By Judith Lappin

Ten members of the Machine Gun Corps Old Comrades’ Association (MGC/OCA) travelled from all over England and Wales to attend the funeral of Albert “Smiler” Marshall who passed on at the age of 108. Not just any man, this was a very special man, born in the reign of Victoria, he saw six monarchs and innumerable Prime Ministers; a survivor people had come to believe would live forever.

Mr Marshall was the last surviving Veteran of the Machine Gun Corps (Cavalry), last surviving participant of a cavalry charge by the British Army, last man alive to have used a sword in battle, last survivor of the Battle of the Somme and believed to have been the second oldest man in the UK.

The son of an agricultural worker, born in Elmstead Market, his mother died when he was four so he spent much time with his father; on Sundays going to visit the garrison town of Colchester. Albert loved to watch the soldiers in their bright uniforms and a century later could sing the words of the marches he heard in his youth. He started work as an apprentice shipwright but his lifetime love of horses meant he soon became a stable boy.

Too young to go to war at 17, he joined the Essex Yeomanry in 1914 by lying about his age. He obtained the nickname “Smiler” after throwing a snowball at an NCO who yelled he would give Albert something to smile about.

He witnessed a cavalry charge by the Bengal Lancers and was fascinated that they didn’t bother to saddle up, just jumped onto their horses, grabbed their lances from the ground and galloped away. They routed the enemy and Smiler said it was a colossal sight.

He took part in cavalry charges using a sword: the last time this occurred in the British army. He said it was “cut and thrust at the gallop, they (the enemy) stood no chance.” Early in the war, the army High Command still believed the cavalry would be decisive in winning due to the shock and violence of their appearance.

His best pal, Lennie Passiful was shot by a sniper and later died of wounds. Many years later, Mr Marshall finally returned to France and was able to put flowers on his friend’s grave.

Always in bad situations, his faith sustained him and he would sing his favourite hymn “Nearer, My God, to Thee.”

His worst experience was watching a train load of new conscripts of the Oxs and Bucks Light Infantry arriving at the front – they were all young and looked so fresh in their clean uniforms. By next morning, they were almost all dead at Mametz Wood and “Smiler” was one of the burial party dispatched to bury the men under cover of darkness. They only had time to dig shallow graves, throwing a little mud on top. They then had to make their way back to the line by walking on the graves and the bodies so close to the surface.

He fought in France & Flanders from 1915 until he “caught a Blighty” and was sent home having suffered a gunshot wound to the hand. Though mustered out, once recovered, refusing to remain safely at home, he volunteered again and this time enlisted in the Machine Gun Corps (Cav) in 1918. He was gassed twice and said that his skin still felt dry and prickly in consequence forever afterwards.

He volunteered again after the war and went to Ireland and served there for two years, based just outside Dublin during the continuing struggles. On his return home in 1921, he married local girl Florence Day, childhood sweetheart from his schooldays. In 1926, during the General Strike, with fear of riots, many policemen were sent to the North of the country to police the strikers and thus special constables were recruited. “Smiler” became one such in the village of Great Bromley.

In recent years, “Smiler” had been lovingly cared for by Mr Graham Stark, a volunteer from the 1st World War Veterans Association. Mr Stark said that Smiler was ‘a perennial volunteer’. He had volunteered to go to war twice, then to Ireland, then to work as a Special Constable and he also volunteered for the Home Guard in World War II even though he lost his right eye in 1939 when a clipping from a horse’s mane damaged his eye and it had to be removed.

After his marriage, he worked for the Essex & Suffolk Hunt. Later, when his then employer, a Captain Mumford, moved from Essex to Surrey, “Smiler” and family moved too. He always worked with horses and eventually worked for the Maples family on their farm as a general handyman. Here he was given a “tied” cottage at Ashstead, where he could live while he worked for them. This proved to be his home for the remainder of his long life. He could still be found at age 100 helping out in the greenhouses of the estate.

His war experiences remained private until he was very old. He then joined the Royal British Legion and the WW1 Veterans Association and, along with other Veterans, went to Passchendaele to attend the 80th anniversary of the battle. Only then did he start talking about the crucible that was the First World War.

He attended the services of Remembrance at the Albert Hall and the Cenotaph. He sang trench songs at Rochester Cathedral, receiving a standing ovation. Along with all surviving veterans, he was awarded the Legion d’Honneur, as a thank you for his service to France, the highest award it can offer.

With the passing of time and the realisation that there were few left to give a first person account of “the war to end all wars,” documentary makers sought out the surviving Veterans and “Smiler” became a star, with his vivid memories, strong singing voice and smiling face. No one who has seen him giving interviews could fail to be moved, especially when he sang those long forgotten cheery and often cynical songs. He bore witness on behalf of himself and fallen comrades.

“Smiler” was the wonderful guest of honour at Exercise Parting Shot in 2002 when Lt. Col. Edward Waite Roberts and Maj. John Butler organised a superb event in aid of the MGC/OCA at Bisley. (SAR was there. Read our coverage of this event in Vol. 6 No. 11.) This was an opportunity to fire a Vickers using live rounds, a unique experience in the UK, to mark the 85th formation of the Corps. Mr Marshall was thrilled to fire the gun again. Despite the gap of so many years since he last fired one, his fingers went automatically to the Vickers trigger. Readers may be interested to know that Mr. Harry Patch, the other Veteran in attendance that day, formerly of the 7th Battalion Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry, is still alive and aged 107 (born 17 June 1898). Mr. Patch did not serve with the Machine Gun Corps, but was nevertheless a machine gunner. He is a survivor of Passchendaele when a shell burst by his 5-man Lewis gun team killed three of them.

Gentlemen from the Vickers Machine Gun Society attended the funeral, offering their services as pall bearers and a group dressed in Middlesex uniform formed an honour guard. Despite the light rain, mourners started to gather at the house from 11 a.m. At 11:30 a.m. the horse drawn carriage, which was to take “Smiler” on his final journey, arrived at his home.

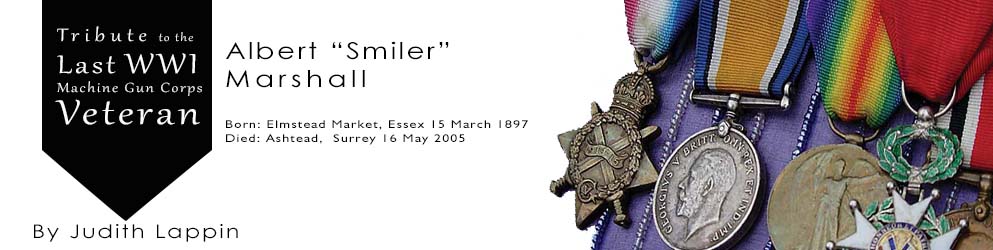

Near the horse drawn carriage and lying on a Union flag was his leather ammunition belt, soft cap, tin hat and medals and, we were honoured to note, the Machine Gun Corps Old Comrades’ Association wreath.

His medals are the 15 Star, British and Victory Medals, the Legion d’Honneur and The Special Constabulary Long Service and Good Conduct Medal.

His family lovingly brought out their floral tributes, which were placed around the coffin and atop the carriage. His son’s wreath was placed on his coffin, the MGC wreath sharing this place of honour. By this stage, about 100 mourners had gathered, family, friends, neighbours, co-workers and representatives of various military organisations and two terriers representing his love of hunting.

The pall bearers carried Mr Marshall’s coffin out to the carriage where a matched pair of dark horses with Victorian plumes on their heads stood ready to pull this special old gentleman on his final journey. Along the beautiful Surrey lanes he went with those who loved and respected him following behind.

When the procession reached Ashford High Street, Surrey police stopped traffic and, even in these cynical days, virtually every shop keeper came to the door of their business and all pedestrians stopped to silently watch. In these days when we conduct our lives at the double, it was surprising and gratifying to see a busy town pause. Albert Marshall had served and ensured that his countrymen live in peace. It was fitting those same countrymen should stop for a moment to honour him. The procession turned up the long approach to St Giles’ Church, the same church where Mr Marshall had worshipped every Sunday for more than half a century.

Tony Cozens and Andy Bray carried the two Machine Gun Corps standards accompanied by a single Royal British Legion standard bearer and lead the way into the church where another 200 or so mourners were already gathered. The Vicar, Reverand Dr. Bob Kiteley, conducted a fitting service of thanksgiving, honouring a very special man and his long and fruitful life. He said, “It was almost as if he might go on for ever but we are all mortal and have to go Home in the end. Well done Smiler.”

In church, his son smiled when he said his father had lived a carefree life because he had never had to worry about paying the mortgage nor rent on a home. Though he outlived his employers, their daughter lived next door and their grand-daughter, Mrs. Davinia Vanstone, gave a eulogy at his funeral. She happily recounted how Smiler taught her to ride and how, on her wedding day in 1988 when he was aged 91 years old, she went to the church in a horse drawn carriage with Smiler, wearing hunting pink, acting as her outrider.

Finally came the hymn which had sustained him so often during life, followed by The Last Post. We would all benefit by living by the same simple rule “Smiler” lived by: If you cannot do someone a good turn, at least don’t do them any harm.

The clouds had cleared and there was weak sunshine as we walked the few yards to his final resting place. He had outlived her by over 30 years, but “Smiler” was finally going to Florence, who had died in 1984 and they would be together again at last.

With his loving family looking on, the MGC standards fluttered as the honour guard fired a volley over the grave as his coffin was lowered into the ground. (The bullet cases were given to his grandchildren.) A huntsman’s horn was blown, a sound Mr. Marshall had loved throughout his life. People stood around talking, in no hurry to leave the man as he had been in no hurry to leave this life.

Slowly the crowd dispersed, going home or, since this was a quintessentially English day, to join his family who had invited friends to gather in the church hall where everyone drank cups of tea, ate delightful sandwiches and cakes while exchanging “Smiler” stories.

Albert Marshall’s legacy includes two surviving children John and Geoffrey, 12 grandchildren, 22 great grandchildren and 4 great great grandchildren

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V9N1 (October 2005) |