By Robert Bruce

“Brigadier General Robert W. Daniels, the Army Ground Forces Ordnance Officer from 1942 to 1944, believed the Army was oversold on the carbine. The Army needed a light, powerful weapon, but…the carbine turned out to be about as powerful as a pistol and about as handy as a rifle.” From The Ordnance Department: On Beachhead and Battlefront, L. Mayo, Office of the Chief of Military History, 1968, USGPO

“Light Weight Semiautomatic Rifle”

The .30 caliber M1 Carbine, introduced into the US Army in the first year of U.S. engagement in WWII, quickly gained favor of the officers and men who carried this handy new weapon in training for combat in Europe and the Pacific. Intended as a replacement for the old .45 caliber M1911 automatic pistol and the .45 caliber Thompson submachine gun, it was compact, lightweight, accurate, simple to operate and maintain. But, combat experience soon showed that theory and reality are not always compatible.

In June 1940, on the eve of America’s reluctant entry into the ongoing war with Germany and Japan, the US Army Ordnance Department began a crash development program toward fielding a “Light Weight Semiautomatic Rifle.” After rejecting several entries for various reasons, six prototype designs were extensively tested at Aberdeen Proving Ground in May and June of 1941. Only two test weapons survived; one from the government-owned Springfield Armory and another from Bendix Aviation, although neither could be considered ideal.

Luckily, representatives from Winchester Repeating Arms company — busily making the new ammunition specified by the Army for its Light Rifle — had been on hand for the testing. Soon convinced that their firm should give it a try, Winchester presented a hastily thrown-together weapon on August 8th, 1941.

Subsequent engineering tests and field trails showed the prototype Winchester Light Rifle to be superior in all details. Its basic operating principle was a gas tappet designed by David M. Williams, where a quantity of propellant gas is bled from the barrel and enters an expansion chamber where it causes a short piston to sharply move outward. Not surprisingly, since Winchester was at the same time deeply involved in a crash program to mass produce the M1 rifle, their bolt and locking system was essentially a scaled-down version of John Garand’s excellent weapon.

Carbine

Winchester’s Light Rifle significantly outperformed its rivals and was formally accepted by the Army on October 22, 1941. In order to avoid likely confusion in ammunition and parts supply as well as tactical employment, a distinctive name was called for to separate it from the M1 “Garand” rifle. Since horse cavalrymen had long been armed with short versions of standard rifles called “carbines”, it was decided to officially designate this new weapon as CARBINE, CALIBER .30, M1.

Ammunition

Drawing on experimentation with such familiar rounds as the 9mm Luger, .45 cal. ACP and .32 cal. Winchester Self Loading, the Army Ordnance Corps decided on a straight-sided case for ease of manufacture, feeding and extracting. The “rimless” brass case was necessarily elongated to accommodate a larger powder charge than most pistol rounds. Because this intermediate cartridge was to be used exclusively in a short rifle, its greater power and recoil were readily acceptable.

A relatively light full metal jacket round nosed 110 grain bullet was pushed out by 14.5 grains of IMR 4227 ball powder producing a chamber pressure of some 31,000 pounds per square inch. This had a muzzle velocity of 1860 feet per second and would remain stable in flight well beyond 300 yards. Test experience and manufacturing considerations dictated some changes, and the CARTRIDGE, CARBINE, CALIBER .30 M1 was standardized on September 30, 1941.

War Baby!

With Europe and Asia already embroiled in war, it was obvious to all but the most naive that America would soon be pulled into the conflict. The Army ordered 350,000 from Winchester on November 24, 1941 — just a couple of weeks before the Pearl Harbor attack. As demand for the little rifle exploded, eight other firms — including Winchester — began production. Inland was the major contributor with over 2,640,000 out of a grand total of 6,117,827 carbines of all types by the end of the war in 1945.

Early Production Model

After the usual fits and starts, fixes and modifications, the first real production model Inland guns began rolling off the line in June 1942. This gas operated, magazine fed, air cooled, semiautomatic shoulder weapon was characterized by its walnut “sporter” stock, machined steel receiver, detachable 15 round magazine, and rudimentary “L” type rear sight. Its overall length was 36 inches weighing 5.8 pounds with canvas sling and loaded magazine in place.

Paratroopers

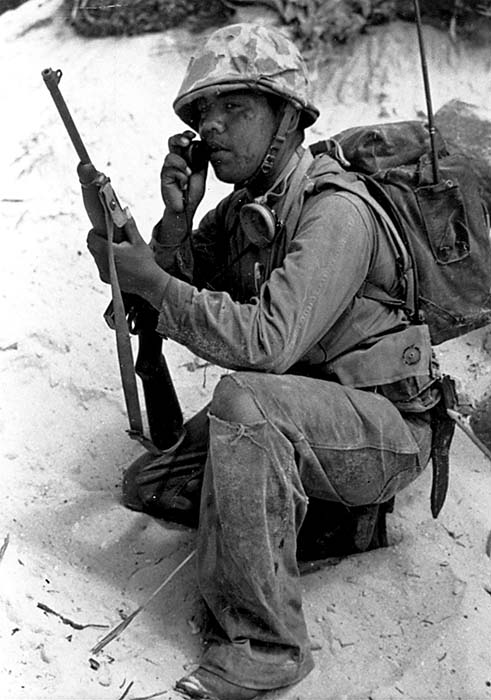

Although originally intended for issue to soldiers manning crew-served weapons such as mortars, heavy machine guns and artillery pieces, the newly formed parachute regiments got most of the first guns off the assembly lines. This was a logical development given the tactical employment of airborne troops as fast moving light infantry. Training exercises had shown the effectiveness of the heavy and sometimes dirt-sensitive M1928A1 Thompson Submachine Gun to be particularly limited by its short range pistol cartridge, and the more powerful M1 Rifle to be too long and heavy. It seemed, at first glance, that the carbine would be ideal….

The M1A1 is the first major modification of the basic carbine. Standardized in May of 1942, it replaced the sporty traditional wooden stock with a metal folding version specifically designed with airdrop in mind. Inland engineer, Paul Hamish, is credited with the winning design, a skeleton frame of heavy wire attached to a modified wooden pistol grip. Folded up, the M1A1 was a compact 25.4 inches, and could be fired almost like a pistol without extending the stock.

Stopping Power?

Although light, compact, accurate and reliable, the M1 and M1A1 carbines were not so successful in battle. Many soldiers and Marines who had eagerly carried these “Baby Garands” in training soon even more eagerly cast them aside for the real thing after their first combat. Simply put, the 110 grain carbine slug had pathetically little stopping power compared to the pointed and fast 150 grain .30-06 bullet fired by the M1 rifle. Enemy soldiers hit even multiple times would often keep coming, causing real life nightmares.

The laws of physics are not to be circumvented, and with Geneva Convention prohibitions against soft point ammunition, there was nothing that could be done to increase the wounding and lethality of the full metal jacket carbine round. About the only avenue for exploration was in ways to increase multiple hits —more holes in an enemy make him more likely to be put out of action.

Selective Fire

It is interesting to note that, while the original concept for the carbine included provision for automatic fire, this was not a feature of the Winchester design. But, the American GI being quite ingenious, field modifications for automatic fire soon came to the attention of Ordnance personnel. According to contemporary reports, these relatively crude attempts tended toward extremely high rate of fire with inevitable controllability problems.

Although a mixed success in combat due mostly to its marginally adequate ammunition, the short rifle was a largely successful compromise between the pistol and the rifle, suitable armament for those whose duties did not require full powered performance. It was not until the advent of the German STURMGEWEHR with its “intermediate” cartridge that the carbine concept was fully validated.

Primary Reference Source: WAR BABY! by Larry L. Ruth, Collector Grade Publications, Toronto, Canada, 1992.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V4N3 (December 2000) |