Nearly as famous as Alcatraz, a few miles north overlooking the bay, the tower rises. Along with the imposing walls behind, its presence dominates the landscape with a fearsome reputation every bit as keen as its water-bound cousin and San Quentin remains very much in business today, an icon of the California state prison system. Beginning construction in 1852, the original “dungeon” stands preserved as the first publicly funded building in the state. California’s first land-based facility, labor was supplied from a prison ship that had been the common method of incarceration. San Quentin serves as home to America’s largest Death Row. From 1893 through 1937, 215 hangings took place here. Its famous gas chamber saw 196 men breathe their last, and 11 more since the conversion to lethal injection after 1995. San Quentin has been the site of all state executions since 1938, while legal objections continue to challenge the changing methods employed.

Hollywood first featured San Quentin in a film of the same name, starring Humphrey Bogart in 1937, when Alcatraz was merely beginning life as a civilian Federal prison. The tales of hard times at San Quentin are equally harsh and, while only partly surrounded by the Bay’s chilling waters, a series of machine gun towers served to ward off any notions of escape in a time before fences were erected to contain the prison population.

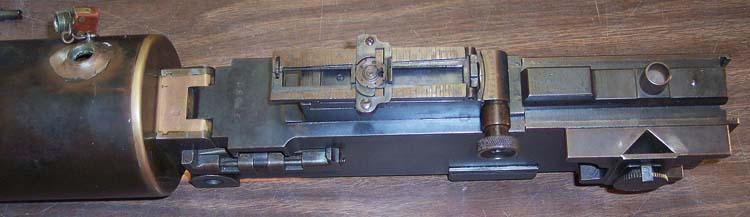

Among the pieces of hardware in those towers over the most part of the 20th century were a number of Browning Model of 1917 water cooled machine guns. The finest such weapon of World War I, the .30 caliber 1917 was introduced late in the war and saw action in Europe only briefly. Both praised for its reliability and suffering from the effects of rushed manufacture, the Browning soon established itself as the foundation for all manner of machine guns in U.S. military service. While the venerable water cooled was being manufactured for immediate delivery, John M. Browning was hard at work at the Colt’s factory developing an air cooled version for use in tanks (adopted as the Model of 1919) as the Great War wound down. Roughly 70,000 1917s were assembled within a few months after the war’s end, reduced from orders for 100,000. With many going into long term storage, some were also released for other uses, prison duty being among them.

The Browning 1917s served well in the prison system for many years, holding sway over the grounds and poised to mow down any prisoner who might dare to look for the exit. No such stories have surfaced, and the Brownings apparently were never fired in anger and, in time, they were retired from duty. All but one of the San Quentin 1917s were sold in the civilian market years ago. The last was installed under glass in the prison museum, where it languished as a symbol of an era long passed.

Fast forward a few decades. An upcoming visitation of VIPs to San Quentin prompted the suggestion that the old war horse Browning be activated for a live fire demonstration. The staff armorers were excited about bringing the 1917 out of mothballs, but one obstacle remained: there was no one on the staff who had operational familiarity with the historical machine gun. Also, the state of California would not budget any funds for this effort, so any assistance, and even the ammunition, would have to be donated. Rick Shab, of BMG Parts Co., Inc. was contacted and asked to help find someone, proficient in the mechanics and function of Browning belt fed machine gun, to volunteer their service to the state of California for a hard day’s work. This author soon got wind that this dire sacrifice was needed, and felt compelled to answer the call. This was accomplished expeditiously, before anyone else could get in line first and rob him of the fun… that is, need unnecessarily suffer the hardships of this noble, but difficult, duty. Rick soon found himself volunteered to contribute his expertise as well. This offer of service was accepted and the arrangements were made.

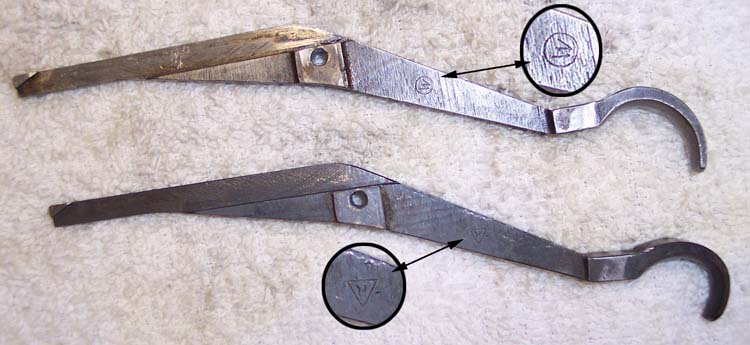

On a typically overcast day in June, Sgt. Gabe Walters and Officer Sung Kim, from the armory staff, had the Browning 1917 set out on a table at the range facility, located across the main road from the prison itself. After introductions and a few moments sharing our common fascination with this wonderful piece of history, the first lessons of function and field stripping of the gun began. Sgt. Walters and Officer Kim were enthusiastic and anxious to learn. They insisted on doing the thorough cleaning, oiling and preparation of the gun, happy to get their hands dirty. Tasked with simply explaining, teaching and observing as they gained the experience they needed, care was also taken to study the manufacturer markings on the various components. This rare opportunity for a hands-on study of a piece of WWI history was not to be missed.

This particular 1917 was made by the New England Westinghouse Company of East Springfield, Massachusetts, a division of Westinghouse Electric, opened in 1915 to manufacture the Mosin Nagant rifles for Czarist Russia. Production of the 1917 at N.E. Westinghouse totaled over 48,000 guns, and the San Quentin Browning would have been assembled within days of the close of hostilities. Nearly half were assembled in the months after. The other major manufacturer of the Model of 1917 was Remington Arms Co, Bridgeport Connecticut, with some 19,600 units. While John Browning was present at Colt’s, and the Hartford gun maker had the manufacturing rights, they were producing several other models already and did not have capacity for the quantities required. Thus, Colt’s had no choice but to contract with its competition and produced only 2,500 Model 1917s in house.

While plenty of spare parts were brought along just in case, it turned out that the gun had a good supply of parts stock kept with it. All were of correct vintage, which tends to confirm that this Browning was in original condition when acquired, and that the spares came with it at the time. The only change this gun had seen since World War I was the addition of the reinforcing stirrup to the breech lock area of the receiver. This standard upgrade was, essentially, a band-aid solution to the problem of cracking that plagued the side and bottom plates of the production guns. Minor changes were soon adopted in aircraft gun manufacture to cure the defect, but as the 1917 water cooled guns were all done by that time, the stirrup was the most effective and economical treatment.

Many of the extra components had the Remington mark, though most all the parts in the gun showed the famous W in a circle Westinghouse mark. Worth noting is that these World War I manufacturers stamped their code on far more individual parts as compared with most of the later Browning producers of the World War II period. That makes it far more challenging when collecting parts for an early gun project or restoration. Some Westinghouse and Remington components are surprisingly common, while others are as easy to find as your average needle in a field full of haystacks. As for 1917 parts made by Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Co, the author has yet to find a single example: definitely in the hens’ tooth category.

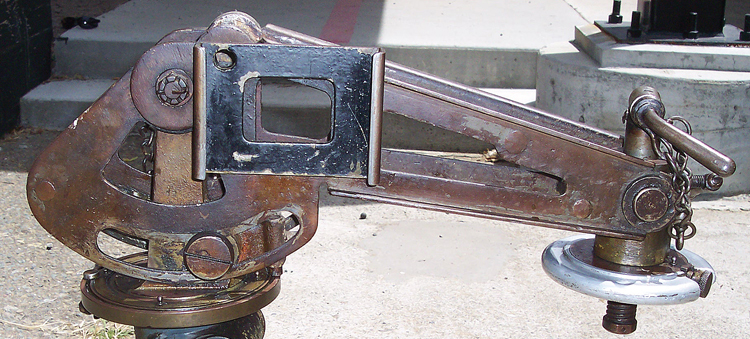

After a thorough examination of the gun, cleaning and reassembly, the only question mark that arose was regarding the top cover extractor spring. The working surface of this leaf spring was a bit on the flat side. Note was made of this and a spare was kept handy. This proved a good idea, as was confirmed upon proceeding to the firing line for the next step in our training session. The Browning was placed on its original 1917 tripod, which was in excellent condition from the cradle to about 2/3s of the way down the legs. It was there that tragedy had befallen, at least from a collector’s point of view. In order to fit in the tower fixture, the feet had been cut off, leaving the impression of an unfortunate amputation. This is the rarest of Browning .30 caliber mounts, so it was sad to see that it had been so… um… modified. But hey, it’s a prison gun and for our purposes this day, the tripod served well, all adjustments still working and looking great for her age.

At this time, we were joined by the Range Sergeant, Dwayne Meredith. With 1,000 rounds of Lake City and Greek HXP ammo belted and ready, headspacing procedures were practiced, the timing checked and the armorers introduced the belt to the feedway and charged the gun. Everything was set, but they insisted the author take the initial burst. After pretending to argue just a little, the first live rounds in several decades were soon heading downrange. The Browning sang, as though she had been pining for this stage ever since being stuffed like a pheasant under glass. Partway into the first 250-round cloth belt, there was one failure to extract from the belt. This is just what might be expected from the aforementioned flat cover extractor spring. The spare was installed and firing resumed, with everyone taking turns at the trigger. That one round was the only malfunction of the day. The old Westinghouse had just one bit of dust to cough out, from its long confinement, before it resumed making the music it was made for more than 90 years ago.

When all the ammo was spent, the smiles and good moods were still going strong. It was impossible to tell who felt more like kids in the proverbial candy store, the Browning aficionados who came to share their expertise or the guards who were getting to resurrect a relic from their museum. All were enjoying the revival of this classic and rare machine gun. In truth, there was no reason to expect anything but success, especially once the fine condition of the 1917 was known. Still, it was a magical few moments of fun.

Now, to follow up with the museum guys about that Colt 1921 Thompson hanging on the museum wall…

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V14N8 (May 2011) |