By Frank Iannamico

The World War II Sten submachine gun, known to the British as the Sten machine carbine, originated as an expedient personal weapon in 1941. One of the reasons for the development of this crude, but effective, 9mm submachine gun was to allow Great Britain to defend herself from an impending German land invasion from across the English Channel.

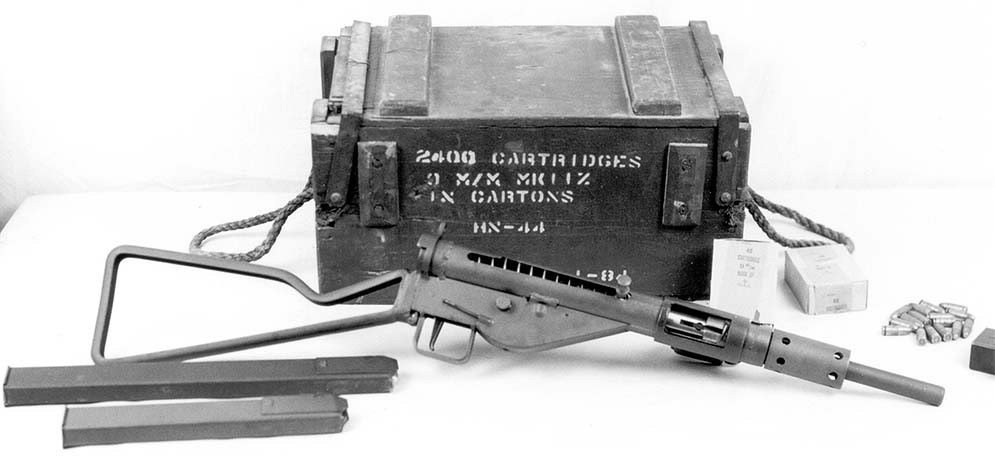

After evolving from the more complicated MK I Sten, the simplified Sten MK II soon became the standard British submachine gun, gradually replacing the Thompson submachine guns that were obtained from the United States early in the war. There were several versions of the Sten manufactured, but the MK II model was the most prolific, making up over half of the approximately 4 million total production of all Marks in the series.

During the early months of World War II, the British Army was not sufficiently up to strength to directly engage the formidable German Wehrmacht. As a result, the British concentrated on sabotage and other clandestine activities against the Germans behind their lines. The handy and readily concealable Sten made an ideal weapon for such covert activities. A suppressed version was quickly developed and fielded. The suppressed Sten MK II was known as the Sten MK II-S model (S for special purpose). The silenced Sten was issued to British Commandos and the Special Operation Executive (SOE). The SOE was a group involved in many surreptitious actions behind enemy lines.

When developing the sound suppressor for the Sten, the designers were faced with the problem of the 9mm Parabellum cartridge’s projectile being inherently supersonic. The speed of the projectile would break the sound barrier when fired. Although this was not normally a problem in standard issue non-sound-suppressed firearms, it will produce a loud “cracking” sound when fired from a sound suppressed weapon. The engineers designed the Sten suppressor to bleed off enough of the round’s propellant gases to slow down the projectile to subsonic speeds. Although the method was successful in eliminating the sonic “crack” other problems arose. Since some of the propellant gases were bled off, there was not enough blowback force to allow the heavy Sten bolt to retract far enough to properly operate the weapon, resulting in short cycling with consequent runways and feeding problems. The suppressor was also prone to rapid overheating after a limited number of shots had been fired.

Reducing the weight of the Sten bolt to a degree that it could successfully operate the weapon solved the functioning problem. This was performed by machining away metal from the center of the bolt’s mass between the two bearing surfaces. The bolt’s recoil spring was also reduced in length by two to three coils if necessary. Each individual bolt was reportedly machined down until it worked in a particular weapon. The nomenclature of a modified bolt was, bolt, breech, MK 3. The bolt was then engraved with the serial number of the host weapon. As a result, the weights of the MK II-S bolts often varied and were not intended to be switched between weapons. The cast bronze-aluminum bolts were reportedly used for the MK II-S Stens because they were easier to machine down in order to reduce their weight. The standard Sten steel bolt is quite hard and very difficult to cut.

While the lightened bolt was successful in operating the subsonic suppressed Sten, using such a bolt in an unsuppressed weapon, although strictly forbidden by the British Army, would naturally raise the cyclic rate of fire. It didn’t take long for an unknown, enterprising modern-day machine gun enthusiast to take note of the lightened Sten bolt, and its affect on the Sten’s cyclic rate. As a result, the concept of the modern Sten “speed” bolt was conceived. The speed bolt is routinely used by today’s shooters to raise the cyclic rate of their Stens.

The standard British Sten MK II, firing 9mm-service ammunition has a cyclic rate of approximately 550 rpm. While acceptable by military standards, I find that slow cyclic rates cause what I refer to as “chugging”. Chugging is my personal terminology for the rocking that occurs between shots when firing weapons with a slow cyclic rate on full-auto. The weapon will momentarily rock to the left (counter clockwise) and then be realigned by the hold of the shooter. I have experienced this condition on several weapons that include the US M3 and M3A1 submachine gun and to a lesser extent, the Russian AK47 and AK74 assault rifles. My personal view (arguably) is that when the cyclic rate is increased to approximately 650 rpm or more, the weapon has a much smoother feel and is easier to control, resulting in increased full-auto accuracy.

While firing a recently obtained Sten MK II, I experienced this so-called “chugging” phenomenon. I began thinking that I would like to have the option to speed-up the cyclic of the Sten.

Class III enthusiast Tony Gooch, a regular attendee at the Knob Creek submachine gun matches, had lent me his lightened Sten “speed” bolt to photograph for the second edition of the “Sten Manual for Collectors and Shooters” book. Although Tony had sent me the bolt to photograph I never weighed or measured it. I put out a call to Tony, who promptly emailed me the specs of his “speed” bolt. He also warned me that the bolts are quite hard and can be extremely difficult to machine.

I took one of my spare Sten bolts over to my local gunsmith Chuck Laugherty. I described to Chuck exactly what I wanted and provided him with the specs. He examined the bolt for a few minutes and then uttered my favorite words: “No problem”. The next day Chuck called to tell me that the Sten bolt was extremely hard and the carbide cutting tool he was using was only removing a few thousands of metal at a time. Not one to easily give up Chuck suggested that he knew someone that could possibly reduce the bolt’s mass by precision grinding. A few days later Chuck sent me an email with a photo of the finished bolt, it looked great. I drove over to his house the next day to pick up my new Sten “speed” bolt. The outside diameter between the bolt’s bearing surfaces was reduced by approximately 11/32 of an inch. This reduced the weight of the bolt by 5 ounces.

The following weekend I packed up my Sten MK II a couple hundred rounds of various brands of 9mm ammunition, my PACT III rate of fire timer/chronograph and headed toward the woods. Upon arrival at the range I swapped out the original bolt and installed the “speed” bolt, the gun fired noticeably quicker and felt smoother.

I then set up the rate of fire timer. A ten-round average with the original bolt yielded an average cyclic rate of 532 rpm. Installing the speed bolt increased the average rate of fire to 667 rpm, an increase of 135 rpm.

Note: The bolt modifications described in this article are for informational purposes only. Modifications to any firearm should only be preformed by a competent gunsmith.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V6N9 (June 2003) |