By Michael Heidler

Successful inventors often have to think outside the box. In weapons technology, too, many a smirked-at pipe dream has turned out to be a great success. But now and then it’s difficult to distinguish deliberate charlatanry from actual conviction. This is a problem that the SS-Waffenamt also had to contend with when so-called “inventors” described their ideas in grandiose terms. Like Dr. Christian Fuchs, for example, with his centrifugal machine gun.

Machine guns became an indispensable weapon in warfare. Their firepower helped both in attack and defense. On days of heavy fighting, however, this turned into hard work for the ammunition carriers, considering that a German MG34 could easily fire 800 rounds per minute. The MG42 even managed 1,500 rounds in the same amount of time.

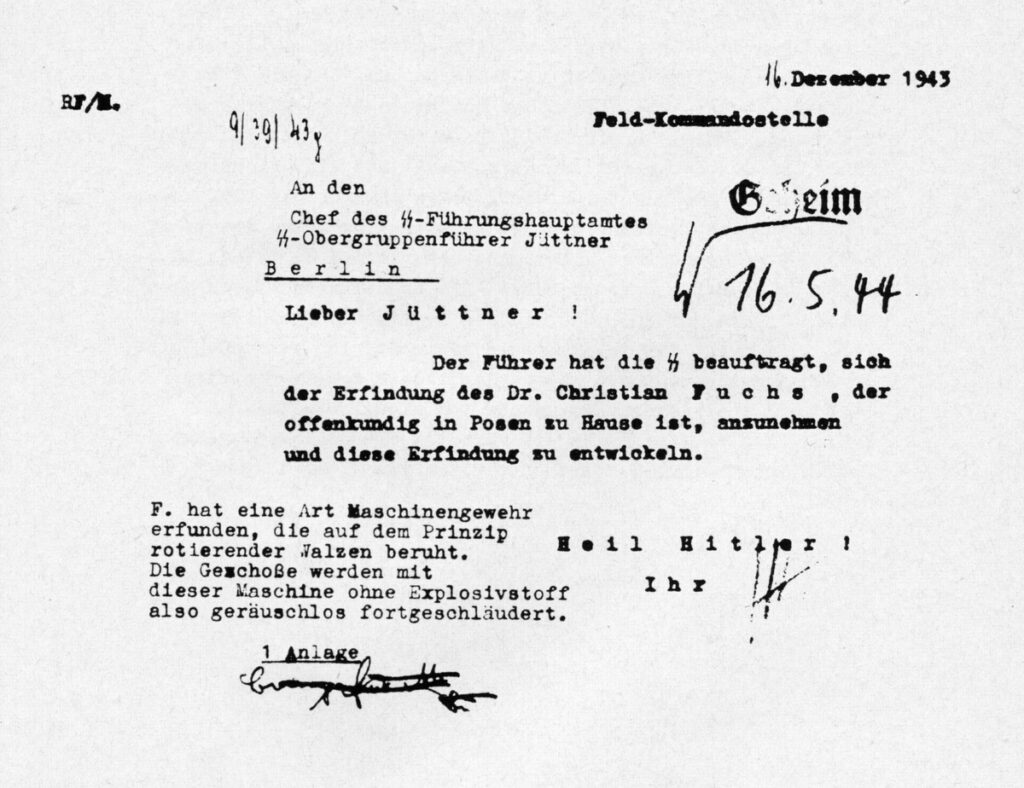

Dr. Fuchs, from Poznań in the Nazi-occupied Reichsgau Wartheland area of Poland, who had a doctorate in law, had the idea of developing a machine gun that used kinetic energy instead of gunpowder to impart thrust to projectiles. Whether he was aware of other prior attempts to create such a device is unknown. He approached the Heereswaffenamt (Army Ordnance Office) with this idea and on 8 February 1943 his project was discussed during a weapons demonstration at the proving ground Kummersdorf as the agenda item “Development of a new machine gun with mechanical projectile acceleration.” According to Dr. Fuchs, his invention was recognized as correct in principle, but the development time needed to create a weapon suitable for frontline use was judged to be too long and he was refused further support.

However, Dr. Fuchs did not give up that quickly. He contacted a Nazi SS office in Poznań and presented his idea there on 20 November. “With this machine, the projectiles are hurled away without explosives, i.e. silently,” it was reported, and that, “Dr. Fuchs has already achieved a performance of 50 shots per second, that is 3,000 shots per minute, with his model.” Furthermore, he lambasted the lack of support from the Speer Ministry, declaring that he needed only six months to complete a weapon “which could be used immediately at the front,” but, of course, only if qualified mechanics and raw materials were made available to him. Furthermore, Dr. Fuchs urged a quick decision, because the suspension period for the public announcement of his patent would soon end and failing to gain an extension would be contrary to the interest of national defense. He urgently requested the support of Gauleiter SS-Obergruppenführer Arthur Greiser and wanted to demonstrate the invention to him personally.

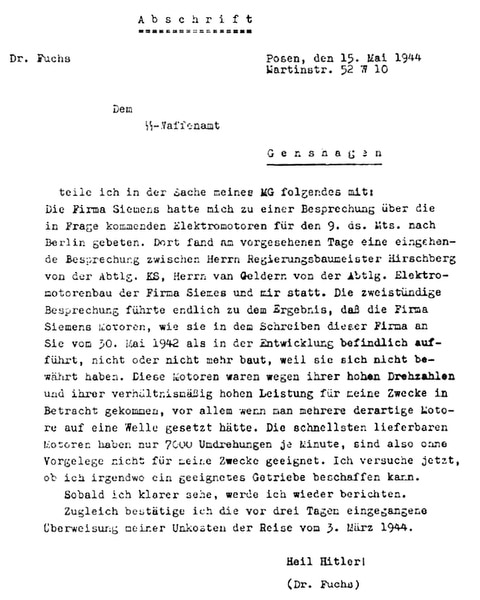

Despite the support of the SS, Dr. Fuchs was unable to procure the necessary high-speed motors and other individual parts. In May 1944, he travelled specially to the Siemens company in Berlin where he learned the compact, high-speed electric motors he had planned to use in his design were no longer being built. Instead, he had to make do with motors that provided only 7,000 revolutions per minute, for which, however, a gearbox was necessary. Siemens agreed “in the most obliging manner” to produce a model of the machine gun and also commissioned the development of a gearbox that ran in oil. But nothing came of it.

In June 1944, Dr. Fuchs wrote to the SS headquarters (Technical Office VIII FEP), “Due to the two heavy air raids on Poznań, the workshops of the company entrusted with the construction of the gearbox were partly destroyed. […] In addition, the manager of the Poznań workshop of the Siemens company has collapsed due to work overload and is therefore no longer able to provide the kindly promised help in the construction of the machine gun.” Dr. Fuchs then built a prototype gearbox himself that reached a speed of 15,000 rpm. On the finished weapon, one bullet would have left the barrel for every revolution.

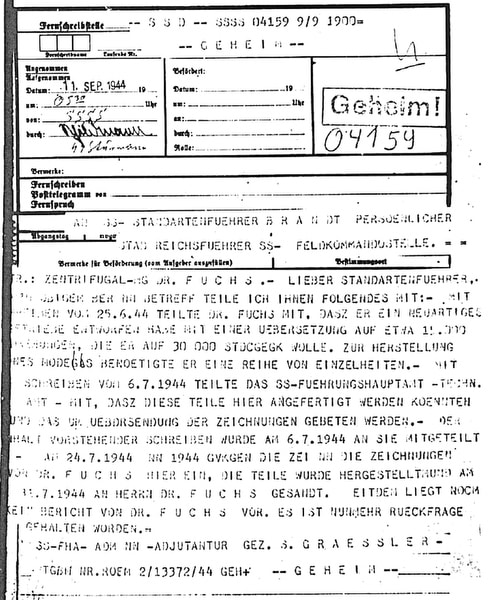

Dr. Fuchs felt very important. He again pressed for help from the SS, who this time were to make certain parts for him. The work would only progress so slowly and Fuchs urged, “since I must not neglect my professional duties as a judge, nor can I cease my intensive collaboration as Hauptsturmführer of the SA, lest I betray the cause. […] Without the requested help, it would hardly be possible to make the new weapon operational for this war. In my opinion, however, that would not be in the Führer’s interests”. Two weeks later, the SS-Führungshauptamt agreed to have the parts manufactured in SS workshops and asked for drawings to be sent to them. In mid-July, the finished parts were sent to Dr. Fuchs.

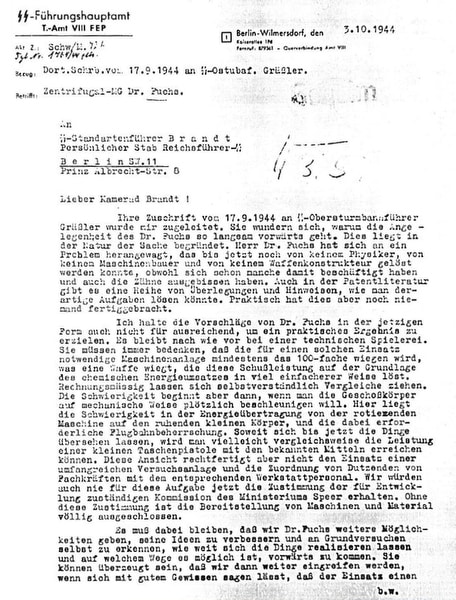

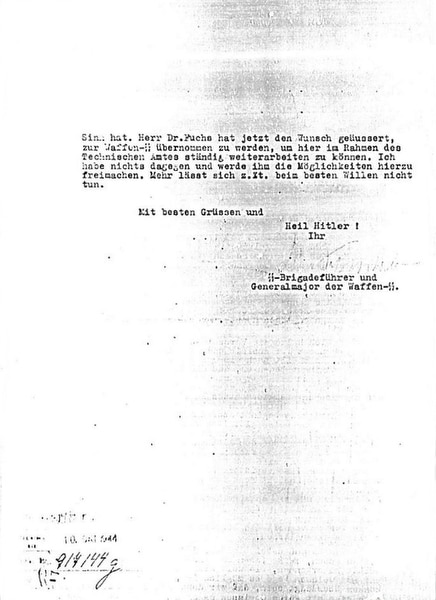

Now the personal staff of the Reichsführer-SS also intervened. SS-Obersturmbannführer Gräßler wanted to know why the matter was taking so long. The head of the technical office, SS-Brigadeführer Schwab, himself a doctor of engineering, made it clear in his answer of 3 October 1944 what he thought of the centrifugal machine gun. He reportedly said the invention was a technical gimmick and that such a weapon would weigh 100 times more than a normal machine gun and the trajectory would be uncontrollable. All this did not justify the use of an extensive test facility and the assignment of dozens of experts, he continued. Presumably in order not to upset anyone, he added, “It must remain the case that we give Dr. Fuchs further opportunities to improve his ideas and to see for himself on basic tests how far things can be realized. […] Dr. Fuchs has now expressed the wish to be transferred to the Waffen-SS in order to be able to continue working here within the framework of the Technical Office. I have no objection to this and will clear the way for him to do so. With the best will in the world, that is all that can be done at the moment.”

Unfortunately, this is where the story ends. The further fate of Dr. Fuchs, the whereabouts of his prototype and the technical drawings of his design are unknown. But, based on what we know of his ambition, the ammunition consumption of his invention would have been incredibly high, if the system worked at all. With some basic math we can see how absurdly the idea was likely viewed at the time. The common heavy pointed bullet (schweres Spitzgeschoss) of the rifle cartridge weighed 12.8 grams. At the intended target of 30,000 revolutions per minute, the centrifugal machine gun would thus have hurled 384 kilograms (about 85 pounds) of lead per minute at the enemy. So, assuming the technology could be developed to realize Fuchs’ design, the weapons insatiable appetite for ammunition would have precluded it from ever becoming a reality given that ammunition was already in short supply in almost every corner of the German Reich by this point of the war.