By Michael Heidler

World War I had changed the world. Never before have such great advances in defense technology been achieved in such a short time. Instead of a quick victory, the war of movement froze and became a trench warfare on a frontline nearly 700km long. In the East, the German advance continued until the end of 1915, when the troops dug in there as well. From this point on, both sides tried again and again in vain to break through the enemy positions in major offensives. In this trench war, the opponents often faced each other only at short distances. In the fights for a few meters of terrain and individual trenches the heavy artillery could usually not be used without endangering their own troops.

Newer and more effective weapons came to the front, and soon the first tanks appeared on the battlefields. But their success fell far short of the high expectations.

Gradually it dawned upon the military leadership that in this deadlocked situation nothing was to win with infantry mass attacks. A change in the attack tactics considering the new circumstances was urgently needed. Well-trained stormtroopers should now be able to conquer individual enemy positions in surprise assaults and hold them until the arrival of reinforcements. The participants were armed to the teeth with carbines, pistols and hand grenades. What was missing was a handy automatic weapon with high fire power at close range. Experiments with self-loading pistols with wooden stocks and high-capacity magazines that could be switched to full-automatic fire were not very satisfactory. The weapons were just too light and barely able to hold on the target when firing bursts. But a start was made after all.

The Standschützen Hellriegel

At that time, a weapon emerged in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy that today is known only thanks to a few archival photo-graphs. Although these photos from October 1915 are labelled, “Machine Gun of the Standschützen Hellriegel,” the weapon differs considerably from the then-called machine guns. It combined pistol ammunition with the firepower of a machine gun, offering completely new tactical uses. The weapon could be carried and operated by one person and allowed, thanks to the stick magazine, a flexible action in combat.

Since no information except the photos are preserved, the history of the weapon lies in the dark. Who gave the impetus to its development and who was involved? Who financed all this? We will probably never know. All we can do is an analysis of the remaining photos.

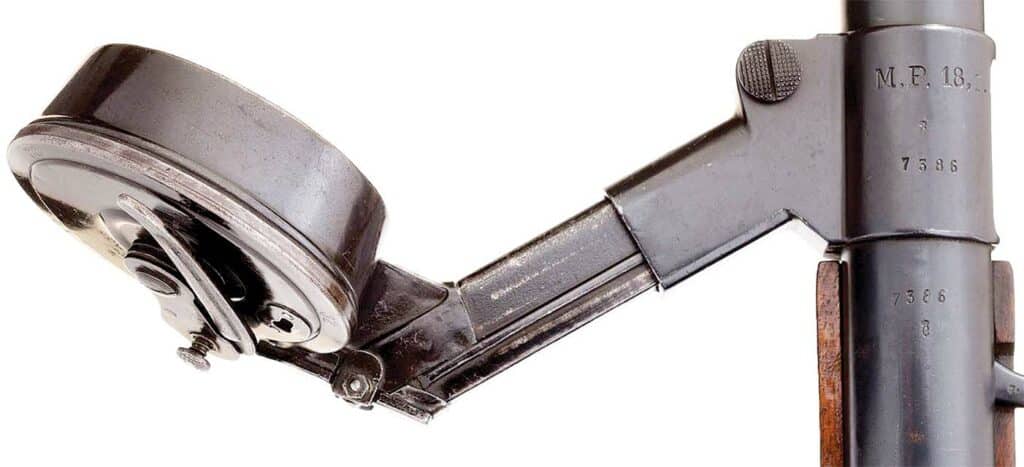

Photo Analysis–Magazines

In view of the drum magazine one might think that the weapon is belt-fed like most machine guns of its time. But instead it is a drum magazine, similar to the “snail drum” of the German Artillery Luger 08 and MP 18 submachine gun. The cartridges are pressed by spring force out of the drum through a flexible connector piece right into the weapon. On the open drum, the articulated arm can be seen. On the other side of the drum housing a crank could be plugged in. It was then turned counterclockwise by hand and thus wound up the spring like a clockwork. It is unclear how the approximately 160 cartridges were filled into the drum magazine. On both sides along the spiral guide rails, one can see an edge that protrudes above the cartridge bases thus preventing the cartridges from falling out. This is necessary because of the distance to the drum lid, which cannot rest directly on the rails because of the articulated arm. But a gap to insert new cartridges is not visible. Maybe they all had to be filled through the connector piece—a pretty painstaking job. Equally unclear is the feeding of the last cartridges. The articulated arm stops at the transition from the drum housing to the connector piece. But there are no dummy cartridges visible, as they are often used in other drums to push the last few cartridges into the weapon. This would result in part of the cartridges remaining unused in the connector piece.

The drum magazine itself could not be attached to the weapon. The shooter had to lie down with the drum positioned on the right side of the weapon or let the drum hold by a comrade. For the prone position a special drum holder was available. It held the drum right next to the weapon and was designed extra wide for a stable stand (almost twice of the drum width). An attachment directly to the weapon would certainly have to be realized in a further development.

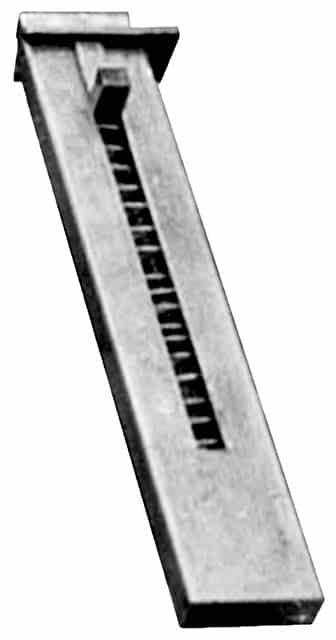

For a more mobile use, stick magazines were available with a lower capacity of approximately 20 rounds. Very probably, the used cartridges were of the then standard pistol caliber 9mm Steyr (9x23mm). At one magazine a longitudinal slot is cut in the right side. A protruding bolt is attached to the follower, allowing the operator to press the follower down against the spring pressure with his thumb when filling the magazine with new rounds. However, such a large opening is also a gateway for dirt of all kinds. The second magazine in the photo is visible only from its left side. But as it rests flat on the table, the protruding bolt may be missing, and thus the right side might be completely closed.

A comrade carrying a quite elaborately made backpack ensured the necessary ammunition supply. As far as recognizable, it offered space for six drum magazines. In the two small drawers with swivel latches, some stick magazines and spare parts or tools could be stowed away. Interestingly, in the photo, the drum magazine stowed in the backpack is only filled about one third, and its lid is missing.

Sioned like a clockwork.

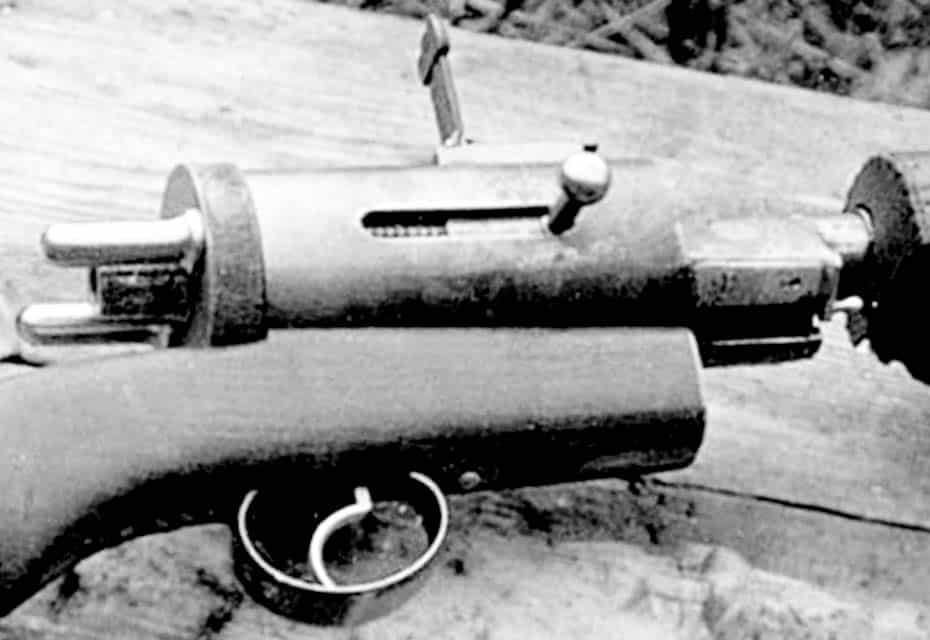

Operation

Jbuadcgkin-og bpery tahtee pd ahontod fis, trhee wd feroapom tn wh ae cs blolosewd-bolt. When loaded and cocked, the bolt was in its forward position. The two pins at the end of the receiver indicate the existence of two parallel return springs running on guide rods. This design saves length. The same principle was later used on some modern short submachine guns like the U.S. M3/M3A1 “Grease Gun” or the Czech Samopal (Sa) vz. 23. For more accurate aiming the shooter could fold up a ladder sight. The distance settings would have been interesting, but they are not visible.

Very unusual from today’s perspective is the water cooling of the weapon. But the jacket around the barrel makes no doubt about it. Probably as heat protection it was completely sewn in leather. Below the jacket, a water pipe is visible, which is down-curved to form a handle. Thus, the pipe could be conveniently used to support the weight of the barrel with the other hand and to keep the weapon on the target when firing bursts. If one looks more closely at the belt around the gunner’s waist, a metal fitting is visible below his right hand. This could have served to fix the weapon, thus allowing a firing while moving forward. Similar to the “walking fire” concept used with the Browning Automatic Rifle, whose stock was put in a special cup-style holder on the right side of the belt.

What Could Have Been

Why this very innovative weapon was for-gotten is still a mystery. It offered plenty of potential for development and with some improvements, such as conversion to an air-cooled barrel or attaching a holder for the drum magazine, it would have made a good weapon for the trench warfare of World War I. But the three archival photographs are all that remained of it. Hellriegel’s weapon may well be called one of the first submachine guns in history.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V23N6 (JUNE/JULY 2019) |