By Frank Iannamico

Eugene G. Reising began designing his submachine gun in the late 1930s as the threat of war loomed in Europe. Reising’s design was unlike most submachine guns of the day, which utilized the simple, but efficient open bolt method of operation. Reising’s weapon used a delayed blow back principle much like that of semi-automatic pistols. The design allowed his weapon to be lighter in weight, and more accurate in the single shot mode than any existing submachine gun of the period.

After his design was refined, Eugene Reising entered into an agreement with Harrington & Richardson Arms Inc. in 1939. It was agreed that H&R Inc. would manufacture and market Reising’s submachine gun. Reising was to receive a $2.00 royalty fee for each of his submachine guns that were sold. The market targeted was military and police sales. Early H&R literature describing the Reising often compared it to a heavier and much more expensive submachine gun that was available. Although the Reising brochures never mention the “other” submachine gun by name, they were referring to the Thompson Submachine Gun. The low price of the Reising attracted the attention of many police departments. After WWII began the Auto Ordnance Company committed all of their Thompson production to the military, and the Reising became the only option for any police department that wished to add a submachine gun to their arsenal. Federal Laboratories of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was the main distributor of the Reising submachine gun, and its accessories for police sales.

One of the first attempts to sell the Reising submachine gun for use in a military application was to the British in August of 1940. The British were already at war with Germany and were desperate for small arms, fearing that a land invasion by the Germans was imminent The first British tests of the .45 caliber Reising M50 resulted in the rejection of the weapon. There were a few quality control problems at the factory that resulted in the weapon not performing well. The British testing team also described the weapon’s construction as being “quite crude.”

In 1941 the British grew increasingly desperate for small arms. They decided to retest the Reising, which by this time had undergone further development resulting in a substantially improved, more reliable weapon. The second British trial was moderately successful. Although a few of the Reising weapons were purchased, the British had just finished development of their own submachine gun design, the 9mm Sten. Reising and Harrington & Richardson Inc. also unsuccessfully tried to interest the British in the .30 carbine caliber version of the Reising in 1943. The .30 caliber version of the Reising had competed in the U.S. Ordnance Department’s light rifle trials of 1941.

While the Thompson was the submachine gun of choice for the U.S. Ordnance Department, there were problems. The first problem was the Thompson was expensive to manufacture. The second and more serious problem was that they could not be manufactured in the numbers required for the United States and her allies. During WWII the U.S. Marines were often low on the priority list for new weapons, and often relied on obsolete WWI small arms to get the job done. The Marines had discovered in prior minor actions, the value of the rapid-fire submachine gun, and desperately wanted to procure them for their troops. As a result the Marines adopted the Reising Model 50 as a supplementary submachine gun early in 1942. The weapon proved to be unreliable in the harsh jungle environments that the Marines fought in, and incidents of jamming and severe rusting of the arms were reported from the field. Shortly thereafter the Reising was relegated to rear echelon and guard duty, but did continue in service. Eugene Reising, when asked in a post war interview regarding the reported failure of his weapon, stated that no formal complaints were ever filed by the Marines or the Navy Department, though he knew of some problems. Mr. Reising felt that the troops issued the Reising were not given adequate training with the weapon, although he did confess that parts interchangeability between weapons was a problem contributing to their poor performance. He also stated that there was great emphasis placed on getting the weapons into the field, and there was no time to re-engineer the design or production process to allow for complete interchangeability of parts between the weapons.

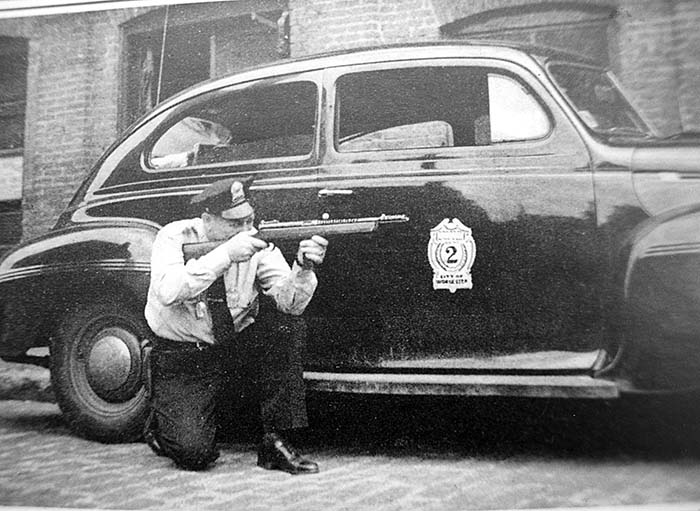

The Reising was also sold to police departments in large numbers both during and after WWII. In the police role the Reising was a very capable weapon. Unfortunately the Reising’s long successful police career is often overshadowed by its marginal performance during its brief military service. The Reising submachine gun was manufactured in several configurations and models by Harrington and Richardson Arms Inc. of Worcester, Mass. This segment focuses on the Model 50.

The Model 50 is fairly well known to collectors and shooters of today, and is often referred to as being either a “military” or a “commercial” model. (The “commercial” model is also known as the “police” model) These nomenclatures of the Reising are often used and accepted today, but are incorrect for several reasons. Harrington and Richardson never advertised or acknowledged any specific “military” or “commercial” model. The Reisings were simply referred to as the “Model 50” regardless of their features. The so-called early “commercial” model eventually evolved into the later “military” configuration. Another reason the “military” and or “commercial” model designation is incorrect is that the military and the police used both configurations. The early models accepted by the Marines were the blue so-called “commercial” models, as were many of the early guns being purchased by the police. After the “commercial” model had fully evolved into the “military” configuration in the fall of 1942, Reisings were pulled from the military production line at random for any police orders that H&R Inc. received.

The early production Reising Model 50s had a polished blue finish and a 28 or 29 fin barrel. Many of the early stocks had no provisions in which to attach a sling. Sling swivels first appeared mounted on the left side of the stock. When the British tested Reisings equipped with the sling attached to the left side of the weapon they complained that it interfered with the shooters weak hand that grasped the forearm of the stock. The designers then moved the sling swivels over to the right side. Installing swivels on the bottom of the stock was not considered at first, because it was felt that the sling would interfere with access to the cocking handle (action bar) which is accessed through the underside of the stock. Most “commercial” model Reisings issued by the Marine Corps had the bottom mounted sling swivels installed. All later production “military” Reisings also had their sling swivels located on the bottom of the stock. Sling swivels were an option on the Reisings sold for police use.

Other features unique to the early “commercial” Reising Model 50 are a stamped 2 screw trigger guard, and a small take down screw that required a tool to loosen. The receiver end cap had a hollow recoil spring guide that was an integral part of the cap. This design proved to be unreliable and the hollow pin was replaced by a solid one. The first major change in the evolution of the Reising was the receiver. The bolt-locking step in early receivers was hardened manually with an acetylene torch. This was automated in the new receiver to make the hardening of this critical area more consistent. Another improvement in the new receiver was the addition of a second locking ball to keep the receiver end cap or “bumper plug” from loosening during firing. The second design receivers are easily recognized by the direction of the logo stamped on the top. Early receivers have the H&R logo stamped so that is readable from the right or ejection port side of the weapon, while later receivers are readable from the left. The new style receiver first appeared in the early 15,000 serial number range.

The contents of this article were excerpted from the new book “The Reising Submachine Gun Story” available from Moose Lake Publishing 207-683-2959 Next: the evolution of the “military” Reising.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V3N12 (September 2000) |