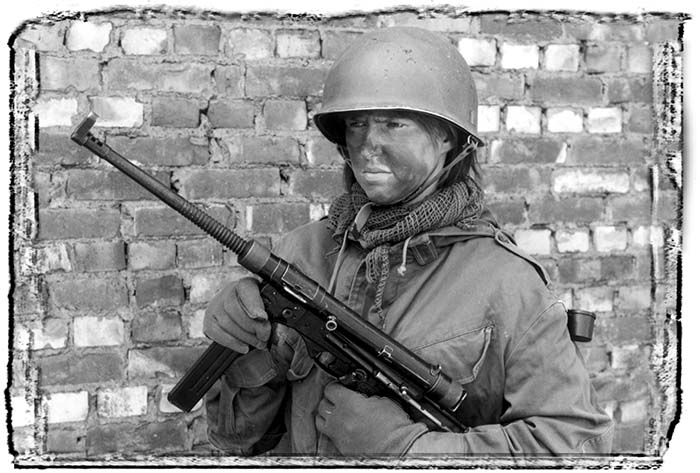

Vigneron with blank firing barrel attached. Photo by Peter Van Meenen.

By Rob Krott

“The small arms were the same as those currently issued to NATO forces, and all were brand-new from Brussels… One in four men was issued with an automatic weapon that was new to me, the Belgian 9mm Vigneron M2 submachine gun. The weapon was light and handy and almost as good as the FN 9mm UZI submachine gun… But the Vigneron had one weakness: the ejection opening cover was a bit tinny and had a tendency to snag on surrounding undergrowth when in the open position.”

– Colonel Mike Hoare, legendary commander of 4 Commando (Katanga 1961) and 5 Commando (the Congo 1964), The Road to Kalamata

Outside its country of origin the Vigneron is a relatively obscure weapon, although Vignerons have cropped up all over the world, from Vietnam to Northern Ireland. When I first read of it in a novel on African mercenaries years ago I thought it was a fabrication. After reading about it again in Hoare’s memoirs I became intrigued. Designed by Colonel Georges Vigneron, a Belgian Army officer, the Vigneron was intended to replace the British 9mm STEN gun. Several STENs were still in service with the Belgians and the Vigneron replaced them in 1953 when it was officially adopted by the Belgian Army. Prior to World War II Belgium forces used the Schmeisser MP 28 II produced by Haenel in Germany. The MP 28 II was also manufactured in Belgium by Pieper and fielded as the Mitraillette Model 34 with the Belgian Army.

The Vigneron (la mitraillette Vigneron Belge or het machinepistool Vigneron) is a rather conventional post-World War design. The Societe Anonyme Precision Liegeoise in Herstal manufactured the first production run of the weapon with some parts being subcontracted to Rocour of Liege. Rocour would eventually take over full production of the weapons. Still other vignerons were manufactured by Brussels firm of Ateliers de Fabrications Electriques et Metalliques (AFEM). According to Mr. Peter Van Meenen, my correspondent from Antwerp and an expert on the Vigneron, the CMH inscription on the grip might stand for Compagnie de Manufacture Herstal, which supposedly made the plastic lower receiver. This is unconfirmed, but is very likely.

An uncomplicated weapon, the Vigneron is a simple blowback selective fire design made from sheet metal stampings and plastic. It is a classic example of 1950s submachine gun production. Firing the 9x19mm NATO pistol round with a muzzle velocity of approximately 380 meters per second / 12224 feet per second it has a cyclic rate of 600 rounds per minute. The Vigneron weights 3.29 kilos/7.25 pounds (unloaded). A fully loaded 32 round staggered stack box magazine weighs .6 kilos, bringing the loaded weight to 8.74 pounds. Fairly heavy for a submachine gun. An M-14 rifle weights 8.7 pounds and in combat, I’d rather have an M-14.

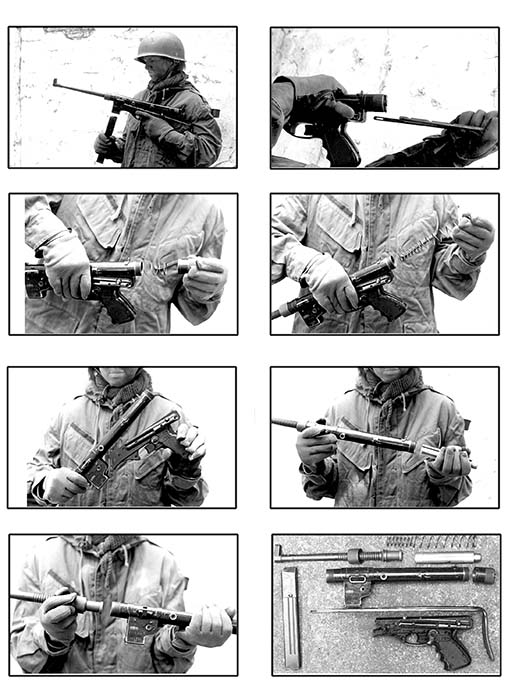

The Vigneron is 890mm/34/9 inches overall with stock extended and 705mm/27.5in with stock telescoped. The telescoping stock is fabricated from heavy steel wire and performs double duty as a cleaning rod: one end of the stock is slotted for bore patches and the other is threaded for a bore brush.

The Vigneron has a long barrel for a submachine gun (305mm/12 inches) but the Vigneron barrel incorporates a compensator and a muzzle brake, making it easily recognized by its cooling fins and compensator notches (located behind the front sight). The barrel has six right hand grooves.

The M1 Vigneron has a blade front sight and a non-adjustable rear aperture. The M2 Vigneron added a protective hood to the front blade sight (it sometimes became bent) and the rear “peep” sight was replaced by a standard notch sight. The top half of the M1 peep sights were simply cut off to leave a notch sight.

Operation

The Vigneron loads and fires like the British Sten. It has a grip safety which must be depressed. The integral grip safety locks the bolt to the rear when not depressed. This prevents accidental discharges should a loaded weapon with bolt forward is dropped or jostled. The selector switch on the left side of the receiver has the usual three settings: semi-automatic, automatic, and safe. Even while set on automatic a light trigger finger will still be able to get off single shots. The ejection port is on the right and is protected by a hinged dust cover. The dust cover is unlocked / opened by cocking the weapon with its non-reciprocating bolt handle (located on the left side of the receiver).

Identification

The marking on the left side of the magazine housing “A>B>L>” is an acronym for the Belgian Army (incorporating the French Armee Belge and Flemish Belgisch Leger). According to Peter Van Meenen, A.L. is also found and sometimes the markings are milled off. The last two digits of the year of manufacture are also found here as is the model number of the weapon, either “VIG M1” or “VIG M2”. Some modified M1s may be over-stamped with a numeral two. Below this is the weapon’s serial number. On the reverse side of the magazine housing are markings which denote whether the weapon was issued to the Belgian army or Congolese army. On the Belgian issued Vignerons there is the crest of Belgium, a lion rampant inside double pointed spear-head. The Congolese Vignerons have a lion encircled by laurels and “FP” (for Force Publique, the colonial era Congolese military and police force). Others marked “CB” for Congo Belge (Belgian Congo) were also issued during the colonial administration. Next to the selector switch are the selector markings “A”, “R”, and “S”. My interpretation is A – automatique, R-repeter, and S-securite, i.e. automatic, semi and safe. Above the trigger housing is “Licence Vigneron,” and beyond the selector switch at the top of the pistol grip is “CMH” as already explained. Above that and just to the right of the selector switch’s “S” is an encircled “B” (not found on all weapons).

According to Van Meenen, “The few people I met that fired the gun in anger seemed to like it a lot. I had a chance to shoot it myself when one was issued to me in an artillery unit in the Belgian army in 1986. The then brand new FNC was replacing both the FAL and the Vigneron. By then the aging gun was quite unpopular with the soldiers, mostly conscripts.” The soldiers’ dissatisfaction with the weapon was attributed to its performance and its appearance. “It didn’t look the part because armorers lovelessly touched up the damaged finish with black paint. There were also complaints from people who couldn’t get used to the grip safety, which sometimes pinched the hand and could cause a failure to fire. Rumor went around that if you didn’t screw on the receiver very right, the grip frame could become loose during firing and the receiver would fall on the ground, still spewing out slugs until the magazine was empty.” While his training emphasized the need to always screw the receiver cap back on tightly, Van Meenen says he could never find out if this theoretically possible accident had ever occurred in actuality. The possibility of this mishap was taken seriously enough that modifications were made to the Vigneron used in Africa: a metal tab welded onto the receiver to keep the receiver cap from loosening. Another problem mentioned in a Dutch magazine article, concerns reassembly of the barrel. Because the threads are the same it is possible to put the barrel on upside down or even switch it with the receiver cap…though you’d have to be mechanically challenged to do either. Be that as it may, there is video of an IRA funeral detail which shows one of the IRA terrorists firing a salute from a Vigneron, no doubt hastily reassembled as the escaping gas can be clearly seen exiting the compensator cuts on the bottom of the barrel.

Like submachine guns in most western armies the Vigneron was issued to rear area troops and special forces. Vehicle drivers, armor and artillery personnel, and military police were issued the Vigneron. The ParaCommandos were also issued the Vigneron and used them in action during the parachute assault on Stanleyville, in the Congo in 1964 and on subsequent operations during the Congolese Intervention. Vignerons were already in use during the Simba Rebellion by the Congolese Army (Armee Nationale Congolese, formerly the Belgian officered Force Publique) and the government hired white mercenaries fighting the Simba rebels. After the war Vignerons were supposedly used as close-quarter defense weapons by Union Miniere truck drivers in the Congo. They removed the buttstock and cut the barrel back to the last cooling ring, sometimes even welding the front sight back on.

The Belgian gendarmerie (police) which were part of the armed forces were also equipped with the Vigneron. The police issued Vigneron was replaced by the Belgian made (Fabrique Nationale) UZI in the 1970s and the military replaced theirs with the UZI and the 5.56mm FNC assault rifle. The obsolete weapons were then disposed of in Algeria, Burundi, Congo, Portugal, and Rwanda, although some Belgian Army reserve units still carried Vignerons as late as the early 1990s. The Portuguese issued the Vigneron as the Metralhadora M/961 and fielded them in Mozambique and Angola.

Rob Krott and SAR would like to thank Mr. Peter Van Meenen of Antwerp, Belgium for his assistance in the preparation of this article.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V3N9 (June 2000) |