By George E. Kontis, PE

Family Planning

Designed by John M. Browning, the .30 caliber M37 machine gun evolved as a variant of his M1919 to be used in tanks and ground applications. In spite of the added solenoid trigger, new capability to feed from right or left, and its high reliability, the future of the M37 as a tank weapon became tenuous at the end of World War II. The M37 was not chambered for the new NATO caliber and lacked important features desired in an under-armor weapon.

In 1951 the Ordnance Corps convened a conference at Ft. Knox to discuss the military characteristics (MC’s) desired in a new machine gun. The new gun must fire the recently adopted 7.62mm NATO cartridge to be common with the M14 rifle, the M60 machine gun, and other NATO country small arms. It would be required to use the M13 link, the same forward stripping metal link used by the M60. It all made sense; simplified logistics with common ammo and link.

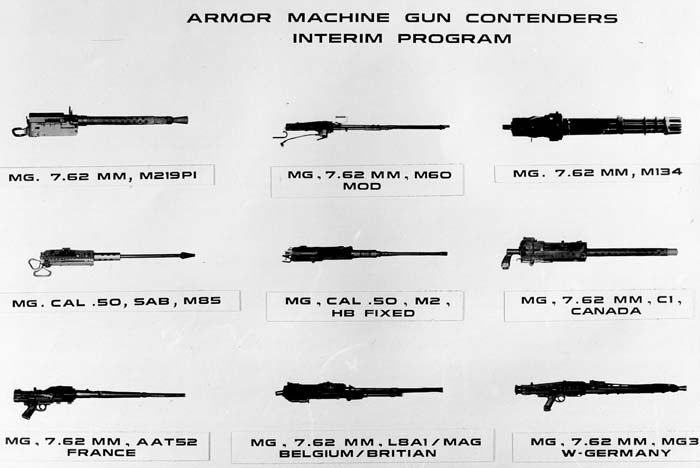

A new gun was to be designed specifically for armored vehicle applications with emphasis on the desired features outlined in the Ordnance Corp MC’s. The most important of these was the length from the front of the feed way to the aft of the weapon. This distance is important in tank design because it determines the amount the machine gun must intrude into the tank’s turret. The longer this distance, the larger and heavier the turret must be. As long as the weapon’s feed is inboard, it can be fed and maintained while the rest of the machine gun can protrude outside the turret. (In the Army photograph comparing receiver lengths between the M37 and M73, the aft rather than the front of the feedway was selected as the forward most measurement. This is presumably because the two machine guns fire rounds that are different lengths so using the aft of the feedway in this case might be better for this comparison.)

Four guns were considered for the armor role with a shoot-off and comparison test considered, but never conducted. The leading candidate was a Springfield Armory design, the T197. Some design work had been started on the T197 but money ran out when the Korean War ended. Weapon development money remained tight and funds did not become available until January 1956. As development had started on the M60 main battle tank and the new weapon was to be the coaxial weapon, the gun design team was challenged to have the gun ready for user testing by 31 May 1958.

The Birth

Leading the Springfield Armory design team for the T197 was Mr. Richard (Dick) Colby, noted inventor and weapon designer. Colby is better known in small arms history for his later development work on the SPIW (Special Purpose Individual Weapon) program. Dick was an innovative designer and challenged his team to not only develop a machine gun that would meet every one of the Ordnance Corps MC’s but to have these guns ready by the May deadline.

Initially the T197 was to be a gas operated weapon but both military and industry did not favor gas operated guns. Past experience had shown that gas residue was a huge cleaning and fouling problem. The gas port in gas operated guns would continually erode, increasing the firing rate with continued use. What also could not be ignored was the durability and high reliability of the .50 cal. M2 Browning. And who could argue with that logic? Today at almost 100 years old, the short recoil cycle M2 is still in use.

Colby selected the Browning short recoil cycle for the T197 but soon found that the recoiling components were too heavy for reliable cycling. So, it was back to gun gas to get the added power – but this time in the form of a recoil booster. A pocket was formed at the end of the barrel so when gun gas reached this point the gas gave the barrel a rearward push to help complete the cycle. Unfortunately, there is nothing gentle about gun gas inside a barrel; it is very high pressure gas that acts over an extremely short period of time. The T197 muzzle booster gave the end of the barrel such a smack that it caused the firing rate to soar; upwards over 1,000 rounds per minute (rpm), far above the desired rate of 450-550 rpm.

To fix this, Colby’s team developed a rate reducing mechanical delay mechanism. This was a series of sear trips and springs that delayed the fall of the hammer. The rate reduce slowed the overall firing rate but the recoil and counter recoil strokes of the barrel extension were as fast as ever. Only when the barrel extension came forward and stopped would the rate reducer spring into action, releasing compressed springs and sear trips until the hammer was allowed to fall. The ultra high speed feed extraction and ejection motions (and the problems associated with them) were still there.

The nice feature of Browning’s short recoil cycle was that the barrel, bolt, and barrel extension recoiled as a unit within the barrel jacket and receiver. The breech remained locked for a long time, allowing chamber pressure to drop to a safe level when the breech was opened. This limited the amount of toxic gun gas expelled into the turret.

To their credit, the internal workings of the T197 were designed so the receiver of Colby’s gun was about 8 inches shorter (aft of feedway to end of receiver) than the M37. The T197 could be switched from right hand to left hand feed without additional parts. Even the charger could be swapped from either side of the receiver easily and with onboard parts. The barrel was designed for quick and easy replacement and no headspace adjustment was required. To minimize barrel wear, the hottest part of the barrel was lined with a high cobalt material, called Stellite. There was no shortage of design innovation in the T197.

While most vehicle mounted weapons are secured by their receivers, the T197 was mounted in the tank by its barrel jacket, with the receiver cantilevered in mid air behind it. This arrangement made for easy barrel replacement as the receiver could quickly be detached from the barrel jacket by pulling one of the two quick release pin plungers connecting them. To change barrels the gunner pulled one of the pins and the receiver pivoted away exposing the end of the barrel. An insulated mitt was to be kept on board for removing hot barrels.

The bolt and feed rammer were a huge departure from conventional design. In most weapons the bolt is a one-piece affair designed to feed and extract ammunition plus provide locking means to react firing loads. In the T197, part of the bolt was a rammer with two long fingers; the upper one was rigid, designed to push cartridges forward out of the link while the lower finger could pivot in order to snap under the cartridge rim for fired case extraction. Locking the breech was achieved by a second component as the rammer wasn’t designed to take the breech loads. The two rammer fingers were made long and skinny so a cross bolt could pass between them, engaging both sides of the barrel extension in order to react against the firing loads.

When the breech was locked, the bolt was behind the case and the feed rammer was behind the bolt. This meant that the T197 design required two firing pins – one in the bolt and a second in the feed rammer body. The hammer could not be located on the weapon centerline as it would interfere with case ejection, so it was mounted on the left inside wall of the barrel extension. This meant that the firing pin in the feed rammer had to be mounted on an angle to the bore centerline. To fire, the hammer hit the off-centerline pin in the rammer that in turn hit the on-centerline pin in the lock block, which in turn hit the primer.

Colby’s team used a cam on each side of the receiver to accelerate the feed rammer in relation to the barrel extension so feed and ejection could occur. Two rollers on arms served as right and left side cam followers and worked with extraordinary efficiency to move the feed rammer at high speed, stripping and feeding cartridges on the forward stroke and ejecting fired cases on the recoil stroke.

Fired case ejection began with two spring-loaded gripping pads at the end of an arm connected to the cam follower arms. The arm rotated upwards to meet the fired case, which was being held at the end of the rammer fingers. The two gripping pads were then supposed to take control of the case and transport it to the bottom of the receiver where it would strike a fixed ejector surface to send the case flying out the bottom of the receiver.

The feeder was more conventional with two spring loaded plungers in the barrel extension engaging the feeder to pull the belt a full link pitch on the recoil stroke.

The Adoption

Designing a gun with as many unique features as the T197, proving out the design and building production weapons in just over two years was a huge challenge. But on 16 June, 1958, just over two weeks beyond the deadline, four test guns were delivered to the Army Armor Board.

Soon after tests began, the Army realized the muzzle booster would not be acceptable. After 2,000 rounds it became so fouled that the rate of fire slowed until the gun quit working. There were other problems too. The closely toleranced parts in the rate reducer seized in the cold weather testing, and part life was dismal. Accuracy and general performance were considered acceptable, but durability was more than lacking.

Meetings and progress reviews were held with great regularity as there were concerns this weapon and the T175 .50 caliber weapon, later to be designated M85, would not be ready for the M60 tank. Adding urgency to problem resolution was interest from the U.K and Canada, with agreements from both to adopt the T197 whenever it was ready. The U.S. Marine Corps advised their intention to purchase 600 of the new coaxials during the 1960 Fiscal Year. There were other users asking about variants. U.S. Army ground forces expressed an interest in a flex version for tripod firing and a helicopter version was on the drawing boards.

Finally, part life was increased and muzzle booster cleaning intervals were raised to 3,500 rounds thanks to a joint effort between Frankford and Springfield Armories. Much progress had been made but functioning problems continued. These were considered insufficient to bar adoption so the T197 was type classified STD-A on 14 May 1959 and designated M73. She was now officially adopted by the Army. Mama had a new baby!

Childhood Illnesses or Fatal Disease?

In retrospect, those functioning and durability problems should have been looked at more closely as they were indicative of a number of inherent design flaws. The most serious of these were:

- The quick release plungers that separated the receiver from the barrel jacket were too loose in their mounting. This allowed the receiver to shake and bounce during firing and affected the headspace causing case separations and other malfunctions. The resultant “spongy breech” plagued the design to its end.

- The feed rammer fingers couldn’t hold the round or fired case reliably, especially with the receiver shaking madly during firing. This resulted in round or fired case control being lost, causing jams.

- The spring-loaded gripping pads on the ejector were not reliable, resulting in failures to eject. The fixed ejector at the bottom of the receiver would not allow the weapon to function upside down or on either side as ejected cases would not clear the receiver. Functioning in all orientations is a standard requirement for all U.S. Small Arms.

- The use of two firing pins that were not on the same axis invited light strikes and other reliability problems.

- There were too many parts in the weapon – a total of 305. Simple designs generally have 200 parts or less.

In 1963 a new booster was sent out into the field for installation on all weapons. The stated purpose was to “…provide increased gun recoil velocity for improved ammunition compatibility.” With this we are led to believe that the problem with the gun was the ammunition, all along. The new muzzle booster would push the recoiling parts even harder, making the gun run even faster. This was hardly the recipe for increased reliability. Mama had an ugly baby, but nobody wanted to tell her.

Life in the Army; Daddy Leaves Her

Unlike other well-managed weapon programs, the M73 was never examined for producibility, nor were formal engineering drawings made or tolerance studies conducted. Rather, the Army chose to go into production using the R&D drawings, amending them as needed to make the parts producible. Design changes were made based on limited R&D tests. Springfield Armory was placed in charge of production.

Amazingly, M73 weapon production and fielding proceeded normally and for a period of three years. There were no field reports, either positive or negative, received by the program manager. Suddenly in 1964, a unit in Europe reported a high incidence of malfunctions – more specifically: short recoils and damaged cartridge cases. Attention turned to the ammunition, where a particular run of 7.62mm ammunition, designated Army DODAC (Department of Defense Ammunition Code) A-127, would not work with the M73.

A technical team was sent to assess the problem with three action items initiated:

1. Inspect and rebuild all of the guns in Europe.

2. Emphasize training, maintenance, and operational procedures.

3. Review ammunition production with a critical look at inspection procedures and acceptance practices. There was every indication that it would be necessary to establish a case hardness specification.

Guns with very little use now had to be inspected and rebuilt. Training was emphasized because the technical team couldn’t bring themselves to blame the gun; it had to be the fault of the gunner. Nor would the Army’s weapon community overlook the ammunition. Ammunition production procedures were to be closely scrutinized because every one who has ever designed a gun knows when they can’t figure out why it doesn’t work it’s generally the fault of the ammunition. (The converse is true with ammunition manufacturers.) There was nothing in their report about faults with the weapon, but finally the Army did recognize there was a price to be paid for their rush to build the weapon along with their failure to address serious design flaws and producibility issues early in the development phase.

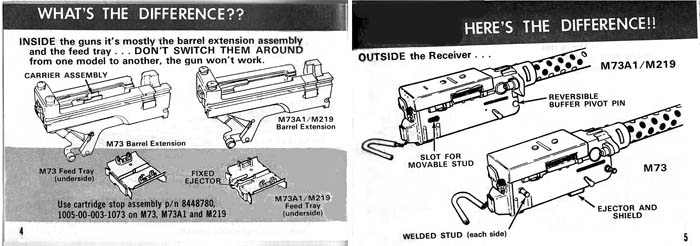

At long last, production engineers set upon the weapon to simplify its manufacture, while product engineers addressed functioning and other problems. The modified M73 became the M73E1 with the major differences being the replacement of the old ejector by a fixed ejector mounted to the feed tray.

An impressive “fire to destruction” test was organized with three weapons firing 64,000+, 74,000, and 92,500 rounds until the receivers failed. New DODAC A-131 ammunition was specified for all machine guns with the older A-127 set aside for use only on the M60. A blind eye was turned to the ammunition commonality issue – one of the primary reasons the T197/M73 was designed in the first place.

Functioning problems scared off other potential users. The Marines decided to use a variant of the M60 for their coax while Canada modified M1919’s to fire 7.62 mm NATO. Wisely, the Brits decided on a coaxial version of the Belgian MAG-58.

At some point in the program and it is not clear where, Dick Colby left the M73 design team. In later years he admitted to designing it but swore it worked well until other engineers and production teams changed the design. Mama’s baby had lost her daddy and life was going to get tougher.

Life in the Orphanage

In 1968, Robert McNamara, then Secretary of Defense, closed Springfield Armory forcing the Army to walk away from a multimillion dollar design and production facility. At the time of its closing, two machine guns were being built there, the M73E1 and the .50 cal. M85. In an effort to save area jobs and to continue production, the Army contracted weapon production and part of the facility to be taken over by the General Electric Company, Armament Systems Department in Burlington, Vermont. Who better to take over this manufacturing than the designer and builder of the world’s most reliable machine guns and aircraft cannons?

There was a mixed bag of personnel at the General Electric Company Springfield Operation consisting of a few Arsenal people, some GE folks from other operations, along with a few new hires. The engineering department was joined weekdays by their new boss, Robert (Bob) Chiabrandy, and me, George Kontis. Bob and I worked all week in Springfield and returned home to Vermont for the weekends.

With new armored personnel carriers and tanks on the drawing boards, GE saw a market for single barrel vehicle weapons and set up an engineering group at the Springfield facility to develop them. Leading the design effort to develop a new family of single barrel weapons was none other than Dick Colby.

Month after month Springfield Armory had produced the M85 and the M73E1 with few problems. It was only after GE took over that problems mysteriously started. In spite of the fact that parts were made on the same fixtures with the same machines by many of the same people, neither gun would function properly in the firing acceptance tests. The M85 was bad, the M73E1 was worse.

At times the rate of fire of the M73E1 was too fast, causing an entire weapon lot to be rejected. Other lots fired too slowly – again reason for rejection. Since the guns were built to print and the prints were supposed to be correct, we engineers had little maneuvering room with the design. Even the slightest change that deviated from the dimensions specified on the drawings had to be submitted for review and approval by the Army design control, now situated at Rock Island Arsenal. Sometimes enlarging the bullet exit hole in the muzzle booster to its maximum allowable diameter would relieve the high pressure and was the cure for fast shooting weapons, but what to do with the slow ones? These guns were all supposed to have interchangeable and interoperable parts so guns with swapped parts were required to meet the same specifications. These were not the only malfunctions. The rammer fingers often lost control of the fired case after extraction, and a loose case in the receiver was certain to induce a jam.

Many at the Springfield Operation who were not former Armory employees felt cheated since both of these gun were supposed to be mature designs. Both were successfully built by the world-famous Springfield Armory. We from GE expected we would only have to build the parts of these two weapons to the Government prints, and follow the assembly instructions to lead to a successful acceptance test. But rare was the month that the production lot of these guns passed the final testing.

George Harris, GE Springfield Operation’s General Manager, was a capable manager and a fine gentleman. George had made his career at GE and was understandably concerned with the poor production line performance of the two guns. Accepted lots of monthly production were the only source of income for the Springfield Operation.

One might expect that Dick Colby’s previous design experience with the M73 would have been an asset in figuring out these problems. But Dick would have nothing to do with the M73, staying with his claim that the gun had worked in the past, but other engineers had made major changes that “ruined” the gun. There may have been some truth in Dick’s assessment.

Really fast firing weapons induced a spectacular failure: a stoppage that began with the ejector. Now that the M73E1 featured fixed ejectors, it was seemingly impossible that the fired case would not eject at high velocity when it hit the fixed ejectors mounted to the feed tray. But the fast moving recoiling components slammed the fired case into the ejectors so hard that two triangular punch marks ripped into the case head, sometimes cutting completely through the case rim. When this happened, so much energy was drained from the recoiling parts that the gun function ceased.

When this malfunction occurred, George Harris was briefed on the situation by Bob Chiabrandy who had organized the test crew and engineers in a study to determine the cause and potential fix. When testing began, George remained in the test cell, pacing back and forth, eagerly awaiting the results.

Although he could easily pass for one of Greek descent, with his looks and maybe even his name, George Harris professed no such heritage. In his youth he worked in a Greek-owned vegetable market and had many Greek friends. One of these local Greeks owned a coffee house which he often frequented after work. When George described these problems to his Greek buddies, one of them presented him with a set of Greek worry beads. The idea was that he could use this string of smooth round beads to keep his fingers occupied as he paced the firing range floor. Now he could look like a Greek and worry like one too.

The range crew, the test engineers, and particularly the Quality Engineer, Paul Hamilakis and myself (both of us from Greek immigrant families) were greatly amused by George’s new acquisition. Paul and I explained the history of the beads and coached him in the characteristic stance of a true Greek worrier. Every day we could count on several range visits from George, only now with his body hunched forward, hands behind his back, nervously flipping a string of beads.

One day, Bill Frigon, our engineering technician, came into work with a gift for George. He had configured some of the “punched through” case heads into a set of custom M73E1 worry beads. George was much impressed and asked for a second set to be sent up to Burlington’s top management. The beads were a hit with the Burlington big wigs too, who fired back the message: “If we can’t make machine guns, maybe there’s a market for these worry beads.”

With a poor financial report resulting from losses at the Springfield Operation, by 1970 GE closed the facility and gave production responsibility of both gun designs back to the Army. GE had come to realize that: Mama had a really ugly baby, but they were too polite to tell her so.

Back with family and a new identity

With new production M60 tanks still in need of machine guns and existing guns requiring spare parts, Rock Island Arsenal was the logical choice to continue M73E1 manufacture. This was a good choice not only because Rock Island had machines and machinists, but because many of the old Springfield Armory personnel ended up there after the Armory closed.

Soon after taking over, Rock Island Arsenal began receiving complaints from Ft. Knox that the weapon was performing poorly. In 1971, small arms management – all old Springfield Armory veterans – decided to send a new hire to Ft. Knox to hear their concerns. He was a young engineer named Neil Burchell. Neil’s job was to evaluate complaints and find fixes to their problems. Given the nature of the problems and the importance of the application, Neil was surprised when he learned that he was the only person from his office working on them.

Like many before him, Neil did his best to fix the problems. The “spongy breech” problem he addressed by using quick release pins that expanded when closed to take up tolerance in the joint between the receiver and barrel jacket. This worked until the expanding pin handles shook apart and had to be safety wired to the barrel jacket. Another approach was to make parts that were “zero tolerance” by precise machining of the joint components to remove as much of the free play as possible. What worked to some extent in the vehicle mount was a “tanker’s fix” that involved securing the back end of the receiver to a point above in the turret using a bungee cord. The gun often shot well when constrained this way, but there was no way to change the barrel quickly so the idea wasn’t practical.

The ejector surfaces were beefed up to eliminate the punched through case rims. Neil used what was then a new welding technique called “electron beam welding” to solve strength and positioning problems with the ejectors, the rails the barrel extension rode on, and the rammer-extractor assembly. Neil found that he could simplify the design by removing the pin through the top of the barrel jacket that oriented the barrel. The gun worked equally well with or without it. With all the changes to the M73E1 and possibly to allay the stigma of the old problems, Rock Island decided to change the designation. Guns with the new features were now called the M219. The rumor at Rock Island was that this number was selected because the new gun was “three times better than the old M73” (do the math). Neil disputes this saying it was just a coincidence that the numbers worked out that way.

The M219 did look a bit more promising. At one point Neil put the gun in a hard stand and was able to fire 10,000 rounds without a stoppage. He was really excited about this until he put the same gun in a tank mount. Just as before, the gun vibrated and shook in its mount, introducing a large number of stoppages. In later testing, Neil found that if the spring rate of the mount exceeded 60,000 pounds/inch, the weapon would have a low incidence of malfunctions. Unfortunately this was stiffer than the tank mount. As M219 problems continued, Neil was joined by another engineer, Jack Plambeck, who assisted in developing fixes for each of the problems: every time firing multiple 10,000 round tests to verify the integrity and success of design changes.

Neil continued his role as the principal interface with Ft. Knox confiding that in the beginning he went there to convince them that there were really no problems with the M73E1 but ultimately they convinced him to the contrary.

Search For Cinderella

By 1971 some in the Army Arsenal system recognized the M219 design left much to be desired and decided to fund a few R&D contracts to see what might be the successor. Eight R&D contracts were let for new and unique 7.62mm coaxial weapons including:

- Two entries from Philco Ford – one externally powered and one self powered.

- A self powered, dual feed, machine gun from Maremont designed by John Rocha.

- A self powered machine gun from Pacific Car and Foundry.

- A compact, short-receiver, Browning short recoil cycle machine gun from General Electric Company (coincidentally, based on a design originally conceived by Dick Colby).

- An externally powered machine gun from Cadillac Gage designed by M16 inventor Gene Stoner.

- An externally powered machine gun from Hughes that became the predecessor of the M242 Chain Gun.

- An entry from Rock Island Arsenal’s own Rodman Labs.

All of these weapons were designed, built, and tested, with many of them showing great promise in the coaxial role. The eight candidates were down-selected to five and evaluation testing of these continued with the intent to find the best one to replace the M219. One day in the fall of 1973, a major world event changed everything.

Oy Vey is your child UGLY

It was October 6, 1973, the day of the Jewish holiday Yom Kippur, when a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria attacked Israel. Egypt and Syria crossed the cease-fire lines in the Sinai and Golan Heights and were met by Israeli M60 tanks. The Israeli’s were victorious, but with little help from their M219 machine guns. The guns had performed miserably and the Israeli’s were not at all happy about it. Israel demanded someone the U.S. Army send over a representative to look at guns and listen to their complaints.

Neil Burchell was the most likely candidate for this task but his supervisor, Bob Henry, refused to let Neil go. Neil had a reputation as a collector of military memorabilia and Bob was sure Neil would either kill himself or become badly injured while out on the battlefield picking up souvenirs. Today Neil admits that Bob was probably right.

The Israeli’s displeasure with the M219 was vented on the U.S. Congress. How could it happen that a world power would develop such a weapon and sell it to their ally? By early 1974, a replacement was mandated and the search for a new coaxial machine gun was on.

By now, Rock Island Arsenal had also given up on the M219. Wilmont Gibson, branch chief, and Dennis Ash, head of crew served weapons, concluded that in spite of their best efforts, the M219 simply could not be fixed.

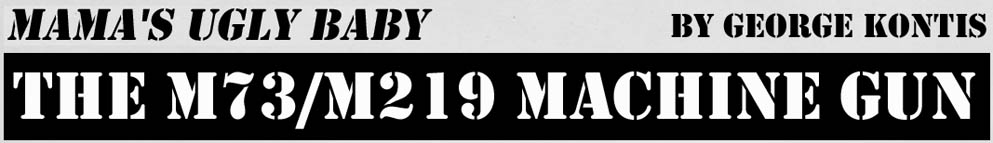

On the Israeli-inspired replacement project, eight U.S. and foreign machine guns, six 7.62mm and two .50 caliber, were evaluated alongside the M219. The Belgian MAG-58, another 1950s vintage weapon based on one of John Browning’s gas operation concepts, emerged as the clear winner. The MAG demonstrated the highest reliability of any self powered machine gun in U.S. testing history and was give the designation M240.

In retrospect, the design of the M73/M219 was an accumulation of novel concepts that should have been thoroughly tested in the application before finalizing the design. The off and on development program challenged the ever-changing design teams with a new learning curve every time the project was restarted. It was a costly program in time, assets, money and loss of face. She was an ugly little baby and somebody should have told her Mama so.

(The Author extends appreciation to the following for their contributions to this article: Neil Burchell for information and insight into the Rock Island Armory days of the M73/M219; Robert Chiabrandy for the gift of the “one of a kind” M73 worry beads; Tom Cosgrove who supplied some early information on the birth of the M73 plus the gun model, and Ms. Jodie Wessemann of the Rock Island Arsenal Museum for providing photos and other pertinent technical information.)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V12N9 (June 2009) |