H&K and AWC Systems Technology. It obviously takes a lot of business savvy to make a profit in the suppressor market and unfortunately that was not present in the Qual-A-Tec organization. It was an interesting period of time and I learned a lot from my involvement. Hopefully the military users of the suppressors that have their lineage through the Qual-A-Tec years have gotten superior hardware as a result of this company’s existence.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V1N2 (November 1997) |