By Al Paulson

Organized and sponsored by The Small Arms Review, the 1999 Silencer Trials drew manufacturers, government personnel, scientists, and journalists from around the country to Knob Creek, Kentucky, on October 5 and 6. Even Jane’s Infantry Weapons sent their small arms editor. For only the second time in history, industry leaders came together for a rigorous testing and evaluation of both new and established products. Some folks even brought World War II and Vietnam era silencers for testing. This event was not intended to be a contest with winners and losers, but rather an opportunity for learning. Such a gathering is unprecedented in the small-arms industry, with competitors coming together in a spirit of cooperation to improve everyone’s understanding of the art. In fact, I can’t think of another industry in the United States where competitors come together in a similar show of scholarship and fraternity. I am not only impressed by the caliber of minds in the silencer industry, I am impressed by the spirit of the people within this industry.

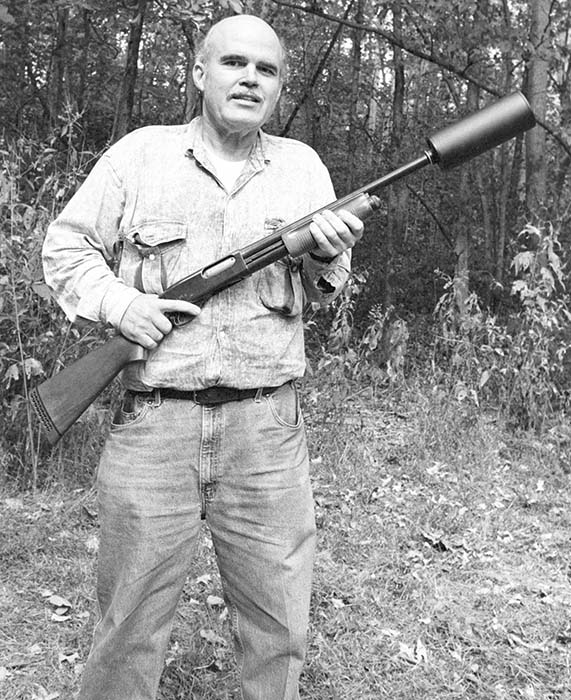

Doug Melton of D.H. Melton Enterprises, for example, really entered into the spirit of the Trials by bringing four new untried prototype designs for his Sound Master suppressed Ruger Mark II pistol, with the intent of selecting the best for subsequent production. He didn’t try to posture before his peers by bringing a really souped-up system that was too complex or expensive for production (unlike some computer manufacturers when submitting systems to computer magazines for comparison with other brands). Melton simply brought four new ideas to see how they measured up to his currently produced design. Melton also brought a newly designed suppressed Ruger 10/22 rifle to see how it compared to his older but outstanding suppressed rifle. He exemplified the spirit shown by the other participants.

Several manufacturers took this sense of fraternal cooperation about as far as it will go, taking apart their silencers for folks to examine. Tim LaFrance of LaFrance Specialties, for example, disassembled his awesome sound suppressor for the .50 caliber Browning M2 heavy machine gun, describing at length the principals of its operation, the R&D that went into its development, and the manufacturing techniques used to carve the complex guts of the device from a solid block of titanium. Can you imagine the major players of any other industry sharing so much information with their peers? I must confess that I really admire these guys as people as well as suppressor designers.

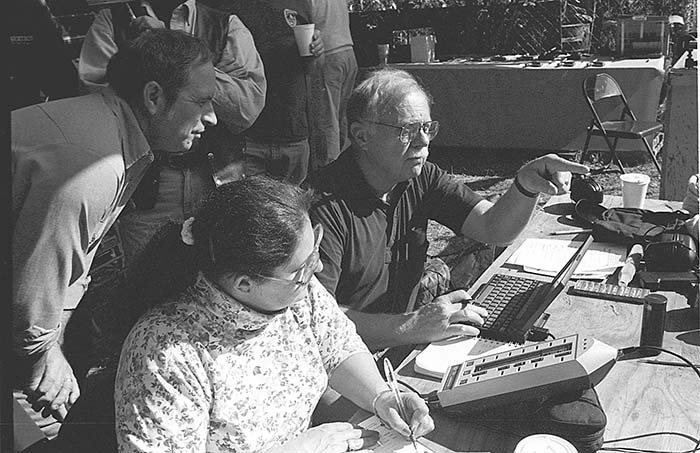

In fact, a lot of exceptional folks made the very ambitious SAR’s 1999 Silencer Trials possible. Everyone pitched in where needed, making this very much a grass-roots effort with a proverbial “cast of thousands.” Dan Shea, the general manager of The Small Arms Review undertook the considerable task of overseeing the event, with Joanne French from SAR organizing all aspects of the event . Dr. Philip Dater, Dan Shea and myself worked out the sound testing regimen. Stan Andrewski worked out the testing regimen for accuracy, with LMO supplying the Ransom Rest. Jeff Hoffman of Black Hills Ammunition donated all of the centerfire ammo used for testing. Two physicists, Drs. Chris Luchini and Reagan Cole, brought the necessary equipment to record pressure versus time data as well as frequency data, providing a whole new level of performance analysis.

So much was going on at once that it took a lot of folks working together like symphony musicians to orchestrate the complex flow of the event. Dan Shea was the conductor, making sure that every player knew what to do when. I was the producer, making sure everyone followed the script and making sure we maintained quality control throughout the data-gathering process. We had five people involved with gathering and recording sound data, two people at any given time handling the shooting and proper alignment of the suppressed firearms (under the leadership of Matt Smith), one person handling the chronograph (three different people shared this assignment), one person moving the firearms from a supervised storage area in the shade to the sound-testing station and thence to the accuracy-testing station, another person handling the movement of data sheets with the weapon and the filling out of duplex targets (one registered behind the other, so both SAR and the manufacturer each got identical witnessed targets for their records), and one person taking the appropriate ammunition from shaded storage to the shooting position.

Another cast of characters took over during the accuracy phase of the testing. The entire process seemed rather like a running of the gauntlet—a trial by ordeal—to those of us immersed in the frenetic nuts and bolts of the event. Occasional hiccups in the process did occur, but the impressive esprit de corps among the participants made working through the occasional problem as graceful as possible. I was quite impressed by the enthusiasm, flexibility and grace of the participants working under difficult technical, logistic and time constraints.

Why go to so much trouble and expense and heartburn? It is true that impartial observers can provide a reasonably satisfactory subjective comparison of suppressor performance when several silencers are compared side by side on the same day. This is how the British National Physical Laboratory compared silencer performance during World War II. Even rigorously conducted subjective comparisons have their limitations, however.

Subjective comparisons can differ substantially depending on an individual’s ability to perceive different frequencies. People who have lost their ability to hear high-frequency sounds, such as an old gunnery sergeant exposed to years of intense impulse noise, might evaluate suppressors quite differently than someone with a normal frequency response. Consider, for example, two suppressors that eliminate different frequencies and yet produce the same peak sound pressure level (abbreviated SPL). For people with normal hearing, the suppressor that is especially good at eliminating the higher frequencies of a suppressed gunshot will seem quieter than the suppressor that eliminates predominantly lower frequencies. The gunny would prefer the suppressor that was better at eliminating low-frequency sound (since he can’t hear the higher frequencies anyway).

There are other limitations to subjective testing. The system breaks down if many suppressors must be compared; it’s just too hard for any person to keep track of too much sensory input. (Ask, for example, any modern fighter pilot about sensory overload in the cockpit during combat.) Then there is the problem of how to describe one’s subjective impression of sound signatures. Descriptions such as “pop” and “whoosh” don’t really convey any useful information, nor do descriptive words conjure up the same mental image to everyone.

Measuring the actual amount of sound pressure produced by a suppressed gunshot and converting the data to a simple scale that mimics the subjective impression of the human ear (the decibel scale) provides a rigorous and objective benchmark that can be compared to benchmarks such as the threshold of human hearing and other sounds of known intensity. Any number of samples can be compared. The decibel reading of the sound pressure level isn’t the whole story, but the SPL represents the most objective single data point suitable for measuring how quiet a suppressed gunshot is. The SPL in decibels also provides the means for comparing that suppressed gunshot to any number of other suppressed gunshots and as well as to the same firearm without a sound suppressor.

Gathering the data for such evaluations is time-consuming. I normally evaluate just two or three suppressors during a typical day at the range, when I’m working by myself. Testing scores of suppressors on the same day required a lot of organization, specialized equipment, and—most of all—help from a lot of enthusiastic people.

In terms of the aforementioned equipment, we used two precision impulse meters: a Brüel and Kjaer Model 2209 Impulse Precision Sound meter with a B&K Type 4136 1/4 inch pressure type microphone; and a Larson Davis Model 800-B meter with Model 2530-1133 random incidence microphone. The meters were set to Peak Hold and “A” weighting, with the microphones placed 1.00 meter to the left of the muzzle or front of the sound suppressor. Time domain and frequency domain data were collected using a computerized digital recording oscilloscope built by Dr. Reagan Cole; this system also used a B&K Type 4136 1/4 inch pressure type microphone. Projectile velocities were measured using a P.A.C.T. MKIII timer/chronograph with MKV skyscreens set 24.0 inches apart and the start screen 8.0 feet from the muzzle, and hard copies of the data were printed after each string using a Hewlett-Packard Model 82240B battery-powered printer via infrared data link.

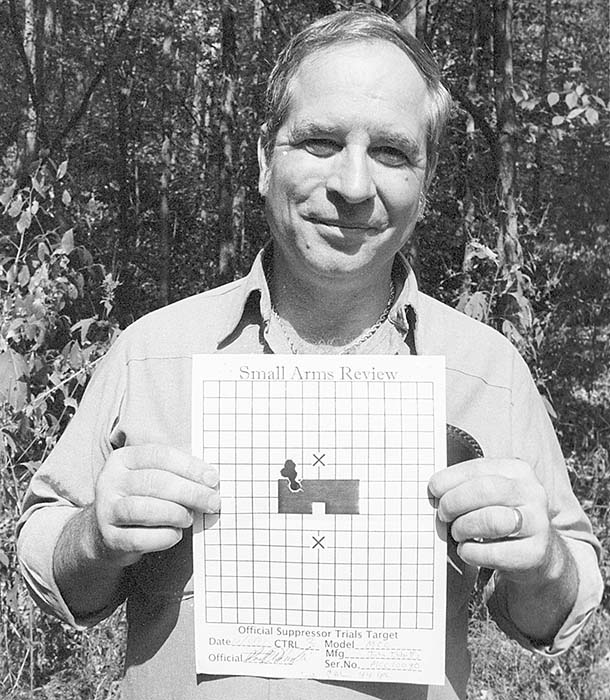

Accuracy testing was conducted to look for design flaws. One of my own suppressed Ruger Mark II pistols, for example, only delivers 4+ inch groups at 25 yards and the projectiles leave oval holes in a target (suggesting extreme bullet yaw), while another suppressed Mark II that I own delivers 1/4 inch groups and perfectly round holes at the same distance. Since these pistols exhibit a ten-fold difference in accuracy, clearly one manufacturer is doing something right, while the other is doing something very wrong. The accuracy testing phase of the 1999 Silencer Trials was intended to reveal such disparities.

Ransom Rests were used for the accuracy phase of the testing, and here the manufacturers or owners of the suppressed firearm were allowed to do the shooting so that they could be confident that the results were as good as possible. Sandbags were used if Ransom did not offer a pistol adaptor for a given handgun.

Stan Andrewski handled the accuracy testing at the trials. The manufacturer removed the pistol grips, and Andrewski mounted the pistol in the machine rest. When the manufacturer was happy with the adjustments, the manufacturer himself would then do the shooting. While the Ransom Pistol Rest is a true machine rest, the rifle rest still depends upon shooter skill. Therefore, manufacturers were allowed to nominate a designated shooter, and a number of them opted for this approach. Mark White of Sound Technology frequently served as the designated shooter, which was a tribute both to his shooting ability and the to respect of his peers. No one seemed to worry that he might do less than his best when shooting a competitor’s system. In fact, White shot a one-hole group using Black Hills .44 Specials with the suppressed Ruger 77/44 rifle made by John’s Guns. Folks were so impressed by the sound reduction and accuracy of this system that three people ordered a rifle from John Tibbetts on the spot.

What about the specific results of the testing? We’re still working on data analysis, which will be published in book form by Moose Lake Publishing LLC, the parent company of The Small Arms Review. We’ll include a brief history of each company, sound and velocity data, detailed descriptions of silencers and integrally silenced guns (including length, diameter, weight, and construction details), plus a photo of each item being tested, as well as the test target used to determine system accuracy. Drs. Chris Luchini and Reagan Cole will contribute a chapter on their frequency and time-domain analyses, Dr. Philip Dater will contribute a chapter on testing methodology and using sound suppressors as hearing protection devices, and Mark White will contribute a chapter on the latest developments in subsonic ammunition for centerfire rifles, including an evaluation of the subsonic 7.62x51mm ammunition from Black Hills Ammunition and Engel Ballistics Research. We’ll also provide a discussion that will try to synthesize all of the data into simple-to-digest conclusions.

We’re also trying to work out some new quantitative ways to compare systems, such as using a plot to compare sound reductions versus velocities generated by integrally suppressed guns, and we may be able to incorporate price versus performance analyses as well. I’m working with several established scientists and engineers to develop meaningful new ways for comparing system performance in easily digested ways. This will take several more months of work. Publication of the book will be reported in a future issue of The Small Arms Review.

For the moment, the bottom line for me is that I was impressed by the state of the art exhibited by all of the participants. Performance that was unthinkable just a few years ago is now commonplace. It was a real privilege to study so many outstanding products, and that study has just begun. My heartfelt thanks go out to the many folks from throughout the industry who made this stimulating and historic event possible. We will all learn a great deal from this considerable effort.

Participating Manufacturers

Black Hills Ammunition, Inc., P.O. Box 3090, Rapid City, SD 57709-3090; phone 605-348-5150; fax 605-348-9827

CCF/Swiss, Inc., P.O. Box 29009, Richmond, VA 29009; phone 804-740-4926; fax 804-740-9599; URL http://www.ccfa.com

D.H. Melton Company, Inc., 1739 E. Broadway Road, Suite 1-161, Tempe, AZ 85282; phone 480-967-6218; fax 480-902-0783

Don Austin Wagenknecht, 12400 Blue Ridge Blvd., Grandview, MO 64030; phone 816-765-2539; fax 913-829-6999; e-mail daw@sprintmail.com

Engel Ballistic Research, 544A Alum Creek Road, Smithville, TX 78957; 512-360-5327; fax 512-360-2652

Gemtech, P.O. Box 3538, Boise, ID 83703; phone 208-939-7222; fax 208-939-7804; URL http://www.gem-tech.com

J.M.B. Distribution, 4291 Valley Quail Street, Westerville, OH 43081; phone 614-891-5784; e-mail JBurg@mailbox.iwaynet.net

John’s Guns, 3010A Hwy. 155 N., Palestine, TX 75801; phone 903-729-8251; fax 903-723-4653

LaFrance Specialties, P.O. Box 178211, San Diego, CA 92177; phone 619-293-3373; URL http://www.NAIT.com/LaFrance

S&H Arms of Oklahoma, P.O. Box 121, Owasso, OK 74055; phone 918-272-9894; fax 918-272-9898

Serbu Firearms, 6001 Johns Road, Suite 511, Tampa, FL 33634; phone 813-854-1532

Sound Technology, P.O. Box 391, Pelham, AL 35124; phone 205-664-5860; e-mail rem700p@sprintmail.com; URL http://www.hypercon/soundtech

Special Op’s Shop, P.O. Box 978, Madisonville, TN 37354; phone 423-442-7180; URL www.compfxnet.com/opshop

Summers Machine Enterprises, 1303 Pauls Airport Road, Thomasville, NC 27360; phone and fax 336-472-6394; e-mail badgerf4@aol.com

TBA Suppressors, 10998 Leadbetter Road, Ashland, VA 23005; phone and fax 804-550-3159; e-mail TBASuppressors@erols.com

Urbach Precision Mfg., 1529 Axe Drive, Garland, TX 75041; phone 972-864-0848; fax 972-864-0571

Young Manufacturing, Inc., 5621 N. 53rd Avenue, Glendale AZ 85301-6011; phone 623-915-3889; fax 623-915-3746; e-mail sales@newriverarms.com, URL http://www.newriverarms.com

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V3N4 (January 2000) |