By Robert G. Segel

The Somme Offensive took place between July 1 and November 18, 1916 in the Somme department of France on both banks of the river of the same name. The offensive occurred due to the severe losses the French were taking in the Verdun sector just east of Paris along the river Meuse since February 1916. To relieve the French, the Allied High Command decided to attack the Germans to the north of Verdun thus requiring the Germans to move some of their men away from the Verdun battlefield and move them to the north relieving the pressure on the French in Verdun. Accordingly, the first objective was to relieve the French at Verdun and the second objective was to inflict as heavy as losses possible upon the German Armies by the combined Anglo-French forces to create a rupture in the German line that could then be exploited with a decisive blow. On all counts, and in terms of human loss, it was a disaster.

The battle at the Somme started with a weeklong artillery bombardment of the German lines with over 1,738,000 shells fired at the Germans with the idea the artillery would destroy the German trenches and barbed wire placed in front of the trenches. The Germans had deep dugouts for their men and all they had to do when the bombardment started was to move these men into the relative safety of the deep dugouts. When the bombardment stopped, the Germans would then know that this would have been the signal for an infantry advance. They then moved out of their dugouts and manned their machine guns to face the British and French.

The Anglo-French soldiers advanced across a 25 mile front. George Coppard, a machine gunner at the Battle of the Somme wrote, “The next morning we gunners surveyed the dreadful scene in front of us… it became clear that the Germans always had a commanding view of No Man’s Land. (The British) attack had been brutally repulsed. Hundreds of dead were strung out like wreckage washed up to a high water-mark. Quite as many died on the enemy wire as on the ground, like fish caught in a net. They hung there in grotesque postures. Some looked as if they were praying; they died on their knees and the wire had prevented their fall. Machine gun fire had done its terrible work.”

The opening day of the battle saw the British Army suffer the worst one-day combat losses in its history, with nearly 60,000 casualties. The original relatively small British Army had been decimated in the early years of the war and in 1916 the British Army consisted of a volunteer force, “Kitchener’s Army,” and going over the top at the Somme was the first taste of battle for many of the men. As this was now a volunteer force, many battalions were comprised of men from specific local areas and these losses had a profound social impact giving the battle a lasting cultural legacy in Britain. It also had a huge social impact for the Dominion of Newfoundland, as a large percentage of the men that had volunteered to serve were lost that first day.

At the end of the battle, British and French forces had penetrated a total of six miles into German occupied territory. The appalling casualties of the British Army were 420,000 (including the nearly 60,000 on the first day alone), the French lost 200,000 men and the Germans nearly 500,000 for a total of 1.2 million men. Many found it difficult to justify the nearly 88,000 Allied men lost for every one mile gained in the advance. Truly a “Lost Generation.”

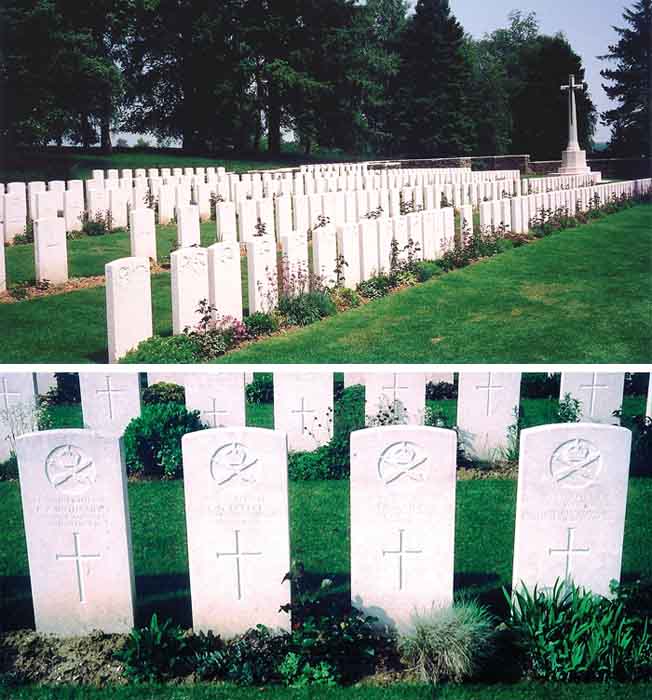

Lapugnoy Military Cemetery

Lapugnoy is a village approximately 3 miles west of Bethune and the Lapugnoy Military Cemetery is one of many such cemeteries that are common in the nearby countryside. The first burials at the Lapugnoy Military Cemetery were made in September 1915, but was most heavily used during the Battle of Arras, which began in April 1917. The dead were brought to the cemetery from casualty clearing stations, chiefly the 18th and the 23rd at Lapugnoy and Lozinghem, but between May and August 1918 the cemetery was used by fighting units. The Lapugnoy Military Cemetery contains 1,324 Commonwealth burials of the First World War with 3 being unidentified, and 11 from the Second World War, all dating from May 1940. There are 965 from the United Kingdom, 349 from Canada, 7 from Australia, 2 from South Africa and 2 from Germany.

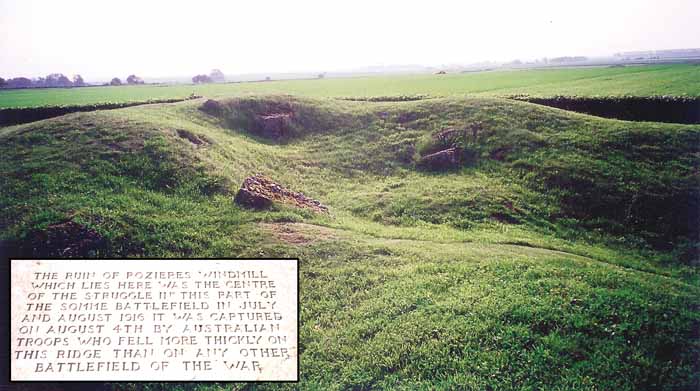

Pozieres

The village of Pozieres is located approximately 6.5 miles northwest of Albert. The Australian 1st Division attacked Pozieres early on July 23, 1916 and captured the town after fierce fighting. The Germans launched several counter attacks but were repulsed. The Germans then launched one of the heaviest artillery barrages of the war and shelled the Australians unrelentingly At the height of the bombardment, shells rained down at the rate of 20 per minute (one every 3 seconds). After three days, the 1st Division had lost 5,285 men. The Division was withdrawn and replaced by the 2nd Division. The Germans continued their attack and after 10 days, the 2nd Division was withdrawn after losing 6,848 officers and men and replaced by the 4th Division. When the 4th Division was exhausted, they were replaced by the 1st Division, who were then replaced again by the 2nd Division who were then replaced again by the 4th Division until all three Divisions were almost destroyed. More than 50% of the Australians who fought at Pozieres were killed, wounded or captured during the relentless fighting.

At the center of the Pozieres fighting was the Pozieres windmill and was the highest point of the entire Somme battlefield. The Germans had converted the ruins of the windmill into a machine gun emplacement. Two major German trench lines crossed the field in front of the windmill site and thousands of Australians were killed and wounded in the surrounding fields while attempting to capture the formidable defensive positions. After the war the windmill site was acquired by the Australian government and now stands as a memorial to the 23,000 Australian who were killed or wounded in the Pozieres battle.

Australian casualties over the whole war were 215,000 men, which as a percentage of troops in the field, was the highest of any Allied force.

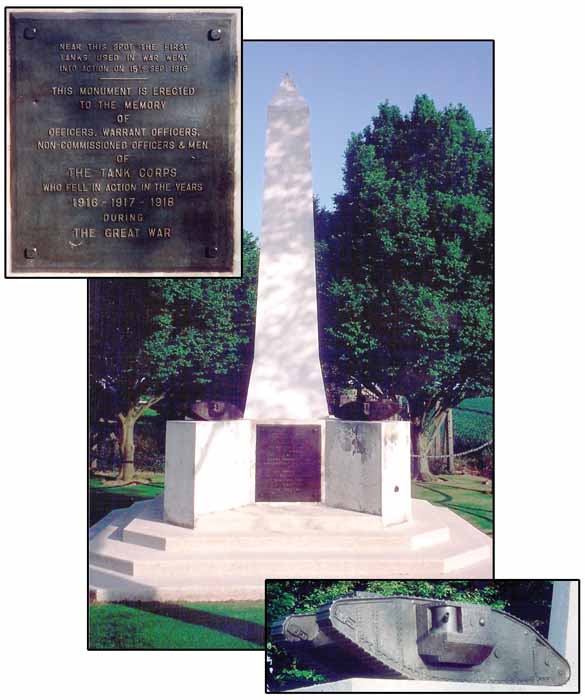

Pozieres is also the site of the Tank Monument. Ten days after the Australians left the Somme, the tank made its debut. The Battle of the Somme saw the first use of the new, mobile, armored tank. The monument to the Tank Corps has four bronze tanks at each corner.

Beaumont-Hamel

Approximately 7 miles north of Albert is the village of Beaumont-Hamel. The Newfoundland regiment as part of the British Army was assigned the section of line at Beaumont-Hamel. Although this was the Newfoundlanders first battle in France, they had seen action in Gallipoli.

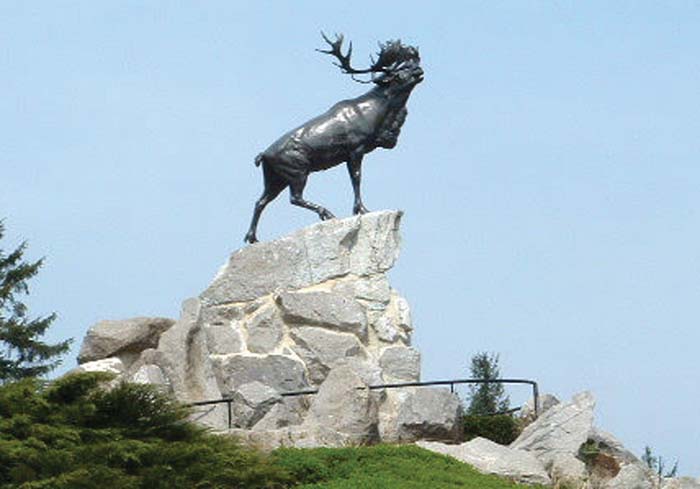

The Newfoundland Memorial at Beaumont-Hamel is one of five memorials established in France and Belgium in memory of the major actions fought by the 1st Battalion of the Newfoundland Regiment and the largest is at Beaumont-Hamel. On a mound surrounded by rock and shrubs native to Newfoundland, stands a great bronze caribou, the emblem of the Newfoundland Regiment. At the base of the mound, three bronze tablets carry the names of 820 members of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, the Newfoundland Royal Naval Reserve and the Mercantile Marines who gave their lives in World War I and have no known grave. Of the 801 New-foundlanders that left their trenches on July 1, 1916, only 69 returned to answer the roll-call. The dead numbered 255 with 386 men wounded and 91 recorded as mission.

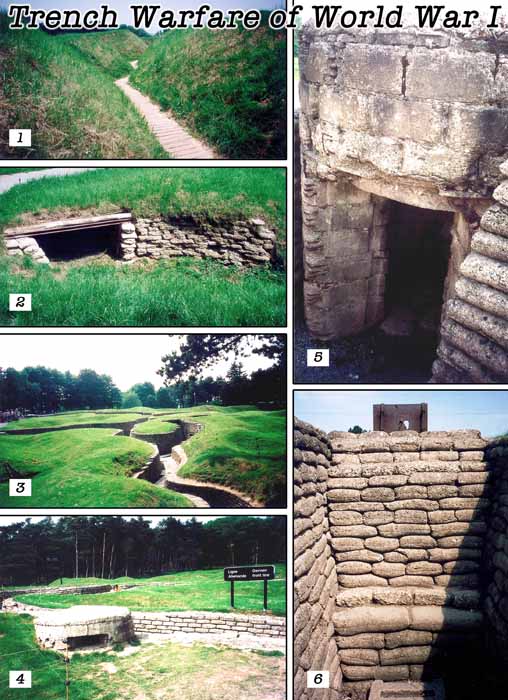

This site is one of the few in France or Belgium where a visitor can see the actual remains of trench lines of the Great War battlefield and the related terrain and a number of the trenches have been restored. However, reality is just yards away and unexploded ordnance is still in evidence with sections of the area posted as off limits and dangerous.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V13N10 (July 2010) |