By James L. Ballou

The K-Ships:

In 1942 and 1943, German U-Boats lurked off the east coast of the United States and the Florida Straits; a particularly fertile hunting ground for Nazi submarines. As America was caught relatively unprepared for war in December 1941, there were few resources available to defend America’s coastlines.

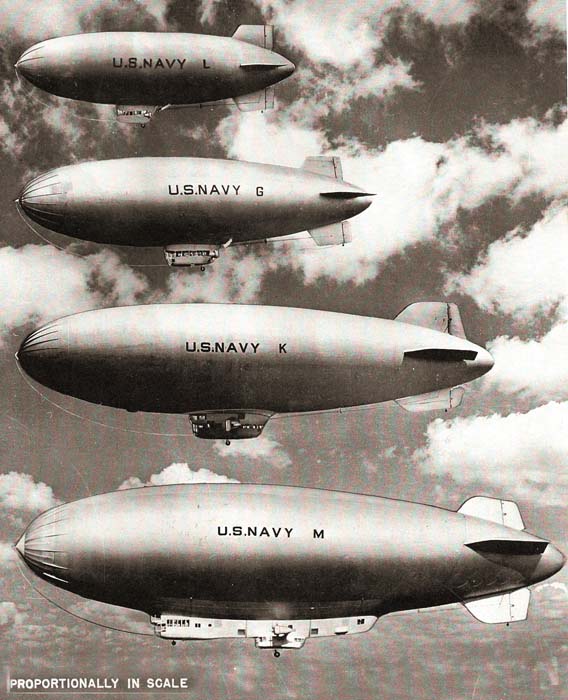

During this time the U.S. Navy employed lighter-than-air, non-rigid airships or “Blimps” to serve as hovering observation platforms for maritime reconnaissance and also to provide escorts for the vital convoys and coastal shipping. The silvery Blimps, called “K-ships” by the Navy, were very stable platforms but they were also quite slow and presented a huge target. They were not considered to be combat aircraft per se, but for their duties of convoy escort and anti-submarine warfare, they were armed with depth bombs and a .50 caliber machine gun mounted in the nose of the gondola car.

Blimp patrols were generally long and uneventful, but there was one remarkable incident that may have influenced the idea to create BAR mounts specially devised for blimps.

On the night of July 18, 1943, the U.S. Navy Blimp K-74 (from Blimp Squadron ZP-21 based at NAS Richmond, Florida) was engaged in convoy escort duties over the Florida Straits and with her onboard radar located a German U-Boat running on the surface. As no American surface units were available to engage the enemy and the U-Boat was proceeding directly towards the convoy she was escorting, K-74 attacked U-134.

K-74’s depth bombs failed to release, and the crew engaged the sub with their .50 caliber machine gun as well as small arms. Return fire from the U-Boat’s 20mm AA guns knocked out one of K-74’s engines, punctured the gasbag in several places and wounded one crewman.

In return, K-74’s fire damaged the submarine and it was not able to submerge. U-134 left the area, and was recalled to its base in France due to its need for repairs. The sub never made it home and was sunk by British bombers in the Bay of Biscay.

As for K-74, the damaged blimp crashed into the sea. While the crew was in the water waiting to be rescued by the U.S. Navy destroyer Dahlgren, tragedy struck when a wounded crewman was attacked by sharks and disappeared. The rest of the crew were rescued, and thus ended the only known gun battle involving a U.S. Navy Blimp.

Although the photos of the BAR blimp-mounted gun found in U.S. Navy files were dated October 1943 (unfortunately they were uncaptioned and offered no details about the project), there is no way to know for sure if this experimental mounting was conceived before or after the incident with K-74. It is possible that the blimp-mounted BAR concept came prior to K-74’s gunfight with U-134, but testing was accelerated after the blimp’s combat with the sub.

The mounting of a .50 caliber Browning machine gun in the gondola car makes more sense than the BAR due to the long range and striking power of the .50 caliber rounds and the nature of the blimp’s escort missions. However, the cramped conditions of the gondola car make the BAR a better option than anything else in the Navy arsenal, particularly as supplemental firepower to the .50 caliber nose gun. If K-74 had possessed two socket-mounted BARs in addition to its .50 caliber on that fateful night, the situation might have been different, but once the Germans opened fire with their 20mm AA guns the issue was never really in doubt.

The assessment that the BAR would have likely been used aboard a blimp to engage floating sea mines, and explode (or sink) them from a safe distance from a relatively stable aerial shooting platform is entirely plausible.

From its adoption in 1917 for the use in the trenches of France to the M240 GPMG in the sands of Iraq, John M. Browning’s superb BAR action has served this country in myriad and strange ways.

What started as an automatic rifle to clear trenches in World War I, it continued to serve in World War II and Korea as a Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW). In numerous and bloody battles all over the globe it has been respected and cherished by our fighting men. In the 1950s the BAR evolved into the “ideal belt fed” GPMG, the M240 Series.

It came as no surprise that the BAR could be used in an antiaircraft mode but it was also used in aircraft for defense. But, by far the most unusual use for the BAR was by the United States Navy when it was mounted in lighter than air crafts, commonly called Blimps.

The 1937 Hindenburg disaster pretty much doomed the lighter than air craft as a weapon of War. The USA avoided the problem as they used and had an unlimited supply of the inert helium gas.

After the tragic loss of the Dirigibles Akron and Shenandoah, Lakehurst, NJ began to concentrate on the non-rigid aircraft, thus the use of the Blimp as the primary lighter-than-air craft. Thus began the most successful implementation of blimps for air defense. In 1939 they developed the K-Craft blimp and it became the workhorse of World War II that could patrol and destroy the U-boats with bombs, torpedoes and machine guns. Able to fly cover for convoys, Navy blimps could patrol for weeks at a time and hover over suspected targets and were high enough for excellent radio relay and interception.

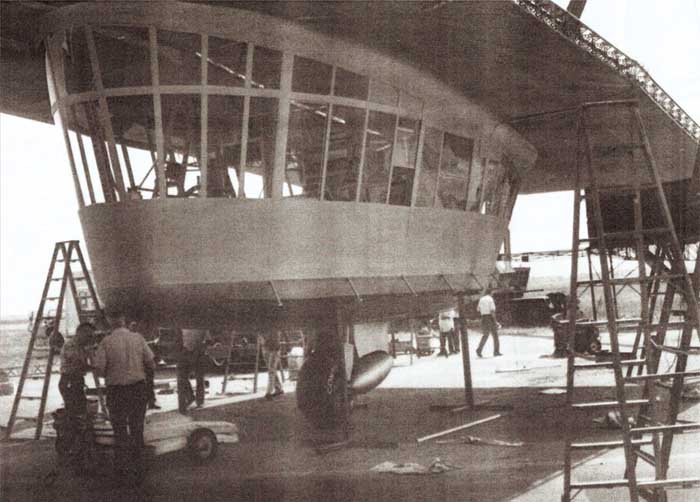

The biggest problem besides their vulnerability due to the nature of the gas bag was weight restriction. The gondola beneath the body of the aircraft was small and weight had to be kept to a minimum. The helium that kept the craft aloft was contained in air sacks so that loss of one would not be its downfall.

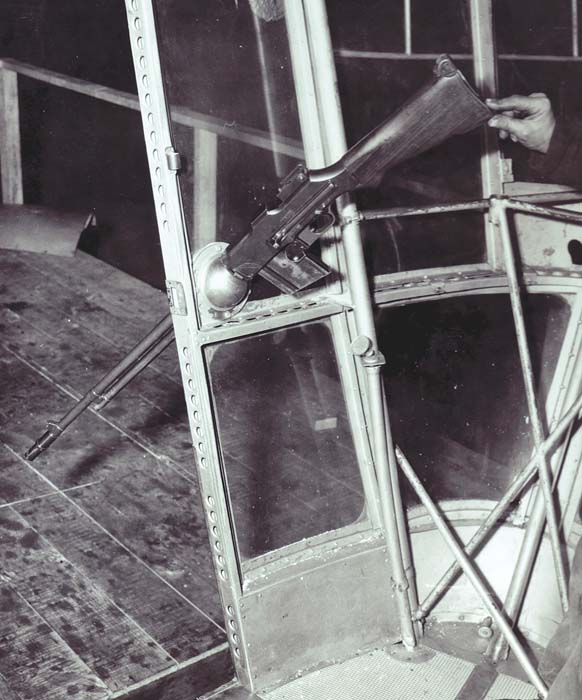

As for weaponry, the blimp carried a modest amount of incendiary bombs and also mines. Not much thought was given to defensive weaponry though their primary defensive weapon was the M3 Browning Aircraft .50. What was additionally needed was a light, rugged, and reliable machine gun. Someone had the bright idea that the BAR might admirably fit the bill. It was a battle proven, relatively light automatic gun that was accurate and easy to load with a limited but adequate capacity that had no belts dangling in the compact gondola. The BAR could fulfill one of the most effective roles for the blimp by tracking and destroying floating mines. It would also allow them to fire on small vessels and keep them under constant surveillance. The blimp helped provide an umbrella of protection along the coastal waters of North and South America, and across the Atlantic Ocean as far north as Greenland.

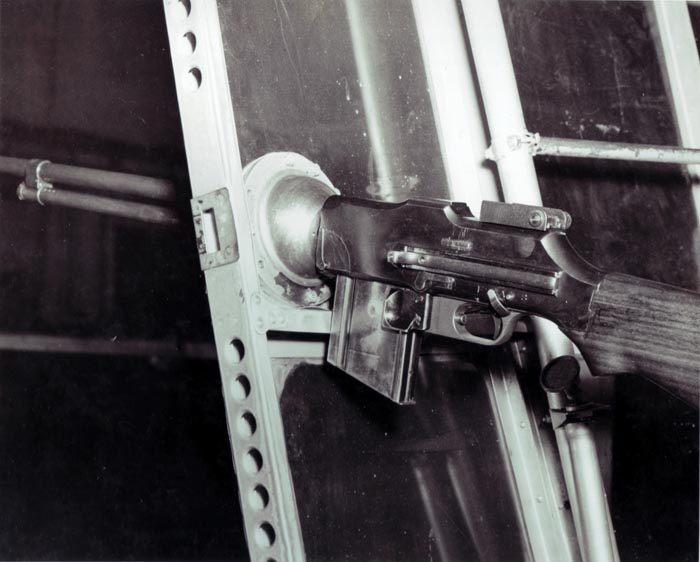

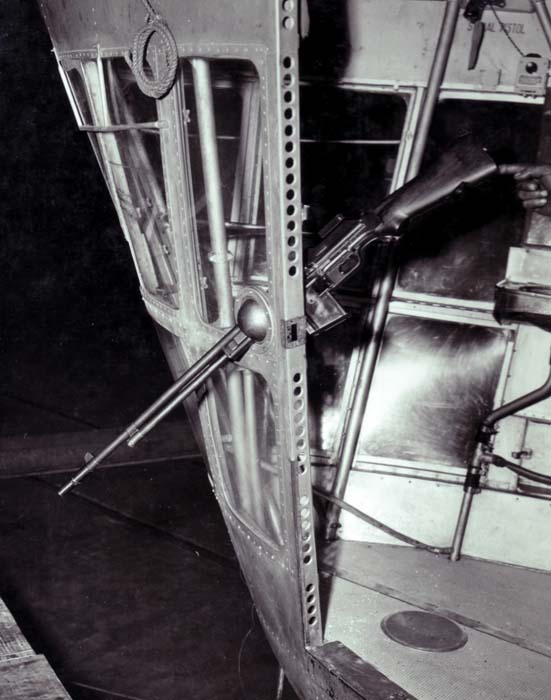

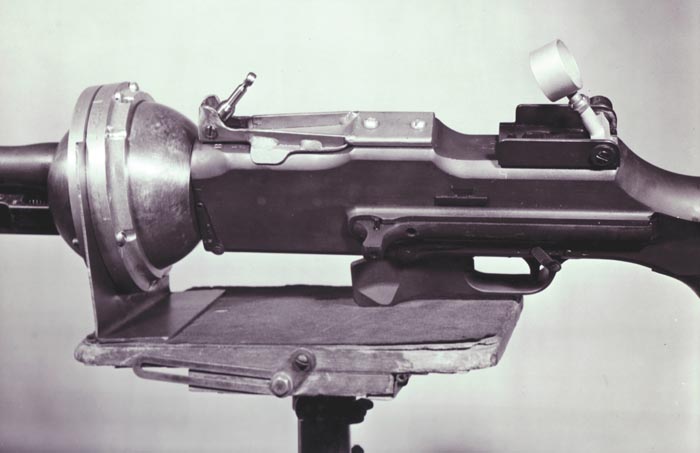

There are a few very clear and distinct photographs of an early 1918 A2 BAR mounted in a blimp. The butt stock is definitely wooden as the grain of the wood is clearly visible. The forearm has been removed so we cannot verify the vintage. There is a hinged shoulder rest so it is dated at least after October 12, 1933. One must remember that the U.S. Navy was last on the list of available technology, so it must be a very early A2 modified from a vintage 1918. The distinct wear marks on the magazine confirm that the same rifle was used in at least three of the photographs. The rear sight is of 1922 vintage and parkerized, not blued, indicating a very clear replacement to the rifle. The best time to place this BAR is between 1939 and 1942.

The foregrip has been removed for the insertion of the rifle into a robust ball-and-socket mount that is then inserted into one of the gondola windows. The operating slide is clearly visible in the photos. The flash hider is an A2 capable of taking a bipod. This rifle is mounted at the rear of the Gondola as there are much larger windows in the front and there is a latch in the door frame denoting close proximity to the exit door. One can clearly see that the selector is on F – the slow speed: perfect for accuracy and conservation of ammunition.

One picture shows the same rifle with a modified antiaircraft sight similar to one found on the Browning M3 .50 caliber. It is a collapsible ball front with a small crosshair rear. What is most interesting is how they have mounted the rear sight to the top of the BAR providing for a very sturdy mount for the sight. One wonders why it had never been done before or since.

The photographs rather speak for themselves and show a rare and unusual use of the famous Browning Automatic Rifle.

(We owe a special recognition for these rare and remarkable BAR photographs to Thomas Laemlein and to acknowledge the kind assistance of Mr. Carl Jablonski, President of the Blimp Historical Society based out of the NAS at Lakehurst, and to Ricca Zitarosa, a retired WWII veteran of the “Lighter than Aircraft Group” stationed out of NAS Lakehurst.)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V13N6 (March 2010) |