By George E. Kontis, PE

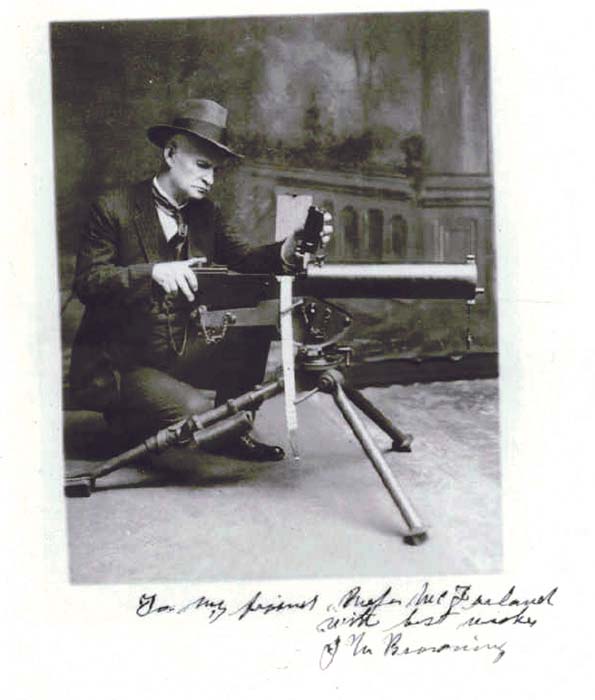

Early Browning

John Moses Browning was the greatest firearms designer in the history of the world. A man with a unique design philosophy whose products were sleek, effective, and reliable. He had a storied career, but faced many of the same challenges we do in the small arms industry today. Examining his history offers us an effective insight to the path forward.

Born in 1855, John—or Jack as he preferred to be called, was a member of a large Mormon family. His father was a gun designer, gunsmith, and blacksmith who built and repaired firearms on the Utah frontier. Little Jack loved playing in his father‘s scrap pile. The parts and pieces he found were used to build toys—mostly guns. Jack had a keen eye for detail. Through examination of failed gun parts found in the scrap pile, Jack received an early education on the weaknesses in gun design. These were important lessons which became useful to him in his later years.

One day, when Jack was a teenager, he found himself in a barn with his family and friends. They had harvested apples that day and the group’s chore was to peel them. It was tedious and boring. By noon, Jack had enough. He slipped a few apples in his bag and headed for home, or to be more accurate, his father’s blacksmith shop next door. Just after lunch, Jack showed back up at the barn carrying an odd looking contraption. He sat it on a table, loaded an apple onto it and proceeded to turn a hand crank. The device peeled the apple then removed the core when it was done. This was the mark of John M. Browning. He could visualize, design, build, test, and deliver faster than anybody.

John and his father both made attempts to design a repeating rifle. The task was complicated by the fact that both rifles were muzzle loaders. John’s father admitted that his son’s design was better than his, but both agreed neither one was all that great. There was no easy way to rapidly create all the motions required for muzzle loading. Unfortunately, it did not lend itself to repeater fire. During and immediately after the Civil War, the brass cartridge case began making a huge headway out on the frontier. With the brass cartridge, the floodgates opened for John Browning designs. Years later, John commented on how the brass-cased cartridge created the opportunity for new designs saying, “It was the right time and the right place for a gun maker and I just happened along.”

Winchester and the FN Connection

John’s first cartridge gun was a single shot rifle. He tried to mass produce it in his now-departed father’s gun shop using his many brothers as laborers. The group didn’t have the right tools or production manufacturing knowledge, so it wasn’t long before they faced late delivery problems. Just then, Winchester happened along. They had heard about his rifle and came looking for it. Full design rights were sold for a mere $8,000. Even though his later designs were sold for to Winchester and others for far more, John always regarded it as his best sale ever. This first design began the Winchester relationship, paying him cash for everything he designed. During his 17-year association with Winchester, he would go on to design 44 models for them. Design, test, negotiate, deliver became a game. He would travel out to Winchester to present his latest creation—completely designed, built and fully tested. He and Winchester would settle on a price and then discuss John’s next design project. At the beginning of their relationship, John would promise a design time of around six months to deliver his next prototype. As he got more adept at design, he would promise Winchester shorter and shorter development times. He never failed to deliver on schedule. Once, he delivered his next tested prototype in a mere two months.

In Browning’s 47-year career, he was awarded 128 patents, more than all other firearms designers during that time period. After learning about Fabrique Nationale (FN), a factory in Belgium making Mauser rifles under contract to the Belgium Government, Browning established a relationship with them to build the Hi-Power pistol, and other designs.

Browning’s Military Weapons

One day, while doing some prone shooting, John notice the grass out in front of the gun was moving with each shot. Could gun gas be harnessed as an energy source for a fully automatic rifle? John told his brothers his ideas for making a machine gun. They were excited at first, but the excitement died rapidly when John said it would be a 10 year undertaking. That was in 1889. One year later, youngest brother Matthew Browning—the best writer in the group—penned a letter to Colt. “We have just completed our new automatic machine gun & thought we would write to you to see if you are interested in that kind of gun.”

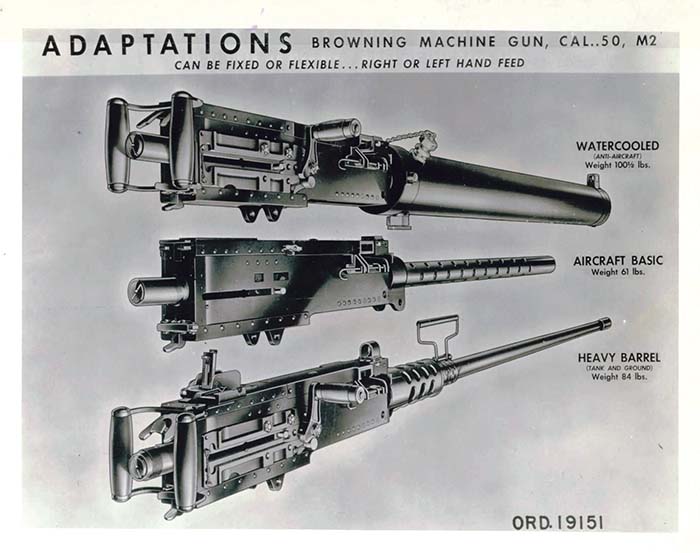

Browning turned the profitable sporting goods and outfitter business over to his brothers in order to concentrate on guns for the U.S. military. The military heralded him as a great patriot for accepting a lump—sum $1.5 million dollar payment for his designs in lieu of royalty fees worth many millions. The Military weapons he developed included the M1895 Colt Machine Gun (The “Potato Digger”), M1919 .30 cal. Machine gun, Browning Automatic Rifle, 37 mm aircraft cannon, M2922 pistol, and the M2 .50 caliber machine gun. The latter two are still in use today.

Lessons in Lethality

It’s important to note neither John Browning nor his many brothers were ever in combat. Their experience was totally in hunting firearms and they were plenty savvy on that topic. Ammunition was scarce out on the frontier, and it was important to make one shot for one kill on the deer, bear other large game. Varmints were common targets as well, since they could wreak havoc on domestic farm animals and crops.

For large game, in particular deer, one of Browning’s guns became the gold standard. The Model 94 Winchester chambered for the .30-.30 cartridge was lightweight yet extremely effective. Firing a huge bullet at high velocity developed more than sufficient energy to drop a deer in its tracks even if it wasn’t a particularly clean shot. After millions were sold over more than half a century, Winchester’s 1972 advertisements claimed the Model 94 chambered in .30-.30 Winchester was responsible for killing more deer than any other rifle in the history of the world.

5.56mm as a Combat Round

While today there are powerful alternatives, the .30-30 cartridge is still widely used as an effective caliber for deer—a crafty mammal weighing on average 150 lbs. Varmint shooters continue to use the .22 caliber rimfire on the smaller crows and rats, while other calibers like the .223 Remington (5.56mm) are more effective on larger varmints, like the wily coyote. The average weight of the coyote is 46 pounds.

With these calibers and targets in mind, we now consider the current threat- the Middle Eastern Terrorist. On average, he weighs in at 170 pounds. Knowing what we’ve learned through the years about one-shot-one kill on 150 pound animals, how can we justify using a puny 5.56mm cartridge on a 170 pound adversary? On large mammals, like the deer, the 5.56mm is recognized as a wounding round, not a killing round and is outlawed in many states as a consequence. What is the smallest, most effective caliber for deer hunting? Knowledgeable deer hunters and sports writers will tell you with a certainty backed by years of experience. The smallest, effective, deer calibers are the .243 Winchester and other 6 mm to 6.5mm cartridges.

In March 2016, LTC Troy Denomy, briefed the Small Arms Community at the annual meeting of the National Armaments Consortium. A decorated hero, LTC Denomy led combined infantry and motorized troops into an 88-day battle in Sadr City, Iraq. “What was the effectiveness of our ammunition”, we asked him? “Well”, he replied “when you hit a guy with one round of 7.62mm NATO he went down. If you were shooting 5.56mm it always took at least two hits to drop him.” This observation is commonly heard from experienced US Forces.

A Browning Critique on Today’s Combat Rifles

If Mr. Browning were here with us today, he might have a few thoughts for us in relation to our gun designs. For example, the automobile and the modern cartridge rifle are approximately the same age. Through the years, when automobile makers would observe car owners adding accessories, like radios, air conditioners, power receptacles, it was not long before these were incorporated into the vehicle design. Not so with the rifle.

Yes, we have mounting rails for optics, lasers, and flashlights, but nothing is ever incorporated into the weapon itself. It is certainly not beyond our technical capability to add some needed devices. Take a firearm “odometer” for example. A simple, on board, round counter would give armorers an ability to evaluate their weapons, removing or repairing those with excessive round counts.

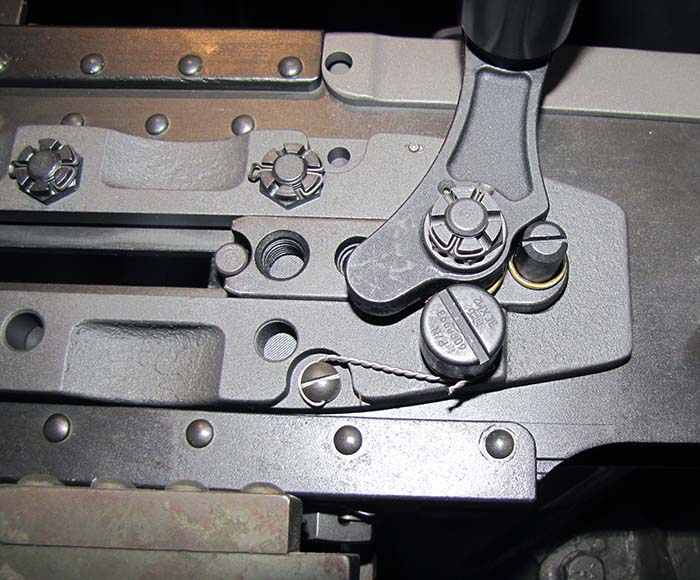

Something else to catch Browning’s critical eye would be our excessive use of threaded fasteners. Even in Browning’s day, gun designers knew threaded fasteners have limitations. They should be used sparingly—if at all. A threaded joint might seem tight after being made secure, but during firing a high speed shock wave travels through the weapon, causing the threads to rock against each other. This often results in loosening and sometimes affects accuracy. Unless threaded fasteners are mechanically secured with locking wire or other means, many of them will vibrate loose and fall out.

Some designers can’t be bothered with mechanical retainers. Instead they call upon thread locking compounds. To be effective this sticky goop must be applied to clean, degreased threads and care must be taken to avoid overflow into other areas on the weapon where it might gum up the works. Once applied, it’s near impossible for a Quality Inspector to verify all threads have been pre-treated properly and compound applied. These compounds have a shelf life, complicating their use in remote locations. Did a few threads miss being treated after the assembler took a break? Chances are the warfighter will find out at just the wrong time.

Is it too much of a challenge for firearms designers to design their way around threaded fasteners? It wasn’t for the three brothers at the Mauser factory. In the late 1800’s they designed what is now designated the M1896 Mauser Pistol—often called the “Broomhandle” from the shape of its grips. This highly accurate pistol has interlocking components and can be disassembled with no tools. A single screw secures the wooden grips to the frame. The grip screw was the only one they couldn’t design their way around!

When Browning sailed for Belgium on one of his many trips to work with FN, he left the “inch” world and entered the “metric” world. It is very likely Browning found the metric system much more logical and simpler, as do many of us who have worked in both systems. Practically every country in the world has converted to the metric system, yet we staunchly stand by our archaic system of measurement. Stocks of inch system fasteners and tools—like torque wrenches, are not easily found abroad, causing American made guns to be less desirable on foreign markets. American firearm manufactures have been slow to realize this.

U.S. Combat Weapon Programs

Since World War II, we have tried very hard to come up with new combat rifle systems. In 1951 we had the SALVO system where we experimented with multiple projectiles to increase hit probability. This failed and we went on to the Special Purpose Individual Weapon (SPIW) program where high speed flechettes were fired with the intent to use speed to increase impact energy. The flechettes were very inaccurate so the SPIW program failed too. On the Advanced Combat Rifle (ACR) program we tried caseless rounds, case telescoped ammunition, conventional ammunition and again flechettes in combination with efforts to combat soldier stress during combat. You would think, after that didn’t work, we would stop and wonder what we’d been doing wrong for the last 40 years, but that didn’t happen either.

John Browning credited his success in firearms development with having a fully developed cartridge to work with. All along, we’ve been trying to develop ammunition and projectile launcher together and we have always gotten ourselves into trouble. Suppose we had spent the early years of these projects concentrating solely on the development of a new round of ammunition? We could have started with Mann barrels to prove out the accuracy and to provide us with internal ballistic characteristics. After we were happy with results, we could have followed with more and more complex test fixtures designed to test out automatic firing, barrel wear, hot environments, cold environments, sand, dust and other adverse conditions found in combat. When we were sure we had a reliable ammunition capable of withstanding the rigors of combat, we could then have given it out to the small arms industry, challenging them to develop a lightweight rifle with all the characteristics we need. Sounds simple, but that’s what worked for Browning and it probably would have worked for us too. Even if no new gun emerged, it would have saved us a lot of time and money in the long run.

The Elusive Grenade Launcher

In 1990 we again got ourselves in trouble with ammunition, but this time in a different way. The design objective for the XM25 grenade launcher was to fire a grenade programmed to detonate at the enemy’s location. The XM8 was the onboard backup rifle for use if the grenade supply ran out. The combination XM25 married to the XM8 rifle was designated XM29. Unfortunately, it was already a difficult challenge to make a grenade detonate at a prescribed distance from the launcher. It was even more of a challenge to come up with a grenade cartridge large enough to have significant lethality, yet small enough to be light and portable. Again, a series of test fixtures would have speeded the development time.

Adding the 5.56mm XM8 was a non-starter from the outset. Why? Several of the competitors planned the addition of a tiny yet lethal short range anti-personnel cartridge, were faced with a new roadblock. One of the services demanded the XM8 fire the much-larger 5.56mm NATO round and threatened to withdraw their money and support if their demands were not met. Now it was certain. The already large XM25 launcher would be married to the “also large for the purpose” XM8 to become the XM29. A marriage made in heaven. Hog heaven that is, thanks to the bulk and weight of the pair.

Will the XM29 ever be fielded? In March 2016, the Army announced the grenade portion, XM25, might be fielded the following year. If it happens, it will mark 27 years since program inception. No one talks much about the eventual marriage of the XM8 to complete the XM29 design.

“No man gets an idea at first that amounts to much, and that it is only by the most persistent efforts that an invention is perfected.” -John M. Browning

Enhanced Carbine and the M855A1

In 2008 we began the Enhanced Carbine program and sure enough we let ammunition get the better of us again. This time the ammunition was an Army development. Interior ballistic characteristics were known for the M855A1 and a supply of ammunition was built. The Army refused to let the gun making industry have test ammunition or even let them know the ballistic characteristics in order for them to properly design a gun. Instead, they offered them an opportunity to test the ammunition at the H.P. White Laboratory. Each interested gun maker was required to bring guns and all test equipment to this location at their own expense. The new ammunition cracked bolts and wore out barrels, frustrating the competitors to the point some dropped out, envying the smarter ones who didn’t participate at all. Like all the others, the Enhanced Carbine program came to a grinding halt. With no program, all the competitors lost money, one manufacturer reporting he had spent a quarter of a million dollars on the effort.

What’s in our future?

The military is already making rumbling noises about dropping the 5.56mm round in favor of something more lethal. If we are to move away from the legacy of 5.56mm ammunition and the huge stockpiles of both guns and ammunition, we’re going to need an entirely new round. Will it be a brass cased 6.5mm cartridge? Highly unlikely, simply because making a larger conventional cartridge gets us the lethality we need but at the expense of added weight. Added weight is a direct opposite to our agreed direction for the future. What could be of interest is a lightweight cartridge around 6.5mm weighing less than the current 5.56mm round. The LSAT machine gun is being developed to use 6.5 mm case telescoped ammunition. Is this the answer? It certainly will yield greater lethality with less weight! Browning attributed his success to an entirely new round. Would it work for us too?

Give us the Ray Gun

New technologies were a boon to Browning. In his time, muzzle loading ammunition gave way to brass cased cartridges, black powder to smokeless powder, and cast iron yielded to much more performant steel alloys. Browning saw technology move fast and so have we. With that in mind, how do you imagine the gun of the future? Likely it will not fire bullets, or at least the kind we are familiar with. It could fire a laser or some other means of directed energy. It will still have to be man portable and will need to offer a level of hit probability and lethality much higher than our present systems.

In 1995, the Army invited small arms manufacturers to a meeting to discuss the next Personal Defense Weapon, or PDW. They warned us ahead of time that it didn’t have to launch bullets and it didn’t even have to be lethal. There were new technologies around and they wanted to explore them with us. Many of the Government Labs like Oak Ridge and Lawrence Livermore were there to discuss this next killing or disabling mechanism. Speaker after speaker explained their PDW concept, yet no one could say their technology was anywhere near ready for development into a man-portable weapon. The meeting ended and no new technology was identified to replace the rifle or pistol, neither lethal nor non-lethal. However, there was an interesting conclusion offered at the end of the meeting. The Government labs were in agreement. By the year 2010 they would be able to identify a new PDW technology. We are long past that deadline and at this point there could be even newer technologies ready to exploit. If we are going to stay ahead of the competition, it’s time we have that meeting again.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V20N7 (September 2016) |