By Terry Edwards

David spun his sling up-to-speed overhead and loosed a stone at Goliath. It hit the giant in the head, killing him and winning the future King of Israel ever-lasting glory. The sling, the first centrifugal force weapon, was a success of Biblical proportions and the high point in its history.

The sling remained a viable weapon and was joined by other projectile weapons: bows, spears, stone throwers and an array of mechanical launchers from handy cross-bows to trebuchets that could hurl a small car. Mankind constantly brought the latest technology to weapons.

Gunpowder changed everything. But, gun powder is noisy, dirty, expensive, delicate, sometimes unreliable and dangerous to have around. All this just to accelerate a projectile to high speed and launch it with precision. Surely we can manage that by machine—we’re still trying.

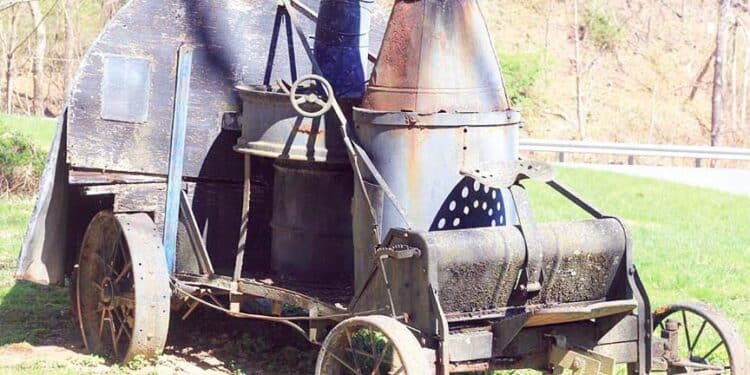

A not quite so high point in history as David is the Winans Steam Gun. It most likely would have faded into the history books except for several history buffs, Mark Handwerk, Joseph H. Clark and Joseph Zoller III, who constructed a full-scale copy for the 1961 Civil War Centennial. Near the sign on U.S. Route 1 proclaiming Elkridge, Maryland, the hulking beast quietly subsides into the soil and mystifies passing motorists.

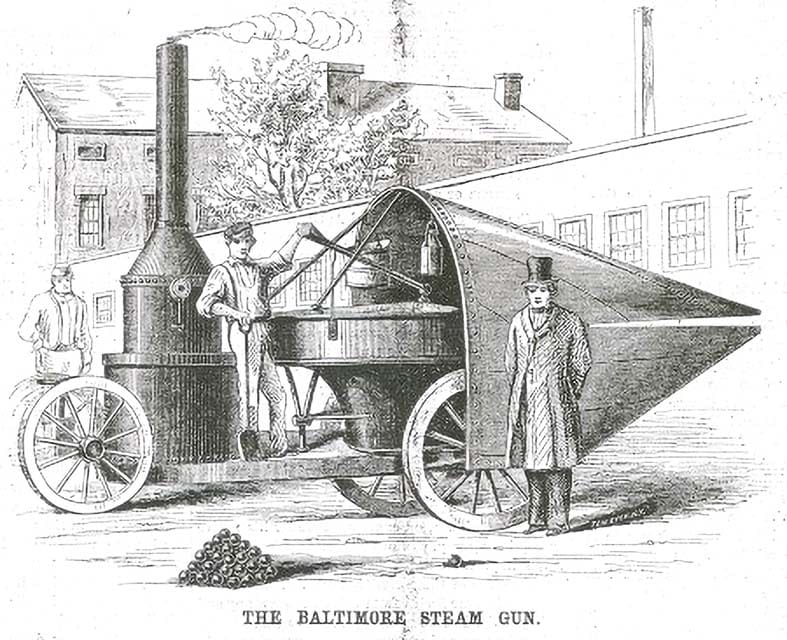

Also known as the Baltimore Steam Gun, the gun is seldom called for its designers, Charles S. Dickinson and his early partner in the project, William Joslin.

The partners produced several manually powered examples of centrifugal weapons but parted ways when the first patent they were issued named Joslin alone as the inventor. Dickinson then polished the design and patented it himself in 1858. He had the gun built in Boston and set out to sell it. In April 1861, the sales tour took him and the gun to Baltimore, Maryland, just in time for the infamous Baltimore riot.

Fort Sumter had surrendered to Confederate forces days before, and the alarmed government in Washington, D.C., was calling in troops to man the Capital’s defenses. Baltimore was politically divided, and many citizens were pro-slavers and Southern-sympathizing Democrats.

No one had died in battle at Fort Sumter: The only deaths were the result of a Union gun explosion during the formal surrender ceremony. Until the Baltimore riot of April 19, no blood had been shed in this “fraternal” conflict.

Baltimore’s decision to not allow steam engines to run through the center of town resulted in two railway stations a mile or so apart—the President St. Station and the Camden St. Station. Railway cars had to be pulled by horses from one station to another before continuing their journeys.

When the men of the 6th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Militia arrived on their way to Washington, they disembarked their train and marched along Pratt Road. Trouble started when hundreds of protesting citizens turned out onto the street. Hurled shouts and vegetables gave way to gunfire, and the troops, civilians and police clashed bloodily. Four soldiers and 12 civilians died. Dozens more were injured. The battle is acknowledged as the first blood spilled in the American Civil War, and it was the point of no return.

In the excited days before the trouble, the City of Baltimore’s leadership had tried to assure the citizens they would be defended against the ever-villainous, Washington, D.C., forces of darkness. In the display of weaponry shown to the public, were pikes made at the factory of Ross Winans, a wealthy local industrialist. Dickinson had taken the gun to the Winans plant to work on it and gladly allowed the city to show it off for him. While Dickinson’s gun did not take part in the battle, it was drafted for defiant display.

The steam gun’s purported power sent the press on a predictable trajectory:

“It can be constructed to discharge missiles of any capacity from an ounce ball to a 25-pound shot, with the force and range equal to the most approved gunpowder projectiles …”

“… the musket caliber engine would mow down opposing troops as the scythe mows down standing grain …”

“… will strike terror to the hearts of opposing forces and render its possessors impregnable …”

Dickinson modestly added, “… its very destructiveness will prove the means and medium of peace.” His pitch is evocative of Gatling’s later claims, and similar words are still later attributed to Hiram Maxim. Whatever … whoever … they were wrong.

It all did not translate to sales for Dickinson. For all the considerable publicity, the gun gained fortune for no one, and the brief flare of fame it garnered didn’t even illuminate Dickinson as the press erroneously dubbed his brainchild “the Winans gun.”

Even the renowned Scientific American muddied the history; saying the gun was built by Ross Winans. The article at least acknowledged the gun was Dickinson’s design.

In the weeks after the riot, the U. S. federal government exerted more and more pressure on the petulant city, arresting pro-Southern politicians and even police officials. Ross Winans was feeling the heat for his pro-Southern leanings.

Dickinson decided to dispatch his gun to Harper’s Ferry and offer it to the Confederacy. Mounted men of the 6th Massachusetts Militia intercepted the gun at Ellicott Mills, Maryland, on May 11. These were some of the same men attacked during the riot.

The gun and crew were seized and the weapon commandeered for United States’ use. Back in Baltimore, Winans was arrested, but released 2 days later after promising to build no more arms for Southern sympathizers. Dickinson, describing the moving of the gun as a dastardly rebel plot, hastily tried to make amends by offering to build the Union an improved model for $10,000. There is no record of President Lincoln responding to the offer.

After testing, the steam gun ended up at the Thomas Viaduct, a railway bridge joining Relay and Elkridge, Maryland, over the Patapsco River.

How It Worked

The gun required at least two horses to move its four-wheeled mount. The steam engine occupied half the vehicle. A firebox generated steam to power the gun. In the initial excitement around the gun, some reporters mistakenly said the engine could propel the vehicle as well. This was not the case. The steam energy was harnessed to rotate the single barrel. This barrel was L-shaped and spun at about 250-rpm. A ball released from the stack in the vertical portion entered the rotating portion and was driven outward by centrifugal force. At the right moment, the muzzle passed by a gate where the round was released. As a safety measure, the barrel spun in a steel drum. This resembles a barrel of another kind, further confusing people. To protect the crew and gun from enemy fire, a funnel-shaped shield was provided. This featured a slit allowing the barrel to be aimed and discharged in the desired direction.

All the centrifugal guns of the era were smooth-bored. Accuracy was abysmal. The stealth afforded by the lack of a loud gunshot was often offset by other factors. There was the issue of keeping the steam pressure ready. The smoke and fire also made concealment difficult, and a supply of fuel had to be carried or scavenged. But, after all this, when the gun was running, it spewed out a fearful stream of balls that were capable of painful, if not always lethal, effect.

It was never called into action and ended up being scrapped after the War.

Myth Busting

The MythBusters television show constructed a steam gun based on the Dickinson design, with a pair of water heaters providing the steam. On their test run, a single round struck the gun’s steel safety shield creating a deep dent which suggested potentially lethal damage to a person. The MythBusters tested the gun at a range of 500 yards and attained a rate of fire of 400 rounds per minute. The gun performed well, firing five rounds per second to a range of 700 yards. However, the weapon lacked lethal force at that range and was not very reliable. The MythBusters concluded the steam gun, as a weapon, was too unreliable and impractical.

Others Enter the Field

The Dickinson/Winans gun was far from the last hurrah of the centrifugal gun. As told in Lincoln and the Tools of War by Robert V. Bruce, the McCarty gun was developed independently and demonstrated in New York. It gave such good results it was sent to the Washington Arsenal. President Lincoln himself arrived to meet the inventor and his friend, Colonel George D. Ramsey, Commandant of the Arsenal. Although an open-minded man, Ramsey was no fan of centrifugal guns. He’d seen attempts fail before and loudly disparaged the concept, the inventor and the gun itself. His contempt threw McCarty off to the point he misadjusted the gun and when the President himself fired it, several rounds bounced backwards to strike spectators’ ankles.

But John A. Dahlgren, of Dahlgren gun fame, was also watching and not so easily put off. He tested McCarty’s device and built a larger version capable of throwing 15, 12-pound rounds a mile away in 16 seconds! Once again, accuracy was terrible and doomed the project.

Another notable attempt was described in the Baton Rouge Advocate in 1861. Henry Cowing’s design was an adaption of a road-worthy steam locomotive equipped with a steam-air cannon. The gun was silent, smokeless and could be dismounted to restore the locomotive to other tasks. The device was arguably an early self-propelled gun, or, if equipped with armor, an advanced early tank. Unfortunately, little else has been recorded about it.

The 1862 horse-drawn armored Land Monitor reportedly began construction in Leavenworth, Kansas. It was meant to fire 5,000 rounds at 600 rpm. It did, however, weigh 25,000 pounds.

According to Scientific American, Dr. Draper Stone demonstrated his centrifugal steam gun at the La Cross Roundhouse in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. While the May 1861 demonstration was judged a success, his project got no further mention.

Scientific American recorded an even earlier centrifugal gun designed by Benjamin Reynolds of Kinderhook, New York. When tested at West Point in 1837, it fired 1,000 rpm of 2-ounce balls able to penetrate 3.5 inches of hard pine! Similar results were shown to Congressmen and notaries at a demonstration in Washington. The project then faded from view.

WWI

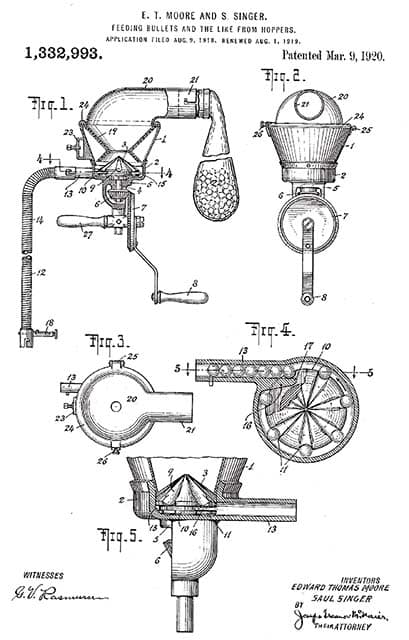

The centrifugal gun came up yet again in WWI. Edward T. Moore was granted patent #1332992 for his silent electric machine gun. Moore replaced the L-shaped barrel of Dickinson’s design with a grooved rotating disc. Moore’s weapon dropped rounds onto the disc which whirled them up to speed and spewed them out with a disconcerting lack of accuracy.

Still, the idea had such appeal, another First World War attempt was made using an aircraft engine for energy. E.L. Rice proposed it, and the idea was vigorously pursued by the American National Research Council. As in other attempts, the apparent simplicity of the idea proved deceptive, and technical problems eventually frustrated the effort.

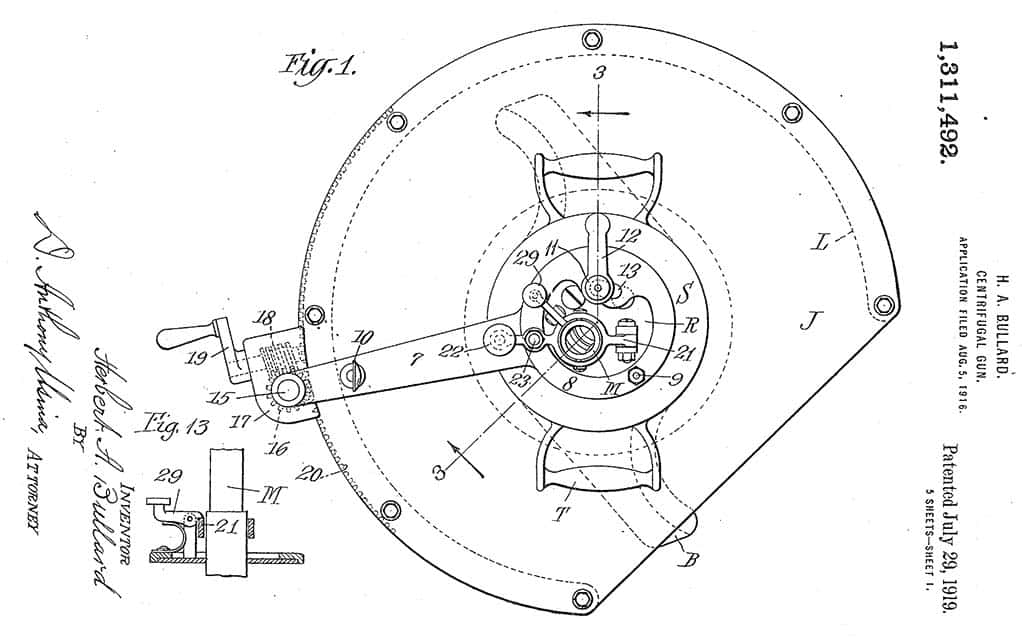

A further WWI patent is #1311492 from Herbert A. Bullard. His design departed from all the others by firing a disc rather than a ball. He used a rotating arm with launching points on both ends. This was driven to high speed and fed with a series of disc projectiles.

The DREAD System

Around the turn of the millennium, Charles W. St. George, the Australian designer of the Leader T2 MK 5, applied his talents to develop the DREAD™ system. A slick video on YouTube touts the weapon’s major advantages. The ammunition consists of balls, capable of carrying explosives, chemicals or whatever the user chooses. The feed system regulates the fire rate by timing the release of the ball-bearing projectiles.

Because combustible propellant is not used, the ammunition is safe and easy to store. Pistol-like velocities are cited but the rate of fire is stated to reach 240,000 rpm. Where automatic rifle bullets are spaced out roughly 100 feet apart, the DREAD projectiles can be launched about one third of an inch apart! The weight delivered to the target is huge; almost a solid projectile of whatever length the user chooses. The promotional material emphasizes the stealth aspect of the weapon as the usual weapon signatures of flash and noise are all but eliminated. In addition, the negligible recoil allows for easy aim and a light mounting. The developers show the weapon in use on land, sea, air and space.

A number of firms and partners entered the development at various times, but although at least one prototype was apparently produced, the project never came to fruition and is no longer being pursued. The promotional video remains on YouTube of the DREAD and an interview with St. George is on Forgotten Weapons.

St. George eventually lost interest and moved on to work on the M17 bullpup 5.56mm rifle and the .50-cal version. His earlier Leader T2 MK 5 rifle saw limited production, and roughly 2,000 examples were landed in the U.S. before laws ended the importation.

Current Projects

At the moment, the gunpowder-powered, bullet-firing gun, has no competition. But, there is no reason to think the interest in centrifugal weapons will fade away. It is one of the few alternative ways to achieve lethal velocity in a portable device. Technology improves daily, and the problem of accuracy that bedevils centrifugal weapons may well be solved. Meanwhile, other technologies are meeting the desire for stealthy, flashless, noiseless and smokeless weapons. The U.S. Navy will soon deploy an electric ship’s “cannon” using electrically charged magnetic rails to accelerate projectiles.

Finally, in 1963, Popular Mechanics published plans for construction of an electric miniature centrifugal gun. Materials and technical skills would seem in reach of most teens. Designer Roy L. Clough, Jr., claims the semiautomatic fires BBs at a velocity of 25 fps.

• • •

Thanks to James Samalea, Carol Mintoff, Popular Mechanics, John W. Lamb, author of Strange Engine of War; Chesapeake Book Company, Roy L. Clough, Jr., Charles W. St. George, Trinamic LLC, and Movie Armaments Group.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V23N10 (Dec 2019) |