By Al Paulson

Suppressed rifles can be very useful tools for solving a variety of tactical problems. When used for law-enforcement applications, suppressed rifles offer the added benefit of reducing the likelihood of collateral public-relations and media-relations problems generated by the use of lethal force. Suppressed rifles are also valuable for discrete animal control, whether dealing with feral dogs attacking livestock or troublesome deer endangering aircraft at an airport. Not every department or agency can afford approximately $7,000 for an Accuracy International AW Sniper Rifle with AWC Thundertrap suppressor and Schmidt and Bender telescopic sight, or about $4,000 for a Gemtech Sniper Rifle with SPEC-OP 3 suppressor and Leupold Mark 4 scope. It turns out that the Savage Model 110FP “Tactical Rifle” with Sound Technology’s Dark Star sound suppressor and Choate’s Ultimate Sniper Stock together form a suppressed rifle system that provides excellent performance at a budget price of about $1,000 without optics. That’s about the cost of an AWC Thundertrap suppressor alone. The following discussion will evaluate the Savage rifle, Sound Technology suppressor, and Choate stock.

The Savage Model 110FP Tactical Rifle is based on the same action used for the company’s M110 long action sporting rifle, which has been in production for decades. The bolt features a somewhat flexible attachment between the locking lug module and the rest of the bolt. This allows the lugs to transfer an identical amount of pressure to the receiver upon firing, while more traditional locking lug designs such as seen on the Remington M700 action can allow each lug to push against the action with different pressure, causing the action to twist in an asymmetric fashion. This adversely affects accuracy. While this phenomenon may not be critical for typical law-enforcement applications, the effect can be real and measurable. This problem with fixed Mauser-type locking lugs can be cured by having a competent smithy turn and lap the lugs for optimum fit and smoothness, but the Savage does not require this costly custom operation for optimum accuracy.

Another advantage of the Savage Tactical Rifle is that a cold shot strikes at the same place as the second and third shots. At a recent sniper training class, an instructor armed with a Savage 110FP competed against a student whose department invested in a very high dollar Teutonic sniper rifle with hammer forged barrel. The expensive weapon’s cold shot was unacceptably far from subsequent shots. While the second and third shots walked closer to the center of subsequent warm shots, shot placement of the first few rounds was still unacceptable. Since accurate placement of the first round is critical and the spendy weapon was not up to the task, the law-enforcement sniper with the Teutonic Wundergewehr washed out of the course. The instructor proved that the Savage Tactical Rifle provides excellent accuracy including the first shot out of a cold barrel.

My own experience with the 7.62x51mm (.308 Winchester) variant of Savage 110FP is that the Tactical Rifle tends to produce approximately 1.5 MOA five-round groups (measured as maximum center to center distance, as opposed to maximum outer edge to outer edge of the group) with Federal 308M ammunition using the factory stock and 1.2 MOA groups using a Choate stock.

Measuring Groups for the Record

Two factors can introduce significant bias when trying to determine the intrinsic (as opposed to practical) accuracy of a rifle: (1) using enough scope, and (2) using a reproducible method for determining group size. Since the following discussion on the performance of the suppressed Savage Tactical Rifle will be discussing some improbably small groups, it is essential to establish the procedures used to generate these numbers. The casual reader might well go ballistic, if you’ll pardon the pun, when I claim a group size that is smaller than the diameter of the projectile. “Did that fool use a squeeze bore or is he simply full of BS?” they might ask. Here’s the methodology I used and why I used it.

Using enough scope is important to really determine the intrinsic accuracy of a system, so we used a Tasco 6-24x44mm World Class TS Target telescopic sight for accuracy testing. While 24 power is about minimum magnification needed to really push the edge of the envelope in terms of assessing maximum intrinsic accuracy of a very accurate rifle, many authorities prefer a 10-power scope for tactical applications.

More than 12x for a tactical scope exaggerates mirage and provides a narrow field of view, while less than 8x adversely affects shot placement. Some snipers like a variable-power scope so they can adjust the scope to low power for defensive shooting at short range, while others prefer a fixed-power scope for its superior durability. U.S. Army and Marine Corps snipers currently use fixed-power 10x scopes on their latest rifles.

Then there is the matter of how to accurately and precisely measure group size (accurately and precisely mean very different things to a statistician). The accepted convention is to measure a group by determining the distance between the centers of the two bullet holes that are the most widely separated shots of a group. This method is much more attractive than measuring from the outermost edges of the holes (or even the innermost edges of the holes) since the center-to-center method is not biased by the diameter of the projectile. The method works equally well for .17 caliber and .50 caliber projectiles.

The problem is that the center of the hole is actually missing, so the precise center must be estimated. This means that the accurate (i.e., reproducible) measurement of an inferred point in space can be a challenge. I used an inferior method for years, a method that is still widely used today. I employed a caliper to measure the outermost edges of the two most widely separated holes, and then I subtracted the bullet diameter. This technique is commonly used by many benchrest shooters, some benchrest competitions, and some gunwriters. It’s a logical method. But it is flawed, as colleague Bill Beatty pointed out to me (to my eternal gratitude). While my old method does not introduce a significant bias in the data when reporting accuracy to the nearest whole minute of angle, the procedure is not satisfactory when reporting group size to the nearest thousandth of an inch.

I’ve subsequently learned that this traditional technique has two fundamental liabilities. (1) One cannot determine exactly where the location of the outer edge of a bullet hole lies. And (2) the paper stretches as the bullet pushes through the target, so the hole in the paper does not have the same diameter as the projectile. Several individuals have designed and marketed target-measuring fixtures based on the principal that people have a remarkable ability to determine when two circles of different diameter are concentric. Dan Hackett has written outstanding articles for Precision Shooting magazine on both the problem of how to measure groups and various commercially available target-measuring fixtures. Far and away the handiest device is a modified vernier caliper designed and marketed by Orrin Hunt (Hunt’s Bullets of Jacksonville, FL; 800-645-3140 code 73).

Hunt machines a hole through the closed jaws of a caliper that is slightly larger than the nominal caliber, so that precisely half of the hole is in each jaw. He also adds a chamfer to the top of the hole, which is critical for the proper optical effect. To measure a group, simply center the pair of bullet holes in the pair of semicircular notches in the caliper jaws and read the group size on the caliper dial. Testing by Hackett on 50 targets with a Jones testing fixture and the Hunt calipers suggests that Hunt’s solution varies by no more than 0.003 inch from using the Jones fixture. Hackett also makes the interesting point that 0.003 inch is less than the difference one normally sees when two different people measure the same group with the same instrument.

This has several interesting implications. (1) The same person should always be responsible for measuring group size, whether the results will be used for publication or determining the rankings at a tournament. And (2) while group sizes are commonly reported to the nearest 0.001 inch, the inherent variability of such measurements means that last decimal place is not truly a “significant figure” in a statistical sense. Just because the caliper reads to the nearest 0.001 inch doesn’t mean that number is meaningful in this application. Therefore, I shall shy away from reporting group size beyond the nearest 0.01 inch when discussing the accuracy of a firearm. Frequently, however, simpler numbers will more readily convey important trends. Comparing the effects of the factory and Choate stocks, for example, merely requires reporting to the nearest 0.1 MOA.

The observed difference in accuracy using the factory versus Choate stock on the Savage 110FP rifle is probably due to two factors: (1) the barrel is free floating in the Choate stock but not the factory polymer stock, and (2) the aluminum bedding block in the Choate stock provides superior rigidity and durability. Adding a Dark Star suppressor generally reduces group size to about 0.4 MOA with a 20 inch barrel, because the weight of the suppressor reduces barrel harmonics, as does shortening the barrel. The sound suppressor also reduces apparent recoil by about 50 percent.

The Federal 308M load features a 168 grain (10.9 gram) Sierra MatchKing HPBT projectile. The Savage .308 caliber barrel features six-groove rifling with a right-hand twist of 1 turn in 10 This is a very good design feature even if the result is not cosmetically appealing. The rifles evaluated in this study had barrels shortened to 18.5 inches (47.0 cm) for urban applications, although suppressor designer Mark White of Sound Technology and I both prefer a barrel length of 20-21 inches (50.8-53.3 cm) whether or not a suppressor is added.

While a Kahles ZF69 6×42 telescopic sight was fitted to the rifles for sound testing and photographs, a Tasco 3.5-10x50mm World Class Plus variable scope with .30 caliber reticle and matte finish would be an appropriate economy tactical scope for this rifle (the Tasco 10×42 and 10x42M Tactical/Sniper Scopes with 30mm tube cost roughly three times more than the World Class Plus scopes). System weight of the rifle with 18.5 inch barrel, Choate stock, Sound Technology Dark Star Mk2 suppressor, and Kahles scope is 17.0 pounds (7.7 kg) with an overall length of 53.0 inches (135 cm).

The Model 110FP’s bolt features an enclosed bolt face for strength and safety; both the bolt and trigger are finished in a black titanium nitride that provides a smooth hard surface. The barrel and action are blasted with steel shot and receive a hot-blued finished, while other parts are blasted with glass beads and then also receive a hot-blued finished. The ambidextrous three-position safety is located just behind the bolt. Push rearward to engage the safety and lock the bolt closed; move to the middle position to cycle the bolt while preventing the weapon from firing; or push forward to fire. This is a nice bit of engineering. A dual-function lever on the right side of the receiver just forward of the bolt handle is not only the bolt-release catch but also serves as the cocking and sear-trip indicator. The lever assumes an elevated position when the striker is cocked. Lock time, which is the time between sear release and primer detonation, is very fast. While the Savage bolt is superior in some respects to a Remington M700 bolt, the Savage trigger is vastly inferior to the Remington’s.

The Savage 110FP comes from the factory with a grizzly trigger that has at least a 6 pound (2.7 kg) sear release, while the trigger pull for a sniper rifle should fall between 2.5 and 3.5 pounds (1.1 and 1.6 kg), with 2.5 pounds being ideal. The sear release on the Savage trigger can be adjusted that low by a smithy, but reducing the sear release below 3.5 pounds may deactivate the safety. Therefore, optimum trigger pull on the Savage based on the design of the trigger and safety—rather than on the operator’s wishes—is probably 4.0 pounds (1.8 kg). Anything more will adversely affect accuracy. Anything less will adversely affect safety. While Sound Technology can provide a trigger job for $55, Mark White would prefer to install an aftermarket trigger by Timney, Bold, or Arnold W. Jewell if and when models become available for the Savage rifle.

The other weak link in the Savage Tactical rifle is the black polymer stock that comes from the factory. The front of the Savage stock bears against the barrel, which significantly degrades accuracy. Since the Savage stock lacks pillars for the action screws, tightening the screws can cause the bolt heads to dig into the stock and the bolts to protrude into the bolt path, where they will interfere with operating the rifle. Furthermore, the overall stock design is more suitable for a sporting arm than a sniper rifle. This is a particular liability when a suppressor is added to the system. Choate’s Ultimate Sniper Stock provides a very cost effective replacement for the mediocre Savage stock.

Ultimate Sniper Stock

Designed by Maj. John Plaster, who is a highly regarded authority on sniping and sniping equipment, the Ultimate Sniper Stock is built from 6 pounds (2.7 kg) of DuPont Rynite SST-35 polymer. The Rynite is injection-molded around a precision machined aluminum bedding block that provides drop-in installation for the Savage Model 110FP. Developed and fabricated by Choate Machine & Tool, Inc. (P.O. Box 218, Bald Knob, AR 72010; phone 800-972-6390, fax 501-724-5873), other variants of the stock are available for Remington short or long actions, and the currently produced Winchester Model 70.

Plaster incorporated a number of desirable features into this design. While the action is rigidly held by the aluminum bedding block, the barrel floats freely, even with the installation of a suppressor. When a Dark Star suppressor is installed on an 18.5 or 20 inch barrel, the system balances naturally at a hollow in the forestock that features molded stippling for a positive grip. This sharp stippling is also found on the stock’s pistol grip. Finished in a matte O.D. green color, the stock features a thick rubber recoil pad that has five height adjustments. Removable spacers enable increasing the length of pull from 13.25 inches (33.7 cm) in 0.25 inch (6 mm) increments. A removable knob at the rear bottom of the stock can be used for fine elevation adjustments, and an angular ramp inside the cutout stock is superbly engineered for holding the stock into the shoulder with the nonfiring hand. The cheek piece adjusts forward and backward, and two cheek pieces are furnished to accommodate standard and high scope rings.

The top of the forestock has a 1.25 inch (3.2 cm) barrel channel and four tie-down slots for attaching camouflage. The 2.38 inch (6.0 cm ) wide bottom of the forestock is angled to enable easy height adjustment and contains an Anschutz-type accessory rail that will accept a bipod. Recessed Uncle Mike’s sling swivels are incorporated on both sides of the forestock and both sides of the butt stock which provide for a number of practical carry modes. Large serrations on the bottom of the butt stock and the forestock (just behind the accessory rail) help the rifle grip sandbags. The sloped bottom of the forestock makes elevation adjustments from a supported hand or sand bags easy by simply sliding the stock on the rest, and the arrangement also keeps a Harris bipod angled toward the barrel so it is less likely to snag on brush during a stalk.

The stock readily accepts camouflage paint of the sort used on duck boats. And, finally, a compartment in the grip can be used for adding a counterweight of lead shot or for storage.

It’s a lot of stock for $160. More importantly, Choate’s Ultimate Sniper Stock provides a very stable shooting platform that enhances both the intrinsic and the practical accuracy of the Savage Tactical Rifle, especially when a suppressor is installed. My only significant criticism of the stock is that the molded stippling is too sharp for my taste unless the operator is wearing gloves. If this is a problem for an operator, a few minutes of light sanding can soften the points to the individual’s satisfaction. Another potential problem of the Choate stock is weight. At 6 pounds (2.7 kg), the Ultimate Sniper Stock weighs 3 pounds (1.4 kg) more than the standard HS Precision Tactical Rifle Stock. Nevertheless, the added weight should not be a liability in the real world, especially for law-enforcement applications. While the Choate stock is butt ugly, handsome is as handsome does. The Ultimate Sniper Stock makes the silenced Savage Tactical Rifle a serious contender—especially when fired from sandbags or a Harris bipod (which can be fitted to the accessory rail using an optional accessory bar with thumb screw that comes with the stock).

Dark Star Suppressor

Sound Technology’s Dark Star suppressor was designed by Mark White, who has been making significant contributions to precision shooting and suppressor technology for more than a decade. His suppressed .22 rifles and pistols, for example, tend to be the most accurate silenced .22s in the marketplace in my experience. It will come as no surprise to suppressor cognoscenti that the new Dark Star suppressors provide outstanding sound reduction while actually enhancing rifle accuracy. Two variants of this suppressor are available, since different end users have somewhat different operational requirements. Both versions feature steel tubes with a diameter of 1.75 inches (4.4 cm), which telescope back over the barrel for 7.0 inches (17.8 cm) to reduce the overall length of the weapon. The two-point mounting system also maximizes rigidity and alignment between the barrel and suppressor, and features a unique conical configuration that gives Sound Technology suppressors two unusual characteristics. (1) When dismounted and then remounted onto the barrel, the weapon does not need to be re-zeroed. All other suppressors in my experience require re-zeroing the parent weapon every time a can is screwed onto the barrel, unless installed with a torque wrench to an optimum number of inch-pounds or the suppressor uses a quick-mount system that always mates the suppressor to the barrel in exactly the same way every time. And (2) the mount design is self correcting if and when the threads on the suppressor or barrel begin to wear. The suppressors are finished with a matte black baked-on molybdenum resin.

The Dark Star Mk1 is optimized for subsonic ammunition but provides world-class performance with supersonic ammunition as well. The Mk1 is 16.75 inches (42.5 cm) long, contains two symmetric and five asymmetric steel baffles, and weighs 3.3 pounds (1.5 kg). The Mk1 increases a rifle’s overall length by 9.75 inches (24.8 cm). The Dark Star Mk2 is optimized for supersonic ammunition but performs very well with subsonic ammunition as well. The Mk2 is 18.0 inches (45.7 cm) long, features two symmetric steel and 10 asymmetric aluminum baffles, and weighs 3.1 pounds (1.4 kg). The Mk2 increases a rifle’s overall length by 11.0 inches (27.9 cm).

I tested the performance of these suppressors using the specific equipment and testing protocol advocated at the end of Chapter 5 in the book Silencer History and Performance, Volume 1. The temperature during the testing was 52øF (11 øC).

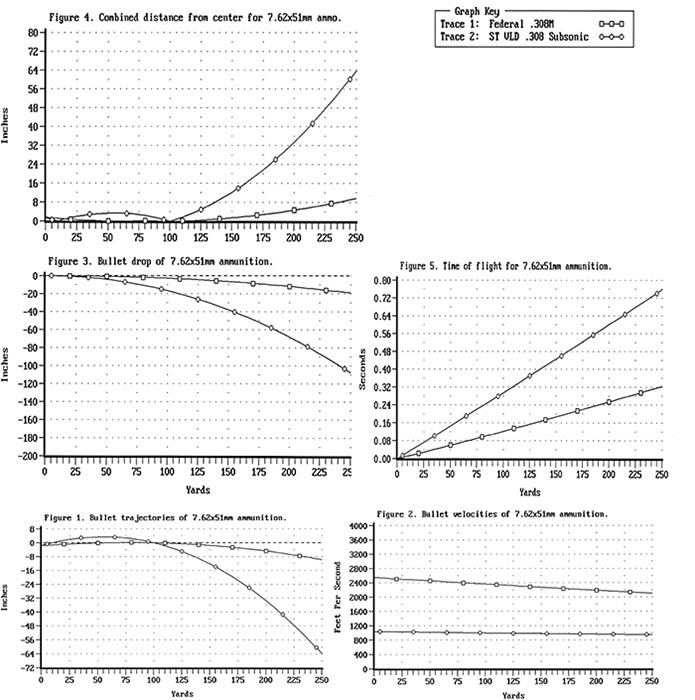

The sound signatures, more properly called the Sound Pressure Levels (SPLs), are shown in Table 1. These data represent the mean (average) value of at least 10 shots. The Federal 308M produced an average velocity of 2,543 fps (775 mps) in the 18.5 inch Savage barrel, while the Sound Technology subsonic match produced an average velocity of 1,039 fps (317 mps). The unsuppressed Savage Tactical Rifle with 18.5 inch barrel had an unsuppressed sound signature of 166 decibels with Federal 308M ammunition and 153 dB with Sound Technology subsonic match ammunition, measured 1 meter to the left of the muzzle as per MIL-STD-1474C.

The Dark Star Mk1 and Mk2 suppressors both produced lower sound signatures than one of the best .30 caliber rifle suppressors of all time, the M89 from AWC Systems Technology (which parenthetically cost three times as much as the Dark Star). Comparing the Sound Technology and AWC suppressors using these numbers is a bit misleading, however, because the McMillan M89 rifle produced louder unsuppressed SPLs than the Savage 110FP. A more meaningful way to compare suppressors tested on different weapons or on different days is to compare the net sound reductions, as shown in Table 2. This comparison shows that the Dark Star Mk1 equals the performance of the M89 with both supersonic and subsonic ammunition, while the Dark Star Mk2 exceeds the performance of the M89 with supersonic ammunition but falls short of the M89 with subsonic ammunition. The Dark Star Mk2 is nevertheless remarkably quiet with subsonic match, providing a lower sound signature than some mainstream integrally suppressed .22 rimfire rifles. It is safe to say that the Dark Star suppressors from Sound Technology are world-class performers.

One interesting aspect of suppressor performance not revealed by the data in the accompanying tables is “first round pop.” This phenomenon occurs when secondary combustion gases and unburned powder residue combine with the oxygen in an unfired suppressor—especially one of large volume—to produce loud instantaneous combustion just beyond the muzzle of the barrel. The first round of 308M ammunition through the Mk1 is 3 dB louder than subsequent rounds, while the Mk2 does not exhibit any first-round pop. This is a significant technological achievement, since most .30 caliber rifle suppressors exhibit this phenomenon. Even the impressive AWC M89 suppressor produces a first-round pop of 3 dB. Since the bullet flight noise of a supersonic .30 caliber projectile is about 149 dB at 1 meter from the bullet flight path, this 3 dB first-round pop is not a significant problem in the real world. Neither Dark Star variant produces a first-round pop with Sound Technology subsonic ammunition, which produces a bullet flight noise of about 110 dB at 1 meter from the bullet flight path.

Conclusions

While there is no substitute for a crisp 2.5 pound sear release on a sniper rifle, the Savage Model 110FP with tuned 4.0 pound trigger pull and Choate Ultimate Sniper Stock delivered sub-half-MOA accuracy with a shortened barrel and Sound Technology Dark Star suppressor, a considerable improvement over the 1.5 MOA delivered by a factory original Savage Tactical Rifle with no suppressor. The suppressed rifle’s sound signature with supersonic ammunition is far below both bullet flight noise and the pain threshold, while the sound signature with subsonic ammunition is less than a currently manufactured integrally suppressed .22 rimfire rifle. The Dark Star was so quiet with subsonic fodder that I did not hear Mark White fire the weapon less than two car lengths away, while I was concentrating on setting up the sound test equipment used for this study. Only the warm rear of the suppressor, the smell of powder combustion gases, and the hole in the bulls eye 100 yards away proved that the rifle had been fired.

While the expensive Accuracy International and Gemtech suppressed sniper rifles are clearly superior tools (at least with supersonic ammunition), they cost four to seven times as much as the Savage Tactical Rifle with Choate stock, Tasco 3.5-10x50mm scope, and Sound Technology Dark Star suppressor. Yet the bottom line, in this case, is the bottom line. The Savage, Choate and Sound Technology components together form a rifle system of synergistic excellence at a package price that is comparable to just a top-of-the-line suppressor from another manufacturer. This system has the capability to solve any realistic tactical problem that is appropriate for a law-enforcement officer to address with a precision rifle of .308 caliber.

Choate Machine and Tool, Inc. P.O. Box 218 Bald Knob, AR 72010 800-972-6390 Catalog $2

Savage Arms, Inc. 100 Springdale Road Westfield, MA 01085 413-568-7001

Sound Technology P.O. Box 391 Pelham, AL 35124 205-664-5860 Catalog $5

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V1N1 (October 1997) |