By Kevin Dockery

There are few gun designers who can claim to have been as successful as John Browning. His weapons have stood the test of time and served the US Forces in one form or another since World War I. The .50 M2 Browning is still in front line service and looks like it will remain so for a number of years to come.

A drawback with the belt-fed Browning machine gun designs is that they were heavy. With the .50 being normally moved on board a vehicle, the weight problem isn’t a serious one. For the footsoldier who has to carry everything on his back, the weight of a Browning .30 caliber was very noticeable.

When the US entered World War II, it was armed with the Browning M1917A1 watercooled .30 and the M1919A4 aircooled version of basically the same weapon. The tripod-mounted M1919A4 could be handled and operated by one man without its tripod, but only just. Unmounted, the M1919A4 could be hip-fired during an assault. But that was an inaccurate and clumsy method of employing the weapon. And even a strong man couldn’t hold the gun up, aim, and fire an M1919A4 very effectively.

The German Army had fielded a new concept in machine guns for World War II, the general purpose gun. The MG 34 and later MG 42 were both reasonably lightweight guns that could be fired accurately from their built-in bipods by one man. The quick-change barrel system, especially the design used on the MG 42, allowed the weapon to have a good sustained fire capability from a tripod mount.

The real advantage of the general purpose machine gun concept was that it added greatly to the overall volume of fire that could be put out by a squad-sized unit. The US Army took note of this fact and closely examined captured specimens of the MG 42. The tests at Aberdeen Proving Ground in February 1943 impressed the US ordnance personnel attending them. The orders went out to produce two MG 42, chambered for the US .30 caliber service round.

The Saginaw Steering Gear Division of General Motors was contracted to produce two .30 caliber versions of the MG 42, the weapons to be designated the T24. In one of the truly amazing errors in US weapons design, the dimensional changes to convert the MG 42 to the T24 were mis-calculated. Several parts of the T24 were too short to operate with 30-06 ammunition. Even the receiver was too short by 1/2 inch.

The 10,000 round endurance tests of the T24 were discontinued after only 1,483 round had been fired – with 50 malfunctions. A redesign of the T24 would have been too costly in terms of time and material in a wartime environment. The project was canceled and the two existing specimens relegated to a museum.

The only “light” belt-fed machine gun issued to US forces during World War II was a modified Browning M1919A4. The addition of a buttstock, carrying handle, bipod, flashhider, and internal modifications of the Browning .30 resulted in the M1919A6 version. At over 32 pounds weight empty, the M1919A6 could be put into action by one man, but was light only in comparison to a tripod-mounted weapon. The M1919A6 was tactically more flexible with its attached bipod, but it still was not in the class of a general-purpose weapon.

The US military renewed its interest in a new light, general purpose machine gun after WWII had ended. Another German WWII design intrigued the US ordnance community enough to begin some experiments with it. The Krieghoff FG 42 had been developed for German paratroop forces and was a combination of innovative ideas of its own, and some adoptions of interesting ideas of earlier weapons.

Designed as a lightweight machine rifle, the FG 42 was primarily made of metal stampings and welding to ease production. Magazine fed from the left side by a horizontal 20-round magazine, the FG 42 was not capable of truly sustained fire.

The bolt and operating rod of the FG 42 was very similar to that used in the much earlier Lewis gun. The German designers had modified the system so that the FG 42 fired on closed bolt for accuracy in semiautomatic fire, but switched over to firing from an open bolt when set on full automatic. The open bolt system allowed the weapon to cool more efficiently during full-auto fire.

The late-model FG 42, called the FG 42 type II, weighed in at only 11.44 pounds empty. The addition of an effective muzzle break and the in-line design of the stock helped minimize muzzle climb, but the weapon’s light weight worked against it in full auto fire. Accuracy, when fired in semiautomatic, was considered excellent, and the weapon was quick and easy to handle and lay on target.

A late model FG 42 was taken directly by the US Ordnance Corps to be refined into a belt-fed weapon. Bridge Tool and Die Works of Philadelphia was given the contract to produce the new weapon, designated the T44. A standard late model FG 42 was modified to accept the belt feed mechanism from the MG 42 on the left side of the weapon.

The orientation of the feed mechanism of the T44 allowed for minor changes in the basic design of the FG 42, but gave the weapon unique loading characteristics. The non-disintegrating German link belt would feed in from the lower left side of the T44, directly above the pistol grip. The empty link belt came out of the top of the weapon, falling down on the right side. Being that the T44 remained chambered for the German 7.92x57mm round, eliminating the problems that plagued the T24 project, the weapon was considered only a test bed to try out the feasibility of the design.

By December, 1946, the mechanical conversion of the basic FG 42 into the T44 prototype had been completed. Test firings proved much of what the German paratroops had found during the war, that the overall design was too light for sustained full automatic fire. The relatively light barrel of the FG 42 would overheat quickly, especially with the larger ammunition capacity given with the belt feed of the T44 conversion. In addition, the light weight of the weapon caused excessive spread of the rounds in a fired burst. But mechanically, the design had merit and a new contract was issued for further development.

The T44 itself never went beyond the prototype stage. But the basic bolt and operating rod mechanism of the FG 42 and the belt feed system of the MG 42 were incorporated into a new design.

Initiated in April 1947, the new weapon was designated the T52. Using much the same configuration as the original FG 42, the T52 had the feed mechanism placed on top of the receiver in the usual position, feeding from the left side of the weapon. In addition, the T52 had the wooden forearm and buttstock, bipod, muzzle brake, and trigger group of the FG 42. The barrel could not be removed from the weapon and the bolt locked into lugs in the receiver.

Later models of the T52, the T52E1 and E2, incorporated additional changes indicated by testing. The locking lugs of the bolt now engaged recesses on a barrel extension, allowing a quick-change barrel to be used to keep the weapon from overheating. The fixed headspace on the later designs eliminated the time needed to adjust headspace when a barrel was changed, as on the earlier Browning designs. Both light and heavy barrels were tried out, weighing 4.5 and 7 pounds each respectively.

The gas system was changed to that of the gas-expansion-cutoff design. In the gas-expansion-cutoff system, the propellant gas is ported from the barrel directly into the gas piston sitting in the gas cylinder. The gas piston has a solid end, bearing on the operating rod, and a hollow body with the other end open. Expending gas moves through ports into the body of the gas piston, driving it back against the operating rod. When the piston has moved a short distance, the gas supply is cut off when the ports on the piston move away from the single gas port between the barrel and the gas cylinder. Excess gas pressure is then bled away though the barrel and a small bleed hole in the front of the gas cylinder.

This complicated system gives a constant push of sufficient force to operate the action while preventing excess pressure from putting wear on the moving parts. Theoretically, the piston will allow enough gas to operate the action, more when the action is dirty or sluggish. This gas cutoff system gives a smooth, even operating force on the action rather than the single sharp jolt of a standard gas piston.

The Army Equipment Development Guide dated 29 December, 1950 stated that a new lightweight general purpose machine gun should be developed to replace all of the .30 caliber weapons (the M1917A1, M1919A4, and M1919A6) then in service. The new weapon was to have an effective range of 2,000 yards, a maximum weight of 18 pounds, a quick change barrel with a flash hider, use a disintegrating link belt, and have a cyclic rate of 600 rounds per minute. In April 1951, a second series of weapons were begun, the T161 family, to meet the new requirements and accelerate the overall program to develop a new machine gun.

The T161 design was to be chambered for the standard .30 caliber M2 round, in case the developing T65 Light Rifle round did not meet requirements. The T52 series had been chambered for the different types of T65 round as it was being developed. The new T161 weapon was modeled after the T52 series but developed with improved mass production techniques incorporated into it. In addition, the T161 series had the actuator lug for the belt feed mechanism on the bolt rather than on the rear of the operating rod as used in the T52 series. This change in the method of operating the feed system was one of the major differences between the T52 and T161 series.

The T161E1 was the first of the new series to see firing tests, now designed to accept the T65 lightweight rifle round. By March 1953, the T161E1 was ready for firing and underwent testing against the T52E3.

In early 1953, the best features of the T52 series had been incorporated into the T52E3. The lightweight barrel had been abandoned due to the heavy barrel giving greater stability for automatic fire and having to be changed less often for sustained fire. The wooden furniture of the earlier designs had been changed to stamped metal for the buttstock and forearm. Overall, the T52E3 weighed 23.58 pounds empty, had a 22-inch barrel, and an overall length of 43.5 inches. This was a savings of over eight pounds from the M1919A6 in a weapon over 9 inches shorter.

Drawbacks found in testing the T52E3 were that the weapon had a greater number of parts than earlier designs, was not a durable, and didn’t function as reliably. The T52E4 model corrected some of the deficiencies found in the earlier weapon, with different parts used to ease its manufacture. In May 1954, a contract was issued to build the T52E5, which was to incorporate all of the best features of the earlier designs.

By August 1954, the T65 ammunition family had been officially adopted as the new NATO standard round. Both the T52 and T161 series now were chambered for the new ammunition. To feed the round into the belt fed weapons, a new disintegrating link had been designed that allowed the round to be pushed forward, stripping it out of the link. As the ammunition left the belt, the individual stamped metal links separated and fell away from the feed mechanism.

The links used in the 1950s tests, the T55 link, was heavier and less flexible than desired for use. The T89 disintegrating belt link was lighter in construction, held the round firmly with a detent tab locating on the extractor groove, and made a more flexible belt. The T89 link later became the standard issue M13 belt link.

Tests on the T161E1 indicated that it needed additional changes to get the design ready for the more rugged Army user tests. The barrel assembly was redesigned, eliminating an aluminum component that deformed from the heat of firing. The feed plate was modified for smoother loading of the ammunition belt. A carrying handle was added to the weapon and the rear sight changed to one that was adjustable for range (elevation) only. The modified weapon was designated the T161E2 with 20 specimens ready for testing by the Army Field Forces (AFF) Board No. 3 in July 1953.

The AFF Board decided that the T161E2 was unsuitable for issue, citing failures to fire and stoppages due to the gas system and other faults. The 3-pound lightweight barrel was also abandoned at this point. The front sight on the both the heavy and light barrels were considered too weak for field use, having bent during testing. In spite of the drawbacks, the AFF Board stated the design showed sufficient promise to warrant further considerations.

Additional modifications to meet the AFF Boards recommendations were made on the 20 T161E2 test guns, resulting in the T161E3 design. The feed mechanism was modified to operate with the new T89 links. Additional changes were made in the firing pin. buffer assembly, and operating rod and some other minor parts. Besides the 20 modified T161E2 weapons, an additional 100 T161E3s were produced for testing.

Extensive testing of the T161E3 included temperate and arctic environments, were the T161E3 was well liked by the soldiers operating it. New tripod mounts for the T161E3 did not do as well in testing and modifications were recommended. Testing also demonstrated that the T161E3 did not have the durability of the earlier Browning designs, but did meet many of its design parameters.

The testing board reported its results on 31 July 1956. The T161E3 was found to be superior to the M1917A1, M1919A4 and M1919A6 in simplicity, portability, reliability under adverse conditions, barrel life, and other factors. The T161E3 was found to be very easy to use in hip and shoulder firing, a point stated by the majority of the gunners in the tests. The operators also preferred the new weapons because they were lighter, shorter, and easier to disassemble and assemble for cleaning.

In August 1956, the CONARC (Continental Army Command) Board No. 3 (now the US Army Infantry Board) overlooking the T161E3 tests recommended the T161E3 for adoption. Minor deficiencies in the weapon and mount would be eliminated during production. The T161E3 gun was designated the M60 machine gun and the T89 belt link designated the M13 metallic belt cartridge link, both for standard issue, on 30 January 1957. At that time, the M1917A1, M1919A4, and M1919A6 Browning machine guns were designated as limited standard. (Dan’s note: There are some registered transferable T161s in private hands, and these should be on the C&R list if they are not already.)

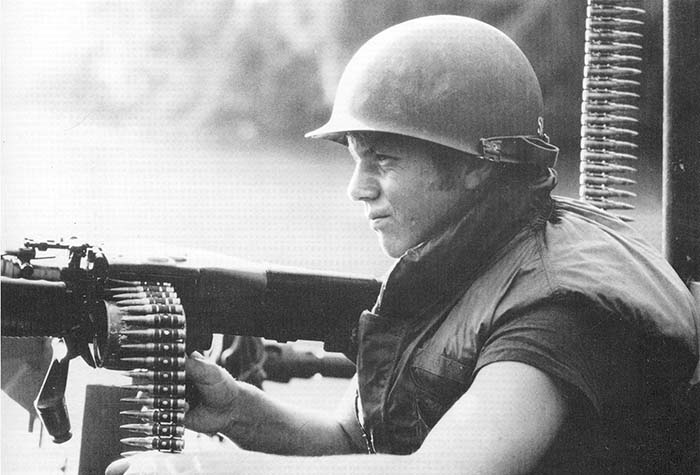

When the US Marines first landed in Vietnam on 8 March, 1965, their unit machine guns were still a mix of Brownings and M60s. The Browning guns remained either on vehicles, or tripod mounted along a base’s perimeter. The M60s were the machine guns of choice for patrols. Readily handled by one man, the M60 was assigned a crew of two, the gunner and assistant. These two men carried the weapon, equipment, and ammunition to keep the M60 in operation.

The M60 could be fired from the prone position, supported from its attached bipod. Or a gunner could stand and fire the weapon from the hip, under the arm, or even from the shoulder like a large rifle. This tactical flexibility of the M60 made it very popular among the men who carried it, and those it helped support.

As with any belt-fed weapon in a small military unit, ammunition was never in great enough supply – at least not according to the men in combat. A 100-round belt for the M60 came packaged in a cardboard box, the box held in a cloth bandoleer. The bandoleer could be inserted into the attached magazine pouches of early M60s, or hung from the belt feed trays of the later models (post 1966). The attached cloth strap on the bandoleer also allowed it to be slung from the shoulder for carrying.

Most soldiers found it convenient to just clip the loose ends of a 100 round M60 belt together and make the belt a closed loop. The loop of ammunition could be slung over the shoulders and across the back and chest for easy carrying. This technique evenly distributed the weight of extra ammunition across the shoulders. But it also exposed the ammunition belts to all the dirt, mud, and crap of a Southeast Asian jungle.

But when kept reasonably clean and lubricated, the M60 worked, and it worked very well. The machine gun could be carried through the jungle on a patrol ready for action. The heavy 7.62mm slugs from an M60 could chop down trees and rip an enemy formation to shreds.

Set up on a tripod with a well-trained crew and spare barrels, the M60 could put out a sustained stream of fire. Changing barrels every ten minutes, an M60 could put out 100 rounds per minute for extended lengths of time. They defended outposts, river boats, fire bases, and squads with equal efficiency.

Force multiplier is a term used in the US military for, among other things, new weapons used to increase a combat unit’s effectiveness against the enemy while not increasing the size of the unit. This can mean weapons that increase the volume of fire that can be effectively put out by a limited number of men.

The M60 quickly became the major force multiplier for small units in Vietnam. Whether straightforward infantry outfits, Marine units, special units, boats, aircraft, or vehicles, the M60 could be found putting out its fire

“Humping the pig” was a derogatory term for carrying the M60. The Pig was heavy and had a voracious appetite for equally heavy ammunition. There was nothing practical that could be done about the weight of ammunition for the M60. But for special units, there was a lot that could be done to lighten the weapon. For these forces, the LRRPS, SEALs, Force Recon, and Special Forces among others, weight carried on patrols was measured in pounds and ounces. Anything that could be lightened, was.

The first thing to go to lighten the M60 was the bipod. By just unscrewing the flash hider, the bipod could be dismounted from the barrel and 2.5 pounds removed. On some guns, the barrel was cut back to the gas piston and rethreaded to take the flash hider. The front sight would be missing from such a shortened barrel, so the rear sight could be removed. Without sights, the gun was pointed instinctively rather than aimed. Buttstocks were removed and the receiver cap on an M60C installed in its place. Later in the war, special rubber boots were made that replaced the buttstock assembly for special units such as the SEALs.

The “chopped” or cut-down M60 was a bullet hose – and a very effective one. During an ambush at close ranges of 30 meters or less, the firepower of such a weapon was devastating. And it was easy to carry, especially so for a big, fit, man. One SEAL, a group known to be fit, carried his M60 along with up to 1,200 round of ammunition, or more, depending on the mission. The modified M60 was no longer a crew-served weapon, more of a very large individual one.

The M60 did have several drawbacks in its design. The stamped metal receiver could be damaged more easily than the Browning machine metal receivers. Looseness that could develop between the sheet metal receiver and the trunnion block was corrected with a modification that had additional welding reinforce the joint.

When the M60 was stripped for cleaning, the gas piston could be installed backwards. This error usually wasn’t discovered until someone tried to fire the weapon and only one round went off. The feed cover mechanism could be damaged if it was closed on a bolt that was in the forward (fired) position. And other small parts could be mis-assembled that would result in an eventual weapons malfunction.

But these problems could be reduced through training. A primary flaw that was never addressed was that the weapon wore out bolt assemblies fairly quickly. This wear problem was directly attributed to the fixed headspace, quick-change barrel system used on the weapon. Maintenance manuals required that burrs building up on the bolt surfaces from this excessive wear be stoned down and smoothed by unit armorers. This technique was little more than a temporary fix and actually increased the rate of wear for the bolt. Experienced gunners had spare bolts available to replace those that started to show burrs building up.

The extra weight of the bipod and gas system on the spare barrel of an M60 could have been reduced if these parts had been mounted on the receiver instead. A handle on the barrel would have made changing a hot barrel much easier, and not one that required a heavy asbestos mitt to be carried by the assistant gunner.

But these problems did not keep the M60 from becoming the most widely used machine gun by US forces during the Vietnam War. The weapon and its variants remained in US service into the 1990s, exceeding the US service life of the Browning M1919A4.

Field modifications to the M60 were seen throughout Vietnam. Empty c-ration cans were attached to M60s that fed from extra-long belts. This very simple modification helped straighten out the belt before it fed into the weapon. Electrically triggered M60C models were seen on helicopter gunships – two guns mounted outboard of the rocket pods on each side of a Huey gunship. The later M60D had spade grips instead of a buttstock for easier use from a fixed mount – such as a helicopter door gun.

Cursed by some, loved by some, the M60 machine gun became a symbol of the US Serviceman in Vietnam.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V5N7 (April 2002) |