By Jean Huon

Military history is a fascinating subject, particularly the story of “forgotten wars” such as the Boer War or the Spanish Civil War. Let’s today take a look at the Chaco War.

But where is the Chaco? The word Chaco means hunting in the Quechua language (spoken in Peru). It indicates at the same time a province located in the North of Argentina and also a vast arid and afflicted territory, which is on the Andean plateau that borders on Bolivia to the South and Paraguay to the North. It is bordered in the East by Brazil and the West by Argentina.

When the Latin America countries, independent for only a few decades, had sought to assert their authority, frontier conflicts were not rare. The coastal states of the Gran Chaco desert engaged in hostilities between 1865 to 1870: a coalition formed by Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, entered to war against Paraguay, which was thoroughly beaten.

Seizing the circumstances, Bolivia also asserted its authority over the region. But what is Chaco if not a hostile and uninhabited desert, subjected to infernal climatic conditions. In addition, following the “Nitrate War” with Chile in 1884, Bolivia lost a province of the South that gave it access to the Pacific Ocean. Bolivia then sought to be able to appropriate both the Rio Pilcomayo, then the Rio Paraguay, which converge towards Rio de Parana to join the Atlantic, which was not at all to the taste of the government in Asuncion!

Consequently, border incidents were frequent between the two countries. But a civil war struck Paraguay in 1922. Benefiting from this respite, Bolivia built a line of forts to assert its presence in the Gran Chaco, whose resources remained limited. Until the day when… it was announced that there could be oil in the region.

1927 and 1928 are remembered by engagements between the troops of the two countries, so much so that an international commission was needed; engaging several states in the name of the League of Nations, so that peace returned.

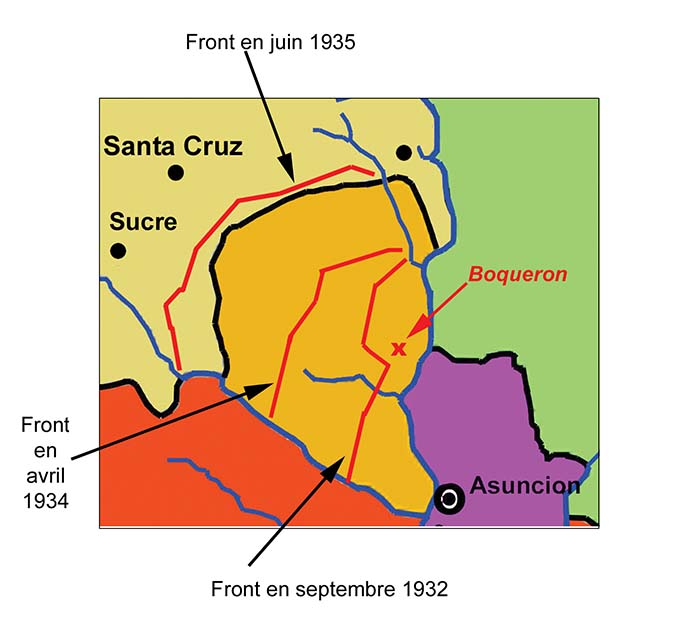

But in a region where there are no roads and little water, life and even survival are difficult. The hostilities began in June 1932, both wished to have control of the Pitiantuta lake and they in turn built Fort Carlos Antonio Lopez, which defends the area. In fact, the fort consists of no more than some log huts reinforced by fill and defended by a ditch. Consequently the conflict escalated and an attempt at international mediation failed. Each of the two countries sent increasingly greater forces. From a simple frontier conflict one passes to a true war, using infantry, artillery, tanks and airplanes. The belligerents then endeavoured to take the forts built by the enemy, in particular those of Corrales, Toledo and Boqueron, which were taken by Bolivia.

Each of the two countries is supported by armament from states who wished for the victory of their allies, with the hope at drawing some political advantage from it. Thus at the time of the conflict, one saw the deployment of material from the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. A truly general engagement in the conflict…

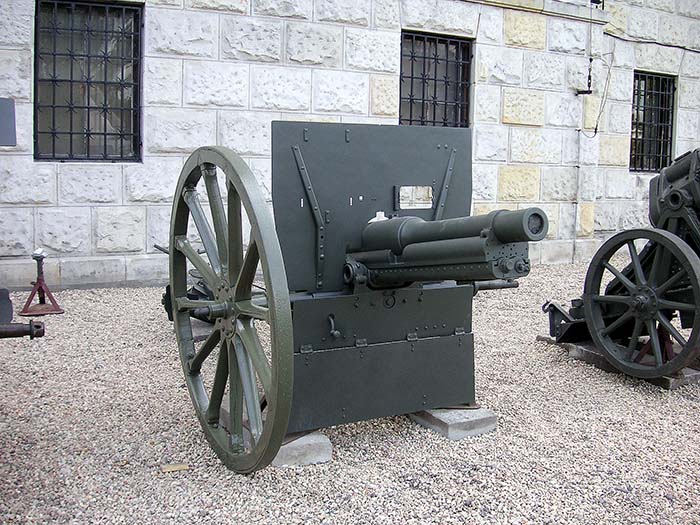

In September 1932, Paraguay launched an offensive and laid siege to Boqueron. The position was firmly defended by Bolivia, which had a garrison there of more than 700 strongly armed men with 27 light machine guns, 13 machine guns, two 75mm Schneider guns, one Krupp mountain gun of the same calibre and two 20mm Oerlikon guns.

The Paraguayan soldiers dug trenches and besieged the position. Bolivian reinforcements manage to penetrate to the fort, but were not able to break out. On their side, the Paraguayans bombarded the unfavourable position systematically. They brought to the ground 24 pieces of artillery and 11 mortars. Deprived of water, food and ammunition, the garrison capitulated on September 29th. The Army of Paraguay captured 820 prisoners.

Encouraged by this victory, it engaged in a new offensive starting from October 8th, with new troops. Although the Bolivians were better equipped than their adversaries, the latter were accustomed to the roughness of the climate and had a better knowledge of the ground. The Paraguayan forces continued their progression towards the North-West, taking forts, capturing many prisoners and a considerable amount of material, which they hastened to turn against their former owners.

The Bolivian Army tried again to gain ground by a counter-attack on November 5, 1932, but the Paraguayans preferred a withdrawal and dodged a confrontation. At this time the Bolivians chose to entrust the command of their army to the German General Hans von Kundt, veteran of the East European war. On the other side the Paraguayans had French military advisers. In the way of material, the Standard Oil Company and the U.S. banks supported sending American, English and German materials to Bolivia; while Royal Dutch Shell forms the link between the British and French armament companies to aid Paraguay. In Paraguay, General Jose Estigarribia took command of the troops. He would become Marshal and later President of the Republic.

The new chief of the Bolivian Army launched several attacks against enemy positions starting December 26, but the resistance of their adversaries permitted them to avoid being surrounded or defeated. In spite of air support, all the offensives of General von Kundt failed, but worse still, the front moved back and the soldiers of Paraguay gained ground.

During the summer of 1933, the Bolivian Army was forced to move back several hundreds miles; it was demoralized and desertions were numerous.

Starting in September, General Estigarribia again took the offensive. He encircled the Bolivian positions, which in accordance with orders did not retreat, but were forced to give up from lack of supplies. Two divisions were thus captured in December. Other units managed to take refuge in Argentina where they were interred.

At the end of December 1933, a ten-day truce made it possible for the belligerents to recover. Once the cease-fire finished, the hostilities began again. Bolivia took the offensive and captured the 2nd Paraguayan division and part of the 7th, which had the imprudence to advance too far from their bases.

The months passed. Each combatant bandaged their wounds and re-equipped themselves. On August 14, 1934, the Paraguay 6th Infantry Division set out again on the attack – it took the offensive and the Bolivian garrisons were trapped and capitulated one after another. General von Kundt was dismissed and replaced by General Enrique Peñaranda. But on November 27th, it was the president of Bolivia, Daniel Salamanca, who was deposed by the chiefs of the Army.

Soon, the major part of Gran Chaco was under the control of Paraguay, who then continued their advance and penetrated into Bolivia in January 1935. At the culminating point of their advance, they were 290 miles from their bases; but they ran out of steam and the two countries we’re exhausted economically and the losses were enormous. A cease-fire intervened on June 12, 1935.

Negotiations began under the auspice of the adjoining countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Peru, Uruguay and the United States. An agreement was concluded on July 21, 1938; most of Chaco Boreal was annexed by Paraguay, Bolivia was granted a right-of-way on Rio Paraguay. The war caused more than 100,000 casualties and others followed in the following years from the epidemics.

The peace treaty between the two countries, was finally signed… in April 2009 by Evo Morales, Bolivian president and the president of Paraguay Fernando Lugo, following the mediation of the Argentinean president Cristina Fernandez-Kirchner.

And no oil was ever found under the Chaco.

Forces involved

Bolivian Army: At the beginning of the conflict, the Bolivian Army had 12,000 men. The uniform of the troops was gray-green, with a belt and cartridge pouches made of leather. Troops had a cap and carried a rolled cover across the chest.

The army consisted of seven divisions. Each one generally had two infantry regiments and one cavalry regiment, with sometimes an artillery regiment and engineers. Troops for the most part were Indians and officers were from the local middle-class. Also, we noted the presence of some Chilean and Czech “military advisers.” At the end of the war, they had mobilized 250,000 men and the losses were 57,000 men.

Paraguayan Army: At the beginning of the hostilities, Paraguay had three divisions, each consisting of two infantry regiments and one cavalry regiment. Other units were independent, particularly artillery and engineers. The army totalled 8,000 men.

The uniform was composed of an olive drab jacket-shirt and pants. All the soldiers did not receive shoes and many went in sandals or bare feet. They were capped with a fabric hat. The army distributed mess tins but as for the remainder (cover, bag, can) each of the soldiers looked after himself.

Foreign mercenaries (White Russian) took part in the engagements, while French pilots flew the planes. At the end of the conflict the country mobilized 150,000 men, gathered in three army corps. The losses rose to 43,000 men.

Weapons of the belligerents

The armament of Bolivia

Small arms: The Bolivian troops were equipped with various material, generally of European origin:

- Parabellum pistol (9×19);

- Mauser C 96 (7.63×25);

- Colt M1911 (.45 ACP);

- Walther PP pistol(.32 ACP);

- Browning 1910 (.32 ACP);

- Bergmann MP 28 submachine gun (9×19);

- Swiss Solothurn SI 100 submachine gun (9×19);

- Bergmann MP 35 submachine gun (9×19);

- Finnish Suomi KP 31 submachine gun (9×19);

- Mauser M1891 rifle, identical to the Argentine model (7.65×53), manufactured by Ludwig Loewe in Berlin;

- Mauser M1895, rifle bought in Argentina;

- Mauser M1907, type Mauser 98 rifle manufactured in Germany (7.65×53), provided by DWM in Berlin;

- Mauser F.N. 1924 and 1924/30 rifle and carbine, weapons made in Belgium (7.65×53);

- Mauser Vz 24, rifles of Czechoslovakian origin (7.65×53); 39,000 rifles acquired via the English company Vickers. One second order related to 45,000 parts and a third on 20,000 others;

- Mauser Export 1933 carbine, identical to the K98k (7.65×53), from Mauser factory in Oberndorf;

- Lewis light machine gun, (.303 British);

- Madsen light machine gun, from Denmark (7.65×53), provided in infantry and aircraft (turret) versions;

- Czech light machine gun ZB 26, (7.65×53);

- British Vickers-Berthier light machine gun, (7.65×53);

- German Maxim machine-gun, (7.65×53), possibly commercial M1909 or rebarreled MG 08) ;

- American Colt M1914 machine gun (.303 British);

- Vickers Class C, infantry water cooled machine gun, 350 specimens between 1928 and 1934 (7.65×53);

- Aircraft Vickers Class E machine gun (18 specimens) and 6 class F between 1928 and 1932 (7.65×53);

- Tank machine guns Vickers Class C/T (7.65×53);

- Browning-Colt MG 38 infantry water-cooled machine gun, (7.65×53), 256 specimens between 1920 and 1938;

- Browning-Colt MG 40 aircraft air cooled machine guns (7.65×53), 207 specimens in 1933-1934.

Tanks and armored vehicles

- Vickers 6 ton, Type A light tank (16,000 lbs) propelled by a 95 hp Puma engine. It had twin turrets; each armed with one 7.65mm water cooled Vickers machine gun. A single specimen was used by Bolivia and it was captured by Paraguay, which exhibited it in a monument at Asuncion. It was returned to Bolivia in 1994 and it is now exhibited at the La Paz Museum of the Military Academy;

- Vickers 6 ton, Standard B. Similar to the Type A, it was equipped with one turret armed with a 47mm gun and a Vickers machine gun. Two examples were used.

- Renault FT 17. A Renault tank was delivered to Bolivia in 1931, but we cannot confirm that it was used in combat;

- Carden Loyd universal carrier Mark IV. British 1.5 ton vehicle, also manufactured by Vickers. Propelled by a 40 hp Ford engine, it could tow a tracked trailer or a wheeled gun. It was armed with a 7.65mm Vickers machine gun. Bolivia received between two and five of these machines.

- Ansaldo L3/33 or 35 universal carriers. Italian 3.2 ton caterpillar vehicle propelled by a 43 hp FIAT engine. It was armed with two machine guns. Fourteen Ansaldo carriers were delivered to Bolivia.

Artillery

- Maxim-Nordenfelt 1″ machine gun;

- 20mm Oerlikon automatic gun;

- 2 mm Becker automatic gun;

- 47mm gun;

- 60mm Krupp mountain gun;

- 65mm Vickers Mk E gun;

- 75mm Schneider gun;

- 75mm Krupp L13 mountain gun;

- 75mm Vickers Mk KK gun;

- 81mm Brandt-Stokes mortar;

- 105mm Vickers Mk B mountain howitzer;

- 105mm Vickers Mk C howitzer.

Aviation

- Curtiss Hawk II;

- Curtiss Falcon;

- Vickers Type 143;

- 1 Junker 52, used primarily as ambulance aircraft;

- Ford trimotor.

The armament of Paraguay

Light weapons – when adopting modern rifles, both Bolivia and Paraguay choose small bore rifles shooting the same cartridge: the 7.65mm Mauser, which was extremely convenient when the two countries engaged in hostilities, because each one of the protagonist could use captured material of their adversary:

- Belgian M 1903 Browning pistol (9mm Browning long);

- Mannlicher M1905 Austrian pistol, similar to the Argentinean model (7.65mm Mannlicher);

- Finnish Suomi KP 31 submachine gun (9×19);

- M1907 Mauser rifle and carbine. Similar to German Mauser Gewehr 98, built by Mauser (7.75×53). The rifle has a straight bolt handle and a rear toboggan sight graduated up to 2,000 m, it mounts a bayonet. The carbine is provided with a bent bolt lever, a tangential rear sight graduated up to 1,400 m, with a hand-guard. The fore arm is prolonged to the mouth of the barrel. The weapon does not receive a bayonet;

- M1909 short rifle. Produced by Haënel in 7×57 with a G88 type bolt, a Mauser magazine and a stock with semi pistol grip and a hand guard;

- M1927 Mauser rifle and carbine. Made in Spain by the Oviedo Small Arms factory (7.75×53), with a straight bolt handle, a tangential rear sight graduated up to 2,000 m and a hand guard;

- Belgian Mauser FN 24/30 (7.75×53).

- Czech Mauser Vz 12/33 (7.75×53).

- M 1922 Mauser 1933 carbine and musketoon, German weapons manufactured by Mauser (7.75×53);

- Danish Madsen light machine gun (7.75×53);

- Vickers-Berthier light machine gun (7.75×53);

- German water cooled Maxim machine gun (7.75×53).

- British Vickers water cooled machine gun (7.75×53).

- American Colt-Browning MG38 water cooled machine gun (7.75×53), 144 examples between 1928 and 1934.

Artillery

Some old guns of various origins, supplemented by new Vickers guns and material taken from the enemy.

Vehicles

Paraguay used Chevrolet, Ford and International trucks. Some cars were equipped with machine guns. Italy provided Ansaldo L 3/33 caterpillars.

Aviation

The Paraguayan Air Force counted 21 aircraft at the beginning of the conflict, of which:

- 7 Potez 25, biplane, a two-seat French plane, used for reconnaissance and bombardment;

- 7 Wibault 73 C, single seat, monoplane fighter of entirely metal construction, with an aerofoil parasol wing;

- French Breguet 19;

- 5 Fiat CR 20;

- some Junker 50.

The Chaco War received little publicity outside of South America. In Europe few people heard of it, as it was a period where no TV, nor mobile radio set, nor I-phone existed; only a few articles were printed in the newspapers.

Without being like the Spanish Civil War: a vast field of experimentation for new materials, it was the first major conflict between the World Wars where machine pistols were used. It is also necessary to note the British Vickers company, which without any remorse, sold weaponry to both belligerents… as long as they could pay.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V17N3 (September 2013) |