By Lynndon Schooler

The bloodiest conflict in human history brought unthinkable hardships and suffering to the Soviet peoples. The Eastern front of World War II, forever known as “The Great Patriotic War,” instilled a horrific lesson. Victory can be won with tragic heroism and sacrifice, but ultimately without technical and tactical innovation, it is a cruel waste of life. This lesson was already being learned partly through WWII and in command style and tactical abilities—the Red Army in 1945 was a far cry from the Red Army of 1941. Nonetheless, the war’s atrocities and the shock and awe of fighting a technologically and tactically superior force still haunt the region to this day. New developments were still needed in every aspect of modern warfighting, including small arms design, to offset loss of life in future conflicts and to prepare the Soviet Union for emerging threats in the new atomic age.

When Hitler’s fascist forces invaded the USSR in June 1941, the largest invasion in history, patriots came from all walks of life to do their part in answering the call to defend their motherland. One such patriot was a peasant from Kurya, in the Altai Krai region of Western Siberia. Born on November 10, 1919, Mikhail Timofeyevich Kalashnikov had a particular mechanical aptitude and was conscripted as a tanker into the Red Army in 1938. With the peace broken in 1941, Kalashnikov’s direct action was limited as a tank mechanic, but he was quickly elevated to command a T-34 tank in the following months.

In October 1941, Kalashnikov’s company came in contact with the flank of a German line near the Bryansk, a small town, as part of a greater Soviet counter offensive to slow the charge of the German Army Group Center’s blitz toward Moscow. Suddenly, his tank was struck with a loud blast, and a ringing echo shrieked in his ears paired with a dizzying flash of bright light. He fell unconscious, shell shocked and with lacerations from shrapnel across his body. His body was recovered from the knocked-out tank and transported east toward a field hospital.

“In the hospital, I seemed to re-live everything that happened during the months of my participation in the fighting. Again and again, I returned to the tragic days of getting out of that environment. The dead comrades rose before my eyes. At night, in a dream, automatic machine guns often occurred, and I woke up. There was silence in the ward, interrupted only by the groans of the wounded. I lay with my eyes open and thought: why do we have so few automatic weapons in our army, easy, quick-fire, trouble-free?” – Mikhail Kalashnikov

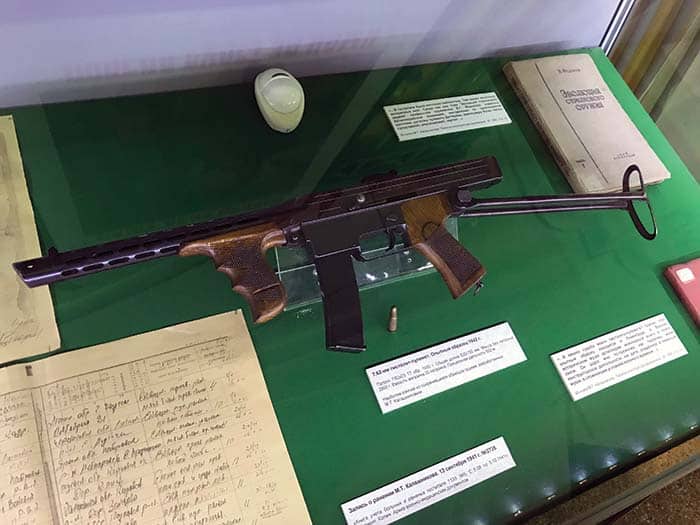

Motivated by a burning sense of purpose to equip Soviet soldiers with better firepower, he started designing small arms in 1942, once recovered from his wounds. In three months, working from a railway shop in Kazakhstan, he produced the PPK (pistolet-pulemyot Kalashnikova—machine pistol of Kalashnikov) as his first production sample, and in 1942 he submitted his design to a government trial. Although it did not progress, his skills as a weapons designer caught the eye of Soviet authorities, and they saw to it that he was placed where his talent would be demanded. Though never developed past prototype phase, by 1944 Kalashnikov had designed two self-loading carbines and a support machine gun.

In 1942-1943 the Red Army came in contact with a new German Machine Carbine, known as the MKb42h (H-Haenel/Schmeiiser), firing a unique 7.92×33 Kurz (short) intermediate cartridge. In the Eastern front, Germany was testing the weapon in small batches and later fielded the MP-43, an improved design off feedback from the test reports. Following the MKb42h were the MP-43/1, 43, & 44 (machine pistol) and final iteration, the Sturmgewehr StG44; although changes from the MP to the StG series (a name change requiring Hitler’s approval) were only minor, such as barrel diameter and a stock design.

By 1943-1944 the MP and Sturmgewehr were in limited use due to production shortfalls. Germany equipped entire units with the rifle, rather than spreading several rifles to many units across the army. Combat reports from test units noted the drastic improvement in firepower over the K98k, reduced reload time, increased ease of firing while moving and increased range over the only comparable shoulder-fired automatic arms, the MP-38/MP-40 submachine guns. This gave the Germans an edge in highly mobile warfare across urban environments.

The first examples of the German automatic carbine MKb42h and ammunition were reported to have been captured near the Leningrad region in 1942. They were sent in secret to the Soviet Army small arms proving range at Shurovo outside Moscow for testing and evaluation. The results of the testing surpassed all Soviet expectations, and after studying captured 7.92×33 in 1942-1943 the Soviet Union requested their own intermediate cartridge.

Shortly thereafter, the Soviet high command requested its own intermediate cartridge comparable to the 7.92×33. In 1943, engineers produced 7.62×41, the first Soviet intermediate cartridge. It was adopted the same year as the M43 and entered production in March 1944.

The Soviet Union began work on assault rifles capable of using the new intermediate round as early as November 1943. The research and development group was quickly issued an official state request to produce a rifle in the M43 round for the upcoming 1944 trials for a new general purpose service rifle. Designers Tokarev, Korovin, Degtyarev, Shpagin, Sudayev, Simonov, Aleksandrovich, Ivanov, Prilutsky all submitted designs for the new “Avtomat.”

Alexei Sudayev, designer of the famed PPS-43, led the initial competition with the AS-44 prototype. In 1944, the AS-44 (Avtomat Sudaeva) satisfied the specified tactical and technical requirements of the trials. A small batch was order at the Tula Arms Factory for further military testing in 1945 as part of state mandate (GAU No. 3131-45) to field a new assault rifle in the M43 caliber. Alexei Sudayev died in August 1946, and development of his prototype was halted.

The M43 intermediate cartridge was updated in 1946 at the Ulyanovsk machine building plant with a shorter casing by 2mm. The round was also modified from a flat backed lead core projectile to a boat tailed steel core projectile. The new 7.62×39 retained the M43 designation.

In 1946, a second competition was launched with updated tactical and technical requirements (TTT) of the 1945 GAU No. 3131-45, and interested designers had to adjust their prototypes for the new caliber.

In October 1946, after reviewing design sketches of 16 present entries, the commission narrowed selection down to 10 designs, including Kalashnikov’s work, and requested revised drafts. That same month, the Ministry of Armaments of the USSR sent Kalashnikov to the Kovrov weapons plant to make his prototype with the assistance of a design team.

Kalashnikov’s first sample was the AK-46 No.1 with help from the Kovrov team. The AK-46 No.1 is a select fire, short-stroke, gas-operated system. The fire control group consisted of a safety lever and a separate semi- and full-auto selector lever on the left side of the receiver. More noticeable features are the left side charging handle and receiver construction. The receiver was manufactured in two sections, a lower and upper receiver very similar to the StG. The upper portion was removable via two non-captive pivot pins just rearward of the magwell and a pin securing the pieces together held at the upper rear of the receiver. The AK-46 had a small dust cover rearward of the bolt, and the bolt carrier charging handle was on the left side of the carrier. The bolt design carried over from his earlier semi-auto carbine from 1944.

In December 1946 the first round of tests commenced, conducted at the NIPSVO (scientific and test range of shooting and mortar weapons) with 5 samples of Rukavishnikov, Korobov, Bulkin, Dementyev and Kalashnikov rifles. By May 1947, new samples of the Kalashnikov assault rifle, named AK-46 No. 2 with fixed stock and AK-46 No. 3 with an under-folder stock were produced at the Kovrov factory. The AK-46 no.2 was the second iteration of Kalashnikov’s prototype. The upper receiver and lower receiver were redesigned. The upper receiver did away with the short removable dust cover, closing the excessive openings to eliminate ingress of foreign debris. An ejection port was added on the right side as well as a left-side charging handle with a cover tightening up openings for dirt to get in to the receiver. The upper receiver also had a magwell extension. The bolt did away with a directly attached charging handle; instead the upper has an attached left-side charging handle attached to a track with an arm that engages the bolt carrier. The lower safety and separate mode selector were made more ergonomic, making it easier to manipulate compared to the No.1 AK-46.

The AK-46 No. 2 was tested in August 1947 against Sudayev’s AS-44, Shpagin’s PPSh 41 and the StG44 as comparative controls. At the time, the AK-46 was not showing signs of promise. Kalashnikov along with the design team at Kovrov were redesigning the entire weapon both in construction and operation, borrowing ideas from his rival, Bulkin, to create a new prototype. Design aspects included gas piston/bolt carrier, recoil spring assembly, a long receiver dust cover, a rear trunnion attached using three rivets and possibly a modified selector/safety from the AS-44. By November 1947, the first three samples of Kalashnikov’s new design were made at the Kovrov factory, known under the factory index KB-P-580 and closely resembling what we know today as the AK. Final testing knocked out Bulkin’s and Dementyev’s prototypes, leaving Kalashnikov ultimately the last contender in the competition. Kalashnikov’s rifle also did not meet the requirements for full-auto accuracy but was chosen due to improving promise overall and was recommended for production.

In January 1948, the Kalashnikov assault rifle development package was sent to the Izhevsk plant along with the designer himself for initial production, changing the city forever. Early AKs struggled with full-auto accuracy, not meeting the standards of the competition, so work was done to improve the production model’s accuracy without delaying the production date. There were a total of 228 changes to the design and another 214 changes to ease manufacturing for serial production. Serial production of the AK was finally mastered at the Izhevsk plant in early 1949, updating the manufacturing facility and processes to manufacture the new weapon. The Izhevsk machine-building plant’s priority was to develop the weapon with the simplest design, but with the most modern production techniques. The High Soviet Minister of the USSR finally adopted the “7.62-mm Kalashnikov assault rifle” on June 18, 1949—the work of many engineers, designers and gunsmiths over years of development, in the form of what is commonly called the Type 1

This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V22N10 (December 2018)