By Rob Krott

I was standing with Oyay Deng Ajak to the left front of a 12.7mm (.51 caliber) DsHk heavy machinegun, mounted atop the highest boulder on the hilltop. I’d already snapped a photo of the weapon and was digging out my notebook to jot down the arsenal info when: Ka Bam! From the enemy position opposite us an incoming round from another 12.7mm HMG streaked over my head. Fortunately, the gun had jammed, sending only one solitary round my way. I jumped down behind the rocks and we all had a nervous little laugh. The Government of Sudan (GoS) Army had once again taken a pot shot at me.

That happened during my first visit with the SPLA (Sudanese People’s Liberation Army) in 1994, a six month sojourn in various guerrilla camps throughout the southern Sudan, where I had an opportunity to observe SPLA combat operations. I recently returned for another visit (April 1998) hoping to see my old friend, Commander Ajak, now the SPLA assistant chief-of-staff. The war in Sudan is between the predominantly Muslim, Arabic-speaking north and Christian and animist black Africans in the south. The southern population is about 3 million (minus those killed off in combat and by famine) and provides the base of support for the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army. There has been a “Civil war” since independence over 38 years ago. The SPLA is just the latest (and most successful) guerrilla movement since Sudan gained independence, January 1, 1956.

A wide range of small arms have been pressed into service by the southern Sudanese guerrillas, who I consider to be very well equipped insurgents. I don’t know whether to call them the rag-tag conventional army of “New Sudan” or a well organized, well equipped guerrilla force with heavy weapons support. The workhorse of that heavy weapons support is the 12.7mm DShK 1938/46 heavy machinegun. The Degtyarev 12.7mm boasts performance similar to the Browning .50 caliber HMG. A versatile weapon, it has been used throughout the world by the Soviets, their allies and third world guerrillas in a variety of roles: anti-aircraft, ground support, crew-served infantry, vehicle mounted, and co-axial armored vehicle armament. The DShK 12.7mm can be operated from its wheeled mount or its AA tripod. A simple weapon to operate, it loads and fires the same as an RP-46 7.62mm machinegun.

At one SPLA 12.7mm HMG position I was given the honor of loading belts as the gunner opened up on a combined attack by Sudanese Army troops and National Islamic Front (NIF) mujahideen. The replying 12.7mm and 14.5mm machinegun fire and some distinctive ripping from a dozen or so “obsolete” Soviet RPD 7.62mm light machine guns from the enemy derogatively known as jellaba (slavers) was intense.

Another 12.7mm heavy which I witnessed in action was the PRC Type W-85, the only one I’ve ever physically seen. The Type W-85 has a long legged tripod convertible to ground support or anti-aircraft roles, weighs only 40.78 pounds, and fires a left hand fed 60 round belt. The example I saw was missing its optical sight, but the skeletal shoulder stock was in place.

The 14.5mm KPV anti-aircraft machinegun mounted as a single (ZPU-1) barreled ground support weapon is formidable. Several of these were lugged up the rock-strewn Sendiru Hills and used against the mujahideen’s human wave attacks. I also observed both ZPU-2 and ZPU-4 weapons in action.

The Goryunov’s SGMB 7.62x54Rmm (one if six versions of Pytor Maximovich Goryunov’s design) was seen throughout the south Sudan emplaced on its wheeled mount. The Goryunov, largely replaced by the PK series in most arsenals, is easily identified even at a distance by its longitudinally fluted barrel. While the 7.62×54 rimmed cartridge dates back to 1891, making it the world’s oldest standard military cartridge, its rimmed case often causes some problems with feeding in modern automatic weapons. It was favored by many of the famous Russian designers and it has been in use so long by the Russians that it would probably be a costly and massive re-tooling effort to switch production to another .30 caliber machinegun cartridge. The Russians have produced improved versions of the cartridge: the high-penetration 7N13 is used in machineguns. An armor piercing round, it will penetrate 10mm steel plate at 400 meters. The 7N14 is a sniper cartridge built for the SVD rifle and manufactured to higher standards for accuracy.

Kalashnikov The Genius

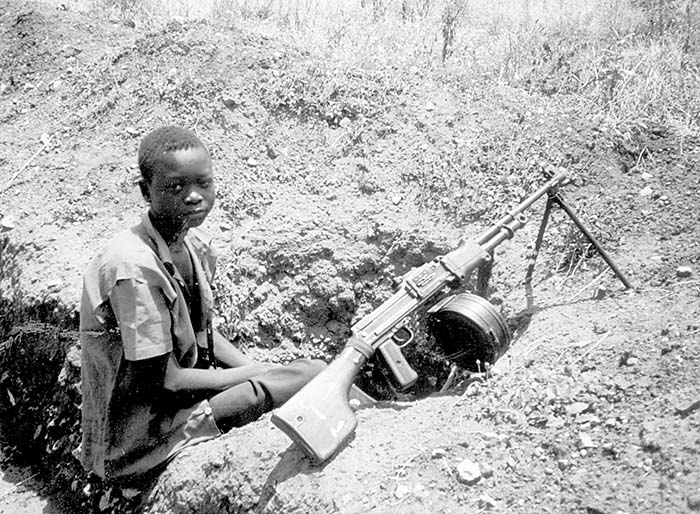

Of course the most commonly used SPLA infantry weapon is the Soviet Kalashnikov assault rifle or one of its many variations – a good weapon for guerrilla troops, easy to operate, easy to maintain, and reliable under harsh field conditions. Many of the SPLA troops are relatively young, some barely 12 or 13 years old. Pre-teen and adolescent boys comprise a large number of the SPLA forces and an even larger percentage of their trained, but unarmed reserves. Given its relatively short length (34.25”), the Kalashnikov is well suited for troops that are small in stature. I discussed this with an SPLA caption. Our conversation went something like this;

Captain – “Yes, even our twelve year old boys can carry an AK-47. This man, Kalashnikov, he was a genius”.

Krott – “Not was… is.”

Captain – “What?”

Krott – “I mean he’s still alive.”

Captain – “No!”

Krott – “Yes, Mikhail Timofeyevich Kalashnikov, the weapons designer and inventor of the AK-47 is still alive. I know someone who met him a few years ago.”

Captain – “No. Are you sure, Rob?”

Krott – “Positive. He’s still alive. He was a young sergeant at the end of WWII, so he’s probably in his seventies now.”

Captain – “A genius, the man is a genius.”

The captain walked away, marveling that his hero, Kalashnikov, was still alive.

Hand-carved Stocks

I had the opportunity to carry a Kalashnikov at times. Though the German in me prefers an MpiKS72 with its side folding wire stock, the weapon I usually carried was a Hungarian AMD, the short barreled variation of the AKM, easily identified by its large muzzle brake, plastic foregrip, and ventilated metal forend. I like the AMD, even though the muzzle flash is a little high profile. I carried three different AMDs, one of which was missing the original flash suppressor. Guerrilla weapons are quite commonly chopped up and cobbled together. It’s not uncommon to see hand carved stocks and forends replacing damaged furniture, duct tape and wire holding forends or stocks to barrels, and sheet metal, rivets, and wire mending broken wood stocks. Though in the southern Sudan weapons in a poor state of repair are usually carried by local tribesman rather than front-line fighters. The guerrilla war here has resulted in the local tribesmen obtaining modern firearms. In some instances, their rifle is the most technologically advanced possession these primitive herders own. One Kalashnikov I saw was carried by a Taposa tribesman. His only other piece of kit was a blanket draped casually about his shoulders as he wandered about nude.

While I normally wore a bit more in the way of clothing, on one occasion I grabbed “my Kalasshnikov”, borrowed from Oyay and moved forward with two guerrillas for a look-see at some nearby NIF positions. As I came down from the SPLA outpost something caught my eye. Glinting in the harsh African sun I found some 7.62mm NATO rounds with Arabic headstamps lying in piles by the remains of dead mjuahideen. Probably left over after pockets were emptied and equipment and uniforms stripped from the bodies – most SPLA guerrillas wear “captured” uniforms (well laundered and with the bullet holes patched)) – but, the G-3 rounds were not scavenged by the guerrillas. I surmised they must have ample supplies of 7.62 x 51mm/.308 NATO for their few captured G-3s. Still, good insurgency logistics would insure everything of value, even a few loose rounds, was salvaged from the battlefield. During Mengistu’s regime in Ethiopia, the SPLA was well supplied with weapons and munitions including IMI (Israeli Military Industries) UZI 9mm sub-machineguns (a few of which I observed in the hands of SPLA reconnaissance troops). With Menigistu’s ouster other “friendly African nations” have stepped in to fill the void. I encountered a trash pit full of cases of discarded 7.62x54R ammunition. Discarded because it was all blank training ammunition. I guess some one screwed up when they were loading the trucks.

As for the captured G-3s fielded by the SPLA, upon inspection they all bore Islamic arsenal markings leading me to believe their origin was probably Saudi Arabian licensed production, though it’s possible they were Turkish, Pakistani, or Iranian. Most of the G-3s I saw were carried by local tribesmen or “militia”, the SPLA preferring to standardize their rifle ammunition solely to 7.62x39mm. At the time I wished dearly for a tactical sniping scope, mount, bipod, and box of Lake City .308 match rounds. The G-3s have a lineage stretching back through the Spanish CETME to the SIG 45 (M) which first introduced the delayed blowback with roller bearings, punches out these 7.62 NATO rounds at 2625 fps. While not my first choice for a tactical medium range sniping weapon due to its heavy, slack filled trigger-pull and many other flaws as a battle rifle, in the accuracy department it was head and shoulders above any other rifle I encountered save for a few rusting WWII era bolt guns. Tuned up in the field to resemble a G3-STG/1 police sniper with bipod, set trigger, and something approximating the Schmidt and Bender scope, it would do a good job.

Various Machineguns

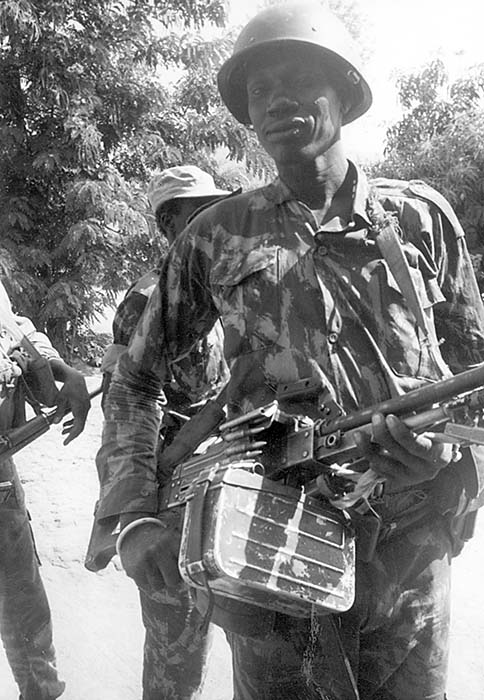

While visiting the guerrilla base at Chukudum in Eastern Equatoria, Commander Pieng Deng Cual allowed me to troop the line under the watchful eye of 1Lt Alier Riek Jok. I noted some interesting weapons: 1Lt Jok carried a Hungarian AKM and I saw a few Czech model 58 assault rifles which the troops call a “She”- pronouncing the Czech factory stamp on the receiver. There were few heavy machineguns, just the odd 12.7mm Russian Dshk on a vehicle mount. Light machineguns were mostly RPKs, RPDs, a few PKMs and the odd MG3 GPMG courtesy of Saudi Arabia (probably, as the arsenal stamp was a wreathed lion with sword) via the Sudanese Army. The Rheinmettal MG3, the updated MG42 chambered for 7.62 NATO, is one of the finest machineguns in the world. Since my first visit to the Sudan, I had the opportunity to see many of them in action in Bosnia. It’s also a popular weapon with both the Turk and Iranian armies which may account for the Islamic regime in Khartoum having significant numbers of them.

A weapon I couldn’t readily identify at the time, a battered light machinegun sporting a Bren type top feed magazine with an overly long Kalashnikov type selector switch. I’ve discussed with Peter Kokalis and we surmise it must be a rare Czechoslovak Model 52/57 LMG chambered for the M43 7.62x39mm cartridge (the Model 52 LMG was originally chambered for the arcane Czechoslovak 7.62mm Model 52 /7.62x45mm cartridge).

One of the most interesting small arms I inspected was an old WWII era Soviet RP-46 7.62x54Rmm light machinegun. The RP-46 is basically a Degtyarev DPM modernized by Shilin, Polyakov, and Dubinin to fire from a belt feed. The RP-46 uses a 250 round metallic belt (the same used with the 7.62mm Goryunov heavy machinegun) or a Degtyarev flat drum after the top cover is changed. Called the “company machinegun” by the Soviets it was considered, at nearly 28 pounds, a medium machinegun.

The two light machineguns I encountered most frequently were RPDs and PKMs. The RPD (Rushnoi Pulemet Degtyarev), though now considered obsolete, can still be found fielded throughout the third world, especially in Africa. A dependable and combat proven weapon (in the past it was used with great affect – and admiration – by SEALs in Vietnam and Selous Scouts in Rhodesia) it still remains a fixture in many special operations unit armories worldwide. The RPD loads two fifty round metal belts (of 7.62x39mm ammo) which are snapped together before loading into the RPD’s metal drum magazine. It’s an easy weapon to operate though it necessitates a special wrench for proper adjustment of the gas cylinder. The RPK (Rushnoi Pulemet Kalashnikova), a heavy barreled bipod equipped AKM, replaced the RPD as the Soviet squad automatic weapon . Something I’ve never agreed with as the RPK, while streamlining ammunition and parts logistics at the small unit level and simplifying weapons training, is less than auspicious as a squad or platoon level weapon. It lacks a quick-change barrel and can not be used for sustained automatic fire. It must also be fired using pre-loaded 75 round drums, making ammunition re-supply in the heat of battle problematic.

The PKM, a medium or general purpose machinegun, is chambered for the workhorse 7.62x54R cartridge. The introduction of another caliber infantry weapon into any military organization complicates ammunition logistics, but more so in a guerrilla army which may have extreme difficulties in procuring adequate stocks of ammunition. The PKMs I saw with the SPLA rarely had an extra box of ammo available. The PK (Pulemet Kalashnikova) replaced the RP-46 “company machinegun” (numbers of which are still fielded by the SPLA) and the 7.62 SGM battalion-level machinegun in the Soviet Army. Kalashnikov not only mimics his AK operating system in the PK (the PKM is an improved, lightened version), he literally turned it upside down and added an innovative feed mechanism. The weapon incorporates Kalashnikov’s rotating bolt, the Czech Vz52 belt drive, Goryunov’s quick-change barrel and cartridge feed mechanism, and the DP trigger. At nearly twenty pounds the PK is technically a GPMG, but is commonly utilized as a light machinegun. I briefly carried a PKM on patrol in the Sudan in 1994 and grew to appreciate its many features, least of which was that it weighed about five pounds less than the M60 I carried as an 18-year-old infantry PFC.

Bolt Guns

While in Chukudum a truckload of “militia” loaded up for a trip north. I refer to them as militia as they obviously weren’t rank and file SPLA but were armed. Dressed mostly in civilian clothes, they were armed with a motley collection of bolt action and semi-automatic rifles with the odd battered Kalashnikov thrown in. Immediately recognizable was a .303in Rifle, Short Magazine, Lee-Enfield Mark III. The SMLE, in the hands of trained rifleman, is one helluva weapon and is considered by some to be the finest bolt-action combat rifle ever fielded (though I’m sure many an Old-Breed Marine would disagree…). In many parts of the southern Sudan such a weapon could be put to good use as a tactical sniping weapon – solely with its open sights. The simple blade foresight combined with the rear sight leaf graduated to 2,000 meters would allow a good shot to engage targets well in excess of a Kalashnikov’s maximum effective range. Another bolt-action carried by these militia, the Mosin-Nagant 7.62mm M1944 carbine was an archaic weapon even in WWII. Basically the same rifle as the 1938 type except with the addition of the folding cruciform bayonet, I also saw Chinese models (copied by them in 1953) of the Mosin-Nagant M38 and M44 Carbine (7.62x54R). Seeing widespread use in a variety of climes and conflicts since its introduction during WWII despite being based on an 1891 design (obsolete since the First World War) these carbines are still dependable man-stoppers with 7.62 x 54 rimmed cartridge. A definite improvement over the Russian M91 rifle of which I also saw a few examples. I’d have preferred to hunt eland for the soup pot, but I shot at several baboons with an M44. Some of the militia were also armed with SKS carbines, a weapon I often saw in the hands of local herdsmen.

I kept my eye out for American weapons, hoping to see an M-1 Garand or an M-2 carbine, and really wishing for an M-16 (yeah, I know maybe not the best battle rifle ever, but I’m comfortable with it ) but to no avail. Not in this part of Africa. What I was really looking for was an AR-10, the Armalite .308 NATO rifle, as a small lot of these weapons was sold to Sudan by Interarms. No such luck.

In 1944 Oyay Deng Ajak’s light infantry – heavily equipped with RPD light machineguns, a few RPG-7s, and at least one venerable 106mm recoilless rifle – along with Oyay’s only armor, two captured T-55 tanks, held a blocking position south of Juba in Sendiru Hills. With the tides of war four years later there was another blocking position nearby at Mile Forty (forty miles from Yei on the way to Juba) just the other side of the Nile. This was commanded by one of Oyay’s subordinate commanders, Assistant Commander Abraham Wana Yoane, 2nd Brigade, 2nd Region, who told me that Iraq is supplying weapons to Khartoum. This was obvious by the markings on much of the captured ammunition. Last year (9 March 1997) the SPLA unleashed “Operation Thunderbolt,” its big southern offensive, capturing several key towns and capturing thousands of small arms including a hundred or more light and medium machineguns from GoS forces. More importantly, large quantities of equipment – several T-55 tanks, anti-aircraft guns, artillery – and large stocks of North Korean, Chinese and Iraqi ammunition for 12.7mm DShk machineguns, 14.5mm ZPU anti-aircraft guns, 107mm multiple rocket launchers (MRL), PKM machineguns and RPD machineguns fell in the bag. Despite this, any weapon which will still launch bullets, no matter how old or how arcane, is still pressed into service. One of my escorts on the road to Mile Forty was armed with a well-maintained Sterling MK II 9mm sub-machinegun (the “Patchett”). The Sterling was also fielded as a semi-automatic, the Police Carbine Mark 4. The Sterling probably ended up in East Africa as part of a police equipment package. The Sudan was a British colony until 1955 so it’s quite possible the weapon had belonged to some British constable.

Commander Yoane’s heavy weapons included truck mounted 107mm multiple rocket launchers, T-55 tanks, several ZSU 23-2 23mm anti-aircraft guns (in the infantry support direct fire role), a couple of B-10 82mm and B-11 106mm recoiless rifles, and a 37mm AA gun which nearly sent me diving for cover when it cut loose during my inspection tour. Additionally there was a generous distribution of RPD light machineguns, PKM machineguns, the ubiquitous RPGs carried by anyone who didn’t mind the extra weight, and various mortars, including 60mm hand-held tubes.

Weapons Employment and Basic Load

A good example of how the SPLA fields its weapons and equips its troops is the defense of Bunio in 1992. During the dry season (winter) of 1992 the GoS army launched its offensive on Pibor. From Pibor the GoS Army was able to move several battalions of infantry and over a hundred vehicles south, attacking and capturing Kapoeta, the regional capital. GoS army forces, bled out by their assault on Kapoeta, were unable to continue offensive operations until a month later when they attacked Bunio, a small abandoned bush village. Bunio’s defenders, the SPLA’s Eastern Equatoria Military Command’s 1st Battalion withdrew in disarray and without orders. The brigade commander, Commander Salva, ordered the battalion back to Bunio. GoS Army forces had withdrawn, abandoning the jungle outpost, to consolidate and strengthen their hold on Kapoeta. On 15 August Salva ordered his 2d Battalion commanded by Assistant Commander (Major) Peter Panyang Daniel, 37, to Bunio to replace the unreliable 1st Battalion. Daniel’s battalion occupied a perimeter defense at Bunio. He deployed four companies of light infantry (actually very lightly equipped guerrillas, many without shoes and uniforms) and a headquarters and weapons company. His “battalion” numbered on 412 men.

Armed with Kalashnikovs each infantryman carried a basic load of 120 rounds. Grenades were in limited supply and consisted mostly of Russian RGD-5 and Chinese stick type grenades captured from GoS Army troops during the fighting in Kapoeta. There were nineteen light machineguns on the perimeter, several RPDs, PKMs, and solitary Bren gun and a Degtyarev RP-46. There was one Goryunov SG43 7.62mm heavy machinegun dismounted from an armor vehicle. RPD gunners were issued 800 rounds each. Basic loads for the other light machineguns differed though none had more than 800 rounds available. Daniel’s battalion, later reinforced by additional heavy weapons makeshift-mounted on Toyota’s, prevailed against a much larger force of attacking GoS Army supported by tanks and artillery.

Weapons aren’t everything, especially in the southern Sudan- where a weapon may be anything.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V2N6 (March 1999) |