By Al Paulson

I’ve had a grudging respect for Ingram submachine guns for many years. That respect began when the compact M10/9 was selected over the Uzi for the now legendary Entebbe Raid in 1976, because the Israeli 259 Commandos concluded that the Ingram was a superior weapon for the needs of Operation Thunderball.

Specifically, 259 Commando preferred the Ingram for this archetypal counter-terrorist operation since the M10/9 handled better in confined spaces and since it could be more easily suppressed at that time. I subsequently developed a deep and abiding personal respect for the M10/9 and its smaller descendant, Cobray’s M11/9, because these were two of a meager handful of weapons that I could always rely upon to function with absolute reliability at -75°F (-59 °C) in the wilds of Alaska. Even bolt-action rifles balk at such cold temperatures. The two Ingrams, however, gobbled up everything from modern +P+ subsonic loads to dirty World War II-vintage domestic production without a hitch. Only the Ingrams proved to be completely indifferent to both harsh arctic winters and ammunition of questionable heritage. That said, my Ingrams eventually found their way to permanent residence in my safety deposit boxes because of two shortcomings. The coarse 3/4×10 barrel threads allow suppressors to loosen as they heat during firing, which can result in embarrassing and even catastrophic misalignment. The second problem was that my desire to add state-of-the-art sound suppressors to replace the vintage WerBell-designed cans I had for these guns was checkmated by the fact that nothing really captured my imagination… until now. Gemtech’s new Viper sound suppressor provides a diverse array of compelling features brilliantly conceived for the M10/9 and M11/9 submachine guns.

The Viper has four features I particularly like: (1) precision CNC construction; (2) a novel mounting system designed to keep the can from loosening as it heats; (3) a “floating” grip tube that fits the nonfiring hand beautifully and insulates the hand from what can become a very hot suppressor tube; and (4) a baffle stack of advanced design for maximum sound suppression and service life. Here at last is a sound suppressor worthy of Gordon Ingram’s submachine guns.

Fabricated out of CNC-machined high tensile strength aluminum alloys, Gemtech’s Viper has a similar profile to an original WerBell can, but the Viper is smaller and lighter Furthermore, the Viper delivers vastly more sophisticated engineering and craftsmanship. While keeping the nostalgic look of the WerBell can for those who like the aesthetic appearance of a period silencer, Greg Latka of Gemtech invested two years in this project to solve all of the shortcomings of the WerBell sound suppressor. The Viper is 9.25 inches (23.5 cm) long. The grip tube has a diameter of 1.825 inches (4.7 cm), while the baffle stack is enclosed in a tube measuring 1.375 inches (3.5 cm) in diameter. The grip tube is fully checkered for a very positive gripping surface, which fits the hand comfortably. The entire can is finished in a hard matte black anodizing. Despite all of this advanced engineering, the Viper suppressor only weighs 13.8 ounces (390 grams).

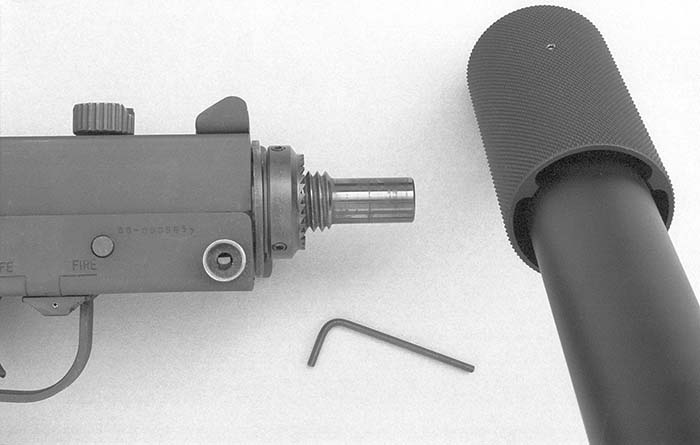

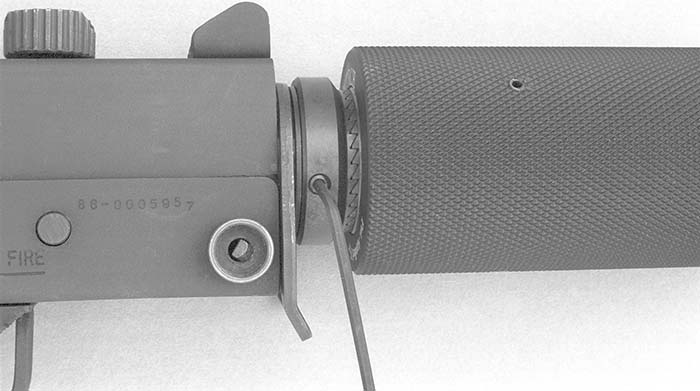

The Viper’s patent-pending mounting system features a separate collar that screws onto the Ingram’s barrel just behind the 3/4×10 TPI (also called 3/4 inch NC) threads, where it is attached with three set screws using the hex wrench which Gemtech thoughtfully provides with each system. The front of the collar has angled teeth that mate with teeth on the rear of the spring-loaded grip tube and keep the suppressor from working loose during firing. This provides an important margin of safety. According to Greg Latka, “the Viper’s mounting arrangement is inspired by the locking-teeth couplers that have been used in the aerospace industry for at least 40 years, but the Gemtech system takes the concept in a valuable new direction. This is what innovation in science and technology is all about.”

Fortunately for end-users, Latka already had special jigs and CNC machinery dedicated to making locking-teeth couplers for aerospace clients, which enabled him to include this technology in the Viper without having to increase the suppressor’s price to amortize this expensive tooling. Using similar technology to what might be found on an F16 fighter adds a level of safety and security for the shooter not found on entry-level cans. The Viper is designed to remain rigidly locked on the barrel whether or not the operator is holding onto the can. That effectively removes the danger of ruining the can and perhaps losing a finger or two if the can loosens and sustains catastrophic baffle contact. That feature alone is worth the price of upgrading to the Viper. Furthermore, the raised grip tube remains cool during firing, which eliminates the risk of discomfort and burns during sustained use. Here’s another feature that can only be termed invaluable. Incorporating these advanced design features makes the Viper more expensive than an entry-level can, but the additional investment is less costly than the simplest of stops at a hospital’s emergency room and represents extremely cost-effective insurance to my way of thinking.

Installing the Viper for the first time may be a bit counter-intuitive for first-timers. To begin, slide the barrel collar onto the raised lip between the threaded portion of the barrel and the strap hanger, but do not tighten the set screws. Next, screw on the suppressor as far as it will go, ensuring that the teeth of the barrel collar fully mate with the teeth at the rear of the suppressor. Push the barrel collar forward as necessary to fully mate these teeth. Now tighten the three set screws. To remove the suppressor, pull the spring-loaded grip tube forward so the suppressor teeth clear the teeth in the barrel collar, and then unscrew the suppressor in a counterclockwise direction. After 1-1/2 turns, the teeth on the suppressor will clear the teeth on the barrel collar, so it is no longer necessary to hold the checkered grip tube forward. The operator can then allow the spring-loaded grip tube to return to its rearward position while continuing to unscrew the suppressor from the barrel.

Once this initial fitting has been accomplished, installing the suppressor merely requires that the operator simply screw the suppressor fully onto the barrel. The spring-loaded grip tube enables the slanted teeth of the suppressor to slide over the slanted teeth of the barrel collar until the two sets of teeth are fully mated, which secures the suppressor into place and ensures proper alignment.

The Viper features CNC machined aluminum baffles of advanced design and a domed front end cap. This design provides excellent performance in terms of both sound suppression and operational life.

Performance of the Viper was tested on a Cobray M11/9 submachine gun using a variety of Black Hills Ammunition including 115 grain RN FMJ, 147 grain flat point FMJ, and a new specially designed submachine gun round which features a 147 grain round nose FMJ projectile. The standard 9x19mm subsonic round found in the Black Hills catalog features a flat point projectile with velocity optimized for pistols. This makes perfect sense because the vast majority of customers buying 147 grain ammo are agencies using the FMJ subsonic round as an affordable equivalent training load to 147 grain hollowpoint duty ammo used in their pistols. This FP ammo is not desirable for use in submachine guns for several reasons. Since submachine guns have greater barrel lengths than pistols, this Black Hills ammo frequently generates a loud ballistic crack in subguns, negating the value of adding a silencer to the weapon. Furthermore, FP or HP ammo doesn’t feed worth a damn in weapons that feed like Ingrams and Uzis because of the abrupt feed ramps found in these submachine guns.

Installing the Viper. (1) To begin installing the Viper for the first time, slide the barrel collar onto the raised lip between the threaded portion of the barrel and the strap hanger, but do not tighten the set screws. Note the “floating” grip tube that insulates the nonfiring hand from what can become a very hot suppressor tube.

Installing the Viper. (2) Next, screw on the suppressor as far as it will go, ensuring that the teeth of the barrel collar fully mate with the teeth at the rear of the suppressor. Push the barrel collar forward as necessary to fully mate these teeth. Now tighten the three set screws.

The new subgun ammo from Black Hills features a round nose for reliable feeding and a slower velocity for effective suppression in submachine guns over a more practical range of temperatures and barrel lengths. This new RN subsonic is not found in Black Hills literature but is being made available to submachine gun shooters as a special service. The 9mm 147 grain RN subsonic round must be ordered directly from Jeff Hoffman, the president of Black Hills Ammunition. It is in stock as this was being written. The first experimental lot could still go transonic when fired in an HK MP5, so subsequent production has not been made quite as hot. This 147 grain RN FMJ ammo is highly recommended for all silenced submachine guns. (Contact Jeff Hoffman, Black Hills Ammunition, Inc., Dept. SAR, P.O. Box 3090, Rapid City, SD 57709-3090; phone 605-348-5150; fax 605-348-9827; URL http://www.black-hills.com).

I’ve been using a single lot of G&L 147 grain FMJ ammo for benchmark sound testing for nearly a decade. It proved ideally suited for use in suppressed submachine guns in terms of projectile velocity, accuracy, reliable weapon function, and gracefulness when fired with a sound suppressor. This G&L round also works well in pistols. Never widely available, G&L ammunition is no longer available. Maybe that’s just as well, because several people have told me that the quality of G&L ammunition went down the toilet during the last few years of production. Therefore, I’ll be using the new Black Hills 147 grain RN FMJ as my subsonic 9x19mm reference standard henceforth. During this transition, however, I’ll continue to report data using both the G&L and Black Hills subsonic 9x19mm ammo so that we all can get a feel for comparing new data with previously published studies.

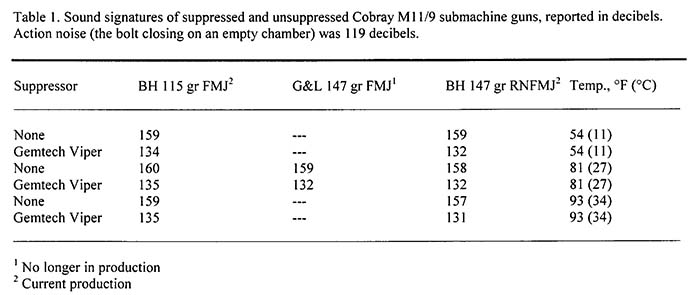

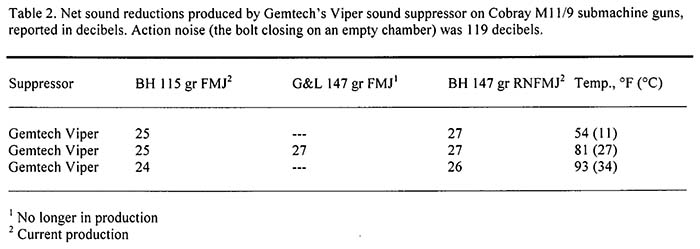

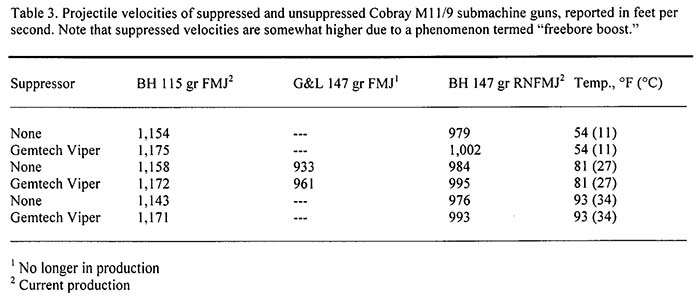

I tested the performance of the suppressor using the specific equipment and testing protocol advocated at the end of Chapter 5 in the book Silencer History and Performance, Volume 1 (Wideworld, Dept. SAR, P.O. Box 2560, Conway, AR 72033; $50 plus $5 s&h, check or MO). Testing was conducted three times, at atmospheric temperatures of 54°F (11°C), 81°F (27°C), and again at 93°F (34°C). Ammunition was kept at ambient temperature in a cooler in the shade until needed. Unsuppressed sound pressure levels (SPLs) were measured 1 meter to the left of the muzzle using a Brüel and Kjaer Type 2209 Impulse Precision Sound Pressure Meter (set on A weighting and peak hold) with a B&K Type 4136 1/4-inch condenser microphone, while suppressed levels were measured 1 meter to the left of the suppressor. Velocities were measured in feet per second using a P.A.C.T. MKIV timer/chronograph with MKV skyscreens set 24.0 inches apart and the start screen 8.0 feet from the muzzle (P.A.C.T., Dept. SAR, P.O. Box 531525, Grand Prairie, TX 75053, 214-641-0049). At least 10 rounds were fired to obtain an average sound signature or muzzle velocity. The suppressed and unsuppressed sound signatures appear in Table 1, the net sound reductions are in Table 2, and the velocity data appear in Table 3.

The first thing that impressed me during the course of the testing was the thoroughly user-friendly design of the Viper. The checkered grip tube provided a very positive handhold that remained pleasantly cool through the shooting sessions, even though the suppressor tube itself got very hot indeed during rapid action drills. Furthermore, I was gratified that the suppressor never loosened during the coarse of the testing. I was also very pleased with the satisfying sound signatures produced by the Viper with both vintage G&L subsonic as well as the new 147 grain RN FMJ submachine gun round from Black Hills Ammunition. Both produced identical suppressed sound signatures (see Table 1). The G&L round was not quite as loud unsuppressed, however, so it delivered 1 decibel less performance when the suppressed SPL was subtracted from the unsuppressed SPL to give the net sound reductions shown in Table 2. It is also noteworthy that the Viper dropped the SPL of supersonic ammo to well below the international safety limit of 140 dB, above which hearing damage is likely when a person is subjected to impulse sound while not wearing a hearing protection device.

I was pleased to note that the new Black Hills 147 grain RN FMJ ammo was more accurate than the G&L round, which was itself very accurate. It was also interesting to note that every round being tested delivered greater velocity when the M11/9 was fitted with the Viper suppressor (see Table 3). The unusual design of this suppressor enables the gas stream following the bullet to continue to accelerate the projectile even after the bullet leaves the barrel and enters the rear chamber of the suppressor. This phenomenon has been termed “freebore boost.”

All of these numbers are interesting, but what do they mean in the real world? In order to see just how stealthy the Viper could be in the real world, I fired three BH 147 grain RN FMJ rounds into the ground (with the selector set to SEMI) while my wife and teenager were watching TV inside a house of standard frame construction that included a glazed wooden door in the wall between us. I was three armspans outside of the door, and they were three armspans inside. Neither lady heard a thing, so I’d say that Gemtech’s Viper is pretty darned stealthy in the real world.

Gemtech’s new suppressor for the M10/9 and M11/9 combines a robust and secure mounting system with a very cool and positive gripping surface, making the Viper both safer and more pleasant to use than entry-level suppressors. These advanced features put the Viper in a class by itself. The Viper also delivers plenty of sound suppression for the real world. Finally, the museum-grade workmanship provides a pride of ownership that only an outstanding product from a company committed to excellence can deliver. Whether you are primarily a shooter or a collector, I can recommend Gemtech’s Viper sound suppressor with enthusiasm. For more information, contact Gemtech (Dept. SAR, P.O. Box 3538, Boise, ID 83701; phone 208-939-7222; fax 208-939-7804; URL http://www.gem-tech.com).

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V5N3 (December 2001) |