By Leszek Erenfeicht

Almost twenty years before the West went PDW-crazy with advent of micro-caliber rounds that made the concept viable at last, a machine pistol was created in Poland showing all the features required from that seemingly novel class of automatic weapons. It was officially called the Pistolet maszynowy wzór 1963 (PM-63), but most people refer to it as the “Rak” (Polish for cancer). It was lightweight, compact, capable of serious firepower, yet holsterable to leave the hands free for whatever job they were needed for. When boxy just started to seem sexy, those classy, curving lines of the Rak pleased the eye of beholder.

The re-armament of armies with automatic rifles chambered for intermediate ammunition throughout the 1950s and 1960s resulted in growing marginalization of the classic pistol-caliber submachine gun. Yet, it was this very same process of warfare modernization that nearly brought it down to the brink of extinction, paradoxically, brought it up back again – although in a completely different guise. A new wave of compact submachine guns, or even machine pistols, were meant to be the self-preservation weapon for commanders, gunners, drivers, pilots and the like. Thus, a PDW-style weapon had to be devised from scratch because the level of technology available in the 1950s did not allow for the intermediate-round assault-rifle to be cut down any smaller, and the classical submachine gun was too large and bulky to fill the need. Something completely new was needed – and quick.

There was one additional problem to the East of the Iron Curtain. Wartime experience had proved that the 7.62×25 Tokarev round was too powerful to have a controllable compact submachine gun chambered for it. Additionally, despite the remarkable energy level and penetration of this round, its terminal ballistics were less than stellar. It was even worse in its handgun ammunition role. The Soviet Army, having re-armed itself from a 19th century virtually recoilless, revolver (the M1895 Nagant), they loathed the large, heavy and kicking like a mule, yet inefficient Tokarev M1933 pistol. After the war in 1951, the Soviet military went to another extreme adopting instead a small-sized, blowback Makarov pistol. It was chambered for a new round, the 9×18 “57-M-181S”, designed by Boris V. Syemin, referred to colloquially as the “Makarov round.” It was reasonably accurate and efficient at pistol distances, but way too weak to have any effect at the classical “front-line” submachine gun ranges. On the other hand, its small size and limited level of energy allowed for creation of the compact machine pistols, like the Stechkin APS. In the field, though, where obsolete tactical doctrine called for it to perform a surrealistic role of the soldier’s primary combat weapon, it was soon deemed inefficient and replaced with a folding stock AKS-47 automatic rifle.

One of the facets of the post-Stalinist “thaw” in the Eastern Bloc was the drive towards legalization and solidification of the satellite-states dependency on the USSR and, in military terms, taking shape of an alliance to counter-weigh NATO. The treaty was signed in Warsaw, Poland, in May 1955, and therefore it was called the Warsaw Pact – even though it was steered solely from Moscow and served solely Moscow’s interests. De facto, it changed the situation marginally – it was still the Soviet Union that commanded the “allied” militaries directly from Moscow, but in appearance they were now independent, national military forces – if only on paper. The Treaty allowed for a re-creation of the national façade in each member-state’s military, and loosened the up-to-then iron grip the Soviet Union had over their defense industries and armaments. At the same time the “allied” militaries were shown the hitherto top secret Kalashnikov rifle and Makarov pistol with their respective ammunition, whose appearance was met with amazement. A lot money was spent by the Czechs on their intermediate round while their new Big Brother already had such ammunition for several years. So much money was wasted to buy licenses to manufacture the “world’s most advanced” models like the M44 Mosin-Nagant carbine, the PPSh41 and PPS43 submachine guns or the TT33 pistol, while the seller knew perfectly well that they’re obsolete and even worse – that immediately after the new rounds and arms are de-classified, the “allies” would have to pay even more for another set of licenses. The growing concern over these practices made the new post-20th Party Congress Soviet leadership take an unprecedented step. As the military establishment was adamant that the 7.62×39 chambered rifle had to be the backbone of each “member-state” army, the manufacturing licenses for SKS and AK-47 were for a limited time offered at very reasonable discount prices, while in the handguns department they were left to their own devices altogether. This was a remarkable step aside from the Stalinist-era extortion-style marketing, and most Warsaw Pact states jumped upon the occasion. The neo-Stalinist Czechoslovak leaders of the era chose to literally “stick to their guns” – and became the only Warsaw Pact state to have their army completely kitted-out with domestic hardware.

Wilniewczyc Redux

Piotr Wilniewczyc, the creator of the most famous Polish small arms, the Vis wz.35 (a.k.a. the Radom) pistol and the Mors wz.39 submachine gun (SAR Vol. 8, No. 3) survived the war, and after the cessation of hostilities returned to work. His weapons designing abilities were not needed, though as the official position of the new rulers was that designing indigenous guns is pointless, as the superiority of the Soviet small arms design is prevalent. He started to teach mechanics again, at first in the Lodz Technical University, as the one in Warsaw was laid in ruins. He then returned to the capital, and while teaching the young engineers, he wrote several books that for years were the backbone of small arms designers’ education in Poland.

After 1955, the Polish small arms design school was revived; as fortunately many of the pre-war foremost designers survived both World War II and the subsequent civil war and political purges. In 1957, Wilniewczyc started the design of his first post-war semi-automatic pistol, the WiR wz.57, chambered for the 9×18 round. His design eventually lost to the competitors, the group of young military small arms experts who designed what later became the P-64 Army pistol.

While still honing his WiR wz.57 design, Mr. Wilniewczyc started to think about the compact, light automatic weapon for close-combat role, chambered for the pistol round: something along the same lines as the APS Stechkin, but from the first instant intended to be a purely self-defensive weapon, and not the primary armament. It was meant for platoon leaders, support weapon crews, airborne troops and the Ministry of Interior special services. In late 1956 and early 1957 he had already created a study of such weapon, with the grip-mounted magazine well and slide telescoping the barrel, something of a cross between a classic submachine gun and a semi-automatic pistol. It was an incarnation of the ideas developed by his former subordinate from pre-war times, Jerzy Podsendkowski, in his 1944 MCEM-2 weapon, designed in Great Britain. The MCEM-2 was an ancestor to the whole generation of the post-World War II submachine guns with grip-contained magazines and breech bolts telescoping the barrels. The Czech Holeczek submachine guns (Sa-23/25 chambered for the 9×19 and Sa-24/26 for 7.62×25) and Israeli Uzi being just two most famous of the lot.

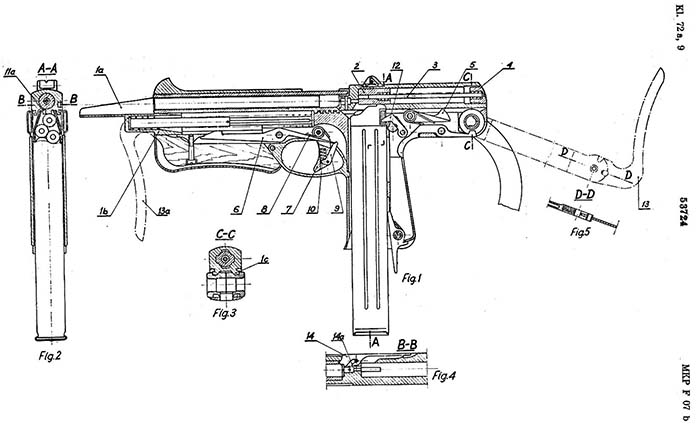

The 1957 study weapon was blowback operated and already fitted with the rate reducer. The form of that slide proved to be the most outstanding (some would even say outlandish) features of the Wilniewczyc gun. It is an outside slide, reciprocating along the rails on top of the frame just like an ordinary semiautomatic pistol, but contrary to the APS, also with an outside slide, this weapon fired from an open, and not closed bolt. The barrel, fixed yet easily replaceable, was connected to the frame by five ribs – just like in John M. Browning’s FN pocket pistols.

At that time the code-name Rak was born. Several urban legends are connected with that name; the most persistent of them making it an abbreviation from Reczny Automat Komandosów (Commando Hand-held Automatic Weapon). The late Professor Stanislaw Kochanski, close associate and pupil of Mr. Wilniewczyc, disputed the theory. The word “Automat” was used in Russia when Mr. Wilniewczyc studied small arms designing there during the WW1, and later on, up to this date (e.g. Avtomat Kalashnikova, the AK), only for automatic rifle-class designs. Mr. Wilniewczyc was a terminological purist. He time and again chastised his students and co-workers alike for such blunders, and it is highly unlikely that he would ever call his work using the wrong term, as it was chambered for the pistol round. According to Kochanski, the name Cancer could stem from two things. First, the cocked weapon was very unusually shaped for those days as it looked as if it was positioned backwards, just like the canard airplane flying the horizontal stabilizer first. In the Polish language there is an expression “chodzic rakiem”, meaning “walking backwards”, like the cancer moves. The indirect proof that the name was used as a word – and not as an acronym – is Wilniewczyc’s own joking remark from the times, where he fought an uphill struggle against the terminal illness that eventually killed him in December 1960. He is reputed to say that, “Either the cancer is going to finish me first, or I would finish the Cancer earlier,” playing on the names of his gun and his illness.

The cancer got the better of him on December 23, 1960. After his death, the Rak design team with Marian Wakalski, Grzegorz Czubak and Tadeusz Bednarski took over the whole of the design and started to improve it.

The Novel Design

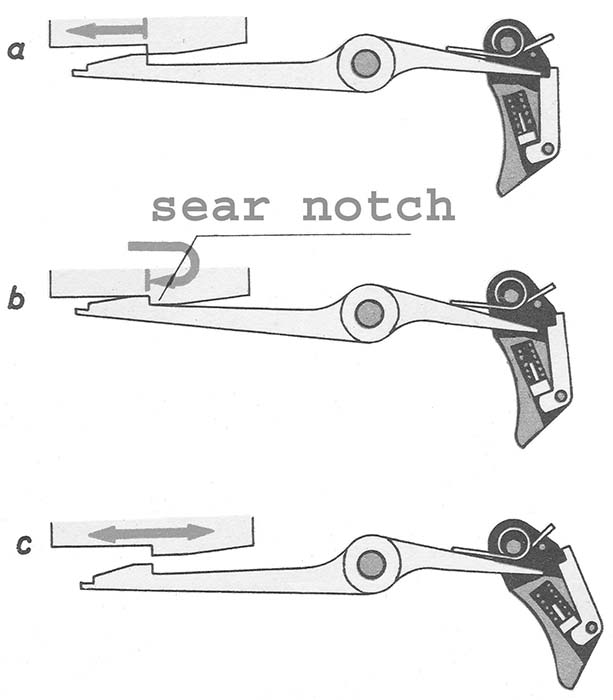

What started to emerge after a year of their work was a truly remarkable gun, with many novel and unconventional design treats. Rak was a selective fire weapon, yet the trigger had no selector lever of any kind. It fired semi-automatically when squeezed lightly and fully automatic if squeezed all the way back. This was pioneered in the Czechoslovak Sa-23/25 SMG, but the Polish design is radically different, using only the general idea. Soon, in 1969 the Austrian Steyr MPi-69 joined the dual-squeeze-selective-fire club, but the feature remained unique until in 1977 when the space-age Steyr AUG rifle made it a household idea.

The slide was still an outside-riding type, similar to the Danish M/1945 Madsen. According to Kochanski, Wilniewczyc deemed that a vital advantage of his design, making the Rak much more difficult to jam. He compared such a slide to the Roman sandal – if a pebble enters it, all the wearer has to do is shake it out and continue walking. If that pebble enters the high laced boot (or the bolt buried under bolt cover, deep inside the receiver) it takes much more time and effort to get it out. He might well be right – but on the other hand (or foot?) it is a lot harder for the pebble to enter the Boondocker than the Roman sandal.

The outside slide was provided with a muzzle jump compensator – a trough-shaped projection of the slide extending beneath the muzzle, which Polish soldiers christened the “spoon.” This spoon travels with the slide, which enables for another useful unique feature of the Rak; it can be cocked single-handedly by resting the spoon against some hard object and giving the pistol grip a shove until the slide trips the sear and remains in the cocked position. After depressing the trigger, the spoon would now travel back to battery with the slide and will be projecting under the muzzle at the moment of discharge deflecting some of the gases upward to reduce the muzzle jump.

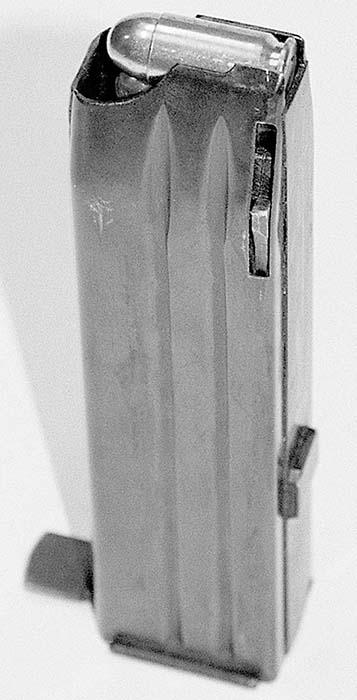

The case extraction is also somewhat unusual. The extractor is conventionally placed in the bolt face of the slide but the ejector is actually a projection of the left magazine lip, as in the Webley & Scott M1909 pistol. Wilniewczyc liked that feature and to implement it he went back to where all burp-gun designers fled from: he revived the Schmeisser staggered-row, single feed magazine. Unfortunately, this was a very bad idea combined with a cartridge as short and stubby as the 9×18. The staggered-row, double feed Stechkin magazine is way easier to fill.

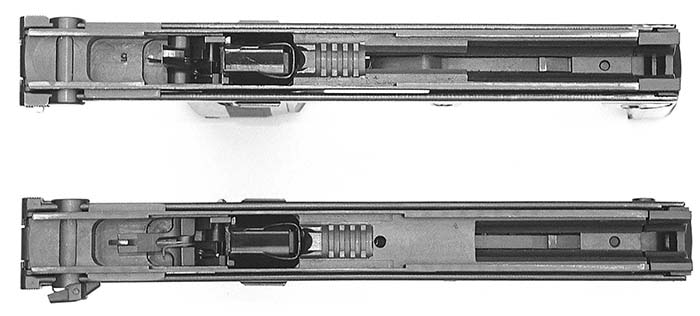

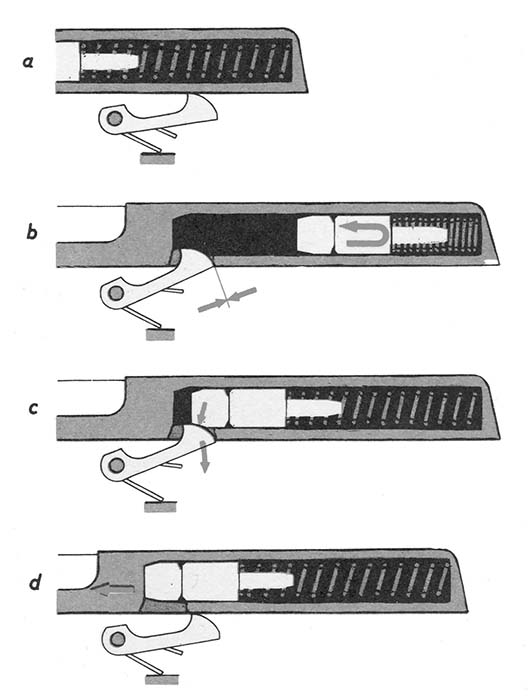

Another Rak gadget is an inertia in-line rate reducer. It retards the return of the slide in fully automatic fire to limit the rate of fire, which in a compact submachine gun is a good idea. The rate reducer consists of two parts: a weight reciprocating within the rear part of the slide, and a spring-loaded lever rising from the rear part of the frame. The weight travels back with the slide. When the slide hits the rear of the frame and rapidly decelerates, the inertia of the weight overcomes the action of the weight spring, continuing on its rearward movement. As the weight slides rearwards inside the slide, it reveals a slit in the bottom of the reducer chamber. Into that slit a spring-loaded reducer lever hook engages that holds the slide open. Then the reducer weight hits the rear end of the slide and, after a very brief interval, it’s the spring’s time to overcome the inertia of the weight eventually slamming it forward inside the reducer chamber of the slide. The conical head of the weight pushes the reducer lever hook out of engagement with the slide slit thus freeing the slide to return to battery. If the trigger is squeezed all the way, the sear remains depressed and the slide is propelled home by the return spring stripping another cartridge from the magazine, chambering it, and fires. If the trigger is squeezed just half-way, the sear is released by the disconnector and catches the slide and holds it until the trigger is released to reset the trigger mechanism.

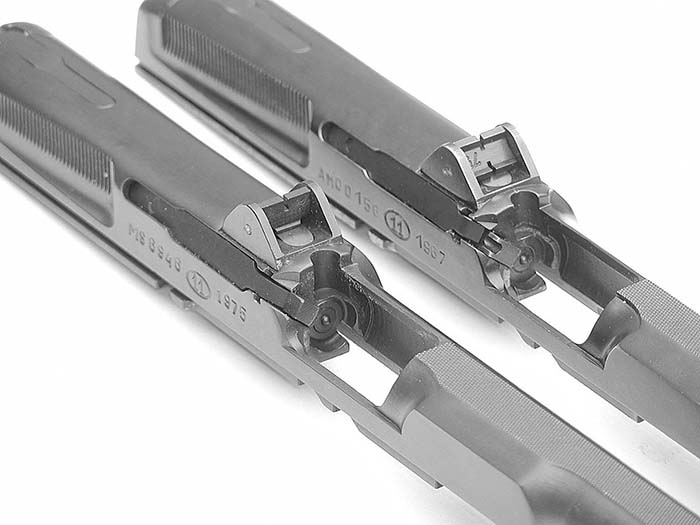

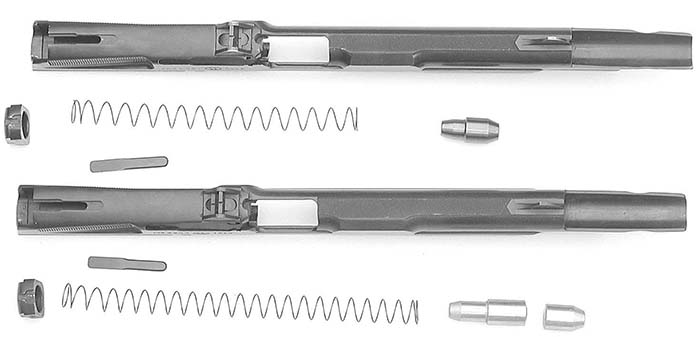

The rate reducer weight of Wilniewczyc’s original project was truly cylindrical in shape: a single piece made of tungsten – a metal much heavier, but also much more expensive, than steel. This early reducer is set on a guide rod, along which it travels, which at the same time keeps the weight’s spring. It was only known from the patent drawing and it is not sure if it was ever actually made. The later reducer weight is also single-piece affair but longer, with tapering front and rear edges, and with a rear part of somewhat smaller diameter. The guide rod was dispensed with, the reducer weight was made solid, and the spring is much wider in diameter. The narrower rear part (stem) of the weight doubles as the spring guide. Such arrangement was retained as late as early production, and all the Polish Army field manuals, technical manuals and weapon’s charts feature that type of reducer. But after only one year of production, a military review board ordered several changes, mostly to decrease the unit price of the Rak. One of these was to get rid of the tungsten weight. Instead, it was made of steel, elongated to retain the weight. Shortly afterwards it was plain that the elongated one-piece reducer weight increased the wear significantly. As of the early 1970s, all single-piece reducers were ordered to be replaced with a new, two-piece design. This was also an all-steel one, with no tungsten, and consisted of two parts, that according to the late issue technical manual, are called “reducer” (the cylindro-conical forward part) and “inertia weight” (the rest), as if they performed some different roles. The laws of physics make them both travel together and act as a single unit – but now that they are separate, the tensions developed are smaller, and the weight breaks off less frequently than the one-piece model. In its final design, the reducer slows the rate of fire from well over 1,000 rpm to 600-650 rpm.

One of the most characteristic devices of the Rak is the folding forward grip. This is a late addition, though. At first the Rak was fitted with a wooden fore end and a top-folding metal stock with a rotating, U-shaped, arched butt plate that was somewhat reminiscent of the AKS-47, but narrower. The weapon could be fired with the stock in one of the three positions:

- folded with the butt plate folded under the fore end;

- folded with butt plate extended to form a fore grip;

- unfolded for firing from the shoulder.

The butt plate doubling as a fore grip was another Czech influence, even though the Czech Sa-25/26 had a side folding butt. Firing the Rak with both hands had to be inaccurate, as the need to use the stock as the fore grip precluded using it from the shoulder. Also, such fore grip was extended in front of the muzzle, leading – it was feared – to heat, blast and occasional bullet injuries to the weak hand. That is when the compensator “spoon” was first devised – to fight the muzzle jump as much as to improve the safety of use. The compensator shielded the hand from hot gases, precluded extending fingers into the path of the bullet, and if the firer did in fact place his finger in it inadvertently, the slide would have stopped short of igniting the round. However, fitting of the compensator also precluded unfolding the stock with the slide in battery. The firer had to cock the weapon before handling the stock which called for sweeping his hand in front of the muzzle of the cocked machine pistol. This was intolerable for obvious safety reasons.

Nevertheless, in January 1962, the design was sent to the Radom plant, then called the “General Walter” Metal Works, for further development and prototype work. There, in late 1963 and early 1964, a prototype batch of 20 weapons was manufactured; already with a completely redesigned stock. The top-folder gave way to the extendable butt stock with two machined flat stock bars connected by a small rotating sheet metal butt plate. As the new stock precluded using the butt plate as a fore grip, the fore end was also redesigned. It was then made of plastic, and part of the fore end was hinged to form a folding fore grip. That design feature can be traced to the Mauser 1957 prototype submachine gun. Now that the weak hand holding the fore grip was safely tucked under the fore end, the Rak could be fired with both hands holding the grips with the stock resting on the shoulder, which improved the accuracy in burst fire by enhancing control over the gun. The new stock and fore end were designed by two designers from Radom; Ryszard Chelmicki and Ernest Durasiewicz, who were given a Polish patent for it in October, 1972. One cannot help seeing something familiar when observing the ultra-modern HK MP7 with a folding fore grip of almost identical shape and purpose.

The price to pay for all these novelty features was a somewhat shaky and less user-friendly stock and fore end. It was found perfectly acceptable in a PDW-class firearm for second-line soldiers in the 1960s and 70s, when the marksmanship training for such users was tepid enough not to show the deficiencies of the new design. The attrition rate of firearms used in special units was high enough to cover them up, as well. If you got a bunch of snake-eaters tough enough to break a Kalashnikov rifle, then they’re poised to destroy any weapon in the world anyway. Nonetheless, to the objective eye, the fore grip and stock really did possess some design flaws. The flimsy, loosely-hinged butt plate was utterly useless for any purpose – intended or otherwise. It was designed with only one objective in mind: to fit snugly under the rear of the frame while folded. For that reason the plate was but a 2 inch long strip of flat thin metal that was too short and too flimsy to matter. To obtain that all-important flush fit under the frame, one had to rotate it through 270 degrees every time it was deployed or folded, which meant there were no butt plate catch or retainer to keep it open. Many special units of both military and police simply duck-taped it open spoiling the only purpose it ever served efficiently. They also soon developed the practice making the folding fore grip useless. They mostly fired the Rak with fore grip folded, because the hinge was weak and the fore grip soon developed an unacceptable degree of play.

The concept of the PDW-class weapon called for a compact, holsterable weapon. The size and weight of the folded Rak were ideal for that, but initially only the long, 25-round magazines were meant for it. This forced the user to carry the weapon empty – or else the long magazine sticking out from the grip would make his service life, especially the withdrawing, a nightmare. Thus, the next Radom implemented improvement was the creation of a shorter 15-round “holster” magazine, which could be kept inside the grip of the holstered Rak, to give the soldier a chance to fire off those most important first shots straight after the drawing of the weapon.

The first prototype batch of 1964 had all the plastic parts machined rather than molded. The moulds were too expensive to risk making them before the final shape of the stocks was sealed. On the left side of the slide, under the sight, all were decorated with an etched Polish Eagle, which was a clear reference to the pre-war tradition of Polish Eagle marked receivers and slides of Radom made firearms. The powers-that-be were not amused, though, and Radom was ordered that no other weapons be decorated that way.

After the military acceptance testing program was finished, the Rak was officially accepted into the inventory of the Polish Army as the “9mm pistolet maszynowy wzór 1963 (PM-63)”. In 1964, the Radom plant started to prepare for production.

PM-63

Mass production started in 1967, though, and it was only in the latter 1960s that the first new PDWs made their way into the hands of the Polish soldiers, soon becoming the regulation side-arm of tank crews, scouts, RPG gunners, ATG missile-crews and drivers. Soon the down-sides of the small machine pistol started to show, which gave rise to many, not always grounded, accusations leveled at the Rak. Some of these stemmed from the novelty of the design and the lack of experience on the part of the designers. Some were ironed out during the production run such as the twice redesigned magazine catch that eliminated the inadvertent dropping-out of the magazine, while the redesigned stock bars catch facilitated the deployment of the stock. Not all of the users were happy with these changes: the magazine catch, eventually buried into the grip plates, was now hard to release while shooting in gloves. Other problems were rooted in the lack of knowledge and disregard for gun-safety and/or gun exploitation rules. Many reducer levers were damaged during re-assembly, if the reducer lever was not positioned properly prior to re-attaching the slide. In late production Raks, a special bracket was added to eliminate the lever over-travel, which cured the problem completely.

Other design changes were aimed at reduction of the unit price. Already discussed was the all-steel reducer weight replacing the tungsten one, but the changes also included redesign of the frame to replace the deep-drilling of the return spring channel with just milling a groove for it. The chrome plated-all-over barrel of the first Raks was replaced with a blued one, retaining only the chrome plated bore and chamber. The captive recoil spring unit, consisting of a two-piece telescoping spring rod with end pieces holding the spring that enabled the return unit to be detached as one piece, was replaced by a simple spring and one piece short rod.

Two types of special replacement barrels were devised for the PM-63. One was a blank-firing drill barrel meant for troop training and movie industry use. On the outside, the blank barrel was identical to the real one, but the bore was constricted to enable the weapon to cycle fully automatically when firing blanks. It was designed by Marian Gryszkiewicz and Ryszard Chelmicki of the Radom factory, who were given a patent for it in 1978.

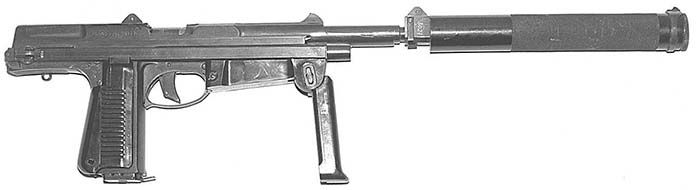

The other special purpose replacement barrel was the silenced version for the special forces. The barrel was made longer, sturdier, and the part extending forward of the slide’s spoon was threaded to accept an all-metal sound suppressor designed by Marian Gryszkiewicz (this project was code-named “Safloryt”). As the suppressor casing obscured the sights, the suppressor was fitted with its own set of sights, placed on top of the casing. As the “Makarov round” develops a sub-sonic muzzle-velocity, standard ammunition could be used for the suppressed version. No hard data is available as to how many of these were ever manufactured.

The PM-63 was exported in the early 1970s by the Cenzin Foreign Trade Office. It was at Cenzin’s instigation that a prototype 9×19 variant, called the PM-70, was designed in 1971. To accommodate for the new, more conical-cased ammunition of the significantly higher muzzle velocity and energy level, a heavier .55 kilogram slide had to replace the old model, with corresponding changes to the grip area and magazine. Despite the initial concern, the prototype was shooting well from the very start, and while the recoil was significantly higher, mechanically it fared surprisingly well. Nevertheless, Cenzin didn’t follow through on their marketing strategy and only one batch of 20 PM-70 Raks chambered for the 9mm Luger were ever manufactured.

All in all, within the decade of Rak production between 1967 and 1977, approximately 70,000 basic variant PM-63 PDW-class machine pistols were manufactured.

The Rak Heritage

For four decades the PM-63 Rak was a tool of trade for Polish Army soldiers, and never had to be tested in real combat by the original owner. Some of its critics would add here “fortunately,” which unfortunately, is true. Without a doubt, it was a remarkable achievement of the Polish designing and manufacturing capabilities, as the only (except Skorpion) Eastern Bloc burp-gun ever to be manufactured in a sizeable quantity and serving in front-line units of the major Warsaw Pact army. On the other hand, it is a weapon that added her own, inimitable, sins to the long inventory of the blowback burp-guns’ deficiencies. The wobbly useless butt plate, the breaking off fore grip and exposed magazine catch were already mentioned. But the most controversial feature of the PM-63 is arguably her exposed slide-style breechblock. Scores of urban legends surrounded it, while still serving in the Army. Not a single instance of eye-ball crushing contributed to that slide was ever corroborated, even though sporadically gas mask oculars were indeed scratched or even broken. The sights reciprocating with the slide proved no big deal in reality, too. After all, the Rak was not designed for sniping. It is a war time ultimate defense machine pistol: more of a saturation “spray and pray” area weapon. The first shot is more or less aimed, where the rest happen to hit is a matter of recoil, muzzle jump and physical strength of the shooter. Her accuracy was enough for self-defense, and the military users praised her as a handy, compact, well-balanced gun. A shooter unable to score at least Marksman with her was a rarity. On the other hand, Rak was practically useless – or could even be dangerous – for Police SWAT work, as a precision weapon for physical elimination of an armed and dangerous individual on a busy street. Nevertheless, back in the Communist days, where real submachine guns like the HK MP 5 were just something seen on TV, these were in fact used by SWAT teams of the Polish Police, and still can be seen carried by bank guards. Railway Police (SOK) also uses them, and recently there was a botched hold-up in Warsaw, in December 2004, when a railway cop opened up with his Rak wounding one of the would-be robbers.

The unusual design and appealing shape of the PM-63 triggered much interest in the world. Although no foreign army ever officially adopted it as a standard-issue military weapon, some Communist police forces did. Many of these were bought by the former East German People’s Police, where they were called the “klein-Maschinenpistole PM-63” and issued to the DDR SWAT teams (BV, Bereitschaft Volkspolizei) and to the anti-terror units. Some of these survived the fall of the Berlin Wall and even served for a while with the police of the Free State of Saxony in the re-unified Germany, along with the Polish-built helicopters. Smaller quantities of the Raks were imported by other ComBloc countries, like Cuba or Vietnam.

The latter export resulted in a copy-cat version manufactured in China. During the Sino-Vietnamese war of 1979, the Chinese captured some of the PM-63s used by the Vietnamese tank crewmen. The Chinese were just on the look-out for a compact machine pistol for their Special Forces and Police, and so the state-owned Norinco Works copied the Rak and started a limited production of the Type 82 machine pistol. This weapon is known in two variations, differing in sights arrangement. One of these was an attempt at lengthening of the Rak’s sight radius by relocating the rear sight to the rear extreme of the slide. The other has sights identical to the Polish version. Both are copy-cat versions of the early production Rak, with old-style butt catch and exposed magazine catch. The Chinese Rak was also fitted with a second, front, sling eyelet, which points to the fact, that it was devised as a principal weapon, slung across the chest, and not to be holstered. The Rak copy had lost internal Chinese competition to the Schnellfeuer-style Type 85 machine pistol, but nevertheless, the Type 82 was frequently exhibited at the international arms fairs of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

As with all other Communist compact machine pistols, the Rak was frequently used as an urban guerilla weapon by the leftist terrorists of the 1970s. The PM-63 had the dubious distinction of being featured in several high-profile cases. It was probably the East German channel through which the Rak reached the Red Army Faction in Germany. On September 5, 1977, the PM-63 was used during the Hanns-Martin Schleyer kidnapping. In the 1970s it was frequently seen on TV, in the hands of various Palestinian factions roaming Beirut. This was probably the source of the Rak found by the SAS Pagoda Troop storming the Iranian Embassy at the Princess Gate in London, hijacked by the anti-Khomeini Iranian dissidents in 1980. Footage from Panama, taken prior to Operation Just Cause in 1990, show some of the General Noriega irregular “supporters” armed with PM-63s and shooting them towards the crowd of the anti-Noriega protesters. As late as the 1990s, the PLO leader, Yasser Arafat, was photographed with a holstered PM-63 within reach on his desk.

The PM-63 was also used with tragic effect in Poland. On December 17, 1981, shortly after Martial Law was imposed, at the Wujek coal mine the Katowice riot police SWAT team armed with Raks shot 17 miners protesting against the Communist rules.

Shortly thereafter a new compact submachine gun was designed, to replace the ageing Rak. The Glauberyt Project led by the Radom Plant designers, culminated in the new PM-84, with enclosed bolt, but still chambered for the 9×18. Despite apparent success, it was never mass-produced. At that time the 9×19 Luger ammunition was introduced into the Army and Police, and the thoroughly redesigned PM-84 was accepted as the PM-84P. But that’s quite another story…

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V9N11 (August 2006) |