By Michael Heidler

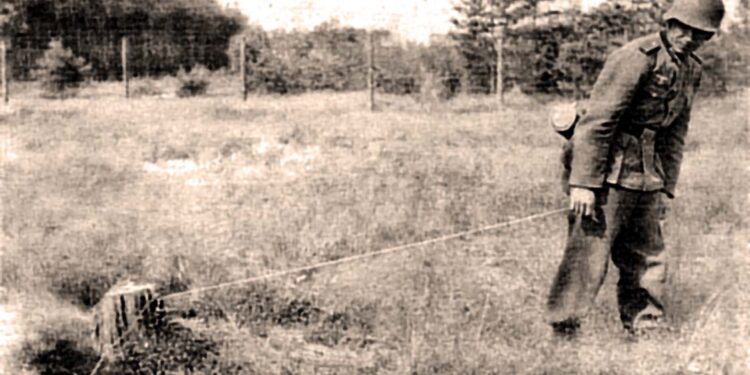

With thinly staffed Front lines, the gaps between the individual sentries must somehow be closed. Especially in dark, rainy or windy nights, the moving shadows and the sounds of enemy soldiers are hardly to be noticed at a distance. Simple alarm devices with trip wires have proven themselves in such cases. At some distance from the Front line or at particularly difficult-to-monitor terrain, the wires are placed near the ground, well camouflaged, and when touched by enemy soldiers they activate an alarm signal.

Depending on the situation, a silent alarm can be useful. For example, an empty shell casing is fitted with a metal hammer and hung up as a bell at the next post. A pull on the tension wire in front of the position reveals enemy activity in time and gives the sentry an opportunity to inform his comrades; for example, via an extra alarm wire to a rearward camp place. The system had probably proved itself in WWII, as written in a German instruction: “In this way it is not only possible to get along with small guard positions and to relieve the often overstretched troops, but also to organize the surprise of the sneaked in enemies and to bring in prisoners.”

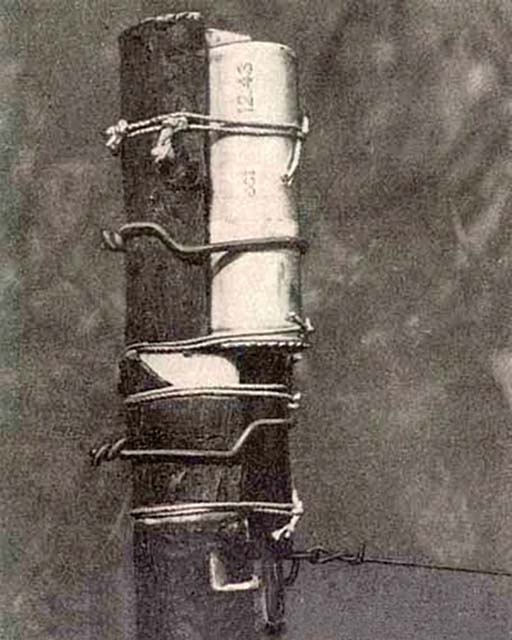

But often enough, the situation on-site and the number of soldiers did not allow the enemy to get that close or the own position was already sufficiently defensive. Back then, it was important to withdraw the protective darkness from the enemy in the nick of time. In the 1930s the development of a so-called “Alarmschußpatrone” (alarm shot cartridge) began. From 1936, it was manufactured by the companies Nicolaus and Eisfeld. Mounted in special holders on trees or posts, they were activated by the enemy via a trip wire. Then a 2m high flame shot up and illuminated the surroundings for about 10 seconds up to approximately 15m. The early cartridges still had moisture-sensitive cardboard cases, but from 1939 an improved model with an aluminium case and an aluminium lid for protection against the weather was manufactured. The firing of such cartridges from a flare pistol was strictly forbidden.

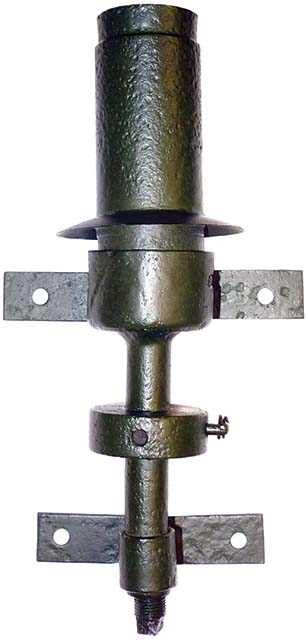

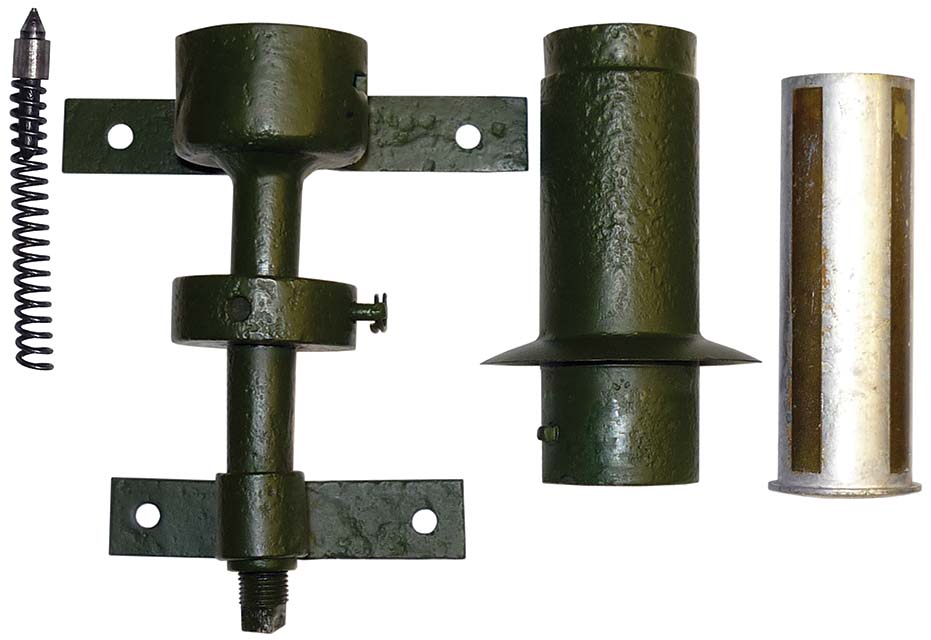

In the further course of the War, in 1941– 1942, in view of the increasing use of such signal ammunition, the Heereswaffenamt (Army Weapons Office) demanded the development of a signal cartridge with a firing device as a ready-to-use unit. The result was introduced in 1943 and replaced all previous models. This device, called “Alarmleuchtzeichen” (alarm flare signal), consisted of a tin can with a diameter of 40mm, filled with a pyrotechnic charge and pre-fitted with a primer. The firing pin assembly was screwed onto it. The whole unit was attached to a mount by means of a clamp. The mount had three holes and could be nailed or tied to a tree or post. The unit weighed 250g and was delivered ready-packed in a cardboard box together with 80m of trip wire. During assembly, it was important to ensure that the device was placed in the expected direction of the enemy and that an illumination or blinding of their own positions was avoided at all costs. The illumination lasted about 18 seconds and was sufficient for a radius of about 50m at night.

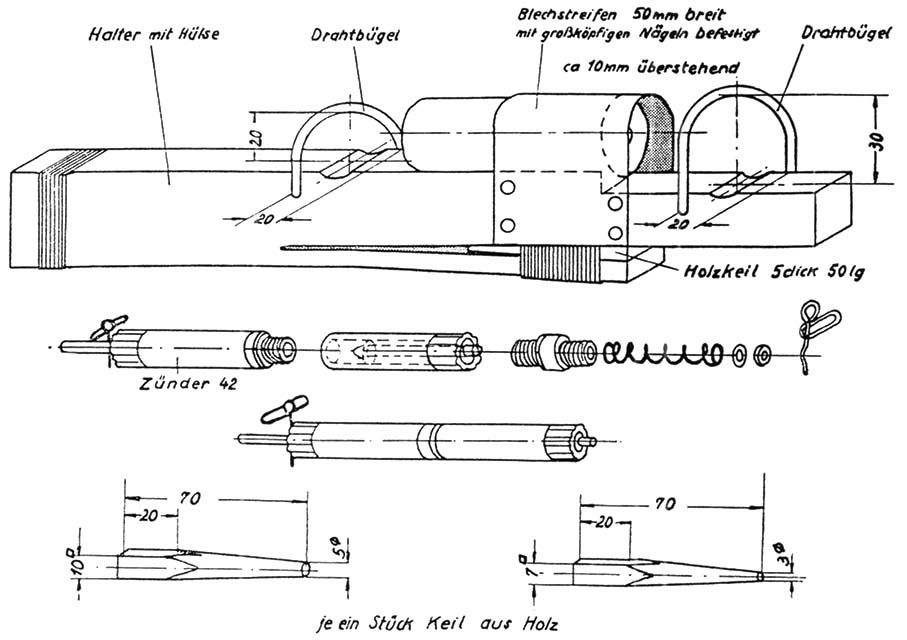

This series-produced alarm device had worked well, but the Front lacked supplies. Soldiers are quite inventive in times of need, and so they made various improvisations from all kinds of materials. The pull fuze Z.Z.42 (Zugzünder), which was available almost everywhere and had a very simple design, served as the igniter for the normal flare pistol cartridges. It basically consisted of a Bakelite tube with a spring-loaded firing pin with a safety pin. This handicraft work was not hidden from the Army Weapons Office, and the pencil pushers working there were not very enthusiastic about it. In the military, do-it-yourself magazine, Von der Front für die Front (From the Front for the Front) of June 1944, it was therefore especially pointed out that these makeshift devices were for the most part not safe to handle. For this reason, a detailed construction manual for the making of an alarm device was printed in the same issue, which “can be easily made from troop resources, is accident-proof and also works.”

But even this device, recommended by the Army Weapons Office, was unnecessarily complicated to produce. The instruction 29/5 “Mine Barriers in Winter” from August 1944 shows how it can be made even easier. A lengthwise divided piece of wood could be hollowed-out so that a Z.Z.42 and, above it, a flare cartridge can be installed. And in a suggestion of the Volkssturm issue of the do-it-yourself magazine, a hollowed-out stake with a Z.Z.42 igniter inserted at the side and a detonator were used. More was not even necessary.

Interestingly enough, the design of various launchers for flare cartridges that were produced during the War, suggests a type of series production. The devices don’t carry manufacturers’ information or acceptance marks, or in some cases, the markings are no longer visible due to their state of preservation. Thus, it remains in the dark by whom, where and in what quantity these devices were manufactured. A model was found in France and described in the Intelligence Bulletin of the U.S. Army in the May 1944 issue, and there were also relics dug up at the Eastern Front. Today, the last surviving examples are rarities, because unlike flare pistols, such alarm devices were useless after the War and mostly went to scrap.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V24N8 (Oct 2020) |