By Leszek Erenfeicht

Magazines are direct descendants of a charger clip – an en bloc loading device inserted into the internal magazine together with the cartridges. If the chargers were so inserted, why not make a magazine that could be exchanged the same way? Indeed, why not, must have thought James Paris Lee, an American inventor who provided such exchangeable magazines for his prototype rifles of the 1880s.

The first country that adopted his rifle was England, but before the Lee rifle replaced the Martini-Henry as a new trademark of the Thin Red Line, the English introduced so many changes into his design that finally only two original features were left: the action cocked on closing and the exchangeable magazine. Why this was a feature the British wanted for their 1888 Lee-Metford and then Lee-Enfield rifles, nobody knows. The fact is that all through the long years when .303 Lee was the British rifle, NEVER were extra magazines given to or carried by the rank and file Tommy. Each SMLE had one exchangeable magazine in place and stripper clips with extra ammo supply to top it off. Leaving that aside, the first move was made in 1888 when the first exchangeable magazine made it to the hands of the major army.

Ever since then the magazine clips, often just called clips for short, expanded rapidly and now hardly anyone imagines an infantry firearm fed otherwise. Even the cartridge belts are now encased in small containers clipped under the gun, the magazine way. Internal magazines became a proof of obsolescence – pure and simple. When in the 1980s George Kelgren tried to sell his Grendel P-10 with an internal, stripper-filled magazine, he earned many raised eyebrows in response.

Exchangeable magazines come in various shapes, sizes and designs, which can roughly be divided into three main groups: the box magazine; the drum magazine; and the pannier magazine. There are scores of individual designs, but with a little bit of good will, each magazine can be attributed to one of the three groups.

Box Magazines

Box magazines are the most internally differentiated and the most numerous group of magazines. Generally speaking, the box magazine has cartridges laid parallel to the bore (with a few exceptions, like the Czech ZB47 or the German HK G11, where cartridges were set perpendicularly, pointing downwards, or the Belgian FN P90, where bullets are set perpendicularly, pointing sideways) and in layers of different size; mostly single row or double (staggered) row. The cartridges are pressed down between the follower and the magazine lips under the tension of the follower spring. The spring tension on the follower, a small platform pressing on the cartridges, is responsible for both retention of the rounds loaded inside the magazine, as well as for exposing them at the magazine lips, where from they are stripped by the bolt and chambered. Owing to the shape of the cartridge case, sometimes more cylindrical, or conical, the magazine box can be either straight-sided or arced (the so-called banana-clip). Pistol magazines are straight boxed, no matter how conical the cases are. With traditional materials and cutting tools it was too complicated and expensive to make a grip with a curved magazine well to suit a banana-shaped pistol magazine. But now, with all these new polymers, who knows what the future may hold? In automatic weapons it is different, because several dozens of conical cases forced the designers to curve the magazine at sometimes radical angles, including half-circular shapes, like the 20-round 8x50R French magazine for the Chauchat LMG, or the 100-round horseshoe shaped experimental AKMS magazine (fortunately never issued). Even with a radical shape like this, it is nevertheless still called a box magazine.

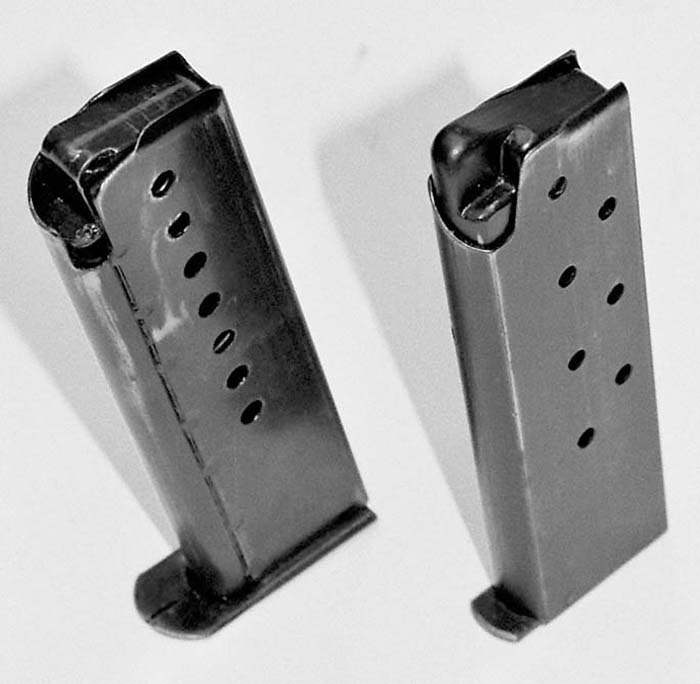

The fundamental difference in magazine designs is the number of the cartridges in a layer. A single row magazine has one round in a layer, and the width of the box is roughly equal to the width of the cartridge. Because of their early abundance, this type of magazine is unjustly deemed the earliest type of box magazine. In fact, the Lee magazine was of the staggered or double row type. These magazines are a little wider than a single cartridge, roughly a case-and-a-half in width. Such an arrangement enables more rounds to be packed into a lower stack: the main purpose of their existence. The name “staggered row” describes the arrangement of the cartridges more precisely than the name “double row”. The simplest rendition of this scheme is a “staggered row – two-position feed” magazine with two rows of cartridges all the way up to the feed lips. It was simple to make such a magazine, but then it necessitated some kind of ramp incorporated into the gun between the lips and the chamber to center the rounds fed from the left and right intermittingly on their way to the chamber. It was not a big problem in a bolt action rifle, due to the slow velocity of the moving parts, but in an automatic firearm problems were inevitable. Thus, single row magazines abounded in early automatic guns of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Cartridges from a single row magazine are always presented on the axis of the chamber, and there are no problems with indexing the round. It was simpler to set the cartridges in a single row and was easier to get the single row magazine working in an automatic gun. Even if it fired a rimmed-cased round, the magazine was straightforward in design and manufacture, but it had one big disadvantage: to get any sizeable capacity meant having to deal with an enormously long magazine. To ease that problem, magazines were set on top of the machine gun (Madsen) or on the side of it (Johnson LMG 1941), so that the long magazine did not stand in the way of a shooter firing it from the prone position. What was good for pistols, could not be found fit for a machine gun.

In 1916, German Hugo Schmeisser found an answer to the problem. He blended both ideas into what we now call a “staggered row-single position feed” magazine. It was a simple arrangement whereby the staggered row portion of the magazine that holds the ammunition fed to the chamber via a single row. These are connected by a so-called “Schmeisser’s Cone,” forcing the two rows of cartridges into a single one. Schmeisser’s magazine was much better than the snail drums he was forced to use with his MP18.I during 1918, but they were only introduced after World War One ended. At the same time an American, Oscar V. Payne, had at last solved the problem of a “staggered row-two position feed” magazine, designing his XX (20-round) stick magazine for the Thompson submachine gun. Both systems were then at each other’s throat for years, each with avid supporters. Another breakthrough came about after World War Two. In the late 1940s, at about the same time in Czechoslovakia and Sweden, a new type of magazine appeared: the wedge-section staggered-row. This was a development of the classic Lee’s “staggered row-two position feed”, whereby the shape of the section makes both rows converge a little so that the cartridges, despite being alternatively fed from left and right, have bullets already centered for smooth chambering without a need for feed ramp. The first wedge-sectioned magazine was introduced in 1948 simultaneously in Sweden (Carl Gustaf m/45B, or Swedish K) and Czechoslovakia (9mm vz.23/25 SMG, then converted to 7.62×25 as vz.24/26).

Another attempt at enlarging the magazine capacity was taken by Carl Schildstroem of Sweden. He designed a double compartment magazine with a single-position feed, giving, in effect, a four-row (twice the staggered row) single-position feed clip for 50 rounds. These were in fact two magazines sharing one set of magazine lips with a Schmeisser’s Cone. This magazine, called the “coffin clip” by the Finnish troops, was introduced for the Suomi SMG. It was too heavy (empty weight about 2 pounds), complicated, and failure-prone to be retained for service for any prolonged length of time. It was dropped soon after the war in favor of the wedge-shaped box. An interesting attempt at reviving the scheme was taken by the Italian company SITES for their M4 Spectre submachine gun. The M4 magazine also has a double compartment feature, but a two-position feed.

An additional novelty is a magazine for the futuristically designed FN P90 submachine gun. At first sight it looks just like a common staggered row magazine made of translucent plastic, but if you look at it closer, it is obvious that it’s single position feed lips are set perpendicular to the cartridge axis. Under the tension of the follower spring each cartridge is rotated through 90 degrees before being exposed in the feed lips for the bolt to strip and chamber. Thus, a submachine gun was designed, which is but a flat box with no projections vertical or horizontal, despite being ready to shoot with a 50 round capacity.

Drum Magazines

Another stage of magazine design evolution was the drum magazine. As the name implies, it is rounded, with cartridges set parallel to the bore, in a helical path, where a spring forces them one by one to the magazine lips. They were another way to extend the capacity of the single row magazine (which variation they really are) without growing to prohibitive size. The first were just that; a single row magazine with their bottom portion rolled. This type of drum was called the snail-drum, and the most famous of these was introduced in 1917 with the Ari-Para, or the M1917 Artilleriepistole variant of a Luger with an 8-inch barrel, tangent sight and detachable shoulder stock. A year later, the same magazine was forced upon Hugo Schmeisser for his MP18.I, becoming the soft underbelly of that weapon. Some see the origin of such a magazine in a rounded belt box with a spooled belt, attached to the machine gun’s receiver.

Another 1919 Oscar V. Payne invention, the L and C (50- and 100-round) drums for the Thompson submachine gun, gave origin to the true drum magazine and no longer had the extended box part. The magazine lips of Payne’s drum were cut in the drum’s side. The clockwork spring moves the “propeller” – a star shaped cartridge container-cum-multiple arm follower, exposing consecutive rounds in the lip’s opening. This was a complicated design, but operated much smoother than the single-follower models because each of the follower arms had to deal with just five or ten cartridges, and not the whole of the drum contents. Payne’s magazine’s most recent rendition is a 75-round drum for the Soviet RPK light machine gun, which provides sort of a missing link between the snail-drum and the Payne drum. It is a multi-follower magazine with a single file attaching part, which for manufacture convenience was shaped to represent a double-position staggered-row magazine box to fit the Kalashnikov magazine catch.

The other variation of the true drum was a design by Oskar Alfred Östmann of the Tikkakoski Oy, manufacturer of the Aimo Johannes Lahti’s Suomi submachine gun. It has a single follower, propelled by a very strong clockwork spring; necessary to overcome the weight and friction of the 70-round content of the drum. It was less complicated than Payne’s drum, but much more susceptible to dirt; increasing the friction and raising the burden on the clockwork spring even further. Despite that, it was the most widely mass-produced submachine gun magazine of the world. What, you never heard of Mr. Östmann and his magazine? What about Comrade Shpagin and his Pepesha drum? Oh, that you know? Well, that’s the same drum. The only difference was that Finns were the first, made it in 9x19mm and paid the inventor royalties, while the Soviets copied it in 7.62x25mm and never paid a dime – but that is another story.

A sub-variation of drum magazines are the double-drum magazines; also called “saddle-magazines”, a German specialty. The first such design originated for the prototype Vollmer’s machine gun from the period of the Germany’s clandestine re-armament after World War One. It was then retained for the MG13 light machine gun, the aerial MG15, and then with the MG34 general purpose machine gun. Contrary to the external appearances and what many so-called authorities state, the latter two were not interchangeable, as they were differing in the height of the magazine lips portion. Such magazines has two separate drums, feeding cartridges to the common feed box with lips on the end, placed between the drums and shaped like a staggered-row two-position feed box magazine. Then the bolt strips the cartridges from the lips, chambers them and fires in an ordinary way. Most of the German saddle-drums were attached from the top (MG 15 and 34), or from the side (MG 13). But the most recent rendition of the saddle magazine, the Betamag, or C-Mag for 100-round 5.56x45mm is attached from the bottom of the gun; their feed boxes emulating the shape of the standard AR-15/M16 or HK magazines.

Another variation of the drum magazine is the spiral magazine, which is kind of a stretched drum. The cartridges are placed along the helical path, but the rows are not wrapped one around another, like in a classical drum, but one in front of the other. This gives the extended capacity, without increasing the diameter of the drum. This could of course be so only with short, pistol rounds, and that’s why it is used mainly with submachine guns. The first spiral drum was designed for the American Calico 900 submachine gun, and the most recent rendition is the Russian magazine for the Krinkov-based Bizon-2 submachine gun.

Pannier Magazines

The last of the magazine design groups are the pannier (or disc) magazines. In these magazines the cartridges are laying flat on their side, bullets to the center, parallel to the bore. These may be set in one (Soviet DP LMG, Lewis 47 round) or multiple layers (Soviet DT tank machine gun or Lewis 96 round aerial), can have their own propelling spring (DP) or be rotated by the gun (Lewis). Most of the drums utilizes the force of gravity for presenting the cartridges at the lips and is placed on top of the weapon, but for the Soviet RPK 74 a prototype 100-round pannier was proposed, feeding cartridges from the bottom, and using the standard magazine well of the AK-weapons family.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V9N1 (October 2005) |