By James L. Ballou

Excluding the many Browning designed weapons, the Madsen machine gun holds the distinction of being one of the oldest and longest produced machine guns in history. Though used by thirty four different countries, it was never adopted officially by any major nation. It has been chambered in every military caliber used in the world, rimmed or rimless, from 6.5mm to 25mm. Little has been written about this remarkable weapon that introduced the concept of the light machine gun. From its conception in 1902, it remained in continuous production until 1970 when Madsen went out of business.

Both John Browning and Sir Hiram Maxim did what would be considered by today’s standards, virtually impossible: they converted a lever action Winchester 1873 rifle to full automatic. Browning utilized the gas from the muzzle blast to operate a flapper that worked the lever action of the Winchester Rifle and Maxim took the Winchester and made the recoil forces at the butt plate operate the same lever action. Somewhere along the line (approx. 1898) the concept of converting a single shot repeating rifle into a full auto landed in Denmark. Julius Rasmussen used as his inspiration the Peabody-Martini (British) falling block single shot rifle. On June 15th, 1899, he applied for the first patent employing this design. However, in 1902, Lt. Theodor Schouboe was granted a patent on the same principle. No one is clear how this occurred. The gun went on to be produced by Dansk Rekylriffel Syndikat under the patents supplied by Schouboe and, for some reason, the gun was named after W.O.H. Madsen, the Danish Minister of War. It was also manufactured in England and known as the Rexer or DRRS.

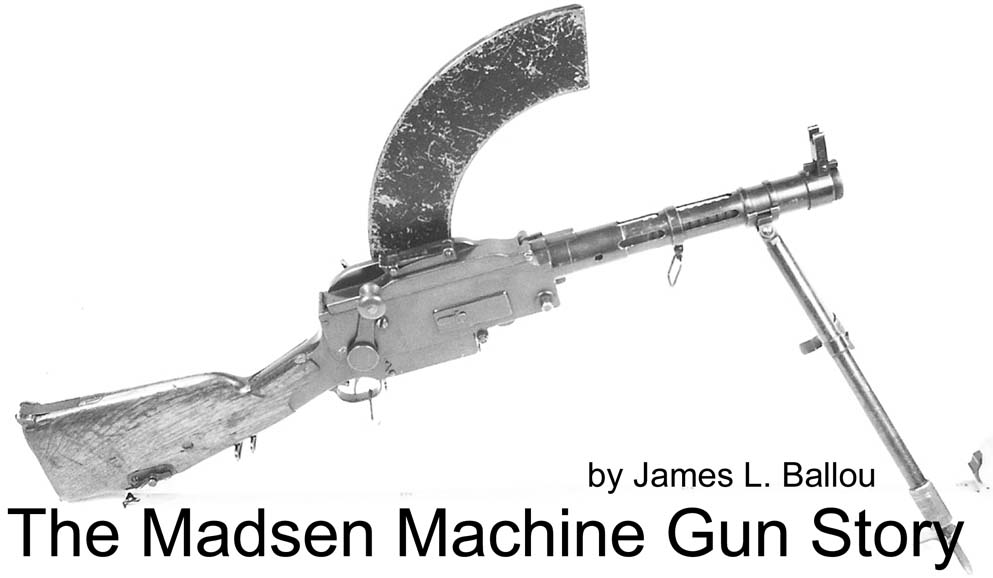

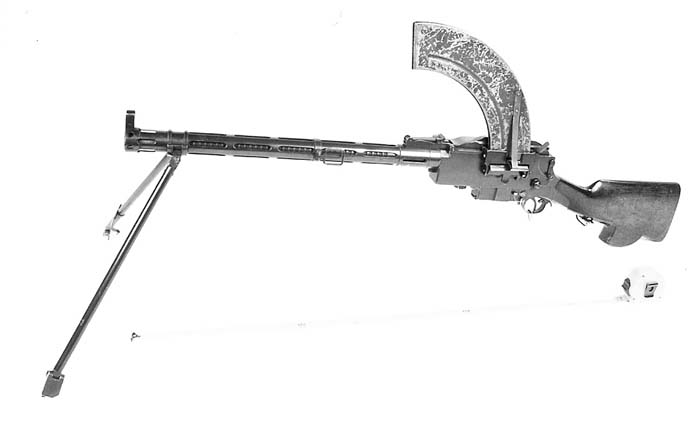

During its sixty eight years of production there were many minor variations of the Madsen – over one hundred are known. However, there were basically three primary models: the first, a magazine fed LMG, the second a belt feed tank or aircraft model, and the third proved the most fantastic adaptability of the design. In 1926, The Dansk Industries announced the development of a 20mm automatic aircraft cannon utilizing the same Madsen mechanism. Though not widely used, a hydraulic buffer allowed for a 23mm version used in German Fokker aircraft.

The first US testing was done at the Springfield Armory on September 9, 1903. A total of 7,163 rounds were fired, during which enough malfunctions occurred to justify the official conclusion that the Madsen weapon had not reached a state of reliability to warrant adoption. Though Lt. Schouboe himself had conducted the firing, he had to rise to a kneeling position to clear stoppages – a condition with which one can certainly sympathize but can be fatal in combat. US special order No. 86 dated August 5, 1921 provided for a further test of the Madsen in .30-06 at Fort Riley, Kansas. Supposedly redesigned, the Model 1919 included provision for both a bayonet and elaborate, detachable flash hider. It was still deemed unsatisfactory.

The Germans experimented with a variety of newly developed weaponry and, as a stopgap, the Germans used approximately 500 Madsens in World War I (referred to as a Muskette and given the designation Leichte Automatische Muskette M15) until they developed the Maxim 08/15 that then became their light weight machine gun of choice.

In 1923, the Dansk Syndicate assigned its chief engineer, Mr. Hambroe, to redesign the Madsen mechanism for more efficiency. All he did was to add a muzzle booster that greatly increased the cyclic rate to 1,000 rounds per minuet making it ideal for aircraft use. He also added a strong spring buffer to absorb the shock of the booster. The real beauty of the aircraft gun was its ability to use disintegrating links and could be synchronized to the propeller.

During WWII, America was equipping the Dutch East Indies with Johnson automatic rifles. Johnson Automatics, better known as Cranston Arms, supplied barrels for the Madsen LMG.

In 1950 the last evolution of the design featured a quick change barrel and a tripod soft mount with a remote firing devise.

By all concepts of logic, this gun should not work as it is a mechanical nightmare – but it does indeed work. The key to its operation is a cammed “switch plate” that allows recoil to perform the actions of loading, firing, extracting, and ejecting the spent rounds. The term “switch plate” is a 19th century expression of a device that caused a sequence of functions to be completed in rapid succession for a railroad train. In this case, a switch plate multi-tasks the functions for the machine gun and is the mechanical heart of the weapon. The Madsen is known as a long recoil system, i.e., the barrel and breach mechanism reciprocate together inside of a barrel shroud and receiver box. This action works the lever that, like the Martini Rifle, accomplishes the task of ramming the round into the chamber with such force that it often deforms the cartridge case. If the round does not fire it is difficult to clear the stoppage.

Test firing was conducted with Madsen Mle. 1950, serial number 1475. The gun did not function flawlessly. It soon became evident that great care had to be taken in placing the magazine into the top or it would spill rounds into the magazine well. When a shell got down into the mechanism it did not chamber or fire and it was a chore to remove the offending round.

As mentioned above, the power of the ramming arm often distorted the case making it a ramrod job to remove from the chamber. Then, one had to carefully work the case to the ejection port that is part of the reciprocating mechanism attached to the barrel. Nevertheless, when it did work, it was a joy to fire. Amazingly, it was found that the magazine was unnecessary to fire the weapon. Four rounds could be dropped into the magazine well and the gun would fire all four. Single shots were readily obtained as the cyclic rate was approx. 550 rpm. The bipod was not sturdy enough to prevent dumping the machine gun over into the dirt. The offset sights were sufficient and accurate. The magazine is a top feed double stacked 30 rounder until it enters the gun. It then becomes a single feed with the round being retained by a large spring that also acts as a magazine catch. There are several positive points about the Madsen design. First, its top magazine feed allowed gravity to enhance its entry into the mechanism; second, a bottom feed that was positive and powerful; and finally, the Madsen fires from an open chamber reducing the chance of a cook off.

When one carefully examines this design, there is a tendency to write off the Madsen as a “mechanical monstrosity” that like the Bumblebee should not fly. But, upon more careful examination, the designer, whoever he may be, took a tried and true Martini rifle and applied 19th century railroad technology, added robust parts, and designed a machine gun that is found in museums around the world. At the old MOD Pattern Room there was an entire long table devoted to Madsen LMGs, with more national crests than the fabled Roundtable. Many armies tried the weapon and modified strategies around it to apply the weapon. This is an unsung pivotal weapon in the small arms field. In the end, it was a versatile design that deserves a better niche in history.

| MADSEN AUTOMATIC MACHINE GUNS |

| Specifications: | M1902/04 | Model 1924/42 | MODEL 1950 |

| Caliber: | Many | 7.92 x 57J | 7.62×51 NATO |

| Weight: | 20 lbs./bipod | 20 lbs. | 22 lbs. |

| Length: | 45 inches | 48 inches | 45 inches |

| Barrel: | 23 1/8 inches | 24 inches | 18.8 IN. QC |

| Action: | long recoil | long recoil | long recoil |

| Range: | 800-1,000 yds. | 1,000-1,200yds. | 1,200 yds. |

| Feed System: | 40, 30, and 25 rd. | Disintegrating | 30 rd. |

| Cyclic rate: | 400-500 rpm | link | 400-500 rpm |

| Selective | 1,000 rpm | Selective |

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V12N1 (October 2008) |