By Frank Iannamico

The surplus business was growing and things began to get really interesting. There were two primary players in those early days. One was an Englishman named Peter Anniston. The other was French-born Jacques Michault. These fellows, largely isolated from the U.S. market, were based in Europe and had started to deal in surplus military armament.

This was Europe in the early 1950s. There were all sorts of nationalist movements throughout the northern tier of Africa, and the demand for firearms in this and other regions was insatiable. Anniston and Michault were able to buy military bolt-action guns, semiautomatic rifles, machine guns, all the incredible array of surplus Allied and Axis weaponry left over in Europe from World War II. It was really very little problem for them to find all the supply they needed.

At the same time Anniston and Michault were doing these transactions, they were finding that a lot of the weaponry available to them was obsolete and did not have current military application. They turned to American gun dealers for disposal of this excess inventory. The first item Golden State was offered was a large lot of Swiss Schmidt-Rubin Model 1911 long rifles in 7.5mm caliber. They really didn’t know what to do with the offer. As expert as they had been in selling off a batch of ten of any one rifle, or perhaps even fifty, but the idea of being offered and having to dispose of 5,000 rifles at a time was at first staggering to them.

They had to try and figure out a time frame that it would take to sell the rifles. There were also legal and importation restrictions, and the proper licensing questions. Both Retting and Brenner were inexperienced in this type of trade and had to carefully feel their way through the transactions learning as they went. They ventured timorously into contact with the U.S. State Department to obtain the import licenses and permits handled by them. They needn’t have feared; the authorities were as inexperienced as they were, hardly knowing what they were doing either, since up until that time there had been very few civilian imports of large quantities of weapons.

They pressed forward and found themselves actually going forward with the importation of the first 5,000 Swiss rifles. They paid $3.50 apiece for them, and each rifle came with 100 rounds of ammunition, as well as a bayonet and scabbard. The rifles were in magnificent condition.

As the Schmidt-Rubin rifles came in, they learned about customs duties and federal excise taxes and so forth. They established costs and set a sales price. The rifles were tagged at $15.95 each, with 100 rounds of ammo thrown in. Their modest shop located on Washington Boulevard in Culver City, California had a small showroom that measured 10-feet by 12-feet, and they were used to having one or two people in there at a time. But when the Swiss rifles arrived, they started to get line-ups of 30 and 40 and 50 customers at once, waiting impatiently in line outside the shop. The value of these previously unobtainable and high-quality guns at that price was remarkable, and the gun aficionados immediately recognized it.

The Schmidt-Rubin rifles sold amazingly well. After all, they were offering a practically new rifle, Swiss quality, all parts with matching numbers, beautiful woodwork, with a bayonet and 100 rounds of what came to be very scarce ammo for way less than $20. Even by the monetary standards of the 1950s, the rifles were quite a bargain.

This first large-scale experiment with surplus weaponry was exhilarating as they finally realized the tremendous potential before them. The first tenuous steps into the world of surplus arms had been taken, and it was all straight ahead from there.

As time went by they became aware of other firms in the Los Angeles area who were also delving into overseas surplus material. One of these firms, Western Arms Co., was a supposed importer of material from Central and South America. They had a huge inventory of Rolling Blocks, Caliber 7mm and 11mm.

Another company dealing in surplus arms in Los Angeles was run by a man named Hy Hunter. He had a large inventory of European pistols and again over a period of time, Retting and Brenner bought hundreds of items from him for resale in their store.

Other competition was from a California firm situated on Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena. The establishment, called the Pasadena Firearms Company, was owned and operated by Al Gettler along with a junior partner Seymour Ziebert. The company had established some important connections in Mexico and was able to import some unique firearms from that country, like brand new Mexican Mauser military rifles straight from the factory, somehow bypassing the government depots the guns were originally destined for. The Mausers were beautiful in the straight 1898 configuration with a 29.5-inch barrel and the eagle and rattlesnake crest on the receiver ring. The rifles were chambered for the favored Latin American 7x57mm Mauser round. The Mexican Mauser deal eventually became quite a scandalous affair resulting in many high ranking Mexican Army officers retiring early, while lesser heads rolled.

Of all the surplus dealers established in California it seemed as though Al Gettler and Seymour Ziebert of the Pasadena Firearms Company were the one that had their act together.

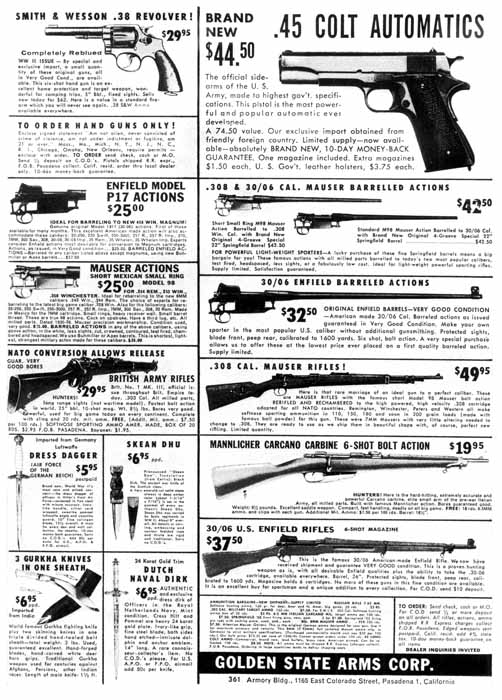

Golden State Arms

Pasadena Firearms Company was an innovator in the surplus field, and it captured the attention of Brenner and Retting. After many meetings and phone conversations, the concept of the four men putting their labor, finances, and mutual knowledge together and perhaps coming up with a bigger, better company – one that could really pursue these deals overseas and go for it in a big way. Eventually, a new entity called Golden State Arms Corporation was formed. For many years the company was the kingpin importer and distributor of surplus arms in the United States.

An old mansion on Green Street in Pasadena was to be Golden State’s headquarters. The great house was of enormous size, and provided sufficient space for elaborate offices, a very large warehouse, and a major retail store. The retail store, in its heyday, was the largest gun store in the country.

The Golden State Arms retail store was sensational in its stock of antique material, both in terms of variety and of massive quantities. Swords, flintlocks, percussion guns from the Martin Retting side of the business, and more modern surplus weaponry from the old Pasadena Firearms Company stock, were supplemented by regular procurements of additional surplus weaponry from Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. The inventory of Golden State Arms was without peer in the glory days of arms collecting represented by the 1950s.

Brenner was made an executive vice-president of the company. His primary duties were to connect with selling parties overseas, private agents who would represent the company through their houses that existed in Europe and elsewhere. Brenner began to send letters to various governments and police departments throughout the world advising them that they were interested in purchasing any or all of their surplus weapons and ammunition. Soon there were offers coming in from all over the world.

A Cave in Denmark

During one of Brenner’s first buying trips overseas, a deal was made for the purchase of a few thousand miscellaneous handguns that were in the hands of the Copenhagen police. Europe was over-loaded with military surplus material. So when fresh-faced Americans showed up with lots of green dollars and said they actually wanted to buy all this surplus material, the Europeans were delighted. The Danes were no different; they just couldn’t get over it. The Copenhagen Chief of Police marveled at the fact that Brenner would buy this old stuff.

While dealing with the Copenhagen police, Brenner was also negotiating with the Danish army. The army, like the police, had a store of weapons that fell into two categories. First, there was equipment from pre-war Denmark that the occupying Germans couldn’t use and therefore did not confiscate. They just left undisturbed the local arsenals filled with Danish Krag rifles in 8mm Danish caliber; because this round was not interchangeable with the 8x57mm ammunition of the 1898 Mausers. The Danish service weapon was of no use to the Germans.

There were thousands of regular Krags in the warehouse, as well as substantial quantities of sniping and long-range target rifles that were used in military competitive shoots before the war – perhaps 500 of these. The target guns were fascinating and varied, with elaborate metallic sights and scopes. They were definitely collector items.

The next discovery was a sizable inventory of Nazi weapons, which had been stored by the Germans. The story went that, in the last days of the war, the Germans had planned for its troop of irregulars (known as “The Werewolves”) to fall back to Denmark and continue the battle from there with this warehoused material.

To inspect this find, Brenner and his boss Zeibert were taken to Jutland, on the northern peninsula of Denmark by two Danish officers. The officers led them to a depot, the greater part of which was underground in caves bored into the sides of hills surrounding the entrance. The cave floors had track laid so that the stored goods could be readily shuttled in and out by train.

From the depths of the caves, trains brought forth German MG34s and MG42s, new in the crates, with all the loading equipment, spare barrels, and spare parts kits: there were thousands of them. There were also German 98K Mausers, again in the thousands, and again brand new. This was rare; many collectors in this country had never seen a new, unfired German Mauser, but here they had them stacked up by the thousands.

Unfortunately, while these guns were available, the Danes were asking contemporary military pricing, which was not enough of a bargain for Brenner to make money on the deal. As an example, an MG42 machine gun would have cost $400 or so, and they weren’t really something saleable in the U.S. Surplus market. Later it was discovered that all of the material was eventually purchased and disappeared into the Middle East, a ready market for surplus military arms.

The Danish Army had been given the full American treatment. They had been given Garands, BARs, .30 and .50 caliber machine guns, and were quite content to retain those arms at that time.

From Denmark Brenner went down to Belgium where he met with Jacques Michault, the international arms trader. Jacques had set up a company whose acronym was SIDEM, which dealt weapons throughout North Africa, the Middle East, and the Far East. SIDEM still had more quantity of surplus than it knew what to do with, for the revolutionaries preferred not to have the bolt-action guns with which SIDEM was awash. There were rare exceptions; there was still a world market for British .303 rifles, although 1903 Springfields were strictly no sale with contemporary guerillas and insurgents.

SIDEM, had access to a lot of 50,000 1903 Springfield rifles, which Brenner was interested in. They were represented as new, but later it turned out that they were renovated rifles, which had left the U.S. years ago in fully serviceable, ready-to-go condition. Their location was very hush-hush; it was ultimately discovered that they were warehoused in Italy. They had been supplied to the government, which had booted Mussolini out. The Italians had switched sides from the Axis to the Allies. This enlightened decision by the always flexible and reasonable Italians led someone in America to think it would be a good idea to send over this batch of Springfield rifles. A cargo ship was dispatched from the U.S., which unloaded half of the rifles in Italy and the other half was sent to Greece.

It took a year before the deal was locked. The Springfield’s were very handsome rifles and much desired In the States. This was accomplished in the days before the U.S. government attempted to ban importation of guns, which were originally American issue and had been supplied to friendly foreign nations.

Police Guns

Golden State Arms continued corresponding with police departments. Within a short period, they were receiving offers from places as far away as Australia and South Africa. A police department in New South Wales, Australia claimed to have a large quantity of Smith & Wesson single action revolvers. The revolvers turned out to be nickel-plated American models with a shoulder stock and special leather holsters for both pistol and stock, all designed to be hung on a saddle. Golden State purchased the entire lot of 500 offered, and they were in excellent condition, at a price of $100 for the entire rig. Collectors quickly snapped them up.

Many U.S. police departments, instead of divesting their own obsolescent service weaponry, offered Golden State small to large lots of confiscated arms. Brenner bought random assortments in lots as large as a thousand.

Brenner began expanding Golden States’ chain of in-country agents throughout South America, Southeast Asia, and Europe maintaining correspondence with several dozen agents at a time. The contact would begin with exploratory letters, and then progress to agreeing on commissions and forming contracts with the agents. Then, the agent would pursue his police or military contacts to ascertain the availability of material. Next, there was a description of the merchandise as to character, quality, and quantity. Brenner typically followed up by traveling to the country in question and viewing the items, examining them for condition, rarity and completeness. The next step was the ancient and timeless process of negotiation, haggling either through the agent or directly with the selling party. Once a deal was struck, the agent arranged for packaging and shipping the purchase. Transporting the goods was a special problem; for they all had to be crated, crates loaded on pallets, and pallets loaded aboard ship. In some cases, upwards of 100,000 arms at a time had to be securely crated in wood.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V12N6 (March 2009) |