Few men alive today have ever had the opportunity to fire a Nordenfelt manually operated machine gun. During a recent Small Arms Review Expeditionary Force to the Pattern Room at the Royal Armouries in Leeds, England, a delightful, unassuming quiet gentleman by the name of Neville West was assigned to assist us in our research. During our days of photographing early historic machine guns, he mentioned in passing that, as a young man in the army, he had the opportunity to restore to firing condition and actually fire a Nordenfelt machine gun. This is his story, being the reminiscences of 24006056 Sergeant Neville West, Intelligence Corps, seconded to the Sultan’s Armed Forces in 1972.

History

The Sultanate of Oman has a long and interesting history. Until the early 1970s the country went by the name of Muscat and Oman echoing the historical difference between the coastal people of the area surrounding Muscat and Mutrah on the one hand and the people of the mountainous interior, Oman, on the other. Knowledge of this difference, this division, and its consequences is important for an understanding of the history of the country and the part played in it by Nordenfelt machine gun No. 6024

From the end of the 10th century to the early 17th century, Oman’s contact with other countries was limited. The first Europeans to appear off Muscat in the first decade of the 16th century were the Portuguese who in 1507 attacked and looted the town. Soon after them came the English, the Dutch and the French, all with their sights on India or further shores. There was an unsuccessful invasion by the Persians in the early years of the 18th century and another unsuccessful one very early in the 19th century by the Wahabis from what is now Saudi Arabia.

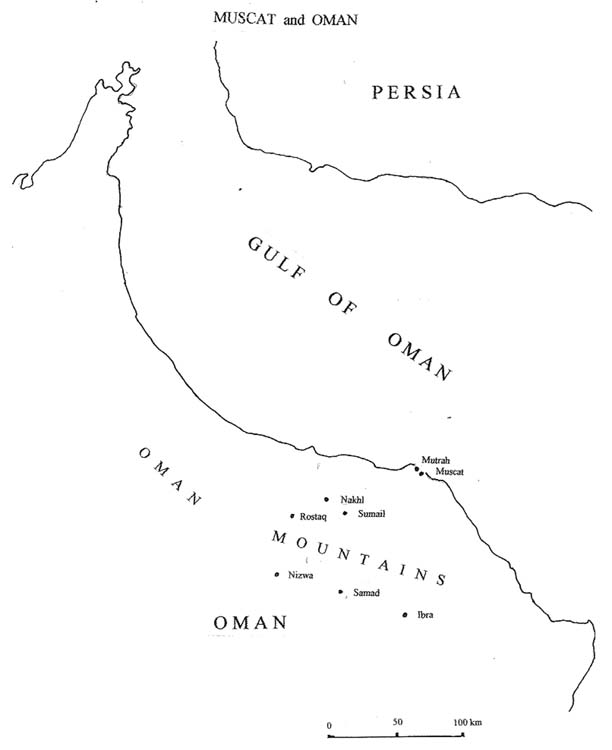

In the first quarter of the 17th century there were at least five petty rulers in Oman reigning at Rostaq, Nakhl, Sumail, Samad and Ibra, together with tribal leaders elsewhere. The history of that period is a story of internecine tribal squabblings leading to civil war and its erosive consequences particularly with regard to water resources and agriculture. In the late 18th century the concept of ‘Muscat and Oman’ came into being when one of the more effective rulers in the interior moved his capital from Rostaq to the coastal town of Muscat, which was flourishing as a trading center. The move, the name and the fact that over the years the port of Muscat changed hands many times – at one time the Turks, at another the Persians, then the Portuguese and finally the Omanis themselves – all accentuated the position of the coastal community at the expense of the interior mountain community and created discord that lasted well into the 20th century.

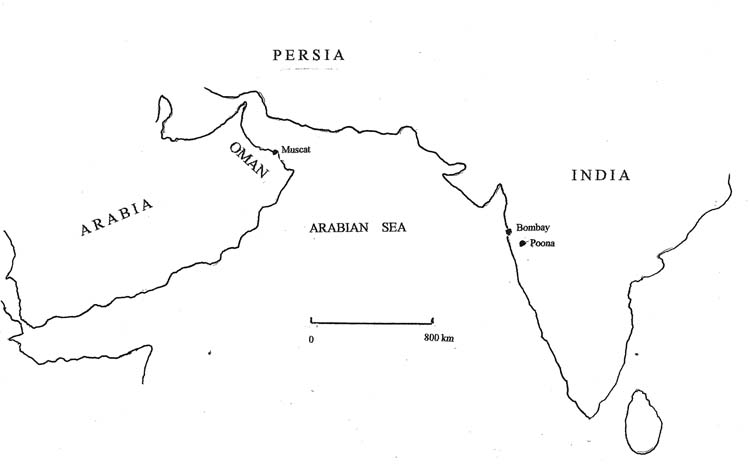

In the early 18th century certain ill-disciplined captains of the Omani navy attacked trading ships of the Honourable East India Company sailing between India and England and that in turn involved contact with the English government. The piracy was to have far reaching effects on Oman’s history and resulted in a series of treaties between Oman and the Honourable East India Company. One important treaty was that of 1798, the aim of which was not so much the suppression of piracy – always a problem – as an attempt to keep the French from India. Britain was at war with France and it was feared that the latter might use Muscat as a naval base from which they could launch attacks on British and Indian shipping; or even as a staging post for an invasion of India. As a result of these fears a treaty of friendship with Britain was concluded with the reigning sultan – a treaty which has endured to this day.

Throughout the 19th century there were various other treaties with the British. Two significant ones which hit Oman entrepreneurs hard were those connected with the abolition of the slave trade and the sale of arms. At the same time larger, faster European shipping and the opening of the Suez Canal reduced the income of Oman drastically and as the country sank further and further into recession so unrest and unease increased. The Sultan’s finances were in an unhealthy state and his requests for assistance were not immediately heeded by the Government of India – until the French once again started to show an interest in the area.

By 1871 unrest in the interior was considerable. There was a renewed struggle for power upon which was superimposed a deterioration in the relations between the tribes of the interior where, based in Nizwa, the Iman, the spiritual leader of Oman, was exercising power and the writ of the government in Muscat did not extend.

In 1895 tribal resentment flared into active rebellion. A surprise attack on Muscat by tribesmen succeeded and the town was captured and looted. That the Sultan survived was due almost entirely to the support of the British Government; the rebels were paid off and Muscat retaken. Sir Arnold Wilson noted that in 1896, “…the Government of India presented Faisal, the Sultan of Muscat, with two mortars and ammunition as an addition to his means of defence.” In the early years of the 20th century the Omani tribes once again rose in rebellion under the so-called “Iman” and Mutrah, Muscat and other ports were threatened. J.E. Peterson writes that in order to prevent a victory by the Imanate forces and to maintain Britain’s influence in the area, Indian Army troops, with British and Indian officers, were stationed in, or near to Muscat in July 1913. In a private communication to the author, a former officer in the Sultan’s army wrote, “Unfortunately historical details of the British and Indian Army presence in Oman around the late 19th/early 20th century are sparse. British involvement in Oman’s military history is minimized in most modern accounts and even the painting of the Battle of Bait al Falaj in 1915 has been doctored, turning the British officers into Omanis and changing the hats of the sepoys into Muscat Regimental balmorals, even though the Muscat Regiment did not exist then.”

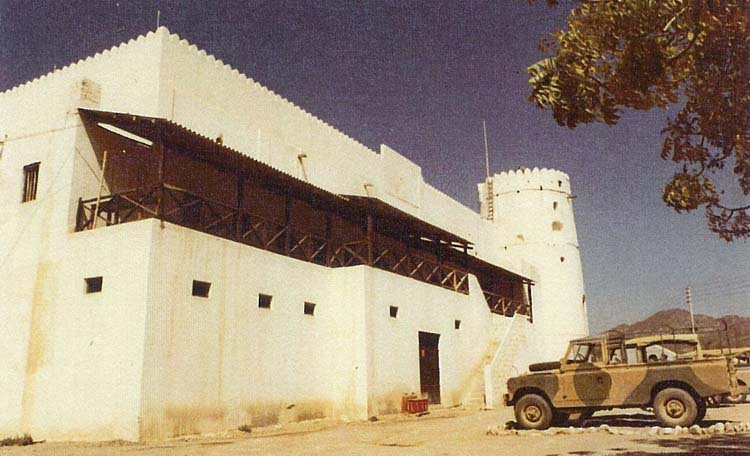

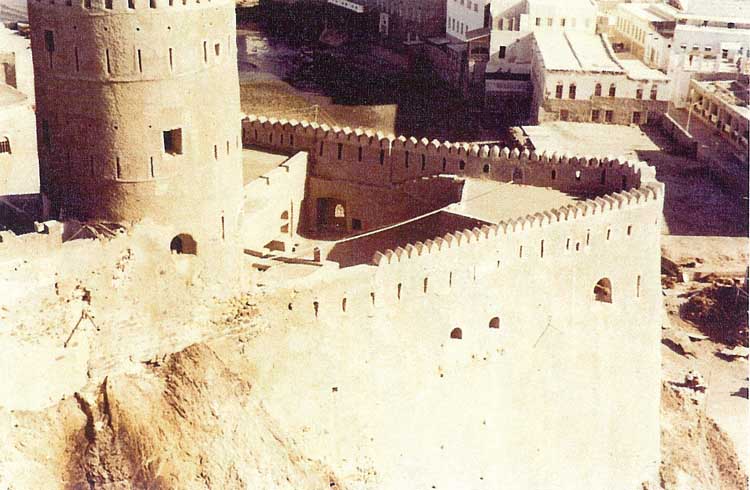

The costal area of Oman, writes W.D. Peyton, was raided for the last time in 1915 when a rebel force said to have numbered some 3,000 was defeated by 700 Indian troops at Ruwi, two or three miles south of the small fort called Bait al Falaj. In 1972, when the Nordenfelt machine gun No. 6024 was restored, Bait al Falaj was the Headquarters of the Sultan’s Armed Forces. It was in front of the main gate of the Headquarters that the gun was found. F.A. Clements describes these Indian troops as a battalion of Baluch infantry with British officers sent by the East Indian Government to support the Sultan. J.T. Gorman gives more information and refers specifically to the 2nd Battalion of the 4th Bombay Grenadiers. At the time however, this unit was designated the 2nd Battalion, the 102nd King Edward’s Own Grenadiers. Whether this unit consisted of Baluchi troops or whether it was Russell’s Infantry has not yet been ascertained. The 2nd/102nd were redesignated the 2nd/4th Bombay Grenadiers in the Indian Army reforms of 1922.

Gorman writes, “…the Viceroy when he inspected the regiment and Russell’s Infantry at Sarseit (a coastal village some 3 miles north of Bait al Falaj) on his visit to the Persian Gulf spoke of the success of the operations against the rebels in Oman and thanked Colonel Edwards and the regiment in the name of the Government and the people of India. The Grenadiers returned to Poona in India in April 1915. Medals and decorations were presented and speeches were made that referred to their recent fights both in the field and against the assaults of sickness at Muscat which had added fresh glory to their past record.”

It is recorded that Indian troops left Oman in 1921 when the country had settled down. The troops can not have been the Grenadiers for in November 1915, the 2nd/4th, up to full strength of 519 officers and men, embarked for Mesopotamia. It is very probable that the ‘assaults of sickness at Muscat’ must have attacked both Indian battalions mentioned earlier leaving both of them under strength so that the 700 Indian troops mentioned by Peyton probably refers to them both. It is likely that it was Russell’s Infantry that stayed on until 1921.

The subject of weaponry used by soldiers of the Indian Army at this time is complex. Because of the mistrust of Indian troops engendered by the Mutiny in 1858, most Indian Army units had been issued with obsolete, single shot smooth bore weapons; but by 1890 all units of the Indian Army had been re-equipped with rifled weapons and, generally speaking, the equipment of the Indian Army units was on a par with their British counterparts. Certainly by 1900, Nordenfelts were considered to be obsolete in the British army and numerous photographs taken at this time show Indian Army units equipped with Maxim machine guns.

It is very probable that it was in the last decades of the 19th century or the early years of the 20th century that the Nordenfelt gun and ammunition, although not fully compatible, arrived in Oman as aid from the Indian Government. To the rear of this gun’s magazine, on the body cover, and to the left of the gun’s number are engraved the letters “E I G,” the standard abbreviation for East India Government.

It would be interesting to know whether any units of the Indian Army were still using Nordenfelts in 1915 and, if they were, did either Russell’s Infantry or the Grenadiers leave one behind on their return to India? In a letter from Dr. Peter Boyden of the National Army Museum, London, he writes that, “The Indian Army units often continued to use older types of weaponry after they had been replaced by the British Army and it is likely that the Indian troops arriving in Oman in 1913 were armed with 24 year-old machine guns. The handbooks for Nordenfelts were still being reprinted in 1899.” This gets nearer to answering the questions, “Who brought it to Oman and when?” The answer to the question as to why it was sent to Oman is almost certainly that it was an aid to securing the stability and security of that country in the early 20th century.

The Nordenfelt

Each day for months we had passed this gun on the way to our work-place in the old fort of Bait al Falaj. In 1971, this fort was the headquarters of the Sultan’s Armed Forces and it was to this unit and location that Dick Valentine of the Royal Engineers, and myself from the Intelligence Corps, had been seconded. The old fort has since been extensively renovated; its surround landscaped and is now the Sultan’s Armed Forces Museum.

This early machine gun fascinated us and, after a close inspection together with the aid of the text and diagram from Dudley Pope’s Guns, we realized that the Nordenfelt was still in working order. At this time we had no plans to do anything with it.

The gun is one of a series of manually operated weapons produced in the latter part of the 19th century. The earliest Nordenfelt machine gun was designed in 1872 by Heldge Palmcrantz, a Swedish engineer but the series was both manufactured and marketed by Thorsten Nordenfelt, a Swedish financier, 1842-1920. The guns came in various calibers from rifle caliber to one inch and with one to twelve barrels, which were fixed horizontally in a rectangular frame.

On the multi-barrel models, a tall rectangular magazine or hopper, holding up to two hundred and fifty rounds, is positioned on the top of the gun over the carrier block; the cartridges being gravity fed into a slot behind the chamber. The whole mechanism is operated by a lever on the right hand side. Pushing the lever forward chambers the rounds and at the end of the lever’s travel the firing pins are released and the cartridges fired. Pulling back this lever cocks the firing mechanism and at the same time ejects the empty case. Chapter 14 of Col. George Chinn’s book The Machine Gun contains detailed information of the mechanism.

In his book, William Read shows a Battery Sergeant Major of the Royal Artillery in 1884 firing a three barreled .45 caliber Nordenfelt. The gun that is the subject of this article has five barrels in parallel, each being .45 caliber and chambered for the Martini-Henry rifle solid brass case. A brass plate on the body cover bears the date 1880 but whether this refers to the date of manufacture or the date it was taken into service is not known; it may relate to the Government specifications of that date for Nordenfelts in British service.

The gun could be fired mounted on its two wheeled carriage. As an alternative, it could be dismounted from the wheeled carriage and fired from a tripod formed by its trail and the two front supports. Nordenfelts of this type, weighing 150 pound upwards, needed special mounting or a mule train and a large gun team.

The Indian soldiers of the gun team which brought it to Oman would have had four mules to help them. The first mule would have carried the gun itself, together with some ammunition hoppers and ammunition. The second mule carried the trail, together with more hoppers and ammunition. The third mule carried the wheels and axle, a pick, a shovel and forage whilst the fourth mule carried yet more ammunition and hoppers. In all the team carried 1,600 rounds and there were other ammunition mules, each carrying 1,200 round, in attendance.

The Discovery of Ammunition

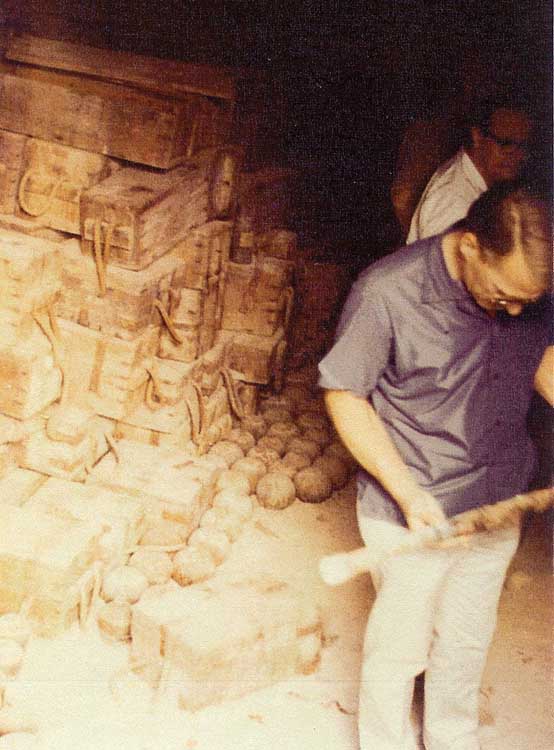

The event which started the ball rolling was the discovery of a wooden box full of .45 caliber Martini-Henry ammunition in an abandoned and rat infested storeroom in Fort Mirani, an old Portuguese-built fort, overlooking Muscat harbor.

The Mark III ammunition was neatly wrapped and tied in packets of ten rounds and was clearly labeled as being of the rolled brass case type produced at the Kirkee Arsenal in India in 1896. Interestingly this is the same year in which Sir Arthur Wilson notes that the Indian government gave military aid to the Sultanate.

We had some spare time in the early afternoon on most days when it was too hot for any but essential work and we reasoned that since we had an unusual gun with suitable ammunition we ought to do something positive with them both.

Our ammunition trials with the Martini-Henry rifle satisfied us that all was well in that there were no adverse effects to the firearm or ourselves. We were aware that the brass plate on the body of the Nordenfelt specified that it was chambered for the solid brass case whereas our cartridges were of rolled brass. We did wonder what the implications might be and we were soon to find out.

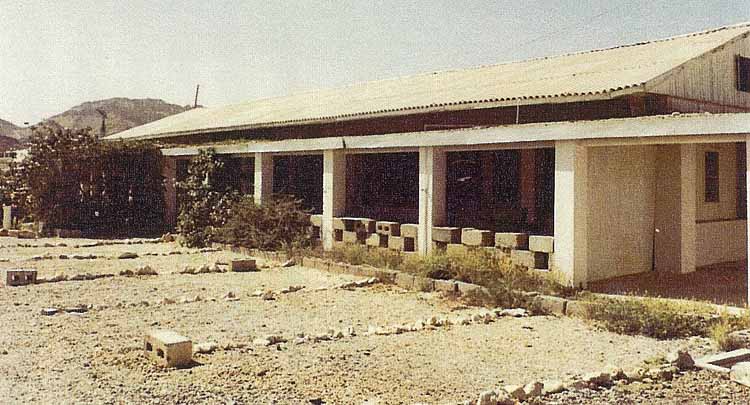

It was not our intention to conserve this gun – it was to be our plaything. After permission had been granted for us to proceed with this restoration project the gun was moved to our workshop – the veranda of the British Sergeants’ Mess.

Restoration Commences

Our first task was to clean off the layers of sand and black paint, to strip the gun down, to clean the barrels and working parts, to oil them up, to reassemble the bits and pieces, repaint the carriage and fire the gun until the ammunition ran out. As far as we could ascertain the gun had originally been painted grey and we were fortunate in being able to cadge some suitable paint from a passing Royal Navy warship. That achieved, we settled down to work; a labor of love during a very hot Omani summer.

Cleaning away rears of accumulated dirt was a sweaty, tedious but not particularly difficult job. We suffered from sweat rash and blisters on our hands and forearms but that did not bother us unduly. As far as I can remember, stripping the working parts, cleaning, oiling up and reassembling them presented no great problems – getting the steel rim back on one of the carriage wheels did.

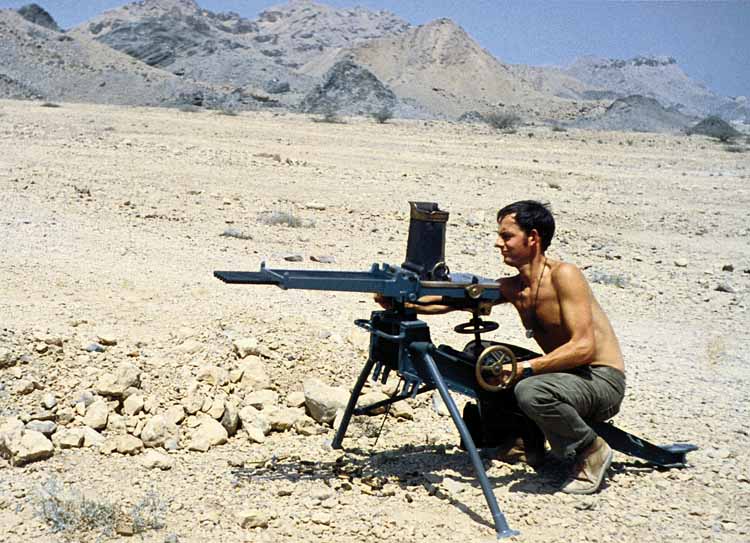

Firing the Nordenfelt

Although this machine gun was capable of firing 120 rounds per minute, we were never able to fire more than five at any one time without having to clear one or more of the breeches of an empty case. We soon understood why we should have been using solid brass case ammunition – the extractors often pulled away the base of the rolled brass case leaving an expended case stuck in the breech. It also emphasized the fact that the ammunition and the machine gun probably did not arrive in Muscat and Oman at the same time because they were not suited for each other. Possibly the ammunition accompanied a consignment of Marini-Henry rifles. Whenever a primer failed to detonate (and that was not often despite the age of the ammunition) and when the base came away as well, we were left with a potentially dangerous situation of having a live round in the breech.

Our Immediate Action for such stoppages and blockages was to push out the empty case or live round from the muzzle end of the barrel with a cleaning rod taken from one of the many mid to late 19th century small arms that we had discovered in the ‘tribal arms store’ at Bait al Falaj

In the early 70s, just after the present ruler had overthrown and replaced his father, there were many thousands of rounds of commercially made solid brass case Martini-Henry ammunition in Oman and this ammunition, together with an ornately decorated Martini-Henry rifle locally known as a “sama’a,” was still carried by the older men as a status symbol and as a right. Indeed, one of the many causes of unrest at the beginning of the 20th century was the attempt by the British government and the Sultan of the time to control the arms trade in the region. By many, this was seen as an attempt to interfere with the right to bear arms and was not a popular move. We did find solid case ammunition but, unfortunately, all the solid case ammunition we found and tried was useless leaving us with just the rolled case ammunition to use.

Our small supply of rolled case ammunition was expended all too rapidly and we never got to know the gun as well as we would have liked. It tried to tell us some of its secrets and until recently I did not realize the significance of the slight movement of the barrels between volleys. It seems that the designer put a most unusual device on models with five barrels or more – it was the Nordenfelt automatic scattering gear. Chinn says of this, “…the shots composing a volley were separated from each other by a space of three feet between each bullet. Thus volley fire of ten shots would cover respectively five to ten men in formation. The spread of bullets can be given for any distance up to five hundred yards by adjusting a thumbscrew placed on the left rear of the gun. Beyond that range it was thought that the natural dispersion of the gun would ensure sufficient spread. When firing volleys at bodies of troops, the lateral direction of the gun could be slightly altered after each discharge so that no two volleys would fall in the same target area.”

The restoration and the use of Nordenfelt No. 6024 provided us with many happy hours and experiences unavailable to the majority. In one sense, it is a shame that we did not have the correct ammunition for the gun that would have enabled us to have a more consistent firing experience. Yet, we made do with what we had and it still provided an understanding and familiarity with a historic antique weapon that represents an interesting period of history. When I left Oman in May 1972, the gun was standing guard at the right hand end of the veranda of the British Sergeants’ Mess. The gun is now an exhibit in the Sultan’s Armed Forces Museum at Bait al Falaj.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V14N2 (November 2010) |