Among the great revolvers of all time is the Webley. Webley handguns fought in every conflict the British Empire was embroiled in from 1880 to 1963 and beyond. The odds are heavily in favor of the supposition that somewhere the Webley is still serving ably. While designed as rough and ready service revolvers, there is now some collector interest in the Webley. A chaotic loss of factory records has resulted in a daunting proposition to researchers, but then few Webley revolvers are true rarities. The condition of each should be your guide both as a shooter and as a collectible. The Webley is indispensable to anyone who desires to own a complete collection of World War One and World War Two revolvers. The Webley also served as a front line handgun during various Communist insurrections including Korea. The Webley was also a police revolver not only in England but also in practically every country under British influence. Officially, the Webley revolver in one form or another served the Empire as standard issue from 1887 until 1963, when the Browning High Power took its place. Just the same, the revolver was still on hand well into the 1970s at many British outposts.

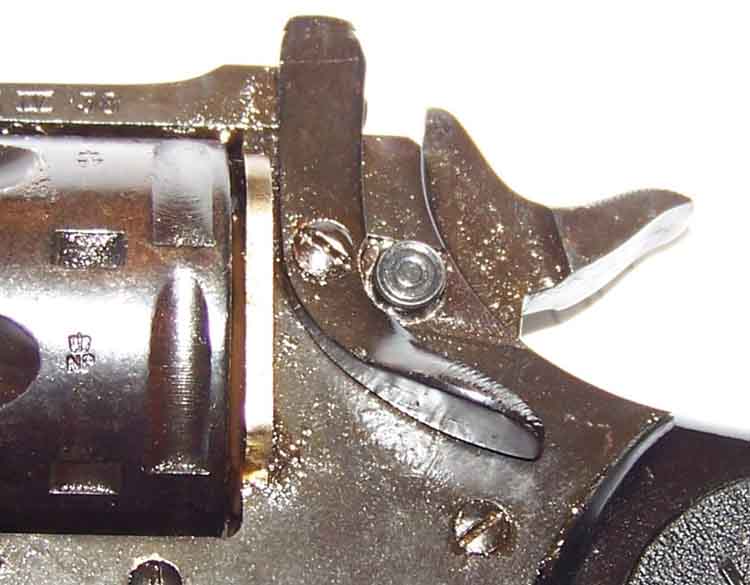

The important features of the revolver are automatic extraction and double action trigger action. The top break extraction is a very desirable feature in a combat handgun. After expending the gun load, the barrel latch was activated and the barrel grasped to turn the barrel down. The extractor spring sprung the ejector to its full extension, ejecting all shells at once. The only disadvantage was that the shells were all ejected, fired or not. It was devilishly difficult to simply top the revolver off after a round or two had been fired. The American Smith & Wesson break top system was much the same. A competitor in America, the Merwin and Hulbert, used a special system in which the barrel was drawn forward and only fired cases ejected. I mention these competing systems because all had one shortcoming: they were not practical for cartridges longer than the .38 Smith & Wesson, .44 Smith and Wesson or .455 Webley. The leverage and length of the extractor were suitable only for short case revolver rounds.

The Webley Mk I was introduced in 1887 and saw action in Africa against aboriginal tribes. By 1900, the improved MK IV was in use by the British. The MK VI differs considerably from earlier revolvers as there is a step in the grip that gives more positive hand fit during double action fire. The Webley self extracting revolver, as the company called it, had few real competitors, and those armed with substitute standard handguns often complained. It is important to remember that Webley also produced solid frame revolvers for police and civilian use. Among the large numbers of Belgian and Spanish Ironmongery are a great many Webley copies. Some are well fitted, others are best suitable for use as fishing weights, and none are as well made or robust and the genuine Webley. Properly called Webley and Scott revolvers, these revolvers proved reliable in hostile environments including World War One trenches. Interesting to note, the obvious advantages of speed loads for the fast loading Webley revolver was developed as early as 1889 with some speed loaders issued by 1902. My research is imperfect but it seems that speed loaders were never issued in great numbers. The Prideaux speedloader is a complicated all metal device that when found commands as high a price as the handguns themselves.

Immediately after World War One, there was a hue and cry to replace the Webley .455. The Mk VI was larger and heavier than the original revolver but quite comfortable to fire and use. Just the same, the Army called for a smaller caliber revolver. Ease of training was one reason for the adoption of a .38 caliber revolver. Many other nations have regretted going to a smaller caliber handgun, but the British seem to have hit the magic number with the .38 and the loading they used. Restrictions upon the length of cartridge that could be used left little choice. The .38 Short Colt or .38 Smith & Wesson were the only likely choices. The .38 Smith & Wesson was chosen as a base line, with an unusual bullet. The British felt that by using a 200 grain bullet some measure of stopping power would be retained. The original loading was a 200 grain round nose lead bullet at 650 fps. The new cartridge, actually a special loaded .38 Smith & Wesson, as distinct from the longer .38 Special, was termed the .380 or .38/200. The Mk IV Webley revolver is a basically a downsized .455 but also based upon the .38 caliber police revolvers. It is interesting that after expressing much interest in the Webley product, the government deigned it appropriate to develop their own handgun at Enfield Lock Small Arms Factory. The Revolver, No. 2, Mk I is similar in outline and operation to the Webley. It is a break top revolver with simultaneous ejection. Many of the detail changes are primarily for ease of production. As the story goes, after an accident in which a tank driver suffered a self inflicted wound, the Enfield was changed to the Mk I*, denoting a spurless hammer. Essentially, these were double action only handguns. Webley and Scott felt that the situation was more than unfair and brought suit against the government for their actions. The government did pay Webley, but also ordered great quantities of the Webley during World War Two as the Enfield Lock location was not adequate alone to meet the needs of the British Army. Some half a million Webley .38/200 revolvers were produced. This number is approximately four times the production figures for the .455 revolvers.

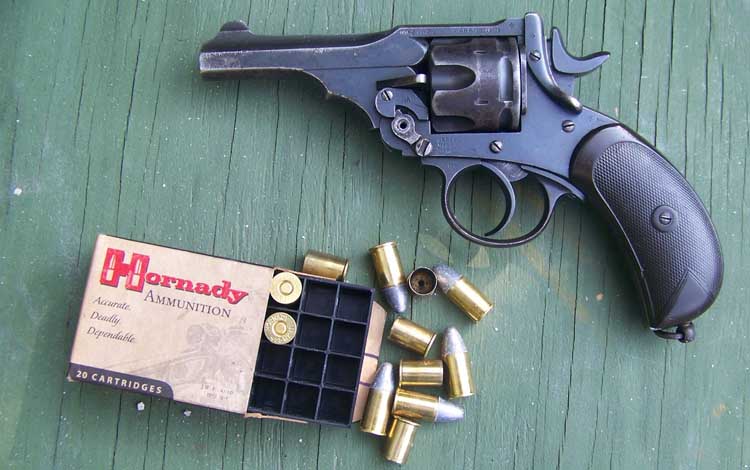

The revolvers illustrated in this report are typical Webley revolvers. The MK III .455 was produced prior to the Boer war. It is in the original caliber. Quite a few have been altered to accept the .45 Automatic Colt Pistol cartridge with the use of moon clips. This was done as an expedient when Webley ammunition was difficult to impossible to obtain. While the .455 frame has been able to contain this pressure, common sense tells us there is a disparity in pressure. The .455 Webley with its 265 grain RNL bullet generates 650 fps at 12,000 pounds per square inch pressure. The .45 ACP cartridge with a 230 grain RNJ bullet generates 820 fps at 18,000 pounds per square inch. Today, good quality ammunition is available from Hornady. This relieves us of the necessity of facing off the cylinder and recoil plate in order to fire our Webley revolvers – but converted handguns WILL NOT accept the .455 ammunition.

The MK III is very comfortable to fire. While it looks ungainly compared to modern revolvers, the Webley is far from it. The grip feels good in the hand, the double action trigger is smooth, and the sights are good for close range combat shooting. Our extractor spring is weak, which limited the experience, but overall this is a handgun that must have given officers much confidence. Recoil with the .455 Webley is insignificant. The lighter .38 revolver is impressive in fit, finish, and fast handling. This revolver was delivered from Southern Ohio Guns packed in Cosmoline. After the heavy grease was removed and the revolver examined, it was pronounced as new and appeared unfired. Balance is excellent. The Webley .38 is lively in the hand and it gets on the target quickly. The trigger is smooth and the combat style sights are excellent. We were able to obtain a small quantity of Winchester produced .38 Smith & Wesson loads. The 146 grain RNL bullet averaged 580 fps from the revolver’s four inch barrel. Accuracy is problematic in the target sense but good in the true sense of marksmanship, in hitting the target on demand. We fired a four inch group at 15 yards with all six chambers. While the caliber is questionable for combat use, the handling of this revolver is first class. I attempted to duplicate the original loading with a combination of RCBS dies, Starline premium quality new cartridge brass, Winchester primers, WW 231 ball powder, and the Magnus cast bullet at 198 grains. I was able to work up a loading that exhibited 667 fps. The thump in the hand remained pleasant but noticeably stronger than with the 146 grain loading. The British believed that a heavier bullet at lower velocity working over a target over a longer time would be more effective than a lighter higher velocity bullet. There may be something to it. The Webley revolvers are a piece of history that is both interesting and tangible. At present, Webley revolvers are affordable and readily available. They are also shootable, given an example in good condition.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V14N8 (May 2011) |