By Frank Iannamico

Despite Its High Cost, Millions Were Made for the U.S. and the Allies in WWII

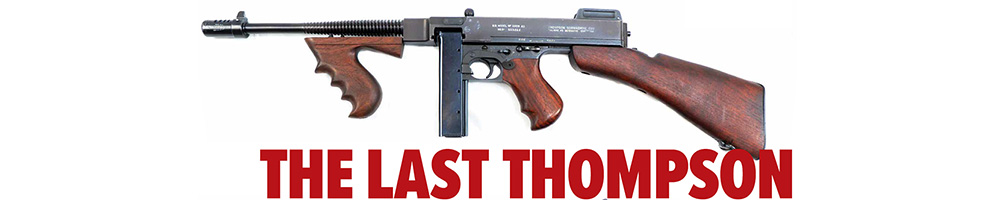

The Thompson submachine gun was conceived by U.S. Army General John Thompson as a weapon to assault and clear out enemy trenches during World War I. Thompson formed the Auto-Ordnance Corporation to develop his submachine gun. World War I ended before the weapon went into production. After the post-war design was finalized, Auto-Ordnance, which had no facilities for mass production, subcontracted with Colt to manufacture the Thompson submachine gun. A total of 15,000 Thompson submachine guns were produced by Colt from 1921 to 1922. Sales were very disappointing; for all intents and purposes the concept was a failure though criminals of the day recognized the Thompson’s value. Police departments began to purchase Thompsons just so they would not be outgunned by gangsters. Many gangland shootings made the headlines in all the newspapers; the Thompson submachine gun was getting a very tainted reputation.

By early 1939 when it appeared World War II was imminent, the Thompson submachine gun was nearly 20 years old. An entrepreneur by the name of Russell Maguire sensed that there would be a need for weapons when war came. Through some dubious tactics, Mr. Maguire was able to gain controlling interest in the floundering Auto-Ordnance Corporation.

World War II was a more fluid conflict than World War I had been. It would be a war where the submachine gun would play a significant role. Despite the design being over 20 years old, it was the only proven weapon that could be fielded quickly. However, once again Auto-Ordnance had no manufacturing capabilities. A forward-thinking Russell Maguire contracted with the Savage Arms Company to manufacture the Thompson for Auto-Ordnance. The first Thompsons made by Savage were similar to those made by Colt. Savage delivered the first completed guns to Auto-Ordnance in April 1940. Savage also manufactured many parts to supply Auto-Ordnance’s own factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that began manufacturing the M1928A1 model in August 1941.

The British Army, despite their resistance to what they referred to as “gangster guns,” was one of the first customers to order Thompsons. At this point, the United States had not yet entered the war. The United States was forced to enter World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The U.S. Army began quickly growing, and weapons were needed to arm soldiers and Marines.

The U.S. government had on several occasions voiced concern over the .45 caliber submachine gun’s high price, which was costing the government the same as a Browning belt-fed machine gun. Savage and Auto-Ordnance were both aware that the Ordnance Department was seeking a less expensive submachine gun to replace the Thompson.

In November 1941, the engineering staff at Savage began conducting a study of how the M1928A1 model Thompson could be simplified. The engineers were looking for ways to decrease cost and increase production. Consuming much of the manufacturing effort was the receiver, more specifically, the rails inside of the receiver that the bronze Blish lock traveled on. The three-piece bolt/lock/actuator of the 1928 model was also labor intensive to manufacture. The engineers at Savage doubted that the locking device was necessary.

A Less Complex Submachine Gun

In late February 1942, a “simplified” prototype Thompson submachine gun conceived by Savage was ready to be submitted to the Ordnance Department for testing. The bolt assembly was a very simple rectangular block of steel. This allowed the receiver to be redesigned for easier manufacture and its width reduced. The inside of the receiver simply had a rectangular channel milled into it to accommodate the bolt. The bolt had been redesigned with two sear notches. This allowed the weapon’s safety lever to be engaged when the bolt was in the forward position on an empty chamber. Since drum-type magazines had proven unsuitable for military use, the new receivers eliminated the lateral slots on the sides of the magazine well for accommodating them.

Savage shipped the new weapon to Russell Maguire at the Auto-Ordnance Corporation headquarters. The Savage Corporation told Auto-Ordnance that it was submitting the redesigned Thompson, “Without any claims for compensation, reimbursement, royalty or patent interest.” The Auto-Ordnance engineering staff examined the new design and then submitted it to the Ordnance Department in March 1942. The new Thompson was sent to Aberdeen Proving Ground for testing and evaluation. After a few government recommended alterations to the prototype were made, the new Thompson was recommended for adoption as “Submachine Gun, Caliber .45 M1” on March 24, 1942.

The pilot rod for the recoil spring was simplified for easier manufacture and was held in place by a new type buffer. The M1’s pilot rod was made longer than those for the 1928 design to completely contain the spring. The M1’s pilot rod and buffer lessened the possibility of damaging the recoil spring during assembly and disassembly; a problem often encountered with the 1928 models.

The M1 featured a smooth barrel without the radial cooling fins or a threaded muzzle for a compensator. The rear sight installed on early production M1 Thompsons was the same simple unprotected “L” type. This design proved to be easily damaged and was replaced by a similar sight but with protective side “ears.”

By July 1942, Savage began delivery of the first new Thompson model, now designated as the M1 Submachine Gun. The Auto-Ordnance Bridgeport and Savage Arms factories both began production of the Thompson M1 model in July 1942. However, due to many technical problems experienced by the Bridgeport factory with the change over from the M1928A1 model, the actual manufacture of their M1s was delayed by several months.

While in July 1942, Savage had turned out 48,000 guns, Auto-Ordnance was struggling to meet its scheduled production mark. Contributing to the production delays were problems in deliveries of materials, equipment and tooling authorized by the government for M1 production.

After the M1 production finally commenced at Auto-Ordnance’s Bridgeport plant, more problems were encountered. The Springfield Ordnance District refused to accept any of the Auto-Ordnance Bridgeport-manufactured M1s because of the increase in their full-auto cyclic rate over the M1928A1 model. Officials from Washington, the district ordnance office and Auto-Ordnance engineers conducted studies and tests, all failing to provide a correction for the condition. Finally, on December 9, 1942, official notice from the Ordnance Department in Washington gave the district permission to waive the rate-of-fire requirement and accept the Bridgeport M1 guns. In the interim, the M1 Thompsons being produced at Savage were being accepted in large quantities by the Rochester Ordnance District without any problems.

The M1A1 Model

The Savage Arms Company continued attempts to further simplify the design by experimenting with a fixed firing pin model. The prototype was originally fitted with an M1 type bolt with a firing pin fixed in an extended or “in battery” position. The firing pin, spring, hammer and hammer pin were omitted. Later the “fixed” separate firing pin was eliminated and replaced by a fixed “firing pin” machined onto the bolt face.

The Springfield Ordnance District was notified that manufacture of a fixed firing pin bolt for use in the M1 submachine gun was authorized. In order to distinguish between submachine guns equipped with separate firing pins and fixed firing pins, the submachine guns fitted with the fixed firing pin would be designated as “Gun, Submachine, Caliber .45, Thompson M1A1” (A1= Alteration 1).

By the time the Springfield Ordnance District began accepting the M1s made at the Bridgeport plant, the new Thompson M1A1 model had replaced the M1. Most of Auto-Ordnance M1 Thompsons were then upgraded to the M1A1 configuration and the A1 designation added by hand stamping “A1” on the receiver.

On earlier models, the forward motion of the bolt was stopped by the front of the bolt cavity in the receiver, a major factor in determining the length of the chamber. To increase reliability the cylindrical protrusion at the front of the M1A1 bolt was increased by .028-inch. With the longer front shank, the bolt’s forward motion was stopped by the cartridge seated in the barrel’s chamber unless the chamber was empty. The redesign ensured that the fixed firing pin would strike the primer with greater force, reducing misfires. However, the downside to the fixed firing pin design was that it increased the chance of an out of battery discharge of a cartridge.

The cost for Savage to manufacture an M1 was $23.44. On February 24, 1942, Savage agreed to a contract to manufacture the M1 model for Auto-Ordnance at the cost of $36.37 per unit, providing Savage with a profit of $12.93 per gun. Auto-Ordnance then charged the U.S. government $43.00 for an M1 model and $42.94 for the M1A1 version, although the prices and profits varied slightly from contract to contract.

Serial Numbers

Unlike the 1928 Thompsons, the manufacturer’s initials, “AO” or “S,” were not used as a serial number prefix on the M1 series. To identify who made a particular M1 or M1A1 Thompson, the manufacturer stamped their code letters on the bottom of the receiver where the front grip mount is fitted. The letters used were “S,” which indicated Savage manufacture, or “A.O.C.” for weapons made at the Auto-Ordnance Bridgeport plant. As on the previous M1928A1 model, the Auto-Ordnance Corporation name and Bridgeport address are present on the receiver’s right side, regardless of who manufactured the weapon. Another change noted in the M1/M1A1 Thompson was the spelling of the word “caliber” on the receiver. The word was changed from the early spelling of “CALIBRE” to the U.S.-recognized spelling, “CALIBER.”

Savage-manufactured M1 and M1A1s were stamped with the Army Inspector of Ordnance’s initials of the Rochester, NY, Ordnance District. AIOs of the Rochester District were Lt. Colonel Ray L. Bowlin, using stamp “RLB,” and Colonel Frank J. Atwood, using stamp “FJA.” The Bowlin RLB marking is found only on the early M1 Thompsons. All Savage M1 and M1A1 submachine gun receivers and frames were also marked with the encircled “GEG” acceptance stamp of Auto-Ordnance’s civilian inspector at Savage’s factory, George E. Goll.

M1 and M1A1 Thompsons produced at the Auto-Ordnance plant in Bridgeport, Connecticut, would have the acceptance stamp of the Army Inspector of Ordnance of the Springfield District. Very early M1s would be marked with the stamp “WB”—Colonel Waldemar Broberg. Later production would be marked with the “GHD” stamp—Colonel Guy H. Drewery.

There have been many M1A1 trigger frames documented that do not have serial numbers. During repairs and rebuilds, the frames and receivers were often mismatched. This caused a lot of confusion when the weapons were stored in racks, and the frame number was mistakenly recorded instead of the receiver serial number. U.S. Ordnance specification AXS-725, dated January 7, 1943, called for a serial number to be marked, “Only on the receiver.” Subsequently, M1A1 frames manufactured after that date had no serial numbers applied. Arsenals were instructed to obliterate or remove serial numbers from the frames of the M1/M1A1 Thompsons. Due to the depth of the markings, the practice was soon discontinued.

M1’s and M1A1’s Final Days

In January 1943, the Ordnance Department announced to the Auto-Ordnance Corporation that the Thompson was going to be replaced by the newly developed U.S. M3 submachine gun. After the Ordnance Department’s official adoption of the M3 submachine gun, Thompson production was scheduled to be concluded in July 1943. Plans were made to begin tapering off production of the weapon. In April 1943, 62,948 M1A1 guns were manufactured; this was reduced to 55,000 in May and 51,667 in June. This left only 5,000 guns remaining to be manufactured in July 1943 from existing contracts. Authority was then received from the Ordnance Department in June to procure an additional 60,000 weapons by the end of August. Before the end of August, more orders for the Thompson gun were received from Washington. A total of approximately 119,091 additional Thompson M1A1 models were to be manufactured, providing continuance of production through December 1943. At the end of December, there were enough parts remaining to assemble approximately 4,500 additional guns. In January 1944 authorization was granted to complete the remaining guns by February 15, 1944. Production briefly resumed in February, completing a total of 4,092 additional guns. On February 15, 1944, the very last M1A1 Thompson submachine gun was accepted by the government via contract W-478-ORD-1949.

The Savage Arms Corporation manufactured an estimated total of 464,800 M1 and M1A1 model Thompsons, while the Auto-Ordnance Bridgeport plant turned out an estimated 249,555 M1s and M1A1s. A presentation-grade M1A1 Thompson was made by Savage. The serial number represented the total number of 1928 and M1/M1A1 Thompson submachine guns made by Savage: 1,244,194 from April 1940 until February 15, 1944. The number does not include the Thompsons made by Auto-Ordnance’s Bridgeport factory.

••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Article excerpted from the book American Thunder III, available from Chipotle Publishing LLC.

Special thanks to Curator Alex MacKenzie and the entire staff at the Springfield Armory National Historic Site.

Springfield Armory National Historic Site

Springfield, MA

413-271-3976

www.nps.gov/spar

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V23N2 (February 2019) |